“Here is Where We Jump,” El Museo del Barrio’s La Bienal 2013

This astonishing work in El Museo de Barrio’s La Bienal 2013 “Here is Where We Jump” is described as follows:

“The black robe used in this work is called “the Knighthawk.” It is meant to be worn by the security officer within the hierarchy of the Ku Klux Klan. It was purchased online from an anonymous merchant in Upstate New York and then embroidered by a group of undocumented workers in Chinatown, New York. Chinatown is historically known as a neighborhood for counterfeit products as well as a place of employment for immigrants. The total number of stitches adds up to approximately half a million, a number that also represents the significant demographic of undocumented workers currently present in New York City.”

This cross-ethnic work by Ignacio Gonzàlez-Lang immediately provokes us. We see the KKK robe in a gallery focusing on young artists in the “post race” era and we think what is that doing here?? But with the additional information we know we are looking at an act of assuming power over fear. The other surprise is, of course, that we associate the KKK with oppression of African Americans in the South and this is a Museum connected to Spanish Harlem, but Gonzàlez-Lang extends its associations to make it a symbol of ignorant aggressive terror toward any “other.”

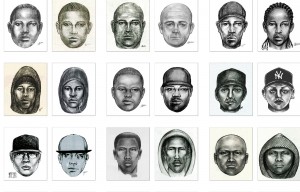

Gonzàlez-Lang’s Guess Who confronts us with our profound racism. The image here is a detail of a large group of police sketches, composite images based on public descriptions of people sought by the police for accused crimes. They are posted online and easily downloaded, which is what the artist did. He has grouped them to demonstrate how similar they can be.

The Bienal ‘s title is taken from one of Aesop’s fables, The Braggart, which challenges someone to jump: “jump here, jump now, here is where you jump.” In this context, it represents the act of a young artist jumping outside of the limitations of traditional art practice to try something radical – La Bienal seeks out emerging artists. The “jumping” theme here has a lot to do with process and experimentation with materials.

Where are we now with ethnicity? Only a few artists could be “labelled” immediately as Latino, as working with icons or topics or even materials that could be matched to the rich material traditions of Latino culture. The work of Alejandro Guzman stands out, with his vividly colored constructions of recycled materials. They are props for his performance art, but stand alone as sculpture (I would have liked to know more about the performance component).

Yes, it is color that seems to be almost missing from the exhibition, that visual feast of color that embraces us when we cross the border into Mexico and continue South. But there is also a strong history of modernism all over Latin America. We forget that what we characterize as “ethnic” is grounded in folk art traditions. Modernism as an elegant international style has been practiced all over Latin America by the educated elite for decades. That is the direction present in the subdued work of much of the exhibition. There are even several artists who are intentionally addressing US modernist abstraction, as in the works of G.T. (Giandomenico Tonatiuh) Pellizzi. In spite of his stunning name, he is painting fields of monochrome color on plywood that intentionally honors a work by Barnett Newman that was slashed some years ago.

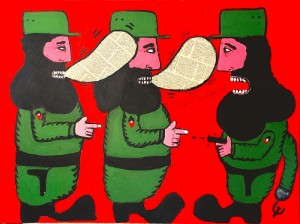

Some of the artists address history: Christopher Rivera’s “Paradise is an Island and So is Hell” looks at imperialism by Theodore Roosevelt in Cuba. Aside from the vintage cartoons, the rest of the installation is experimenting with new materials; for example, implements that appear to be corroded. Are these the debris of capitalist invasions?

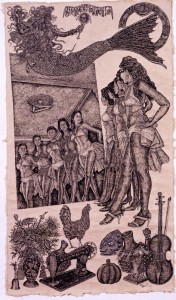

More traditional and straightforward, but impressive are the large ink drawings of Manuel Vega, which engage some familiar iconography of Latina art, although in an original way.

Another artist who taps into a folk art aesthetic, as well as street art are the brightly colored and pointedly explicit, paintings by Cuban born, self- taught artist Bernardo Navarro.

An entirely different type of work by another Cuban- born artist is by Pavel Acosta: he worked with scraps of paint in Havana, out of economic necessity, and because Havana is everywhere full of buildings with peeling paint. So we have a material that is a metaphor.

Acosta scraped the paint off the sheet rock wall in the gallery of the museum and used those scraps to replicate a painting in the museum’s permanent collection (see image below) as a line drawing (the lines are the negative spaces). His tour de force is a reflection of the extensive training that Cuban artists receive, they are technically and conceptually very sophisticated.

The painting in the permanent collection that he replicated by Manuel Macarulla, Goat Song #5: Tumult on George Washington Avenue, 1988 is a carnival scene in Santo Domingo. It indirectly refers to the role of the US in imperialist adventures in Santo Domingo and elsewhere in the title and the Washington Monument in the background ( which actually exists in Santo Domingo)

Accosto’s pale reflection removes the color and makes the subject hard to see, perhaps suggesting that the same shadowy operations are still going on, but more invisibly (or not? has it become only process?)

There is a partnership with artists from Brazil: Jonathan de Andrade uses video to tell us about disappearing history: the loss of Bolivia’s coastline to Chile in a war of the Pacific of 1879-84.

Paula Garcia presents two intriguing performances, in one she is covered in magnets as volunteers attach scrap metal until she looks like a strange monster; in the second, horses, hippos and monkeys emerge in surveillance footage of Oscar Niemeyer’s famous modernist pavilion. As the camera sweeps through the empty pavilion, the animals seem to be repossessing a lifeless space.

The dance performance by Sara Jimenez and Katilynn Redell is intentionally avoiding sexual and ethnic markers. Their movements inside the stretchy bright red fabric are visually stunning as the shape seems to ooze and stretch over a rock. Their work intersects with modern dance as well as modern art and performance art, but in exploring the hybrid body, they become actually the modern body with a few new possibilities.

Julia San Martin paintings evoke the feeling of terror from the period of the dictatorship in Chile through brief figurative references in a canvas that is a black and white semi abstraction. The mood of the work is nostalgic, terrified, and protective. One could say that the house motif is familiar, but here the reduced color and the scale bring the work off.

There are many other works in the Bienal: it is designed to encourage young artists, and in that goal we can see why the works sometimes have unrealized potential.

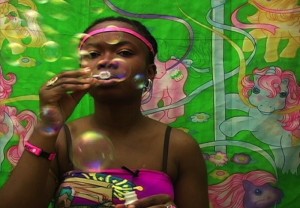

The tour de force video by damali abrams imitating self help shows presents us with the young artist for 365 days taking on a multitude of identities and issues. The problem is that we mainly notice she is really young and her topics are a lot about her appearance, clothes, and other trivial issues. Of course that is what self help shows are about , so she is drawing that large.

Another media action is Eric Ramos Guerrero Cortez Killer Cutz Radio The pirate radio station is taking off from Columbia University’s frequency in the middle of the night. I haven’t actually heard the broadcast, but any absconding with hegemonic communication seems like a good idea.

Finally there is Hector Arce-Espasas Welcome to Paradise. THis piece to me had that valuable quality, the synthesis of provocative materials and content. We see the unshapely vessels ( ceramic but they simulate silver pineapples) on a pile of crates. The assymetrical stack is unstable. Silver and pineapple, are immediate signifiers of colonialism, exploitation. Arce-Espasas captures that idea without any narrative.

So ethnicity, like sexuality and gender, is now difficult to mark, to identify, to characterize. Everything is about hybridity. At least in the exhibition. Modernism is still wielding its powerful force of materials and aesthetics as an end in themselves. It is important to think about the fact that artists have spent the last generation escaping the limitations of modernism. We seem to have come full circle.

Almost all of these artists are living in the US, but their family origin and often their birth place is in cities all over Central and Latin America, from many many different cultures; what most of them share is the act of immigration to the US, yet there is nowhere a reference to that in the work selected, with the single exception of Ignacio Gonzalez-Lang mentioned above.

Given the current rabid racism and prejudice against immigrants sweeping the country, I was disappointed not to find that some of these young artists engage that issue. Focusing on materials is a class issue, really, modernist abstraction and emphasis on process are both long standing approaches in Latin American art among the wealthy elite. The immigrants coming across to work in the US out of economic desperation are not stopping to focus on abstraction and materials. They are lucky if they can get a job.

Many of these artists, regardless of their own personal trajectories or the nightmare politics that they left behind in their own countries and in the US today, have taken on the privileged position of an apolitical modernism. We have no idea how they came to this safe landing, but certainly the emphasis on process in the interpretation of the theme “Here is where we jump,” encouraged that direction. Ironically, it could have led to something completely different, thinking about fence crossings. But perhaps NYC is too far from Mexico to be thinking about that possibility.

This entry was posted on September 21, 2013 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Ethnicity, Latino Art, Uncategorized.