American Art at the Newly Expanded Tacoma Art Museum

Tacoma Art Museum with detail of Marie Watt, Blanket Stories: Transportation Object, Generous Ones, Trek 2014, Cast bronze.

THE AMERICAN WEST: THE HAUB FAMILY COLLECTION AT THE TACOMA ART MUSEUM

Elk Buffalo, The Monarch of the Plains created in 1900 by Henry Merwin Shrady sets the tone for the exhibition in the new wing of the Tacoma Art Museum, designed by Olson Kundig Architects. Shrady drew his buffalo in a zoo. This monarch of the plains, like so many of the Native leaders depicted in these paintings at this time, was captured and confined.

The mighty buffalo is a frequent subject in the Tacoma Art Museum’s new collection of 295 works of American art by 140 artists acquired by a generous donation from the Haub Family. In a later gallery, we are confronted by the fauve-inspired Buffalo at Sunset by Apache-affiliated artist John Nieto painted in 1996. In between is Frederic Remington’s Conjuring Back the Buffalo of 1889, filled with skulls, which marks the condition of the buffalo at the end of the 19th century: almost extinct as a result of widespread and intentional slaughter.

The effort to exterminate the buffalo failed. They are now not exactly thriving, but numerous. Native peoples also survived attempts to exterminate and assimilate them and to terminate their tribes. Today many aspects of their cultures are being resurrected and reshaped in dialog with the contemporary world. More than that though, as profound speakers and savvy activists, they play a crucial part in contemporary efforts to stop the devastating practices causing climate change.

At the far end of the sculpture gallery (its plentiful natural light carefully controlled by the architects), a conversation begins. Beside a 1978 bronze sculpture of Chief Washakie by Harry Jackson, the words of the Chief spoken exactly one hundred years earlier eloquently state the physical restraints of those years:

“The white man, who possesses this whole vast country from sea to sea, who roams over it at pleasure, and lives where he likes, cannot know the cramp we feel in this little spot…every foot of what you proudly call America, not very long ago belonged to the red man.” —Chief Washakie, 1878

By including this stirring description by Chief Washakie of the nightmares of forced resettlement, Tacoma Art Museum Haub Fellow, Asia Tail, begins the task of reframing the romanticized concepts of the art of the West on display in the Haub Collection. Affiliated with the Cherokee tribe, Tail explained, “The quotations are just the beginning of a project to integrate Native voice and presence in this exhibition.” Four compact interior galleries display a selection of 120 paintings from the Haug collection. The understated design reflects Olson Kundig Architects’ surprising philosophy that art, not the architecture, should dominate at an art museum. The new wing is meant to evoke both a railroad boxcar and a longhouse, two references to the West embedded in Tacoma.

Comments by both Haub Curator of Western American Art Laura F. Fry and native speakers appear beside many of the paintings and sculpture throughout the exhibition.

For Junius Brutus Stearns’s The Meeting of Tecumseh and William Henry Harrison at Vincennes, 1851, Laura Fry focuses on the artist’s love of ancient history: “In creating this fanciful image some 40 years after the Shawnee leader’s confrontation with General William Henry Harrison in 1810, Stearns presented the scene of an American conflict between two epic leaders in the same light as the legendary events of ancient Rome.”

But we also hear from Tecumseh himself “The only way to check and to stop this evil, is for all the red men to unite in claiming a common and equal right to the land. … The white people have no right to take the land from the Indians, because they had it first; it is theirs.”

Wanata (The Charger) Grand Chief of the Cherokee by Charles Bird King purposefully, but with somewhat pathetic results, tries to give Wanata the pose of European “grand manner” portraits. The artist never met Wanata, so he made up the portrait from someone else’s sketch. King was commissioned to paint portraits of the Native leaders who came as delegates to negotiate with the US government in 1821. The idea of a vanishing race was already creating Indian galleries on the East Coast in the 1820s.

Next to Canonicus and the Governor of Plymouth by Albertus del Orient Browere, Tail comments “This painting hints at the long history of conflict between Native American tribes and the US government. Native leaders have continued to fight, long after Canonicus’s time, to protect their people and advocate for their rights. Because of the efforts of our ancestors, millions of Native Americans from hundreds of nations are still here today.” Obviously this is a direct refutation of the prevailing ideology behind the paintings of native leaders in the 19th century, that they were a vanishing race.”

Scott Manning Stevens (Director of Native American Studies at Syracuse University) points out in his catalog essay that including the Northwest in the concept of the West integrates the hundreds of native groups practicing various ways of life. It moves beyond the limited cliché framed by Western movies that focus on cowboys and Indians of the High Plains. The catalog also includes insightful essays by Fry and Peter Hassrick (Director Emeritus and Senior Scholar of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming) as well as color illustrations and discussion of individual artworks.

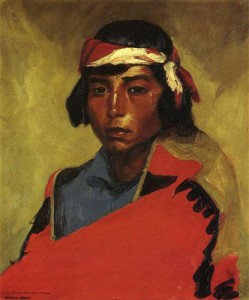

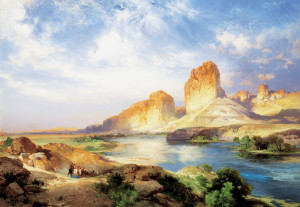

The collection includes many surprises (most of the works have never been exhibited before), including a work by Rosa Bonheur, and paintings by Robert Henri, Thomas Hart Benton, Maynard Dixon, and Taos school artists, as well as examples of landscape painting by such well-known artists as Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran.

Some people I spoke with felt strongly that the museum should work much harder to deconstruct the clichés of the West in the labels and in the organization of the display. I would have liked to see more contemporary native art.

Curator Laura Fry understands the issues. She spoke of complicating given ideas citing, as an example, the multiple racial backgrounds of cowboys. Asia Tail’s project represents an ongoing commitment on the part of the museum to expand native voices.

The museum also commissioned a public sculpture outside the new wing by Seneca artist Marie Watt: Blanket Stories, Transportation Object, Generous Ones and Trek. The artist invited community members to contribute blankets that would be cast in bronze at the Walla Walla Foundry. Each donated blanket has a story that can be accessed on the museum website. It creates a giant relaxed x shape in front of the museum, a concept that could have many meanings.

Clearly, the museum is interested in framing the collection of art of the American West in new discourses. I look forward to hearing about further programming that will introduce new ideas and voices to counter the traditional romantic perspectives in art of the Haub Collection.

This entry was posted on January 16, 2015 and is filed under American Art, art criticism, Western Art.