Roger Shimomura Minidoka on my Mind

“I offer this exhibition as a metaphor for the impending threat posed by current times. …” Roger Shimomura 2007

Roger Shimomura’s new work shown in his exhibition “Minidoka on my Mind” at Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle confronts us directly with both the past and the present.

This is Shimomura’s fourth series on the subject of the Japanese Internment during World War II. He based earlier series on his grandmother’s diary, and as he has described it to me recently, memories that have become fact: “memories that were galvanized from retelling and then spawned other memories, and got longer. ”

He was in the camps himself as a very small child, so he does have some memories, but that is not the point of this exhibition. He has made these works in deep conversation with Western modernism, both minimalism and Pop Art, as well as a particular period of Japanese art, Namban.

by Kano Naizen

Azuchi-Momoyama period

Pair of six-fold screens, color on gold-leaf paper

Height 155.5 cm; Width 364.5 cm (each)

(Kobe City Museum)

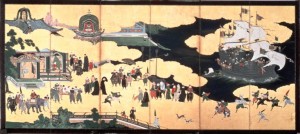

Namban screens as seen here are the work created in response to the arrival of Europeans in Japan during a brief period of time, in the late 17th early 18th century.

Namban means “southern barbarians” and refers to the arrival of Spanish and Portuguese by ship, bringing both commerce and religion. While the subject can find a parallel in the Iraq war invasion, as to how we perceive ourselves vs how the Iraqis perceive us, (certainly as Barbarians), as well as the overlapping of religion and commerce, the comparison also extends to the compositions and subjects of these paintings and their colors. ( This comparison was suggested by a current exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum, Japan Envisions the West, and its symposium, December 1, 2007)

This large Namban screen, ( the right half of a six panel group by Kano Naizen, the whole measures five feet high and over ten feet long) ) uses aerial perspective, a palette of gold and black, and tiny figures very much like Shimomura’s American Infamy above (which is an overwhelming 6 feet high and 10 feet long). In the Namban screen, a large ship on the right looms in the black water The ship bears religious icons and trading items that the captain is planning to trade in Japan.

The screen bears an intriguing comparison to Shimomura’s large painting. In Shimomura’s work the person who is above the scene is not implied but depicted as a large foreground figure with binoculars looking down from a watch tower on the inhabitants of the camp. The camps were in arid desert settings, so the gold ground of the Namban scene is echoed in the yellow of the desert. Between the small structures are many small specific figures, a panorama of types in both paintings. Shimomura declares irrefutably that surveillance controls lives. In the Namban painting that is not so obvious, although the Jesuits were forced to leave Japan in the early 18th century because the shoguns recognized that they were threatening traditional values in Japan.

Shimomura’s smaller paintings are no longer intended to be memories or facts. They are constructions, based on a highly sophisticated transformation of a grid setting into layers of space, insides, outsides, barbed wire and cheap housing, modernism turned back onto itself from utopia to prison. This grid ( so lauded in modernist theoretical discussions) is flat, it barely separates those who are free and those who are not.

In Classmates, the blond blue eyed girl has a dress that touches the shoulder of the Japanese American girl behind the wires. Both hold apples, both are dressed in fashionable clothes, both smile, both are the same age. The wire thin line that separates them is both literal and metaphorical. These girls could be representing today’s shattered friendships as the Immigration and Homeland Security forces sweep into neighborhoods and remove random people ( Arabs? “Immigrants?) for no declared reason, intern them in prison without charges, shatter families, friendships and lives.

The title work Minidoka on My Mind is perhaps the most astonishing. It shows a young boy painting a “minimalist” composition, but here is no red, yellow and blue primaries, or black zips on a white ground referring to the “Stations of the Cross” and inferring higher realities. Here are horizontal and vertical yellow lines and black squares. Looking closer the painting within the painting is an exact replica of the actual construction of the building the child is painting. It is a representation of the idea of prison when imagination is confined to the wall in front of you. It takes the minimalist/grid tradition and turns it on its head. The blackness becomes not an opening, but a closure, the empty spaces that we have glibly interpreted in Mondrian’s subtle compositions, are now flat, cheap walls. The child is obsessively painting a row of dots, these are the nails that hold the flimsy structure together. The grid continues to the left of the building and the child, scoring the landscape, the sky, and the world with its rough wire lines.

Shimomura and other members of his generation are offering information on the history of racism in this country with their work on this topic. It is now more current than ever.

Shimomura fears that the persistance of racism in our society is not fully grasped by the younger generation, (70 per cent of Asian Americans, for example, are in biracial relationships.)

This little boy is about much more than painting, it is about forgetting and willfully eliminating the larger context of what that internment camp meant in the context of the large social forces that shape decisions. He cannot see beyond the wall that he is painting, but we can. We are outside his space, looking down on him, like the soldier who is standing in the watch tower. Surveillance is available to us, but we do nothing to liberate this child, to understand the conditions of imprisonment, or to ensure that laws will prevent it. In the end Shimomura’s work turns back to us as the perpetrators. We are still outside the prison, but for how long will we remain there, if we ignore reality. Our position is not one of power, it is one of ignorance. The little boy understands his situation more completely than we do.

This entry was posted on December 1, 2007 and is filed under Roger Shimomura.