The Istanbul Modern : Hayat ve Hakikat Dream and Reality Modern and Contemporary Women Artists from Turkey

The exhibition “Dream and Reality” at the Istanbul Modern Museum provides an overview of modern and contemporary women artists from Turkey. Since women constitute many of the leading artists in Turkey, the exhibition is a valuable survey of modern and contemporary art beginning in the early twentieth century and continuing to the present.

Jointly curated by Levent Çalikoğlu Chief Curator at the Istanbul Modern, Fatmagül Berktay, Zeynep Inankur and Burcu Pelvanoğlul, the exhibition offers an opportunity to look at an important chapter of contemporary art history.

The title of the exhibition is based on the title of a novel co authored by Fatma Aliye and Ahmet Mithat. But Fatma was initially identified on the cover only as “a woman.” Fatma was also the author of an 1891 essay on Muslim Women (Nisvan-ı Islam) defending women’s rights. Although women in the late Ottoman era ( note mainly urban, upper class women)were actively promoting women’s rights, this famous first female novelist (the novel was a “Western” genre and new to Turkish writers at this point) was unnamed on the cover of the book. The position of women in the late 19th and early 20th, right before the Republic, is important to pinpoint as privileged freedom within the limitations of traditional Ottoman customs and Sharia law. ( read Reina Lewis Rethinking Orientalism for one account of some of these negotiations.)

Educational reform in the Ottoman society led to a demand for the rights of women. The first essay in the excellent catalog for this exhibition by Fatmagül Berktay outlines the relationships of women and society in the Ottoman era and early Republic. They published magazines and newspapers, and participated in meetings and charity organizations. There were by the end of the nineteenth century 40 women’s magazines and 300 books that examined the relationships of men and women. They also began to struggle for their rights. After 1908 “they began to force the limits of Sharia law and go out into the public space, to expand the means of education and to earn the right to work in the public sector, in short to bring down the walls that separated them from society.” ( p. 33) A University of Women was opened in 1914; a School of Fine Arts for Girls in the same year, although the first art school for girls had opened as early as 1864. Men and women studied together by 1921 even before the founding the Turkish Republic.

An interesting omission from the new catalog that appears in the pioneering exhibition by Tomur Atagök Cumhuriyet’ten günümüze kadın sanatçılar (Women Artists from the Republic to the Present Day) (1993) as part of the Women in Anatolia Series in honor of the 75th anniversary of the Republic, is that women’s equality in modern Turkey can be traced back much further to the nomadic cultures of Anatolia. More specifically, as Atagök summarizes women “played a central role in economic life in rural Anatolia” and produced much of the embroidery, dressmaking, carpet weaving and other handcrafts. (p.12) The tradition of sequestering women during the Ottoman years actually was an inheritance of Byzantine culture. But the “new woman” of the early Republic was still part of an oppressive, patriarchal society.

Today, as one country after another in the Middle East is throwing over dictators, the spread of Islamist ideas is rapid. Knowing how women resisted Sharia in Turkey at the turn of the twentieth century might be of use today as the new Libyan government immediately declared that it wants to institute Sharia, and Iraq has stepped back to the dark ages in its treatment of women. Afghanistan women outside Kabul are still wearing burkas as we saw in the PBS series Women, War and Peace .

“Hayal ve Hakikat” begins with benchmark historical artists, among whom the most famous is Mihri Müşfık,(1886-1950?) the first significant women oil painter in Turkey (oil painting, like the novel, was a “western” import, see Orhan Pamuk’s My Name is Red) . In the painting Mihri Hanim documents her assertive attitude, as well as her negotiation with the rules of the veil. Her dark veil is completely transparent. Mihri Hanım together with Müfide Kadri (1890 – 1912) led the way for women as part of the artistic culture of the late Ottoman society. There is a detailed discussion in the catalog by Burcu Pelvanoğlu of these early years. Many of Mihri’s students became prominent professional artists such as Fahrelnissa Zeid and her sister, Aliye Berger included in both the exhibition of women artists and in the main display in the Istanbul Modern. Sadly Mihri Hanim herself died in poverty far from home.

Hale Asaf, Mihri Hanim’s niece is also a major figure in the early period. More modernist, and cubist, she represents the next era of oil painting in Turkey. But the really spectacular painting in this exhibition from the mid twentieth century is by Aliye Burger, Sun Rising, 1954 that embraces expressionist colors in a stunningly near abstract composition.

Jumping to the late twentieth century, Canan Beykal honors Mihri Hanim in her piece Mihri Hanim’s Column,1993 a small doll sculpture that reinvokes the artists self portrait in three dimensions. It inhabits the gallery, imbuing the present with the past.

Tomur Atagök’s own painting and installations are an important connection from the latetwentieth century to the present. In the work in this exhibition, Plastic Paradise, or Don’t Soil,(1987) ( see beginning of blog) she works on steel panels with an expressionist style dominated by shades of pink and red. Her theme at this time was the contradictions of society for women: as the women on the right are enjoying themselves, a man with a knife threatens them. But her work also addresses environmental concerns about the planet in both the title and the suggestion of the empty landscape on the left. Atagök mixes popular culture with expressionist references to political events.

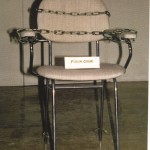

Füsun Onur also spans the late twentieth century to the present with spare conceptual art that is both playful and full of threat, as in Untitled, 1993, a chained up chair with her name on the seat. The chair is a symbol of power, property and social status ( catalog p. 130), she undercuts their function with the chain ( or in other works soft gauzy fabrics).

Nur Kocak has used a pop art aesthetic paired with photo realism to make searing comments on some of the ironies of women’s position in Turkish society. In this work she is addressing the impact of fame on Turkey’s first female director Cahide Sonku during the 1930s.

A few pioneering artists began to show conceptual art in the late 1970s. Starting in the 1980s and particularly in the 1990s, the Turkish contemporary art scene has flourished. Of the 74 artists in the exhibition, 50 of them are still active, born in every decade of the twentieth century from the 1930s to the 1980s. Ahu Antman’s essay in the exhibition catalog analyzes the relationships between these artists and larger trends, particularly feminism, in twentieth and twenty-first century art. She touches on the emphasis on empowering women in the Republic, but primarily she examines the ways in which these artists explore a wide range of contemporary approaches to media, subject matter and content, much of it explicitly relating to women in society.

Among the artists shown, the selection of the particular art work does not always stand as an indicator of the artist’s primary contribution to contemporary Turkish art. Gülsün Karamustafa’s Postposition, (1995) five quilts found in a bazaar and framed with gold gilt fabric, are an indicator of the contradictions of kitsch taste and the conservative ideology of those who buy it, only indirectly suggests that artist’s position as a major contemporary artist. Her work encompasses many themes, migration, orientalism, prostitution, women in popular culture, and much more.

The work of Hale Tenger is a crucial early installation by the artist in which she evokes potential violence in society with a great vat of red colored liquid and dozens of swords suspended above. It is not a feminist work, but it addresses the threat of violence which includes women. “The School of Sikimden Aşşa Kasımpaşa (I don’t give a fuck anymore)” 1990, was prompted by a letter bomb that killed a female professor and other acts of violence. Tenger addresses social issues, but cannot be considered a feminist artist; she does not focus on women specifically.

Among benchmark artists is Inci Eviner who has always gone her own way in terms of materials and content. Her current medium is video, but eccentrically. Fluxes of Girls in Europe. ((2010) superimposes videos of almost 70 moving female bodies on a satellite image of Europe. The women are small scale, although large on the map of Europe. They are accompanied by a text with words that describe their actions, “tear,” “stab” (catalog p.159). These women seem to be trying to break free, but failing to do so.

Many of these artists have been prominent for decades. They adopt a wide range of media and subjects, suggesting the real depth of art by women in Turkey. For example, aside from those mentioned, there are several generations of conceptual art (Ayşe Erkman, Canan Beykal, Azade Köker, Gul Ilgaz, Nancy Atakan) , social activism (Nil Yalter, Esra Ersen, Selda Asal, Ipek Duben), references to folk art or history (Selma Gürbüz, Handan Börüteçene), classical art (Candeğer Furtun,) environmental issues ( Neriman Polat, Elif Çelebi, Canan Tolon), and a combination of several of these ( Aydan Murtezaoğlu).

I will focus on a few artists with whom I was not as familiar. Şükran Moral’s provocative video Bordello, 1997, in which the artist herself plays a prostitute, is a wonderful challenge to traditional attitudes . It was actually performed in a brothel on which she hung the sign “Museum of Modern Art” and held a sign declaring that she was “for sale.” ( catalog 174). Nilbar Güreş’ video Undressing (2006) was a delightful send up of the veiling controversy in Turkey and elsewhere, as well as a compelling social commentary. The artist began entirely covered, and step by step took off one head covering after another, each one identified with a name of a specific person, but each one also representing a different social or cultural identity in Turkey. Her work underscores the oversimplifications with which this issue is often defined. Another pair of videos by Aslı Sungu’s Just Like Mother, Just Like Father (2006) also spoke about attitudes to women and what they wear, but here in the context of parental approval, as the artist kept changing between outfits that reflected different identities.

Kezban Arca Batıbeki’s installation from her Cage Projects 2 Kitsch Room Project: “Where To?” was rich with meticulous details that accumulated into a reference to the same urban migration culture that Gülsün comments on.

Güneş Terkol sews images that address identity through dress as well . Gözde Ilkin accumulates, also mainly working with fabric, a serendipitous collection of objects from everyday life. Ilkin is part of a collective called Atılkunst which created an audio tour of the exhibition which brings us back to the beginning of the story in the early twentieth century.

The exhibition with its excellent catalog essays documents the major role that these artists play in contemporary art in Turkey. Many of them are not politically affiliated with feminism per se, but, as suggested in this brief discussion, many of them address topics that engage social issues that concern women. Of course, with any exhibition of this type, there is always a question of why this group was chosen, and other well-known artists ( like Suzy Hug-Levy and Şirin Iskit, just to name two) were omitted. On the whole though, the exhibition is a major contribution to literature on contemporary art in Turkey.

One of the biggest ironies of the exhibition though was the introduction by Emine Erdoğan, the wife of the Prime Minister and the juxtaposition of her attire- elegant, but extremely conservative, with a thorough head covering with the ultra chic and contemporary Oya Eczacıbaşı the wife of the director of the Eczacıbaşı foundation.

This entry was posted on October 26, 2011 and is filed under Turkish Women Artists.