Obsessions in Venice

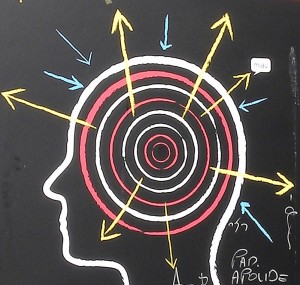

Here is the logo for the Venice Biennale.

Small blue arrows going in and big yellow arrows going out of a brain represented by red and white concentric circles.

I can testify that this Biennial definately gave everyone a lot of penetrating arrows going in and out of our brains. We all know that artists are obsessive, but this exhibition showed that trait carried completely over the top, and with astonishing and mind stretching results.

Massimilano Gioni’s point of departure for Il Palazzo Encyclopedico/The Encyclopedic Palace, the vast central exhibition at the 2013 Venice Biennale, is his concern that the ability to imagine is threatened in today’s culture of digital media, instant news and communication.

His exhibition is named after the eponymous “Encyclopedic Palace of the World ” by Marino Auriti. While his structure was never built, Auriti imagined it as a place to order all the knowledge of the world in a single place. This is the type of megalomania and obsession that Gioni has located in the artists he selected to be shown in his own encyclopedia of the imagination. Most of the artists are working in the twentieth century.

Gioni is challenging contemporary artists and thinkers with the question: Is it still possible in the twenty first century to pursue this level of obsessive creativity?

An encyclopedia of knowledge stems from Diderot and the age of Enlightenment (also the age of colonization), when Europe thought it could organize the world better than it could organize itself:

“Indeed, the purpose of an encyclopedia is to collect knowledge disseminated around the globe; to set forth its general system to the men with whom we live, and transmit it to those who will come after us, so that the work of preceding centuries will not become useless to the centuries to come; and so that our offspring, becoming better instructed, will at the same time become more virtuous and happy, and that we should not die without having rendered a service to the human race in the future years to come.” —Diderot Vol. 5 (1755)

Such utopian paternalism is obsolete today (although political leaders and many others, are not necessarily aware of that). But Gioni has assembled hundreds of works by artists with encyclopedic bodies of work based on personal obsessions. He creates striking intersections between contemporary and historic art, famous and obscure, highly trained modernists and self-taught outsiders.

The artist, Rosella Biscotti, recorded the dreams of the women detained in a prison on Giudecca, evoked by this structure, dreams are the only means of escape for the inmates of this detention facility designed for life imprisonment.

Held in a psychiatric hospital for five decades, Arthur Bispo do Rosario created 800 tapestries, sculptures, and lavish ceremonial garments in prepartion for Judgement Day. Made from discarded materials in the hospital such as sheets and uniforms

The exhibition included art by the insane, the imprisoned, the displaced, the autistic, the deaf, the blind, people who exist outside of “normal” society, outside of the usual social structures, who are under great physical restraints. But all the artists, whether outsiders or not, had one common characteristic: they are obsessively possessed by images that they pour out in hundreds of drawings, sculptures, paintings, and journals.

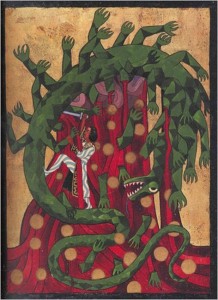

These artists embrace vast amounts of knowledge ranging from the esoteric to the minutiae of science; they meditate on the supernatural, and try to depict their own hallucinations, to visually capture their own nightmares and dreams; they probe the microcosm, the inner workings of the body or the mind itself; they produce detailed observations about the natural world, or invent a new language. They explore memory, recover history or reinvent mythology. They create new cosmologies. They reimagine nature.

Is this not the definition of creativity: the act of moving outside the known, the easy, the predictable, the understood, to embrace another vision of the world?

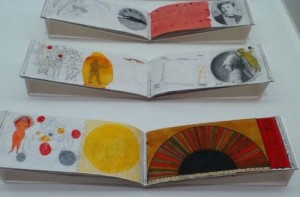

Few artists survive into the historical record to be even acknowledged, much less respected. Yet, artists persist in believing in themselves by creating thousands of works of art, dozens of written pages. They construct their own reality as a way to order the universe in any way that they decide whether it is in room size installations or tiny journals kept for dozens of years.

From my perspective as a writer, I was most excited by systematically maintained journals that respond to intense writers like Jorge Luis Borges (Christiana Soulou), so intimate they are hard to reproduce,

and Franz Kafka (Jose Antonio Suárez Londoño)

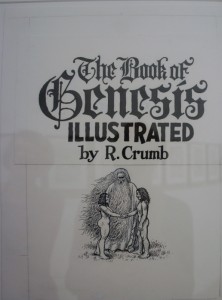

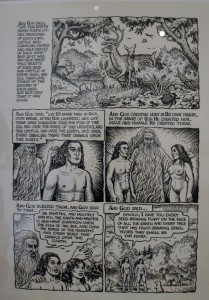

or even the Bible (Robert Crumb).

Carl Jung, obviously someone who actually succeeded in changing the way we think in a profound way, is the first artist in the main venue in the Giardini. His concept of the “collective unconscious,” the idea that all cultures share similar mythic impulses, is still an exciting idea. The fact that he spent years illustrating his own hallucinations as a means to reconnect to a mythic past that he felt had been lost in the twentieth century, demonstrates obsessive creative thinking as well as an unwavering faith in himself. His stunning watercolors, illustrations for his Red Book, filled a room with their glowing colors and eccentric imagery.

Now, you might ask, what does all this have to do with art and politics, the theme of my blog. Well, in my opinion, it is a political challenge to the dominant culture to celebrate imagination, to explore reordering what we know through dreams and hallucinations. As we are increasingly consumed by material goods in the here and now, as we are destroying the planet because the extractive industries cannot imagine an alternative, as we continue to wage war just like tribes and clans from centuries ago, as we continue to allow a few people to exploit the many, all of these calamities are the result of a lack of willingness to risk a more imaginative solution.

Imagination and creative thinking is threatening to the status quo. That is why music and art are considered frills to be eliminated from schools. Much better to have an ill informed public dosed into submission by the drug industry and fed shallow pieces of information. Rapidly disappearing are the obsessive outsider artists and home hobbyists of the past. Today we have instead, obsessive digital game players.

Enter the artists of the Venice Biennale as inspiring examples of artists who explore, think, read, record, and speculate about the world. That is a radical act in itself.

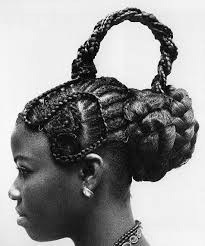

In the first Arsenale gallery the photographs of J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere fill the walls around the model of the Encyclopedic Palace at the center. Ojikere took 1000 photographs of the elaborate hairstyles of Nigerian women, of which only a fraction are on display here. These stunningly elaborate hair styles marked identity, social position, and cultural changes over 40 years starting in the late 1960s, an exuberant period of independence. So his project signifies a larger political reality, at the same time that it records timeless actions with significance rooted in tradition. Of course, it would have been more meaningful if each hairstyle had been explained in that context, rather than presented as simply a sequence of forms.

In the next gallery, the sculpture of Roberto Cuoghi stands as the dialectic opposite to the rationally constructed palace by Auriti: its bulging organic shape is unstable and incomprehensible. It was created not from stone but from a 3-D printer, and it suggests the collapse of lucidity and the world order as we know it; its bulk stretching into space as a strange new life form.

Such a dialectic appears repeatedly in the exhibition, the rational and irrational, the geometric and the amorphously organic.

Danh Vo’s installation combines references to an imposed religion (that is in itself irrational), and its rational artifacts, with irrational acts of cultural destruction. He has brought to Venice the wooden framework of a colonial church (from Hoang Ly, Thai Binh province Vietnam) that combines sturdy vertical columns inspired by European architecture with Vietnamese decorative elements.

The installation also includes evocative brown velvet wall hangings which formerly held icons and crosses, but now show only random darkened shapes, pentimenti, of those sacred objects.

A former icon crammed (we know not when or why) in a carnation milk box appears to be a torso of a saint, now become an inanimate but haunting piece of wood that yet speaks of its past identity. The objects and absence of objects hold the echoes of an imposed religion, a practiced religion, a past that has been destroyed, a lost culture that preceded both the recent past in Vietnam and colonization. But the whole is much more than the sum of its parts as we walk through the installation. We feel the whispers of old practices and the shouts of recent devastation in these quiet understated objects.

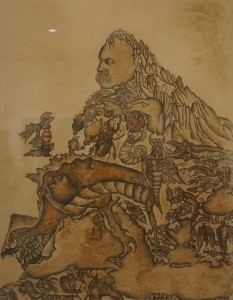

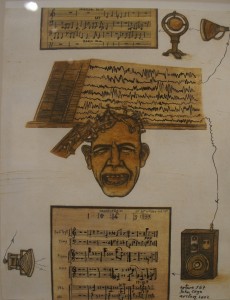

Repetition of infinite variation within a consistent format appears frequently in the Encyclopedic Palace. Yüksel Arslan, for example, creates all his drawings with paint made of blood, urine, egg whites, bone marrow, potash and honey, giving them a consistent brownish hue that belies the vast and complex details of his work.The homemade medium combined with the detailed exploration of the body compels us to look closely and plunge into his world. In the series here he outlines various mental and physical conditions such as cancer and schizophrenia,

creates a map of Europe out of crustacea and pays homage to John Cage, just for starters.

The esoteric and the spiritual was everywhere, starting with the theosophy movement in the late nineteenth and turn of the twentieth century. Of the artists who actually participated only a few were included – Hilda af Klimt and Rudolf Steiner for example. Steiner broke away to form his own Anthroposophy and af Klimt’s best work came when she liberated herself from the group (and Steiner’s) influence. In the early twentieth century such artists as Kandinsky, Malevich, and Mondrian ( not included here) were crucial advocates.

Notably, theosophy combined Eastern and Western esoteric traditions and that thread of a European view of Eastern mysticism continues in Venice. The grand desire to re order and rethink cosmology is a popular obsession.

The European Surrealists with their embrace of the irrational, are an obvious reference point. The most striking example is the work by Ed Adkins using footage of Andre Breton’s collections that have now been dispersed. As we see the camera panning over an astonishing combination of modern art by fellow surrealists, African artifacts, and a fascinating collection of books, we feel we are looking directly into Breton’s mind. The only surrealist paintings in the Encyclopedic Palace are by Dorothea Tanning, perhaps because she died in 2012 and she is a link (with Max Ernst from the early 1940s) between early surrealists and later artists.

As a person who believes in assertive action in the public arena, I have trouble with mysticism and esoteric phenomenon. I have always tended to dismiss the entire sphere as trickery and delusion. On the other hand, the artists represented here have produced amazing art spurred by their esoteric beliefs, their synthesis of spiritual ideas.

Such a crucial historical figure as Rudolf Steiner

juxtaposed to contemporary artists like the dancer/movement artist Tino Seghal, here with very young Italian children mesmorized by his performance.

I was surprised to see my old friend, the ceramic artist Ron Nagle, included in this particular Encyclopedia. Nagle is a musician as well as a stunning artist. I have always admired his small geometric works in clay for their subtle color. The fact that here he is responding to his dreams is a real change of pace. But these works are still small, intense and subtle. Only now they are also unpredictable.

Ron Nagle

Another important aspect of the mind is memory and its physical manifestation, memorials; many works emphasized that including the huge mosaic 9-11 memorial by Jack Whitten.

There were dozens of other riveting artists. It is impossible to really review this show and do it justice. So lets return to the theme: can such obsessive creativity still happen in the 21st century?

A possible answer is posed by Ryan Trecartin. Difficult to watch, his videos (in collaboration with Lizzie Fitch) are based on the aesthetics of reality tv, sports, game shows and You Tube videos. Trecartin creates these works, their sets, their costumes, and he and his friends act in them, exaggerating their ghastly aesthetics as well as their sadism, the blend of reality and fantasy (we can no longer distinguish them). He nails the vacuity and cruelty of today’s online culture. It was frightening to see young children avidly watching them. But, undeniably, this work was crucial to the exhibition’s premise. Juxtaposed to the virtual retrospective of the giant of avant garde film, Stan Van der Beek, made the question of where are we going all the more evident.

Gioni displays the obsessions of artists to remake the world, to rethink spirituality, to order knowledge. He combines in a single overwhelming exhibition, the extent of artistic obsession and aspiration in a way I have never seen before. He celebrates the enormous output of artists who follow their creative passions.

Moving forward, with the obsolescence of all of the material culture from centuries of creativity, with books used as material for sculptures, rather than as documents of knowledge, where do we go from here?

I do not agree that imagination is threatened with extinction. Today, it is possible, even necessary, to imagine a new future. Even in the midst of our flood of consumerism, ossified political thinking, and innane digitized visual culture, many artists are doing just that. They are often also perceived as outsiders to the capitalist world, they are seniors, they are people of indigenous cultures, they are “dreamers”(term for undocumented youth brought to US as children). I would like to see those committed visual artists in the next Biennial. Like the artists from the last century, they too are taking on the world, they are taking on the tired belief systems of the past, and creating new synthesis, new ideas, or exposing the bankruptcy of old ones.

For examples you can read any of the other posts on my blog or my book Art and Politics Now, Cultural Activism in a Time of Crisis

This entry was posted on November 2, 2013 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art of Democracy, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized, Venice, Venice Biennale.