Sopheap Pich revisited

In November 2011 Sopheap Pich came to Seattle for a one person exhibition at the Henry Art Gallery. He also created designs for a play about the experience of Cambodian refugees. I wrote about these in my blog.

Although at that time he was already having a one person exhibition in New York City, he has since become a star, showing in Europe at major international exhibitions, and most recently, in a one person show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and a second one person show in NYC at Tyler Rollins.

Sopheap Pich fascinates me with his balance of abstracted, but easily recognized, form, material, and content. He has detailed labels for his work which means that we cannot mistaken the deeper meaning of the work, even as we experience his sense of beauty, a beauty that is forged through his great suffering as a child and young adult and that of his fellow Cambodians.

Even as we are deporting Cambodians who came here as children with their parents, because of a minor teenage offense for which they have already paid their time, ( as seen in the film Sentenced Home), Sopheap courageously chose to return to Cambodia in 2003. He went through a major transformation of his work and rediscovered his ancestral heritage, working with rattan and bamboo.

His success means that he can employ people to help with his work:the skills that he uses along with his helpers, are traditional skills, harvesting, boiling, cutting, weaving. He is keeping those skills alive, transforming their purpose, and telling the world about Cambodia, its history, its poetry, its sense of nature based abstraction, the scars of its wars both visible and invisible, and now also, the scars of greed and development.

As we look at his work, we sense all of those aspects, but in no work more than in his exquisite Buddha 2, 2009. The Buddha has only a head and shoulders, the body is unformed and the streams of rattan hang down to the floor, their tips dipped in red. The Buddha is in a gallery with historical Buddhas of Cambodia, it seems to be carrying on a conversation with those Buddhas, to be speaking from today to the past, to be saying, I am scarred, my form is disintegrating, but I still survive. The artist’s wonderful idea to embed his works in the historical galleries of Cambodian art is nowhere more resonant than in this room. It made my heart stop for its beauty and its tragedy.

He spoke on the label about living as a child in Battambang near a Buddhist temple that he passed with water buffalo he was taking to a rice field. Inside of the temple he saw bloodstains, from the violent murders of the Khmer Rouge. At that time his family were still living on their own, not long after they were forced to move to a Khmer Rouge camp, where they did forced labor. I was stunned that a person could experience so much trauma and change in their life and survive to create this great art. From herding buffalo to an art exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but also staying true to himself, at the same time that he is a celebrity in the art world.

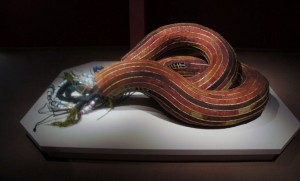

The Morning Glory of 2011 sprawls across the floor of the Metropolitan. It seems lazy and lush, somnolent almost. The artist explains that this was a primary source of nourishment during the Pol Pot regime, and therefore a time of starvation, as morning glories have no nutritional value. It also represents a false glory, it blooms and quickly dies immediately, The sculpture includes a blooming, a fading, and a budding flower. It draws on the artist’s knowledge of the plant from the inside out.

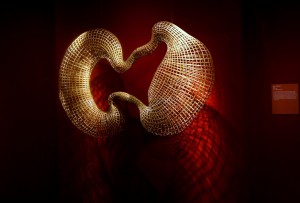

Another piece, the double stomachs, also speaks of not only an organ, but also an indirect reference to starvation and the bloated stomachs of undernourished children. These swelling forms seem to dance in the gallery, in a strange partnership of swollen shapes.

Junk Nutrient represents an intestine( made of woven ratan and rubber detritus) stuffed with trash that is spilling out the end. It was trash taken from a lake where Sopheap had his studio, but in this vivid image it refers to the pollution of the body and the mind, as people are transformed by “progress” and development.

The tower of Upstream, based on the fish trap from his family’s traditions, inserts itself as a peasant tradition into the high art of an ornate ceiling.

And finally works that appear as minimalist grids, but which are made from beeswak, tree resin, dirt, and make reference to the destruction of a beautiful valley by development based on greed. We can feel the scarring, burning of nature in these subtle reliefs.

These current pieces address present day Cambodia. The grids are abstractions, but here too, we can be fooled into simply seeing them through our trite Western cliches. Oh grids, yes, minimalism, but actually there is a long tradition of abstracting from nature in Cambodia.

( this is a detailed close up view)

The roots of these abstractions are deep in Cambodia’s past. We like to think that US artists, or European artists, discovered abstraction, but we know that it is an old old tradition. The artist makes clear that the materials are specific to this location and speak to his own sense of loss at the destruction of the land.

At the end of the exhibition at the Metropolitan was a short video showing the way in which the artist gathers the bamboo and rattan from the forest and, with his assistants, make it usable for art. We in the West know rattan and cane chairs, but the material has been used for centuries for practical purposes. Sopheap takes those original forms and transforms them into contemporary sculptures that speak to everyone. It is sad and not surprising that all the reviews of this exhibition emphasize the artist’s process and materials, his forms, his abstractions, with no reference to his content. The artist himself has declared he is not a political artist, and he was contrasted to other more political artists in a recent Art in America article.

But I see this work as deeply political, in the sense that it is telling us so much that we don’t know with his materials and form. These sculptures are pure poetry, but poetry with a point, a point about war, hunger, starvation, greed.

Another exhibition about Cambodia at Asia Society by Vandy Rattana called “Bomb Ponds” was also poetic and moving. Photographs of apparently bucolic scenes of ponds in the midst of rural farmlands are actually something quite different.

A series of videos interviewed contemporary farmers about the holes left by bombs from 1970s, their toxicity, their damage to the land, their ongoing presence, their dangers.

As the US has long since forgotten our Cambodian carpet bombing, the scars of that war live on in the land.

These long range environmental aspects of war are rarely addressed by contemporary artists. Sopheap Pich uses the metal recycled from left over war materals to make wire that holds together his rattan structures. But much more often this detritus is simply a toxic presence in the land for generations of people who are the innocent victims of war.

This entry was posted on June 22, 2013 and is filed under Art and Ecology, art criticism.