Art and Politics at the Seattle International Film Festival

There were powerful politics in many of the films at the Seattle International Film Festival (SIFF). The back stories for the making of the films as well as the politics of their release are frequently almost as dramatic as the films themselves, filled with politics, protest, government suppressions and creative courage. All of the movies exist in various relationships to documentary, fiction, real life, and real world events.

Part I A World Not Ours directed by Mahdi Fleifel

I think the film that affected me the most was A World Not Ours shot from the inside of a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon that the filmmaker, Mahdi Fleifel, had lived in as a child. Many members of his family are still there.

I just re read the program notes and I could hardly believe that it was the same movie I had seen. It is characterized as “funny, nostalgic and uniquely engaging.” Actually it was depressing, claustrophobic and deeply revealing.

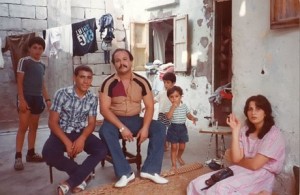

The film was shot with a hand held camera. The filmmaker’s father, and mother “escaped” ( they are still refugees) into the middle class because his father had a job in Dubai, where Mahdi and his brother were born. It is not clear how his father managed to leave, but the filmmaker’s uncle and grandfather are still there. The family has a tradition of home movies, so in making this film Mahdi Fleifel was able to draw on those early films, both in Dubai and in the refugee camp, Ain El Helweh, where he lived as a child.

We have all heard about Palestinian refugee camps. But never had I gained such a sense of what it is like to actually live in one, be trapped in one, unable to work or leave. This one has 70,000 people in one kilometer. It has been in existence for 60 years. The people have small homes, but what really depressed me was the fact that so many young people are not allowed to work, leave, or do anything. This fact was conveyed through the filmmakers interaction with his friend Abu Eyad, the real star of the movie. We see his life up close, we see his story, we hear his words, we understand what it means to be a perfectly competent young man and unable to get a job (he has a job with the PLO part time, but he quits it in disgust with Arafat at a certain point).

II Closed Curtain directed by Jafar Panahi

Also conveying a sense of being confined was Closed Curtain. Film director Jafar Panahi is under house arrest in Iran. This is the second film I have seen that he has made since he was put under house arrest. The first was This is Not a Film (smuggled out of Iran in a cake). The Iranian director is currently under house arrest, convicted of “making propaganda against the system” and banned from writing scripts or shooting pictures for the next 20 years according to the Guardian newspaper. The first film was simply his daily life in his apartment, the second film, set in his seaside villa, suggests isolation, paranoia, and melodrama. The filmmaker who was almost the sole actor in This is Not A Film, here arrives late in the movie, and the characters that precede him are then understood to be figments of his imagination.

The curtains are closed for most of the movie, the sense of oppression and claustrophobia is everywhere. A subplot is a pet dog and the careful removal of his litter on a regular basis; Panahi takes the trivial act and makes it into state resistance: the dog is also in hiding because of the government policy of killing pet dogs.

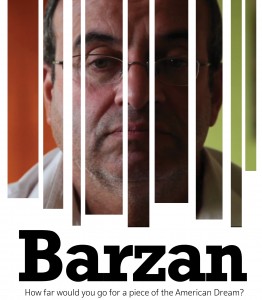

III Barzan directed by Seattle Globalist

Also making reference to confinement is Barzan a film by Seattle Globalist, a University of Washington Department of Communications program (separately funded). Barzan was the nickname for a man who was living in Bellevue. Because of the complexity of the story I will quote description from the Globalist website

“Barzan is a film about a man who simultaneously embodies two fundamental myths of 21st century America: the American dream of peace and prosperity and the bloodthirsty terrorist bent on destroying that dream.

Sam “Barzan” Malkandi, an Iraqi refugee to the US and beloved father, was working toward his piece of the American Dream in a Seattle suburb. But a footnote in ‘The 9/11 Commission Report,’ connecting him to a high-level Al-Qaeda operative through his childhood nickname, changed everything.”

The film is also about detention and deportation. The procedures that Malkandi goes through once he is accused and detained are extraordinary: he appeals before a judge ( immigrants in detention do not have access to the jury system because it is a civil procedure not a criminal procedure, although the detainees are treated like criminals as we saw clearly in the film. Visitations are behind glass separation barriers. And the health rules for criminals are not followed, re diet, healthcare, outdoor time.

IV Dirty Wars directed by Richard Rowley

I saw Dirty Wars as part of the festival, but it is now in theaters and it is an extraordinary film. Jeremy Scahill is the leading actor, the director is Richard Rowley and the film score is by the amazing Kronos Quartet. Scahill narrates the story of his investigations of atrocities and we follow him as he visits families with suffering and tragedies that the US has caused by its mistakes and its intentions. Scahill starts in Eastern Afghanistan in a small village, then he moves on to Yemen and the killing of two Americans. These are stories of the massacre of innocents and the US disregard for human rights, international law, or any normal concern for human life, but the flavor of the film is a mystery, and what he uncovers is truly evil. I had the good fortune of hearing Jeremy Scahill speak about the film during SIFF. He is modest and understated. How he can have so much courage and persistence is unbelievable. The book is huge, but we should all buy it to support him.

V After the Battle directed by Yousry Nasrallah

With Egypt erupting once again, the film After the Battle is all the more timely. It follows a story of one of the men from the tourist trade at the pyramids who rides his camel into Tahrir Square. He is ostracized by many people for the initial act and further because he was pulled off his camel and beaten. His children are bullied and mocked in school. A liberal young woman working for an NGO becomes infatuated by him and his family, and the complexities of his story emerge. It is a story of class, economics, and power relationships. The movie was shot in real time, and near the end, the film making is actually caught up in a Tahrir Square protest. The female lead was verbally abused. Here is another analysis of the film from a film critic’s point of view. The film critics found the movie less than compelling, but I found the class and political intersections riveting. The director Yousry Nasrallah has made a documentary, a fiction, and a story of individuals as he says “refusing to be victims of large social issues.” Actually though, that is not quite true of the camel driver Mahmoud.

6 Coming Forth By Day directed by Hala Lotfy

Another film from Egypt Coming Forth by Day is by a new female director Hala Lotfy . She follows a mother and daughter as they carry for their paraplegic husband/father. They lovingly try to feed him and nurse him. The film is excruciating to watch because the pace is very slow, we feel we are in the small house also caring for this helpless man, but the result is a rare glimpse into the struggles of ordinary people. But I couldn’t help feel that the young woman who wandered around Cairo on her own and even spent the night outdoors, was a little unrealistic. In no country would a woman sleep outside without concern for her own safety. In Egypt where we know that women are frequently attacked in public, it seemed all the more improbably.

7 The Attack

Finally The Attack brings us back to the Israel Palestine crisis. The film is an original take on the situation, a wealthy and successful Arab Israeli doctor discovers that his wife is responsible for a suicide bombing. His journey to his own roots in the West Bank and to the reasons for her actions are riveting. The film by Lebanese director Ziad Doueiri based on a novel by Yasim Khadra has been banned in Arab countries as well as in Israel. Both Arabs and Israelis accuse him of favoring the other side. But that is the strength of the movie. We see both sides.

SIFF really outdid itself this year in terms of showing international films with substance. And of course, I am only writing here about a fraction of the total. They had a special grant for the movies from Africa.

The films I saw constituted a virtual Middle Eastern film festival in themselves. Film is a crucial medium for revealing stories beyond the clichés of the news: we meet people of compassion, courage, and tragedy. We can learn a lot about the damage that the US is causing in the world, as well as the toll that power politics takes on both artists and other people by seeing films such as these.

This entry was posted on July 10, 2013 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art in Beirut, Art in War, Art of Democracy, Film, Uncategorized.