The William Kentridge Moment in New York CIty

I was privileged to be there, during what was referred to as the “William Kentridge moment” in New York City. It combined his major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, “Five Themes”, a lecture at the New York Public Library “Learning from the Absurd” and his groundbreaking production of “The Nose” at the Metropolitan Opera. William Kentridge directed, made the set designs (with Sabine Theunissen), and staging, (including a nose the size of a human being dancing around and even singing ), proscenium curtain, and banner. Also part of his team was Urs Schonebaum from Munich, who did the lighting, and Catherine Meyburgh from South Africa who did the video compostions.

I was privileged to be there, during what was referred to as the “William Kentridge moment” in New York City. It combined his major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, “Five Themes”, a lecture at the New York Public Library “Learning from the Absurd” and his groundbreaking production of “The Nose” at the Metropolitan Opera. William Kentridge directed, made the set designs (with Sabine Theunissen), and staging, (including a nose the size of a human being dancing around and even singing ), proscenium curtain, and banner. Also part of his team was Urs Schonebaum from Munich, who did the lighting, and Catherine Meyburgh from South Africa who did the video compostions.

Dimitri Shostakovich wrote the opera in 1928 at the age of 22. It was produced in 1930 ( in Leningrad/St. Petersburg). It was not performed in the Soviet Union again until 1974. Shostakovich survived Stalinism, unlike many of his brilliant contemporaries, but he was shattered by it. “The Nose” represents a watershed moment of brilliant experimentation.

At the Metropolitan Opera the music was conducted by world famous Shostakovich expert Valery Gergiev. Its extraordinary music is atonal and non lyrical, as well as filled with satirical references to traditional musical forms like folk music and chorales. But its main characteristic is the incredible use of unpitched percussion. It is based on a Gogol short story of ten pages called The Nose, written in 1836. The nose is a character on its own. The owner of the nose wakes up to discover his nose is gone, he has various adventures ( as the nose dances around the stage in both real time and on the animated film sequences that Kentridge created, borrowing from all sorts of Russian, modernist sources.) The extraordinary singing by Paulo Szot, who played Kovalyov, the mid level bureaucrat who lost his nose when he had a shave ( it fell into the barber’s flour supply and reappeared in his bread the next morning) and therefore his position in the world, is a Brazilian baritone who sang almost non stop for one and a half hours. He was thrilling. I am now a convert to opera.

Kentridge animated the stage and its surroundings with the Russian avant garde art of Lissitzky, Malevich, with moving red squares, black lines, red circles. The costumes ( by Greta Goiris) drew on Popova’s famed constructivist inspired dresses. The proscenium curtain was a giant collage with all sorts of amusing references, such as a list of the hierarchies of people under the tsar that starts with angels, the tsar, with actors way down the list with slaves, then thieves, pirates, gypsies, Jews/Muslims, animals, plants and finally stones. Then there was the hierarchy in Stalinist Russia, self seekers, loafers, careerists, morally corrupt, cadets menshiviks, democratic centralists, workers opposition, three times contemptible degenerates. Then there is the hierarchy ( not on the curtain, but recited in the lecture) of apartheid South Africa, Whites, Japanese, Chinese, Other Asians, Indian, colored, black. And we know about Mexico and its mind bogglingly complex castata. Which is to say that all hierarchies are futile exercises in arbitrary and meaningless status driven by the desire for power. The Nose, short story, opera, performance all refer to the absurdity of stature and how it is endowed.

Kentridge has also done a performance that related directly to the Opera, “I am not me, The Horse is Not Mine,” which I wrote about when I saw it last year ( search the blog under Kentridge). His theme is the great aspirations and tragic failure of the Russian Revolution and its artists. And yet, the exuberance of his set and the staging of the absurdist play suggests his love of this art as well as its hopes. The performance began with an animation of the silhouette of a marching worker carrying a red flag across the stage. ( We all know about the importance of processions for Kentridge with the layers of meaning from protest to desperation)

Kentridge as a white South African and genre defying artist, working in animated film, drawing, prints, and collage, is deeply political, but he defined it, in a conversation at the New York Public Library, as conveying the political as surprising, as having an “uncertain ending.” His work is laced with the humor of the Cabaret Voltaire defiance of World War I and its absurd performances. He throws us off from any certainty, he plays with the ridiculous, the illogical, the embarrassing , the accidental, the digressive, selecting from various experimental actions what will work in his performances. He has given us “sketches” in a DVD accompanying his book Five Themes that include some of the ideas he didn’t use. He is absolutely in tune with Gogol and Shostakovich themselves, who perpetuated the same kind of disruptions with the novel and music respectively.

His animated films, including the story of Soho Ekstein, the greedy capitalist, and Felix Teitelbaum the neurotic lover, along with Mrs. Eckstein are about greed and love (love as a type of greed). His technique of animating drawings by sequential erasers is poignent and deeply moving. Ubu and the Truth Commission, with Ubu referring back to another Dada character, the impossibly self important despot Ubu from the Alfred Jarry play, is another performance that uses puppets, as he did last year in “The Return of Ulysses.” “Ubu Tells the Truth” a film from 1997 has some shockingly violent sequences, including a person being chopped up and exploded three times.

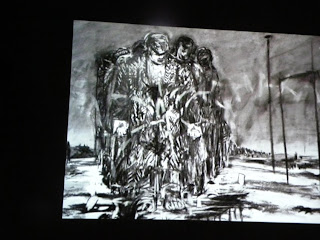

From the Soho and Felix group, here is a line of starving workers and nearby the greedy capitalist stuffs his face from Kentridge’s first film, Johannesburg, the Second Greatest City after Paris, 1989. One vivid image in this film was the capitalist using a coffee press, and the press goes right down into the deep underground and sets off charges that explode into the veins of a mine.

The Nose opera, the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, the lecture, all together comprise the astonishing work of one of the most extraordinary artists working today. He draws on not only Russian avant-garde art of the 1920s and Dada, but also on German Expressionism, that great style of political protest art in Germany.

Living in post apartheid South Africa and having lived tin South Africa all his life, he is acutely aware of the absurdity of contrived hierarchies that make some people superior to other people. He is undermining those certainties of who is important and who is not, and Gogol’s short story and Shostakovich’s opera with their wandering nose looking for status, removing it from its owner, and giving it to another person of “higher rank”, etc, is a perfect ( he would say literal) example of the absurdity of who is powerful and who is not. That is the most subversive political statement I can imagine.

Of course, I am myself very opinionated about politics, and I feel that opinions and taking a stand for what I believe in is important. So why does Kentridge appeal to me so much? Because I can feel that underlying the wonderful humor, the absurdities, there is a man who cares very, very deeply about humanity. His work “the Black Box,” addressing the ravaging of Africa by whites in the nineteenth century, is filled with pathos. The arbitrary slaughter of rhinocerous shown with vintage footage, connects directly to our continuing random slaughter of the planet for sport and greed.

But Kentridge also believes that humor, of which he makes such use in many of his works, can encompass the experience of the many, while tragedy only the experience of the individual. So he relies on humor, our collective laughter, and our recognition of our shared humanity as we laugh, to get ideas across.

In The Nose performance, and the related section of MOMA exhibition, Bukharin, that most deeply intellectual of the early Russian Revolutionary idealists, speaks up for humanity, may also speak for Kentridge, even as the words are those of a man who is laughed at, and, ultimately, condemned.

There is a lot more to say, but I will stop there for now. Kentridge will be the Conclusion of my book on Art and Politics Now so buy the book next summer when it comes out for more analysis.

Kentridge at the New York Public Library.

PS And the contrast could not have been starker with the shallow and failed works in the 2010 Whitney Biennial. I hope those artists attend Kentridge’s exhibition.

This entry was posted on March 20, 2010 and is filed under "the Kentridge moment", South Africa, The Nose, the Whitney Biennial, William Kentridge.