Constructing Black History: The Present and the Absent

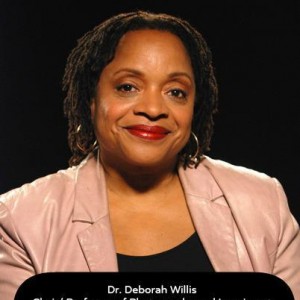

Dr. Deborah Willis, Chair and Professor of Photography and Imaging at Tisch School of the Arts, New York University, spoke to a packed and enthusiastic audience at the Seattle Art Museum on December 14 on the roles of “race, representation and gender” within works of art. Dr. Willis spoke about a few of the works featured in “Elles: Women Artists from the Centre Pompidou, Paris” but she also integrated the show, with an emphasis on representations of and by African American women.

The general theme was that the display of the female body reflects how we interpret the world.

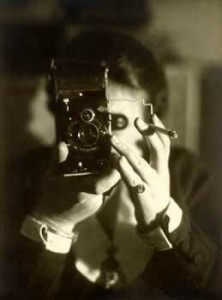

She deftly began with a reference to Germaine Krull’s amazing 1925 Self Portrait holding a camera and smoking a cigarette, reflected in a mirror. This portrait tells us so much about the new women who were subjects rather than objects in the early 20th century.

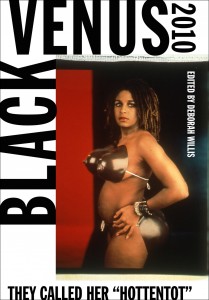

Next, she went back to the mid 19th century images of the “Hottentat Venus,” about which she has edited a book Black Venus 2010: They Called her Hottentat .

Moving forward from there, she showed an amazing runaway slave advertisement with a carte de visite (!!) image of a slave, cut in half. Certainly a carte de visite of a slave suggests a concubine relationship with a master who would have the money to commission this “visiting card” an irony for a slave, to say the least. Cutting it suggests the attack of the master on the woman who refused to submit her life to him. I got many insights into that slave/concubine relationship in Isabel Allende’s Island Beneath the Sea in which the main character is enslaved to a man who forces sex on her from the time of her adolescence.

From the early 20th century, we saw Florestine Collins as a black photographer from New Orleans who had a flourishing career for decades. Carl Van Vechten’s famous portrait of Zora Neale Hurston, the famous anthropologist, is an intimate image of an incredibly important woman.

Willis then moved on to the theme of “women who love their bodies” like movie stars, and women photographers such as Dora Maar, liberated by new mores and new equipment. Of course Germaine Krull is one of those.

She concluded with various recent women photographers represented in the show and Carrie Mae Weems, who should have been included!

The only African Americans on exhibit in SAM’s current shows are Adrian Piper and Lorna Simpson.

Marita Dingus is on permanent display in the African galleries with her amazing 400 men and 200 women of African descent. ( this is a detail of one figure).

For another perspective go to the Northwest African African American Museum to see the beautiful exhibition by Carletta Carrington Wilson “book of the bound.”

The museum has opened a new gallery with a wonderful intimate scale for this special exhibition which continues until March 10. Carrington Wilson is a poet and spoken word performer as well as a visual artist. In this exhibition she has given us 22 books, many of them bound shut, with ornate covers of many materials, bone, lace, newspaper, fabrics, string, jewels and much more.

The theme of the exhibition is that slaves were silenced, their narratives lost.

Carrington Wilson uses fabric as the means of suggesting the connection of trade, money and the “thread-bare body”: the wealth of the traders was based on the bodies of the slaves. As the artist explains in the brochure of the exhibition:

“Three vessels, the body, the book, and the ship form an intimate connection in the works of “book of the bound.” My work attempts to enter into mysteries binding bodies of flesh to the bodies of land, water, and text that forged and formed the social fabric of our hunger-haunted history”

Her collaged covers become a song to those who could not fill these books with their stories. In some cases the books are opened in a series of pages, accordion pleated, standing, or other formats. We see references to those who would have been in those pages. Each book has a poetic title, and often also a poem.

But the significance of the use of fabrics is profound. The wall label explains the relationship of cloth and slave further:

“The essence of the ship, the book and the body is held in the cloth of the collages. Merchants could not have sailed these ships to Africa without canvas sails. Because European slavers often traded fine fabrics like silk and velvet in exchange for bodies, Wilson believes the stories of their bodies remain in the cloth.”

Carrington Wilson also includes stacks of books whose titles create found poetry. We are invited to do the same thing. This seemingly serendipitous project is revealing. The opportunity for us to create found poetry that points toward issues of the slave trade is empowering.

To view Carletta Carrington Wilson’s artwork see her website

Don’t miss Carletta Carrington Wilson speaking about the exhibition on January 10, 2012 7-9PM at the Northwest African American Museum

This entry was posted on December 27, 2012 and is filed under Arican American history, Women Artists.