Benny Andrews: The Bicentennial Series predicts America Today *

Liberty ( Study for Trash no. 6) 1971 oil on canvas on painted fabric 78 x 39 3/4

In one of the most potent images in Benny Andrews Bicentennial Series from the 1970s, the Statue of Liberty sucks a lollipop as she sits on top of the stump of a dead tree. Naked men wearing only an army helmet and boots support the stump on a wagon.

Trash, the mural, in collection of Studio Museum, Harlem

In a final full scale mural, Liberty leads a succession of carts, one carrying a “war bitch,” as the artist describes her, and another, a giant penis topped by flowers.

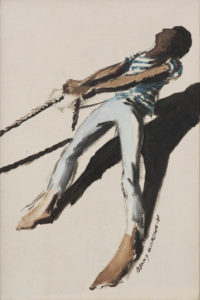

Puller ( Trash Study no. 1,) 1971 oil on linen, 18 x 11 7/8″

Several men, one of them a convict in chains, strain to carry everything off to the garbage dump “Trash,” is one in a series of murals by Benny Andrews painted during the years leading up to the Bicentennial in the early 1970s. His dark vision could have been painted yesterday.

On seeing excerpts from his Bicentennial series at the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in January, I was stunned with the forcefulness of his comments on the abuses of our American institutions. Today, as we struggle against the escalating wave of white supremacist policies from Washington, D.C., they speak to us directly.

During the early 1970s Benny Andrews created BIG paintings as he put it, to provide his own perspective on the 200th anniversary of the Nation. BIG because the mainstream white artists at that time were working big, and he believed his work would stand beside them. He saw that preparations for the Bicentennial were devolving into clichés for African Americans like slave cabins, and great people, he knew there was more to the story than that.

He himself had grown up in a sharecropping family, picking cotton, and he followed an incredible journey, with the support of his family, to become a trained artist based in New York City. But he never forgot his roots in Georgia, the people he knew from his childhood, the strength of the people around him, their creativity, and their perseverance.

The vivid series of paintings, drawings, small studies and large works include six themes: Symbols (1970), Trash (1971), Circle (1972), Sexism (1973-74, War (1974),Utopia (1975).

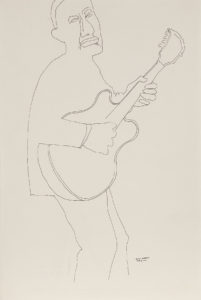

Strummer (Study for Symbols), 1970 india ink on paper 18″ x 12″

His first large work, “Symbols,” paid homage to his roots. In the recent exhibition, we saw drawings for the large finished work now in the collection of the Ulrich Museum at Wichita State University. His spare linear style is as elegant as Ingres. For this first work, he went back to Georgia and sketched his home, his family, a bride and groom, musicians, and in the center of “tree of life.” It appears to be children playing in the tree, but it also seems to be people “hanging” from the tree, clearly a reference to lynching. Nearby two people carry off a dead child.

Since Andrews family has mixed black and white heritage, but all were considered African American, he frequently suggested racial mixing. Even people who are white in his paintings reference his African American community in Georgia. The artist pairs ordinary life, ordinary people, and nightmarish events; a semi-white man sits in judgement in the final “Symbols” mural, on the right. Andrews may be referring to an overseer, or a mixed race business man, his ambiguity is intentional.

He worked in dozens of separate sketches that he then puts together in a larger composition based on multiple panels. In “Symbols,” the space is complex as the imagery pushes forward or recedes into the background, based on strong diagonals that terminate at a tree in the center. In later murals his figures seem to float in an indeterminate space, sometimes framed by viewers, or encircled by odd faceless people.

Collection Studio Museum Harlem Photo: Adam Reich

Trash(1971) is full of anger and sarcasm. He painted it during the Attica prison uprising. By this time Andrews had already founded the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, demanding Black curators and artists in New York Museums, but more important than that, he founded the first prison art program in the country. He was outraged at the failure of American institutions and Trash hauls them off to the junkheap, pulled by both a prisoner and another black man.

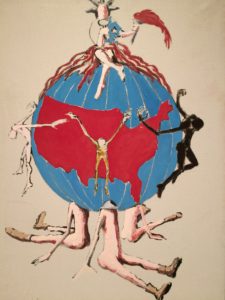

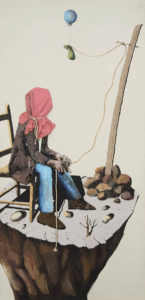

Liberty ( Trash Study no. 2) oil on linen 32 x22″

In the exhibition two studies presented just the Statue of Liberty, as she is disintegrating, in one (Study no 2 for Trash) she sits on top of a globe with the USA facing out, black and white people reaching out to encircle it and underneath propping it up are again the naked military indicated with hats and boots. These self sufficient paintings stand on their own. Also in the exhibition was “the Puller” the man hauling the trash wagon with the Statue of Liberty, braced against the weight. Behind him a black shadow echoes his silhouette.

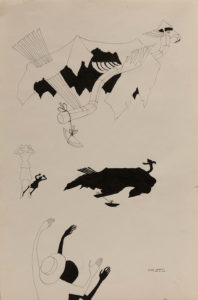

Composition #9 for Trash, 1971 india ink on paper 24″ x 18″ /

Use of shadows is a crucial device in Andrews, they reinforce his imagery, creating a shadow layer, much as blacks experience their lives in a white world.

oil on twelve linen canvases with painted fabric and mixed media collage 120″ x 288″

Circle Study no 33 1972 india ink on paper 12×18″

The mural “Circle” , the only one included in the exhibition, fills one wall of the gallery. Sketches and smaller paintings fill the walls nearby. “Circle” focuses on a bed on which a black/white person sits impaled, his heart carved out and rising above him as a watermelon lifted by an odd pipe like shape (in earlier sketches it was a stove).

Around this tragic figure stand a circle of people both black and white who shake their fists, look horrified, or sit passively in chairs, as the torture unfolds before their eyes.

Tied and helpless, the man on the bed reminds us today of torture inflicted on prisoners in detention, but here the reference is certainly to the tortures of simply living in the US as a dark skinned man. Andrews is the visual partner to James Baldwin who lays bare with words the torture and injustice of living in the US for people of African descent.

Andrews uses fabrics glued directly on the canvas. Thus the bed is stained and dirty made with old cloth, the head is bandaged in an actual sheet/bandage, a dirty cloth wrapped around his genitals like a diaper. That physicality paired with fantastic imagery, a personal surrealism, that relies on the grotesque to warn us of dark realities, penetrates our hearts; the physical additions to the canvas, assembled from found objects and discarded dirty materials, strike into our eyes and into our souls, they rudely speak of poverty, of suffering.

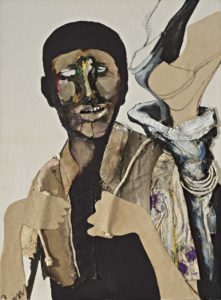

Sexism Study no 24 1973 oil on canvas with painted fabric collage and rope 96 x 50 1/2″

Another work in the cycle “Sexism” appears in the exhibition with several large works. At the entrance to the exhibition we are immediately confronted by a figure covered in a tent like sheet. She appears to be rising from a bed, but she is still caught in the strings held down by odd detritus.

Sexism Study no 8 1973 oil on linen 24 x 22″

Another strange work Sexism Study no 8 appears to be a penis man holding an instrument of torture and wearing strange clawlike shoes. He looks like a rapist with primitive tools. This particular image did not appear in the final large mural

War Study no 3 1974 oil on two stretched linen panels with painted fabric collage 35 x 49 x 1″

War Study no 1, 1974oil and graphite with painted fabric collage 34 x 25 x 1 1/4″

“War” for which a large work was never completed, is featured in two poignant collage paintings, one with a young man dragging a dead body. In “Poverty,” a man with a pink bag tied over his head suggests torture and the impossibility of escape.

Poverty Study no 1-a for War 1974 oil on linen with painted fabric collage with rope 100 x 48 x 2″

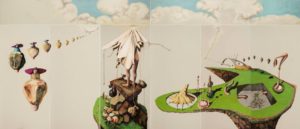

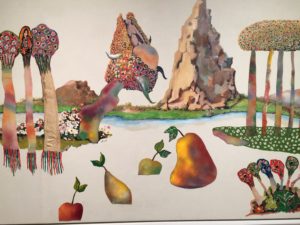

Finally, Andrews created “Utopia”, but because he could see no redeeming feature in humans, he created a fantasy landscape without any people.

Utopia Study no. 8, 1975, oil on linen with painted fabric collage 40 x 60″

Along with his very large mural scale works, and his smaller collage paintings, Andrews draws, and draws and draws.

In this exhibition, these delicate linear studies for the larger works populated by strange creatures or bizarre settings, create a constant dialogue for us with the final murals giving us insight into his thinking. Frequently, he includes shadows for his outlined figures, suggesting even in the briefest encounter with paper, the shadow world still haunts his every move and that of every person of color.

“Surrealism can get out hand real fast, but then the black experience is so ridiculous that surrealism is the best way to express it. I’ve seen the same kind of work coming from prison artists. To get through an oppressive real life, the artists have to live a fantasy life. ”

— Benny Andrews

With the draconian new immigration expulsions declared by a president who has no restraints, the dark shadows are following every vulnerable person, whether they be transgender, disabled, young, old, latino, African American, Asian, Muslim, homeless or poor.

- all works Credit Line: Estate of Benny Andrews/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

- “America Today” is the title of a mural cycle by Thomas Hart Benton painted in 1929 including both the roaring 20s and references to the poverty of the Depression. It makes a telling comparison to Andrews work in its exuberance and celebratory atmosphere that features workers of all types.

This entry was posted on February 24, 2017 and is filed under African American fiction, Arican American history, Art and Activism, Art of Democracy, Black Art, Black HIstory Month, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.