Rodrigo Valenzuela, the 13th man and the end of Utopia

Rodrigo Valenzuela’s “Future Ruins” exhibition at the Frye Art Museum aptly characterizes where we are at this moment in Seattle, and in other cities that are tearing apart their historic urban fabric in order to cater to the rich with high end housing.

Rodrigo Valenzuela

Hedonic Reversal #13, 2015

Commissioned by the Frye Art Museum and funded by the Frye Foundation

Rodrigo Valenzuela

Hedonic Reversal #1, 2015

Commissioned by the Frye Art Museum and funded by the Frye Foundation

In his large installation Hedonic Reversal, Valenzuela presents us with constructed modernist ruins, with off kilter perspectives and installed as though in the midst of a construction site with shadowy ghosts of collapsing buildings painted on the wall. Here is a short video that sets the tone as he was creating the work http://www.rodrigovalenzuela.com/

He carefully explained his process, chalk, styrofoam strips, to suggest collapsing buildings, rephotographed over and over, but that has little to do with the overall significance of the works and the installation as a whole.

We see here the end of modernism, the collapse of utopia, the final chapter in a cycle that began with the Constructivists in the early 20th century. Artists like those of De Stijl, and the Russian Constructivists believed that art could build a new society, they idealized worker housing as a humane place, scaled to ordinary people, with usable spaces and shared community.

Yesler Terrace in Seattle is based on those ideas. Yesler Terrace is a community with shared public spaces and small scale. It was the first integrated public housing in the country. It is being torn down in order to make way for new market rate housing and high rises.Several enormous towers are being built on a part of the land sold way under market value to Vulcan, Paul Allan’s company. When Yesler Terrace was built it represented a utopian principle in action. Now its destruction stands for the end of those principles.

El Sisifo, 2015

3-channel digital video Commissioned by the Frye Art Museum and funded by the Frye Foundation

The video installation titled El Sisifo (Sysiphus) films workers as they pick up garbage after a game. . Sisyphus, the well known Greek story, tells of a king who was punished for deceitfulness by being forced to roll a heavy boulder up a hill only to have it roll down again. It suggests the repetitiveness and meaninglessness of the efforts of these workers punished with minimum wage or below because they have been accused by our society as poor people, as workers, as undocumented migrants. The rich accuse the poor and the poor follow a continuous round of mundane labor that serves the rich.

They are the 13th Man, as Rodriguo puts it, after the 12th man (the fans, the public) leaves. He films up close to a single worker with his uniform for a “cleaning service” (a service industry notorious for its exploitation of non union labor). The worker conscientiously finds every cup left behind and puts it in a garbage bag. But the artist also maintains a larger context, as he films from a distance: the tiny, anonymous workers move through the empty stands almost as though choreographed.On one of the videos a worker diagrams his route through the stadium, a dizzying set of movements.

The background sound track of “Pep talks” by sport coaches create an eerie contradiction to the silence of the stadium.

Rodrigo Valenzuela

Diamond Box, 2012

Digital video with audio (4 minutes)

Courtesy of the artist

Rodrigo

Rodrigo addresses worker issues in two other works. Diamond Box films the undocumented day laborers who stand by the road waiting for work. They are filmed in an anonymous studio setting, silent, but accompanied by a soundtrack of the stories of crossing the border, and their lives here. Their words are recorded in subtitles in English. It is a moving work, as the film protects the identity of the workers, underscoring their silent place in our economy, at the same time that we listen to their unbearably painful and hazardous life. By disconnecting the words and image, by having the workers simply sit silently, we sense the distance between what we can understand, what can be documented, and what has been experienced.

Rodrigo does not hide his elite intellectual approach to worker subjects. He came here as an undocumented migrant himself, but with an art degree and carpenter skills, and he describes reading Kant at lunch as a worker on construction sites. Later, he realized that the stories of his fellow workers were extraordinary. He mentioned to me that many of the day laborers have degrees as plumbers or technicians, but they have lost all possibility of professional employment by coming here, and often live in shelters in a state of deep depression.

A third video Maria TV addresses female domestic workers (nannies and maids) in a “Playback Theater” format which is described on Wikipedia as follows:

“Someone in the audience tells a moment or story from their life, chooses the actors to play the different roles, and then all those present watch the enactment, as the story “comes to life” with artistic shape and nuance.”

Rodrigo starts the piece with an excerpt from a TV “novella” about a woman who is told to leave her child forever, a strange echo of the real tragedies of separation that women choose when they leave their families behind in order to make money in the United States to send to their children. (They always believe they will be gone only a short time, but usually stay for many years. Enrique’s Journey by Sonia Nazario is the story of one of those children coming North to find their mother and what happens after they are reunited). The actresses enact both the melodrama of the novella and the real anger and frustrations of the domestic women.

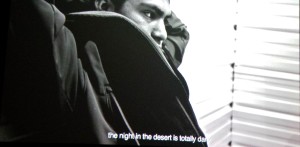

The artist declares that he is functioning at the border of documentary and fiction. His own experience of crossing the border is never told as a narrative although sometimes he seems to refer to it as in “Walk by Night” which films the desert day and night from a moving vehicle. It is not clear if the artist actually walked across this desert or is re imagining this space as one which has been crossed by so many migrants.

Rodrigo Valenzuela is attracting a lot of media attention and awards. He is well on his way to being an art star. His subject matter of the undocumented workers and their lives and (nonexistent) homes is distant from his present life in the United States (He gained citizenship by marrying).

One hopes that he doesn’t lose his soul in the glitz of art market success. The people and places he has been representing come out of the shadows of accusation, cliche, prejudice and exploitation. His success can hopefully enable him to cast an even stronger light on the human beings who stand so heavily accused in our society, but without whom our culture would collapse, to become ruins much like that vision of the future suggested in Hedonic Reversal. I still remember May Day 2006, the largest immigrant march to that date, when downtown Seattle came to a standstill as immigrants marched for their rights.

This entry was posted on February 7, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, Conceptual Art, Contemporary Art, Culture and Human rights, democracy, economic imperialism vs democracy, Performance Art, Photography, Uncategorized.