ANTONI TÀPIES 1923 – 2012

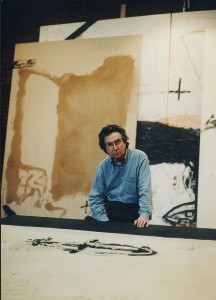

In honor of the New Year 2014 I give you Antoni Tàpies, one of the outstanding twentieth century artists who engaged both profound concerns about the state of the world, and corresponding boldness in exploring aesthetics and material as a way to connect to those concerns. In Part I, I analyze an exhibition in Venice.

In Part II, as a New Year’s present to my readers, I have included the section of my book Art and Politics Now in which I write about Tàpies. That makes this post a bit long.

PART I “Lo Sguardo dell’Artista,” Museo Fortuny, Venice Fall 2013

“Franco wanted to show Spain he was tolerant, so he allowed modern art- I had to walk a fine line to not allow myself to be used.”

Thus speaks Antoni Tàpies in “Lo Sguardo dell’ Artista (The eye of the artist) at the Museo Fortuny in Venice. More than an exhibition, “Lo Sguardo” is an act of love from his friends to honor him in the year after his death. It includes two films, many major art works by the artist, selections from his wide ranging personal art collection, never before exhibited, works by his friends, and even personal pieces of furniture.

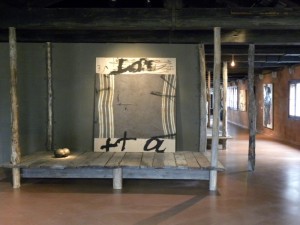

Each floor of the large palazzo had a different mood. On the ground floor was a large simple space with big work, as well as a large sculpture by Anthony Caro, in an adjoining room.

The first landing had a rough wooden floor that changed the atmosphere from gallery to unpredictable exploration.

We were confronted with an intense African sculpture from his collection juxtaposed to a painting and a single sculpture. They spoke to each other across the room.

The next floor is the official Museo Fortuny that displays the fashion designs of Mariano Fortuny. He created stage designs and fashion in collaboration with his wife. Included in the collection are Chinese paintings and robes, stage sets, wooden dummies, and memorabilia. Inserted into this array, without labels, are such works as a painting by Picasso, Gudea in marble, Tàpies Book 1 Libre 1987. In a small case on successive shelves, arranged by the curators, include a coat hanger, copper pot, bronze cross, painting on concrete, screwdriver, spatula (for plaster), scrolls, shell, leather, cat/tiger emerging from granite, stone tied with leather. The mixture of dissimilar objects created a rough conversation, disrupting our equilibrium as viewers and opening off beat aesthetic connections.

A heartfelt statement by Antone Ueng is nearby:

“I urge viewers who struggle to understand Tàpies art not to look for explanations. If they look carefully and that is all if they are open and allow themselves to be possessed by what refuses to be classified, the the painting will find its way through, by stealth. And one day unexpectedly the core of our soul will be swept away like the walls of Jericho and a pleasure produced by the gaining of recognition will be obtained. “

In a dark side room a dazzling red painting by Gutai artist Kahuo Shigako jumps off the wall, the paint so thick that it looks like smeared blood . Tàpies hung the Shigako painting at the entrance of his home, telling visitors exactly what to expect from him.

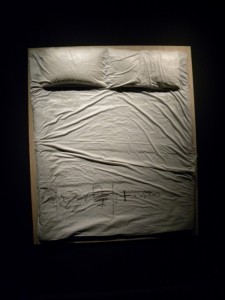

In another small room is Tàpies llit 2009, and a Chinese Buddha sculpture (Suei Dynasty, 6th century) that he had in his bedroom, an intimate Miro and Max Ernst’s Fort Bleu. The music playing is by Giacinto Scelsi – “Xnoybis” – performed by Vincent Royer on two strings. James Turrell’s glowing light installation, Red Shift has another room to itself. These are meditative experiences. The Bed makes an intriguing comparison to the famous Rauschenberg bed. Here we feel a restless sleep, a hidden anguish, a bed that invokes private moments for a man who felt the oppressions of the world so deeply.

The main rooms of this floor create a textured intersection of Fortuny and Tàpies, fashion and desire, juxtaposed to the deep material metaphors of Tàpies that speak of oppression. But in this display the textures, intimacy, and cross references foreground spirituality, an important dimension of Tàpies personal collections and private life.

On the second floor a large open room with walls bearing plaster pentimenti creates an open, but slightly desolate, sensation, with the widely spaced Despertar Sobtat 2006 and Gran Tors 1996 near to Gunther Uecker Trees and Nails a Tribute to Tapies, 2008 – 2013 (center) and a Jain seated sculpture (foreground). A film on this floor speaks of Catalans identifying with Tàpies in their religious and political resistance to Franco.

The entire top floor is devoted to an installation “Wabi Inspirations” conceived by architects Axel Vervoodt and Tasuro Mik, explained as follows

“ Towards the end of his life Tàpies developed a heightened interest in Eastern culture, a concern which increasingly became a fundamental philosophical influence on his work because of its emphasis on what is material, the identity between man and nature and a rejection of the dualism of our society. In this ‘labyrinth of silence’ labyrinth of sacred proportions inspired by Eastern and Western culture are several “tokonomas” four outside and four inside. Toko means platform “ ma” framed emptiness, made from humble materials as Venetian bricolet, cardboard, painted with earth from the lagoon. I tried to create a dialogue between the most silent and serene works by Tapies related to the great masters of calligraphy and anonymous objects made by nature.”

A small work by Kandinsky points to the interior labyrinth: as we walked through the semi dark we encountered a score by John Cage, then in the deepest interior there was a Toraja Funerary door Indonesia and Grans Vertical.

It was a temple.

As a way of coming back to reality, near the exit was access to Sudharu Horio’s 21 meter pole resting on a water mattres that rose from bottom to top of the building in an inner courtyard. I stood on the water mattress without my shoes and felt the instability of the base as well as the cold of the water.

PART II Excerpt from Art and Politics Now, Cultural Activism in a Time of Crisis (available from this website). I am talking about his work here from a political perspective. The “Sguardo” was dominantly aesthetic.

In Art and Politics Now, Tàpies is the first artist in Chapter 3 “Resisting Police States:” my discussion focuses on the connection of his work to political protest as well as to the continuum of political art:

“By way of acknowledging that all atrocities committed during warfare are one and the same, regardless of which war or which century, this chapter begins with the abstract work of the Catalan old master, Antoni Tàpies. His chilling metaphors of abuse and suffering first emerged in the years after Franco, allied with the Nazis and other forces of fascism, emerged victorious in the Spanish Civil War, and brutally ruled Spain.

“Antoni Tàpies provides a direct connection between the mid-twentieth century and the present. In spite of Tàpies’s position as an established “old master” of twentieth-century art, he disrupts the so-called “heroic” critical interpretation of abstract expressionism with disturbing references to pain and oppression. In a Tàpies’ exhibition, no matter how august the setting, the blunt physicality of the materials and the rough gouged surfaces are a call to arms—a spirit working in opposition to the status quo. A huge pounding of physical form deeply penetrates our consciousness. A ceramic foot, head, torso, arm, or body fragment emerges from chunks of earth, confronting us with its tortured history.

Tàpies’s Catalonian roots help explain his ferocious resistance to oppression. As a teenager during the 1930s, Tàpies worked for the democratic government of Catalonia to which his father was a legal advisor. The Spanish Civil War which broke out in 1936 abruptly ended Catalonian independence. The fall of the Socialist central government of Spain, to Franco in 1939, and the crushing of the autonomy of Catalonia deeply affected him. Franco killed hundreds of thousands of resistance fighters in the early 1940s; he sent many others into internment camps or forced labor. The police repressed Communists and trade unionists; Catholicism was the only sanctioned religion. Castilian Spanish was the only legal language. The government censored writers, artists, and other intellectuals and threatened them with imprisonment. While the atmosphere has radically changed in Spain since those years, Tàpies continues to address political oppression and human rights abuses, such as torture, in his art. His original experience is now transposed into a statement about our contemporary world.

In addition to political oppression, Tàpies, like many artists in the 1940s, was deeply affected by the exploding of the Atomic Bomb in Nagasaki and Hiroshima—leading to the final stage of massive death and destruction at the end of World War II. As one writer has suggested: “Tàpies shared a general sensibility which affected artists on both sides of the Atlantic . . . an interest in matter—earth, dust, atoms, and particles—which took the shape of the use of materials foreign to academic artistic expression and experiments with new techniques. . . .”

Llit Marro/Brown Bed (1960), resembles a flayed skin or bandages; a bulge and hollow near the bottom is dug out, as though someone is lost in this darkness, trying to escape with barely a foothold or handhold. In Gris, taronja, rosa/Grey, Orange, Pink (1967), Tàpies marks blunt lines into a thick scarred drab grey surface; the canvas appears to be under attack, and the orange is a swipe more than a stroke, as though created desperately. Sand bulges off the caked surface in awkward shapes; nothing is comfortable. In Forma negra sobre quadrat gris/Black Form on Grey Square (1960), a head seems trapped in the greyness or buried under it. Matèria Rosada,/Rose Matter (1991), suggests the decay of a body.

His assemblages provoke us as metaphors as well as facts. In Pantalons sobre bastido/Trousers on stretcher (1971) a pair of rough workman’s pants caked with grey paint hangs upside down on a canvas stretcher; the stretcher becomes a type of scaffolding. The upside-down pants recall Goya’s etching of a man being castrated upside down in the Disasters of War, and the crotch of the pants is indeed cut open here as though castration has already happened.

Tàpies’s ceramic work is equally forceful. He savagely pierced the larger-than-human scale sculpture of a foot, Pie/Foot (1991), with metal tools, creating an image of torture that corresponds all too immediately with the willful violations of the human body in prison camps of so-called “enemy combatants.” The truncated foot can also be read as a reference to a talisman, or even to a Christian relic—from an unknown and ordinary worker. His work emphasizes humble forms, objects, body parts, and materials. In the ceramics he makes or re-uses a bathtub, a door, a bed, a wall, a head, a skull, a torso, an arm, a coffin, a sock. A cross (which can also be read as a plus sign or the “t” of the artist’s name), numbers, or floating symbols are embedded, cut out, incised, or even hacked into these rough surfaces.

Tàpies once said, “What we call reality is not reality. When for example, I draw a head, I quickly feel the need to destroy, rub it out, because I have only managed to grasp its external appearance, when what really concerns me is what is hidden behind that visible form.”

At the same time, he is transforming basic matter into something more charged, more energized. As one author explains, “In Tàpies’s work magic and mimesis have a common origin which refers directly to its ‘Catalan spirit’: the tradition of medieval alchemy and mysticism.” But what appears as energy in his art is not an heroic gesture. It is rather, a heavy stroke, a trudging movement, a difficult act, an act that is rubbed out and destroyed and re-enacted. Likewise, alchemy is not a private conversation, a form of masturbation or secret domination through magic. This alchemy of humble materials—like a corrugated tin shop door, workman’s pants, straw, or dirt, is about ordinary human suffering, survival and transformation. Tàpies’s walls (always more than a literal or metaphorical surface) are walls of suppression that can be survived, can be marked, but cannot be avoided. He seeks “matter in a state of constant movement and change, a state that stands in opposition to the fragmentation and compartmentalization of the contemporary western world. . . . What is important is not these forms, but rather the existence of a being or object undergoing formation or deformation.” Tàpies transforms raw matter into a metaphor for destruction and survival; he connects, in his use of humble materials, not to the Abstract Expressionists, but to the Italian movement of Arte Povera as well as to the Beat artists of San Francisco, such as Jay De Feo and Wally Hedrick. His work reminds us of past atrocities, even as it speaks directly to our contemporary crisis of crimes against humanity.

This entry was posted on January 3, 2014 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art in War, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.