The Tate Modern “A Chronicle of Interventions” Spring 2014

Group Material, Timeline: A Chronicle of US Intervention in Central and Latin America 1984 installation photograph by Dorothy Zeidman

“If we can simply witness the destruction of another culture, we are sacrificing our own culture. Anyone who has ever protested repression anywhere should consider the responsibility to defend the culture and the rights of the Central American People.” “Artists Call Against US Intervention in Central America” January 1983.

While in London at the Tate Modern, tucked into a small “project” gallery at the entrance that could easily be overlooked, was an exhibition with the title “A Chronicle of Interventions.” The exhibition was a collaboration with the TEOR/éTica space in Costa Rica.

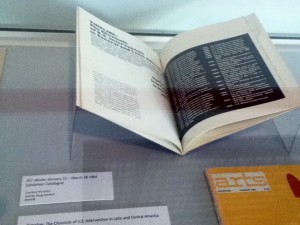

In the first gallery, Doug Ashford and Julie Ault, early members of Group Material, curated a partial documentation of the 1984 Timeline: A Chronicle of US Intervention in Central and Latin America 1984. It was first shown at PS 1 recently “converted” (minimally) from a large public school. The installation at the Tate Modern included some of the documents that appeared as part of the installation of the original timeline and a slideshow of the installation.

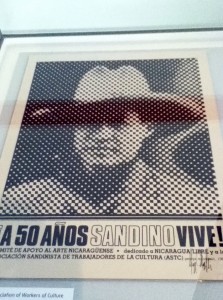

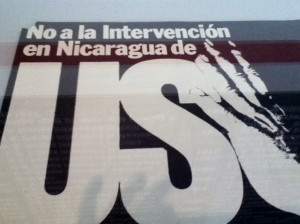

The posters, flyers, flags, articles, paintings, buttons, and artists’ prints had been submitted in response to the “Artists Call Against US Intervention in Central America” issued in January 1983. Installed at the Tate, they lost the aesthetically sophisticated arrangement and immediacy of the original installation. We looked down on them in a box, rather than seeing them in our space.

In the installation views of the original timeline that survive, we see a stunning partnership of numerous art works and ephemera arranged above and below a red line with its black dates (the colors of the avant garde post revolutionary Soviet Art).

At the center of the original Timeline installation was a dramatic red construction, an artifact from a demonstration in DC: a maritime navigation buoy. As described by Claire Grace in an excellent analysis of the timeline in After All Journal, it was a “bright red sculpture that had been brandished a few weeks before the exhibition opened at a public protest in the nation’s capital. Created by Bill Allen, Ann Messner and Barbara Westermann, the sculpture takes the form of a giant maritime navigation buoy. At the demonstration, its bell rang a repeated toll of warning, marking time not metronomically but according to the jostling movements of protestors holding it aloft by the beams at its base.”

At the Tate exhibition, in spite of the museumification of the art works, the intense engagement of the artists comes across clearly. The cross media collaborations of visual artists, critics, writers, musicians, philosophers, poets, street artists compelled us to think about the power of art when creative minds address pressing social issues. Where is that collaboration today? The Occupy movement is an example. Climate Change activists are another. But today we still have a lot of fragmentation of activism, based, unfortunately along racial lines.

In the second part of the exhibition at the Tate, curated by Inti Guerrero and Shoair Mavlian from the organization TEOR/éTicabased in San Jose, Costa Rica, are seven artists using various media. The curators contrast their inclusion of artists “from the region itself” in comparison to the Timeline, which included Latin American artists in exile.

But there are other more obvious distinctions. The artists work as individuals from a theoretical distance, with modernist tropes. We need a lot of explanation in order to understand what a certain photograph or video signifies.

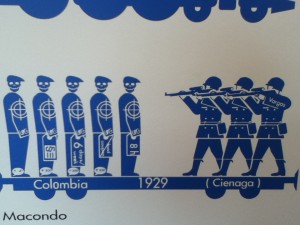

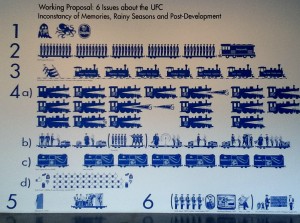

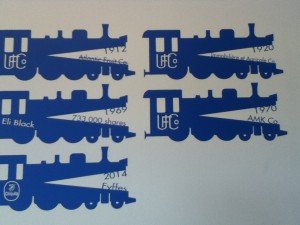

The only exception to that is Andreas Siekmann, whose charts in blue, with iconic and recognizable images, and hard hitting information, clearly tells us about exploitation. (He is German, not “from the region”).

The other artist whose work is straightforward is Regina Galindo, the well known Guatemalan artist who has been protesting through performance and poetry the nightmare of violence in her country. But even her work needed an explanation. The artist stood in the field that was slowly excavated around her. We could interpret it in many ways, until told that it referred to mass graves.

Other artists were esoteric: Michael Stevenson ( from New Zealand) had a lengthy narrative “Introduction to the Theory of Probability” that connected the Shah of Iran in exile in Panama, the presence of Patty Hearst on the same island, and the theory of probability represented through anonymous hands playing solitaire. (The connection was that the Shah’s bodyguard became a mathematician). Oscar Figueroa’s performance piece laid out a 3,275’ line of blue plastic to demarcate the segregation of communities of workers for United Fruit Company (blue plastic was used to protect bananas from pesticides, so the analogy of protecting local elites from imported dark skinned workers).

A piece of blue plastic also hung on the wall of the gallery, a post minimalist object. I wanted more!

The contemporary body builder in the film by Humberto Vélez’s film The Last Builder makes a connection between a contemporary body builder and the African bodies that built the Panama Canal. Oomph. Not particularly provocative. José Castrellón explores what is referred to as “cultural hybridity,” in a parallel of the appearance of indigenous Kuna Tribe members and punk metal bands (I didn’t get this, but maybe with music I would). Finally, there was Naufus Ramirez-Figueroa’s dance of architectural styles, three dancers wearing a style as a costume and gradually shedding it. Pretty hokey.

The overall theme is colonialism, but with the exception of Galindo and Siekmann (his project is ongoing) , there was no reference to what is actually happening on the ground today. It was all theoretical and abstruse.

The huge contrast to the heartfelt work of the 1980s artists who joined the Artists Call was obvious. That is the main distinction between Group Material and contemporary artists selected for the exhibition.

There are plenty of artists in Central America addressing current violence and atrocities. The curators from Costa Rica (itself an exception to the politics of the rest of the region) simply chose to find artists who were exploring the present through a veil of theory and modernism.

I honor Group Material’s remarkable activism in response to the violence in Central America in 1984 and hope it will inspire artists today when that violence is still so obvious.

“If we can simply witness the destruction of another culture, we are sacrificing our own culture. Anyone who has ever protested repression anywhere should consider the responsibility to defend the culture and the rights of the Central American People.” “Artists Call Against US Intervention in Central America” January 1983.

This entry was posted on August 30, 2014 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art in War, Uncategorized.