Delhi Feminist Artist Gogi addresses the 2012 Gang Rape of Nirbhaya

ALTAR FOR NIRBHAYA by Gogi Saroj Pal

“At the heart of Gogi Saroj Pal’s art is the understanding of female complexity” ( Mary-Ann Milford-Lutzker in Gogi Saroj Pal, The feminine unbound, Delhi Art Gallery, 2011)

Gogi Saroj Pal, a radical feminist artist based in Delhi, India has spoken out about the contradictions for women in India for many years. Her most recent series “Altar for Nirbhaya” is dedicated to the 23 year old victim of gang rape in 2012. Nirbhaya, meaning “courageous one” is a pseudonym for the name of the victim. She was raped on a bus in Delhi enabled by a bus driver who drove around the city for over an hour while five men raped her after attacking her boyfriend.

It is a horrifying story. Two weeks later she died. What makes the story all the more upsetting is that she had hoped to provide free medical care to the poor after she finished medical school. Her family is poor, they had worked hard to enable her to get an education.

Her story ignited rage all over the world. But now three years later, we have all stopped thinking about her. Gogi’s paintings remind us vividly of the violence of that attack and the death of the victim. The sickle at the center piece of several works refers to an attribute of Kali, the Goddess of Destruction.

The contradictions for women in India loom larger than any other country in the world. As Gogi has said

“Our mythology is crooked and so is our mentality,” says Pal. “As we celebrate Navaratri [Hindu Festival of Lights in honor of Durga the universal mother], we also kill a girl child, and as we worship goddesses for money, we continue to rape our women.”

Indeed, in India the worship of Durga is a hugely popular festival, Durga is regarded as the universal mother. Goddesses in general prominently figure in Hindu mythology and daily ritual practice: there is Lakshmi, Vishnu’s consort, the Goddess of Wealth; Saraswati, Brahma’s consort, is Goddess of Art and Knowledge; Durga ( “the invincible”) is a manifestation of Parvati, consort of Shiva, Goddess of love, fertility and devotion. Parvati’s older sister is the powerful goddess Ganges and mother of the much loved Ganesh. And on and on, there are 167 goddesses listed online most of them variations of the same principles.

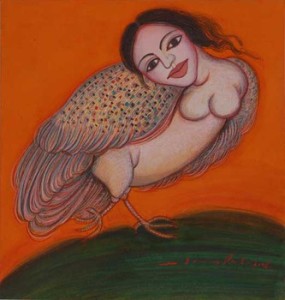

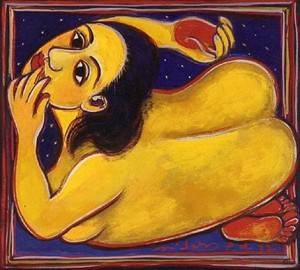

Gogi’s work has long been about the female spirit. She transforms ancient figures into contemporary forms. Rather than the obvious goddesses (although she has depicted Kali Goddess of Time, Change and Destruction), her work includes obscure mythical creatures based on early Sanskrit texts including the Kinnari ( (part bird, part female), nayika ( heroine) Kamdhenu, (wish fulfilling cow), burraq (dancing horse/human), hatha yogini ( firm, unyielding female yoga practioner). She has transformed these creatures and characters in her own way to express female power, resilience, and the contradictions of contemporary Indian society.

The only other specific historic person she has represented is Nati Binodini, a 19th century stage actress who defied conventional society, to pursue her career.

Born in Neoli, Uttar Pradesh, in the foothills of the Himalayas, where her father was a freedom fighter, Gogi also comes from a family who defied conventions. Her grandmother was the first woman to take a professional job in Lahore in the beginning of the twentieth century. She was also a pioneer in removing her outer heavy veil, leading to accusations that she was “naked”.

Gogi defiantly depicts all of her women as sensuous nudes who are also powerful and independent. Their big eyes examine us, challenging us to interfere with them. Sometimes they take on impossible yoga positions, or fly through the sky. Their sensuality is not only the result of their luxuriant shapes, but also the stunning, highly saturated colors the artist adopts. Still, as one art historian points out, Gogi was going against the flow of feminism as she pursued her commentary on women through naked bodies. It is partly the result of her grandmother’s act of defiance in removing the veil. Partly, the fact of the contradiction that women’s power according to societal norms, must be hidden from men behind coverings, and therefore it becomes a means of oppression.

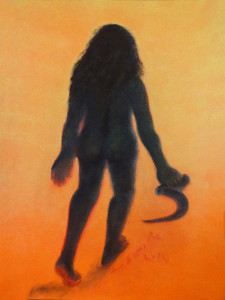

The new work for a young woman who wanted to fly through the sky, but was cut down from her dreams by a ruthless, ignorant act of violence includes a sickle, in several versions. A sickle is a traditional means of cutting, a reference here to the violence of destruction, as well as an attribute of power in the hands of Kali. In one painting, a silhouetted dark ghost of a powerful female strides away from us: grasps the sickle herself. This young woman sought to create change in society like Kali, the Destroyer of Time and Death. The painting suggests a space beyond our world. Unique in Gogi’s work we do not see her face, or her body, only a shadow.

Nirbhaya’s death as a sacrifice to social forces beyond her control, also looks back to the tradition of sati, the sacrifice of a woman on the funeral pyre of her husband, or even father, something Gogi has also represented.

But Gogi is honoring Nirbhaya, her hopes and dreams, even as she gives us the image of blood spattering over an empty rectangle, an empty life.

The ongoing violence against women in all parts of the world becomes part of the content of this group of paintings, as Gogi deeply understands both the history of powerful women and their vulnerable position in a changing world.

This entry was posted on January 27, 2015 and is filed under Contemporary Art, Contemporary Art In India, Feminism, Uncategorized, Women Artists.