“Permanent War: The Age of Global Conflict”

On September 11, 2001, privileged white Americans in New York City finally experienced what people of color everywhere already knew: civilian life in the US thinly masks a massive military endeavor that perpetrates death all over the world. On September 11, it backfired on us and erupted in our midst, physical and unavoidable. Likewise, the protests over police murders, #Black Lives Matter, highlighted our militarized police state, exposed and documented by smart phones.The hardware from wars streams directly into local police forces and into our lives.

Technology changes the experience of war, making it both more immediate and more detached.

“Permanent War: The Age of Global Conflict,” an art exhibition at the Boston Museum School Gallery curated by Pamela Allara, confronts us with artists who address the continuous presence of military actions past and present on the globe today. More than that, though, it focuses on the new dehumanization of war through technology.

We already know that our children and grandchildren need astute parenting to avoid being inundated by the military paradigms that penetrate every aspect of popular culture in games and toys and films and Hallowe’en costumes. Even more insidious, “war games” prepare them for the real thing. Of course, that is not new. How many of us played “cowboys and Indians” as children!

Pamela Allara states in her introduction to the exhibition: “If one is to judge from the artistic record provided by museum, human history has been synonymous with constant warfare. . . . the United States has based its economy on maintaining military dominance. However, the goals of our military interventions remain vague, as the many conflicts surfacing world-wide rarely have clear lines of demarcation between right and wrong, totalitarianism, or freedom. In addition, due to increasing mechanization, the very nature of warfare has changed, further challenging the concept of a ‘just war.’”

I am reading a history of non-violence at the moment and the author points out that there is no word for that concept in any language, except as the negative of violence. Gandhi tried to create a word, “satyagraha”(“truth forces”) but it did not gain traction. The author, Mark Kurlansky, also points out that the concept of “just war” came from St. Augustine, as an “apologia for murder on the battlefield. He declared that the validity of war was a question of inner motive. If a pious man believed in a just cause and truly loved his enemies, it was permissible to go to war and to kill the enemies he loved because he was doing it in a high-minded way” [i]!!!

The loss of a semblance of a consistent reference point for a “just war” (what Christianity used to be) underlies the ever shifting “high-minded” explanations for war today. In this exhibition, it includes Euro-US wars from the late nineteenth century to the present moment and around the world.

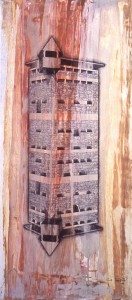

The chronological point of departure is Paul Stopforth’s Empire Building based on a stone fort from the Anglo-Boer War of 1899 – 1902. A great pun, the title refers to the European resource grabs in Africa. The technology of surveillance has not changed much since then in terms of its principles. Stopforth doubles this austere tower and makes no exit for the oppressors.

Paul Emmanuel, 3SAI: A Rite of Passage, 2008

Still from high definition digital video.

Courtesy of the artist.

Another South African, Paul Emmanuel addresses the present in that country in his video that witnesses the dehumanization of entering the military. After his head is shaved, the cheery blond becomes a frightening skin head, losing his individuality entirely. This relatively minor act of transformation signifies the much larger loss of humanity that people undergo as they enter the military.

Sig Bang Schmidt and Steve Dalachinsky, The Great War (WWI), 2002–04. Detail from the book of WWI photographs overpainted digitally (Schmidt) with accompanying poetry (Dalachinsky).Courtesy of the artist and the poet.

A collaborative work between poet Steve Dalachinksy and artist Sig Bang Schmidt, goes back to World War I for its source photography as they address in word and image the unchanged nightmares of war.That mechanized war perpetrated horrors on humans and cities beyond anything previously imagined. But from our perspective today, the “war to end all wars” seems short: 1914 – 1918, only four years. And it actually ended, albeit with a treaty that led to the next war.

Matthew Arnold, Artillery Emplacement, Bunker Z84, Wadi Zitoune Battlefield, Libya, 2012 from

Topography as Fate: North Africa Battlefields of World War II series.. Courtesy of the artist.

Recently Matthew Arnold revisited sites of World War II in Libya, and found derelict bunkers still in the landscape. Aside from the fact that we barely think about North Africa when we remember World War II, you can hardly see the bunkers in this photograph, all the more chilling as a comment on the meaninglessness of war.

Bonnie Donohue, Bunker in a Storm, Vieques, Puerto Rico, 2005. Archival Digital Print. Courtesy of the artist

Bonnie Donohue presents another site of derelict World War II bunkers in Vieques Puerto Rico, an American military base built on land expropriated from local people in 1941. Her entire project, installed in these bunkers, explores the “cultural, economic and health consequences of the U.S. Navy’s sixty-year occupation of Vieques, Puerto Rico as a military base and bombing range.” She even found a person who described the inhumane orders that forced his family to pick up and move their small shack themselves when the US arrived with its “just war,” right after the Pearl Harbor bombing. Only after massive protests, did the US finally leave Vieques in 2003.

These three works are in the section of the exhibition called “Landscape as Cemetary,” a potent description. That theme builds on American art and its tradition of land as a political site in the movement West, but with a new twist in the works of Donahue and Arnold with their lugubrious bunkers.

Another theme in the exhibition is “Living with War”which includes more recent wars and their ongoing damage.

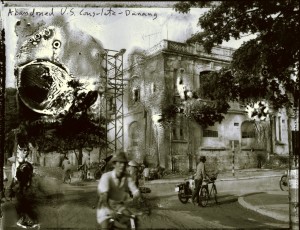

Bill Burke, Abandoned U.S. Consulate, Danang, 1994. Gelatin silver print from a Polaroid negative..Courtesy of the Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

In the 1980s Bill Burke visited men who continued to identify with their past as the part of the genocidal Khmer Rouge that terrorized Cambodia from 1972 – 1975. The former soldiers are still proud of “their weapons and terrorist strategies”. In this photograph damage in its development echoes exactly the long term damage in people’s lives and minds caused by that fruitless “domino theory” war in Southeast Asia.

Lamia Joreige, one of a group of artists who emerged in Beirut just after the long Lebanese Civil War (1975 – 1990), presents us with the repetitive damage of war under the theme “Combat as Performance”. Her three channel video based on archival photographs, reenacts a woman running on one screen, a man dying on the other, and the sea tinged with red in the center. The deadly repetition of terror and death for ordinary people caught in a war zone speaks to yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Its antecedent is Picasso’s Guernica, the first artistic representation of what is today a continuous reality, bombing from the air of unsuspecting innocents. But Joreige does not convey terror, only the repeated act of running and dying. Its unemotional re-creation echoes the detachment we have from the reality of bombing, which we so briefly experienced on 9/11.

Claire Beckett, Marine Lance Corporal Nicole Camala Veen playing the role of an Iraqi nurse in the

town of Wadi Al-Sahara, Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center, CA from the Simulating Iraq Series,

2008. Archival ink jet print. Courtesy of the artist and the Carroll and Sons Gallery.

Claire Beckett presents another type of performance in a simulated Iraqi village built by the US military as training camps in a California desert. Beckett features the play acting in which veterans or out of work actors play the parts of terrorists or devout muslim women. The contrivance of these scenes as the actors break for lunch clearly exposes the arrogance and stupidity of the exercises.

Harun Farocki, Serious Games II: Three Dead, 2010. Still from single-channel video. 8 min. Color,

sound. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York.

Haroun Farocki’s Serious Games II is based on virtual reality military training tapes, under the theme “Conflict as Media Entertainment.” These eerie robotic scenes clearly manifest that “just war” is making the world safe for commodity capitalism: we see Coca Cola signs hanging in the street. The absurdity of the actions, the us and them paradigm (in this case the other is barely represented), and the final victory scenes with tanks rolling into the town, clearly convey our hubris. But Farocki’s also emphasizes the difficulty of distinguishing simulation, fact, fiction and reality as a result of the invasion of technology into war in all its aspects.

Richard Mosse, Killcam, 2008. Still from video. Courtesy of the artist and the Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Richard Mosse’s juxtaposition of veterans playing video games in a hospital with drone videos (again pirated) of actually killing people by remote control. We watch the drone drop its massive, multimillion dollar payload bomb (reduced to a puff of smoke) on a remotely observed human being, assumed to be a terrorist by someone operating the machine in Utah. Then the screen switches to the veteran with a joystick killing in a simulated Middle Eastern village.

Coco Fusco, Operation Atropos, 2006. Still from single channel video. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York. © Coco Fusco/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Training for torture is Coco Fusco’s topic: she and a group of women enlisted in an actual torture training program using techniques developed by the US military to teach soldiers to resist being tortured. Here, we have training that is all too real, but at the same time it is a performance. The women who participated felt its horror, and many of them could not complete the program, even though they had volunteered to participate. The line of reality, simulation, fact and fiction is erased when people experience the brutal methods of interrogation that have become standard in today’s military.

At the same time, the lackluster response to the recent CIA report on our standard practice of torture, demonstrates how innured we are to it. Guantanamo Diary, by Mohamedou Ould Slahi, who has been detained for twelve years and is still not released, was recently published. It is a first hand account of torture hand written by Mohamedou in English that he has learned while in detention. Its heavily redacted text and years of legal actions to get it published speaks volumes about the CIA desire to prevent any first hand understanding of our technological wars. I am currently reading this riveting book. It details torture in its minutiae: day to day deprivations by heat, cold, sound, pain, hunger, insult, nudity and bodily function. Sign the ACLU petition to free him!

While some torture techniques are ancient, some, such as shocking the victim with electricity, also relates to another chilling theme in the exhibition, “Mechanized Bodies.”

We have seen mechanized bodies in the photographs of what a soldier wears today in terms of protection, armor, firepower, and vision equpiment. Ken Hruby, Adam Harvey, and Trevor Paglen take the idea in new directions ( The work by Paul Emmanuel discussed above is also in this group).

Ken Hruby, Short Arm Inspection, 1993. Detail from mixed media installation with plumbing parts Courtesy of the artist.

Hruby’s distrubing/humorous constructions called “Short Arm Inspection” suggest prosthetics, dismemberment and a subtle type of torture (the short arm is the penis, inspected by Drill Sargents in demeaning ways). Even as we laugh, we get the point of the extreme discomfort these inspections would have caused.

Harvey has created anti drone clothing that confuses heat detection technology (of course, in reality people have low cost substitutes like woven straw in Yemen and elsewhere).

Trevor Paglen, a geographer and an artist, obtained pirated video from a drone, its impersonality chilling, even as we know it is operated by a human being. He makes depersonalized drone warfare visible through its technology. But his concept reflects his training in geography, as he refers to the “infrastructure” needed for this type of warfare: “You end up developing a state within a state that has very different rules and different ways of operating than what we would think of as a democratic state.” He wants to help us “see secrecy.”

Most moving of all is Iraqi Jamal Penjweny’s video Another World (2013). I conclude with this work, as it is not simulated, it is footage of real people. Penjeweny filmed young men smuggling alcohol into Iran. It includes interviews with the men explaining the desperate financial conditions that led them to pursue this dangerous occupation. Shortly after the film was made, two of these men died. The reality of these deaths, what our immoral political leaders call “collateral damage” brings home the actual on the ground effect of war. For all our technology, the human body is subject in war to forces beyond its control and ultimately many people are dying because of that, including these young men.

“Permanent War” presents the repeated destruction and instant death of war enabled by contemporary technology. It explains our detachment from the realities that people today in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Lebanon, Syria, and so many other places (Yemen for example) live with every day, as the drones perpetually buzz, bomb, and kill. We are permeating our society with permanent military culture. Thanks to this exhibition, we are now more aware of some of its insidious methods.

Permanent War: The Age of Global Conflict” is at the gallery of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston January 29 – March 7 2015

[i] Mark Kurlansky, Non-Violence The history of a Dangerous Idea, Modern Library, 2008.

This entry was posted on February 25, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art in Beirut, Art in War, South Africa, Uncategorized.