Women Artists in Seattle Part II

This fall in Seattle exhibitions by women artists, along with events, such as lectures and even a symposium, have proliferated so rapidly, it was difficult to keep up with them. Some inspired by “Elles” at the Seattle Art Museum, the first exhibition discussed here. Some coincided accidentally as in the second exhibition. Taken collectively, all of these exhibitions and events allow us to think about women, art, and feminism in 2012. How is it different from the 1960s and later twentieth century art?

Part I Social Order: Women Artists from Iran, India and Afghanistan,

This ambitious photography exhibition at the PhotoCenter NW included well known Iranian photographer Shadi Ghadirian, as well as Priya Kambli, Annu Palakunnathu Matthew, Manjari Sharma (all South Asian either in origin or currently) and Gazelle Samizay (born in Afghanistan). Each of these artists is exploring a personal journey, obsession, cultural contradiction, or transcultural ambiguity.

Priya Kambli conveys the sense of divided identity that results from immigration. This is a topic that several contemporary South Asian novelists have addressed so effectively, most famously in The Namesake, by Jumpha Lahiri which was made into a film. Her first short story collection, Interpreter of Maladies, also about difficult India-US transitions, won a Pulitzer Prize in 2000, suggesting how potent this topic can be.

Priya Kambli’s format on display here juxtaposes three photographs in a narrow strip, already implying constriction. She presents disjunctions of her childhood and her present realities, her separation from her roots, and her efforts to come to terms with her current life. The cultural references are intentionally elusive and even opaque to a person unversed in Indian culture (like myself). “Muma Baba and Me,” ( from the “Color Falls Down” series) has a loving (wedding?) photograph of her parents in the center, and two partial photographs of herself, one showing her back and her arm, the other her neck and the back of her head. Her parents are facing each other, seated in chairs, fully represented, while she faces away, clearly far away from them both emotionally and physically. The partial view of her body suggests how much she has left behind.

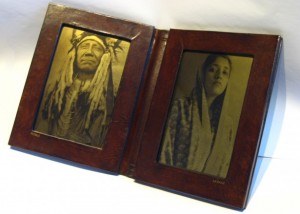

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew currently lives in the US; she uses historical photography of nineteenth century Native Americans as a point of departure in these works; in this series she is amusingly but pointedly commenting on the confusion that dates from Columbus of Indians from India and Native people in the Americas. She pairs an original 19th c image with a contemporary image of herself with the same topic (and antique photographic medium) , underscoring both the racism of the original posed image, the parallel history of colonialisms, and the contemporary confusions with which she lives.

The third South Asian artist Manjari Sharma, who lives in India, shows “Darshan” (sight, vision), one of a series of nine photographic reconstructions of Hindu Gods and Goddesses (only four have been completed) . The artist employs 35 craftsmen to construct the image. The photograph shown in this exhibition is a small version: her intent is to display all nine reconstructions as six foot tall photographs, complete with incense, lighting, and prayers, an immersive environment that will certainly convey the power of “darshan” more profoundly. Even in the reduced scale shown the impact is dazzling.

Shadi Ghadirian lives in Tehran. She showed two different sets of work, the first, her well known self- portraits based on Qajar Dynasty photographic motifs, substituting herself for the elites of the historical images posed against ornate backgrounds, but updated with something contemporary, such as a vacuum cleaner or a boom box. These are the works that made her famous.

A second set of photographs are still lifes such as a bowl of fruit or a cigarette case, into which the artist has inserted a hand grenade or a bullet. Ghadirian gives us the intrusion of war, terror, and even implied killing, into the bourgeois middle class life.

Finally, Gazelle Samizay showed two videos, “Upon my Daughter,” and “This Will Be the Last-,” on the theme of women’s claustrophobia and helplessness in a marriage ritual, and in the marriage itself, an overwhelmingly important theme in Afghanistan, where women even set themselves on fire to escape an abusive environment.

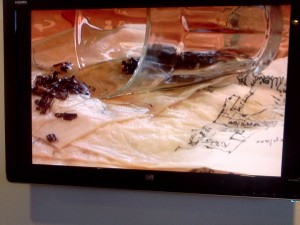

Her third video “9409 miles” is poignant: as her mother prepares tea, her father intensely draws the house he designed and left behind in Afghanistan, but in the end tea spills on the fragile ink drawings (we only see the hands and the table).

Part II Territorial Trappings

Native American artist Tanis S’eiltin’s exhibition at Seattle Central Community College brought together her Tlingit heritage and contemporary issues relating to intersections of white and Native culture. When Europeans introduced exploitative technology and resource extraction, they were able to subdue and exploit local populations. Indigenous cultures were embedded in capitalist society. They were no longer able to be self-sufficient.

In this new installation, S’eiltin’s theme is Native ties to the fur trade that continued right into her childhood. Fashions such as fur hats made from sea otters, or fur jackets from lynx hides directly benefitted the livelihoods of indigenous peoples, but also impacted their traditional relationships to the natural world. The ambiguity of this economic trade-off is suggested in the gallery with a neon sign reading “Trade” backwards.

Tanis’s father was a good trapper, and he was even said to have wiped out the lynx in Skagway, Alaska. She remembered the furs as part of her subsistence life in her early years (she is now a Professor of Art at Fairhaven College, Bellingham).

In the installation we see memories of skins, re-created on transparent paper that have elusive images of native emblems and tools, hanging from the ceiling.

A real lynx fur and a real trap were part of the installation, their physical reality a stark and crucial contrast to the abstraction of the paper skins.

At the end of the gallery whale baleen sieves hung from the ceiling. In a whale’s mouth, baleens are up to thirty feet long; they have little hairs that collect plankton and food particles. The baleen was used as stays in garments like corsets, another resource extracted from whales.

The main theme of “Territorial Trappings” is that Indigenous peoples participate in practices that plunder resources. There is no absolute dichotomy of holistic native culture and marauding European culture. For over 100 years, native peoples have depended on the income from harvesting and trapping.

At the same time, as the artist told me, in Alaska, life is still based less on consumerism and more in a belief in making do with what you have. Skagway, home to the cruise industry, about which S’eiltin has done another installation, writes that contradiction large. It has a small, fairly impoverished permanent population, but 8000 people invade the city during the cruise season. Certainly the income from those cruises helps people to survive, at the same time that the industry itself represents massive waste of resources and pollution.

This entry was posted on December 20, 2012 and is filed under art criticism, Conceptual Art, Contemporary Art, democracy, Feminism, Feminism, Gazelle Samizay, indians, Iran, Iranian Women, Photography, Women Artists.