Art in Cuba Now Part I

Art in Cuba December 2011

Gerardo Mosquera: “For the third world “primitive” is not a matter of resuscitating pre capitalist solutions which correspond to a state when internal evolution was interrupted by Eurocentric expansion of capitalism. It is a matter of making Western art in the (Third World) way and for the “(Third World) benefit. ”

( as quoted in Louis Camnitzer, New Art in Cuba, 2004.

While little that I saw in Cuba was referring to the primitive, an important fact in itself, this wonderful quote by a foremost Cuban art critic, suggests the complexity of the art in Cuba. I met with about thirty artists and was able to witness the vast differences of accessibility to international connections, money, and materials. They ranged from individual artists based in beautiful homes to artists working collectively and collaboratively and getting by on four jobs. They were all highly trained in the government supported art schools, the high school Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes San Alejandro and the Istituto Superior del Arte.

On the first day we met a young graphic artist at the Taller de Grafica Experimental named Alejandro Sainz Alfonso. I bought a print from him: a Greek warrior carrying a paper airplane on his shoulders. That seemed like a great introduction to the unpredictable week ahead. The Taller was founded in 1962 and 150 artists have passed through it over the years. Today it has about 20 – 30 members. The printmaking is traditional media: woodblocks, linoleum, lithography, etching.

Most of the artists I am going to write about do not have websites. Access to the internet is limited in Cuba. Think about how that changes your view of the world. Artists who have married foreigners have more access, mobility and possibilities to create websites. They seem to also have more money. One example is Reinaldo Ortega Sardiñas who is married to a Spanish wife and recently returned from two years in Spain. His work is sculpture, multimedia installation. He gave me a CD of his work (in itself an indication of resources) and told me (in English) that he does have access to the internet. His work involves some impressively expensive materials and his multimedia installations are large scale but provocative, as are his photographs.

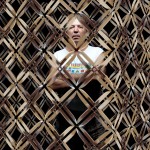

I was struck by the photographic series, images of people entrapped by what appears to be a net made of plastic at first sight until you discover that it is made of knives or scissors. His multimedia installation was accompanied by a dance performance by the group Danz Abierta, also with funding from abroad and an enormously creative family. Danz Albierta are even on You Tube: they have performed in NYC at Jacob’s Pillow. The performance that we saw, Mal Son ( bad song – a reference to the traditional Cuban Son music), was intense: dancers abruptly walking around three short walls of a small space, with loud repetitive music– it was claustrophobic, and entrapped, like the large photographs by Sardiñas. On the back wall were filmed images of the dancers repeatedly climbing stairs. The version performed in the US was very different, as seen on these You Tube videoes: the stage was larger, so the feeling of claustrophobia was less.

For me the most provocative artists that I met were the collaborative pair Celia /Yunior, as they are known (Celia González and Yunior Aguiar). These artists work with contemporary Cuban social structures, regulations, and boundaries as they are rapidly changing. This image is from a piece filmed in a formerly elegant swimming pool, now surrounded by jagged chunks of concrete and completely unmaintained. The two artists brought some blow up rafts and floated around as if it was a luxurious place to be. Their work frequently turns on the contradictions of public and private realities.

One of their works, Bojeo, (Coasting), 2006 – 2008 involved a grant to go to Trinidad and Tobago where they played at being tourists with tourist cliché photographs, as they called Cuban hotels to inquire about their facilities. The law at that time was that Cuban residents could not stay in their own tourist hotels unless they had a foreign residence permit. So as they went around the beautiful beaches in Trinidad and Tobago, the sound track is a series of phone calls to resorts in Cuba as learned about all of the incredible eco resorts in Cuba, but in the end they were told they could not stay at any of the hotels in Cuba. The law has since changed, but the atmosphere toward Cubans in tourist hotels is still uncomfortable. For example, they are often asked for identity cards for no reason, or they are made to feel unwelcome. The piece beautifully captures both the beauty and the clichés of the Caribbean tourist life, the amazing resources that Cuba has as an ecotourism destination, and an example of the arbitrary oppression of Cuban citizens.

Another piece by Celia/Yunior called Habana 15 segundos (Havana 15 seconds) is simply recording the replacement of a Soviet era air conditioner with a Chinese one. At the moment of exchange we see through the hole in the wall to the street outside. The exchange was meant to provide more energy efficient cooling, but of course the basic reality didn’t change much.

Another piece by Celia/Yunior called Habana 15 segundos (Havana 15 seconds) is simply recording the replacement of a Soviet era air conditioner with a Chinese one. At the moment of exchange we see through the hole in the wall to the street outside. The exchange was meant to provide more energy efficient cooling, but of course the basic reality didn’t change much.

A provocative work that Celia/ Yunior created in collaboration with a group of friends is En Medio de Qué as part of an exhibition called Curators Go Home 2008. Their collaborators are Javier Castro, Luis Gárciga, Renier Quer and Grethell Rasúa. They invited friends to write on a wall about when they had been censored, either partially or completely, as well as who was the person or institution that censored them. The result was a picture of constantly changing, serendipitous censorship, dispersed information that could not be predictably mapped or even verified. The fluidity of the relationships between artists, institutions, curators, and the “system” in Cuba is its primary characteristic.

The piece became more intense when it emerged that someone from the US Interest Office had been invited to the exhibition, and the Cuban government ended by accusing the artists of being “traitors of the motherland,” a shocking experience for them. They were able to successfully defend themselves against the charge. The work exposed both the convoluted character of censorship procedures, and the ever present threat of an oppressive regime that took any exposure seriously.

This piece was created in an independent space, El Espacio Aglutinador, run by Sandra Ceballos, with various collaborators since 1994. The space is in her private home, which means that what she does cannot be censored or stopped. I will talk more about her work and space in the next installment.

“Private” home until just a month ago was not quite an accurate term, as Cubans were not allowed to sell their homes, only trade them for equivalent value. They could will them when they died. Recently though the law has changed to allow Cubans to sell their homes. Since no one has any capital to do that, one can’t help but wonder if the multinational banks are circling for new prey for their mortgages. We shall see. Up until the law was changed, though, the only piece of land that a Cuban citizen could legally own was their cemetery plot. So Celia/Yunior made a piece about that in Reserve in 2010 by digging out Celia’s back yard with an area of the same size and projecting onto it the words “Derecho Perpetuo.

The title refers to the fact that in Cuba if you own land you have a perpetual right to it, but if you don’t develop it, it reverts to the State. Of course you will always have the right to your grave! When you are dead all your rights are permanent.

This entry was posted on December 22, 2011 and is filed under Cuban Art 2011.