West of the Caspian Sea “Love Me Love Me Not” Azerbaijan in Venice

On the West side of the Caspian Sea, in Azerbaijan, Baku is the showpiece of contemporary life in the country. “Love Me, Love Me Not, Contemporary Art from Azerbaijan and its Neighbors” was commissioned by Yarat, a contemporary art space in Baku that sponsors extensive exhibitions and programming. Yarat is led by the youthful and talented Aida Mahmudova.

Baku has been a prosperous oil city since the early 19th century and that oil was a prize much sought after by both Stalin and Hitler during World War Il, and by superpowers ever since. A massive pipeline was completed in 2005 carrying oil from Baku through Georgia to the Turkish port of Ceyhan. The pipeline was of course loaded with international power politics. It couldn’t go through Iran because the US said no, it couldn’t go through Armenia because of long standing tensions, so it had to go UPHILL through Georgia. Revenues from the pipeline have been enormous as has the impact on local ecologies and communities as presented in Ursula Biemann’s video Black Sea Files.

The area around Baku is literally soaked in oil and has been for many decades. Some of the local people see the oil as healing or sacred ( in the spirit of Zoroastrianism water and fire are sources of ritual purity). The reality is that the area is full of toxic wastes.

Some of the huge oil revenues have found their way into support for contemporary culture. The seventeen artists in “Love Me, Love Me Not,” primarily come from Iran and Azerbaijan, but also from Georgia (Iliko Zautashvili) and Turkey (Kutluğ Ataman). Iran has more Azeris than Azerbaijan, but Azerbaijan and Iran are also long time rivals, so their coming together in Venice is significant.

Dina Nasser-Khadavi, a curator originally from Iran, declares that this region is not part of the so-called “Middle East.” It is also not simply Trans Caucasian. Azerbaijan and its neighbors have a common history as part of the Ottoman, Persian and Russian empires.

Nasser-Khadavi declares “this show does not take a political stand, nor is it aimed at making a statement.” Obviously this is one of those disclaimers that assumes that politics can be removed from the art and the exhibition just by saying so. But the statement itself also reflects the close connections between the government and support of contemporary culture. Obviously,criticism of the government is not going to happen in this exhibition.

The exhibition is intended to enable Euro centric viewers to correct their ignorance about this region, an ignorance based on,among other factors, media-generated stereotypes. Media simplifications are referred to in Nasser-Khadavi’s essay with the example of Ben Affleck’s film Argo.about the 1979 Iran hostage crisis. Media information is a deliberate political campaign, so countering it with complexity, as this exhibition strives to do, is clearly a political act. Under the guise of aesthetics, the works shown here subvert clichés.

The title of the pavilion, aside from reference to the familiar children’s game, was adapted from a work by the group Slavs and Tartars, Love Me, Love Me Not/ Changed Names, 2010, which refers to the changing names of cities in the region. As they articulately state, “[it] celebrates the mulitilingual, carnivalesque complexity readily eclipsed today by nationalist struggles for simplicity and permanence.”

Indeed the complexity of language in this region is mind boggling.

As this region changed imperial affiliations over the course of a century, the written script changed as well, from Arabic, to Latinized Turkish, to Cyrillic and now Latin. Various former Soviet republics have followed different paths following independence from the Soviet Union. In Azerbaijan, speaking Russian is still considered a mark of the elite but written Azeri is Latinized Turkic, with its vocabulary, grammar and structure based in ancient Turkic , a different language branch than the modern Turkish of Turkey.

Lost in Translation… This Too Shall Pass, is a projection piece by Rashad Alakbarov in which words written in all of these scripts dangle from the ceiling in mobiles that turn in response to the air and

appear and disappear according their relationship to the light source.

Mahmoud Bakhshi’s Mother of Nation, directly refers to oil and its mixed role as source of wealth and source of destruction, in a sculpture that resembles a ziggurat built of gold blocks. At the top is a baby pacifier. This sardonic reference by an Iranian living outside of Iran, certainly has several layers of meaning.

The Tree of Wishes by Rashad Babyev refers to consumerism as much as ritual by its use of designer silk scarves instead of the rags of traditional wishing trees.

Ali Hasanov’s Masters, is a pile of traditional brooms made of bundled twigs, traditionally used for cleaning, now discarded, become a reference to the role of simple functions performed by ordinary people that are being ignored.

On a similar theme, the well known Kutluğ Ataman provided a section of his large scale multimedia installation, Mesopotamian Dramaturgies. Here it features a column of forty two television sets with close ups of dozens of villagers from Eastern Anatolia, all silently standing against a wall of old stone or concrete. The wall is the only signifier of where these people are living, but their silent gaze looks back at us, forcing us to see them as individuals. They are the people on the ground, affected by larger geopolitical forces ( also addressed in Ursula Biemann’s work)

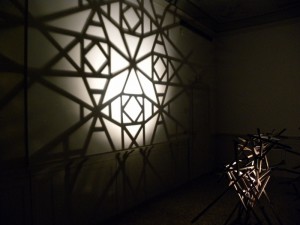

Farid Rasulov’s creates traditional stained glass designs embedded in chunks of concrete to address the juxtaposition of the traditional and the contemporary.( see also image at top of post). It is a direct reference to the city of Baku, which juxtaposes brutal modern and post modern skyscrapers with preservation of historic sections. The historic buildings in Baku become a type of fantasy of the past, accessible for tourism like a Disneyland, in the midst of the skyscrapers.

Orkhan Huseynov collects interviews from his peer group about “Bruce Lye”‘s films. The films imported to Azerbaijan were actually imitations, by an impersonator, Bruce Lee, who was imitating Bruce Li. The entire sequence plays with the idea of authenticity, fantasy, and shared cultural experiences. We sit in period furniture as we look at the videos of these young men recalling what the films meant to them, now knowing it was all an imitation.

Fashad Moshiri creates carpets with reproductions of the covers of contemporary fashion, film, and gossip magazines, also a reflection of the cultural moment. In his case, he is crossing between the lowest common denominator of magazines, and the high art of silk carpet weaving. Here he creates a “kiosk” of hundreds of carpet/magazines, also playing with idea of consumerism, media stereotypes, and tradition.

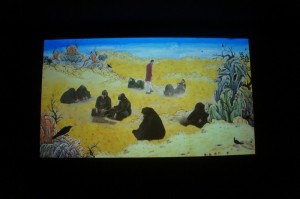

“King of Black” by Shoja Azari brings together poetry, film and miniature painting. The story follows from one section of

“Haft Paykar” (Seven Beauties) a twelfth century poem by the Azerbaijani Poet Nizami. the mythic story follows the King of Black as he searches for the reason a city is in constant mourning. It extols the virtue of patience. The animation is lush: the star walks through the elaborate landscapes of miniature painting.

Azari is Iranian, but as her name indicates she is ethnically Azari. The metaphor she has chosen may be a subtle reference to the Northern Iran area separated from its Azari roots.

All the artwork addresses various traditional cultural practices, overlaid with pointed references to the contemporary world. The question of the role of “craft” traditions in contemporary Azerbaijan permeated many of the works.

The celebration and reinvention of traditional craft is central to works like Recycled by Aida Mahmudova, which reuses ornamental window grates, or Afruz Amighi’s woven plastic and plexiglass with motifs from traditional Venetian glass and Islamic brass (on the left of the image above). Faig Ahmed takes off from carpet weaving to create an abstract design in thread.

Similar concerns appear in the official Azerbaijan pavilion

“Ornamentation,” which includes two of the same artists, Rashad Alakbarov and Farid Rasulov whose imitation carpet pattern work opens the installation(above)

The pavilion is sponsored by the Hedar Aliyev Foundation in Azerbaijan, the Foundation of the wife of the President. It simply celebrates the fact that the “history of the country is encrypted in its carpets, stone sculpture and embroidery.” The statement mentions the interweaving of “Zoroastrianism, Christianity, and ancient art traditions.” (and Islamic?) and suggests that these motifs are the real alphabet of Azerbaijan as contemporary artists draw on them to create contemporary conceptual art.

“Ornamentation” emphasizes the rich craft traditions of Azerbaijan and nearby areas, traditions that have passed through many changes and date back many centuries ( way before all of those empires). Crafts were banned during the Soviet era as bourgeois. Now they are co- opted for nationalism and tourism. But those deeply held traditions are also a rich source for this provocative group of contemporary artists.

It is a straightforward idea that is easy to understand in the rush of Venice Biennial pavilions. But the visual and intellectual impact of the pavilion, compared to “Love Me Love Me Not”, is more haphazard.

Alakbarov’s wonderful sculpture stands out: it becomes a readable pattern on the wall when a light is shined through it at just the right angle. It is an immediately understandable work, giving us the insight of the fugitive nature of material reality.

The Yarat pavilion goes further, not only geographically, but also conceptually, arguing for layers of meaning that include hybridity, nostalgia, memory, and the role of culture in general. As regards the geographical concept, I have not discussed the Russian and Georgian artists here, who touch on these themes as well.

But one of the wonderful aspects of the Venice Biennale is that a region that is so distant geographically from Europe and the US is brought up close for us to think about and reflect on. It is fortunate that the government of Baku and its urban elites have the wealth, intellect, and inclination to support contemporary culture.

From that patronage, we cannot expect to see art about the dark underbelly of Azerbaijan, but these exhibitions present some intriguing artists, as well as information about a major center of contemporary art in Baku.

This entry was posted on December 10, 2013 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Venice, Venice Biennale.