A valuable conversation of past and present: Three Special Exhibitions of Indigenous Art in Seattle

Last night I went to the Duwamish Longhouse just south of Seattle for a poetry reading that included Sasha La Pointe, the granddaughter of Vi Hilbert, the great savior of the Lushootseed language, whose portrait hangs in the lobby of the longhouse. Sasha has a lot of presence. What a proud history she has to draw on as a poet!

We are richly endowed in the Northwest with contemporary Indigenous artists working in all media. Fortunately we have two art museums here with a significant commitment to presenting their art. Currently, both the Seattle Art Museum and the Burke Museum are offering a valuable conversation between past and present Indigenous artists. As with all conversations, the complexity of these relationships emerge only gradually.

In spite of all of our efforts to brutally obliterate them in every way possible, indigenous people survived along with a few of their artifacts such as the magnificent work in the The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection on loan to the Seattle Art Museum from the American Federation of the Arts. Historic works like these along with their mythic stories handed down by word of mouth, as well as such surprising sources as Edward Curtis, enable contemporary Native artists to honor, revitalize and reinvent their past. The variety of media, content, and layers of history give the works both a compelling presence.

Sometimes those traditions have been re excavated only since the 1980s as in the case of the Yup’ik people of Alaska. Sometimes the artistic and cultural traditions have been known since the turn of the 20th century, when even at the height of cultural oppression, a few artists continued to work, such as Charles Edenshaw.

Figure (Pendant?), 3rd–13th centuryAncestral Columbia River people, Washington State or Oregon Antler 10 1/8 × 3 × 1/4 in.Diker no. 529

Courtesy American Federation of Arts

A few of the works on display at the Seattle Art Museum are amazingly early, such as this piece from the Columbia River Basin. Look for the other Columbia River partner piece from the 19th century that has a “she who watches” image on it, taken from the painting on rock near the Dalles from thousands of years ago, and a major theme for contemporary artist Lillian Pitt ( not included in the exhibition)

In other cases, much has been completely lost, but contemporary indigenous artists find ways to save what they can and re interpret it, as in the annual canoe journeys that have recently allowed tribal groups to gain a new sense of communal identity.

Preston Singletary

The rattle that sang to itself, 2010 Blown, Hot sculpted and Sandcarved Glass, Steel Stand 19 X 11 X 6 Inches, Photograph by Russell Johnson Courtesy of the Artist

Preston Singletary transforms a raven rattle from wood into glass, adding his own interpretations that are steeped in respect for tradition as well as contemporary life. (The piece illustrated is similar to the one in the exhibition.)

Reverence for the natural world has led many indigenous people to the activism necessary to save us. Happily, white environmental activists are now joining with them as never before

Mask, 1916-18

Yup’ik, Hooper Bay, Alaska Wood, pigment, vegetal fiber20 1/2 × 14 × 8 in.Diker no. 788 Courtesy American Federation of Arts

In the first gallery of the Seattle Art Museum’s “Indigenous Beauty: Masterworks of American Indian Art from the Diker Collection.” wooden Yup’ik masks from Alaska honor each creature that had been killed during the hunting season. They were given away each year, unlike so many other works in the exhibition that were made specifically for sale to tourists.

Organized as clusters of different media ( and do take note of the extarordinary range of different materials here), the exhibition includes works from the Western Arctic through to the Woodlands of the East Coast.

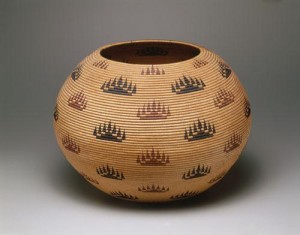

Some are quite familiar to us such as baskets from both California and the Plateau tribes, but we dramatically see the impact of white traders in the increased scale and new designs. Best known is Louisa Keyser who successfully pioneered large baskets with new motifs and new combinations of materials at the turn of the twentieth century.

Louisa Keyser (also known as Datsolalee, Washoe) Carson City, Nevada

Basket bowl, 1907

Willow shoots, redbud shoots, bracken fern root 12 1/2 × 16 5/8 in. Diker no. 326 Courtesy American Federation of Arts

Katsina dolls made by the Hopi were meant to be very personal to an individual, and only with persuasion did the Hopi create Katsinas for sale to tourists. This ogre Katsina is one of them. Since the original purpose of Katsinas is to provide an individual with guidance on how to lead a good live, this obviously was not made for that purpose.

Qötsa Nata’aska Katsina, 1910-1930 Hopi, Arizona

Cottonwood, cloth, hide, metal, pigment

18 1/2 × 6 × 10 in.

Diker no. 831 Courtesy American Federation of Arts

Beaded regalia which began after contact with white traders was taken in elaborate directions in both design and color by the Plains and other Indian groups such as here the Nez Perce from Idaho. This shirt would have been made before we started chasing those tribes North and stealing their land in the 1870s ( at the same time that Yellowstone National Park was created).

Man’s shirt, ca. 1850 Niimiipu (Nez Perce), Oregon or Idaho

Hide, porcupine quills, horsehair, wool, glass beads, pigment

32 11/16 × 60 2/3 in. Diker no. 666 Courtesy American Federation of Arts

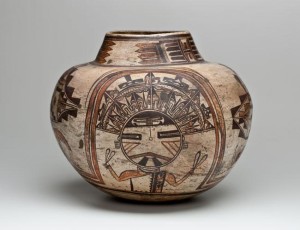

Historical continuity mixes seamlessly with innovation. An exceptionally large pot by Hopi artist Nampeyo from 1900, was built with coils rather than on a wheel. It features a mixture of archeological references and contemporary inventions. Nearby is an anonymous water jar from 1150 painted with a large hand in the midst of abstract patterns, an absolutely unique object.

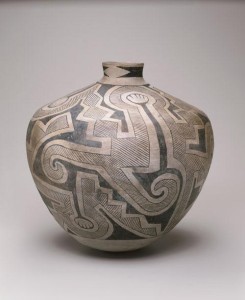

Water jar, ca. 1150 Ancestral Pueblo, New Mexico

Clay, slip15 1/8 × 15 7/8 in.Diker no. 313 Courtesy American Federation of Arts

Nampeyo (Hopi-Tewa) Hano Village, Hopi, Arizona

Water jar, ca. 1900 Clay, slip12 × 13 1/2 in.Diker no. 824Courtesy American Federation of Arts

The Seattle Art Museum partnered the visiting Diker collection with “Seattle Collects Northwest Coast Native Art” which is also filled with surprises. Look for the unique argillite piece collected by Bill Holm, the eminent and groundbreaking art historian of Northwest Coast Indian Art.

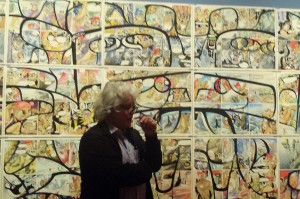

The large painting by Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas stands out in “Seattle Collects.” It combines Japanese Manga style and native Haida art motifs. Yahgulanaas dynamically explained his work in terms of form, history, and storytelling ( Red: a story of the punishment that results from a life lived for revenge). The artist is also one of the original Haida to resist logging on ancestral lands in the 1960s.

Unknown artist Tsimshiam, yellow cedar, operculum shell, paint 19th century Burke Collection 2252 Purchased from George Emmons and David Boxley Tsimshiam, Feast Dish yellow cedar, operculum shell, paint on loan from the artist

Equally provocative is the Burke Museum’s “Here and Now: Native Artists Inspired ”subtly installed by the museum’s designer Bridget Calzeretta. Based on the unusual concept of a living museum collection in which contemporary artists are encouraged to interact with specific objects, the exhibition marks the 10th Anniversary of a program at The Bill Holm Center that provides financial support for native artists to visit the collections. They don’t just look, they handle the art works, and they feel their energy transmitted to them. As Alison Bremmer put it “I was hit by the energy I got from the piece. I think the artist who made it would be really proud to know that it still carries that feeling all these years later.”

The Burke discovered that, after their visit, the artists’ work changed. In a dramatic demonstration of the impact of a program, they are pairing the work that most inspired a specific artist with a corresponding contemporary work. The result is a subtle and fascinating conversation between traditional art and contemporary arists. The contemporary works include close copies of older works in order to keep the traditions alive, creating a contemporary art work with the same materials and making a contemporary painting that directly connects to our culture.

David Boxley did a copy of a Feast Dish (see above). He declares “The original artist was really really good. It’s always been an inspirational piece for me . . . we all follow the same two dimensional design rules and what makes one artist different from the next is how he interprets his style into that strict set of rules.”

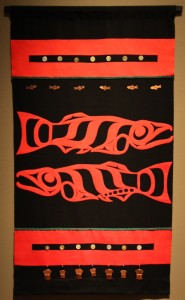

Lou-ann Ika’wega Neel created a contemporary art work of felt, suede, copper and abalone buttons, all traditional materials, inspired by a traditional wool cloth, one of the earliest acquisitions of the Burke Museum.

Sonny Assu Ligwilda’xw Kwakwaka’wakw #polatch shades of gray, acrylic on canvas, on loan from the artist and Equinox Gallery

Sonny Assu starts from historical regalia to create an abstraction that incorporates ipods: “ Having my great-great-grandfather Chief Billy Assu’s Chilkat regalia placed on my shoulders was part of the inspiration for this painting. This piece compares chiefly nobility – embedded with the knowledge and wisdom of his years as a chief – to how we formulate social status today through consumerism, branding, pop culture, and social media. “

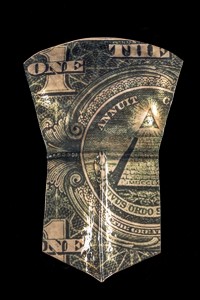

Alison Bremner based a work on the traditional copper Tinnah, an object exchanged at potlatches as a sign of generosity and status. She painted it with the “all seeing eye” of Satan from our dollar bill, marking it with the money economy that supplanted its historical purpose.

Nothing could be more apt to “Here and Now” than the original Eagle mask that inspired the Seahawks logo in the mid 1970s, borrowed just for this exhibition. The wooden mask would have been worn in a ritual dance. In the midst of the dance, it opened to reveal the ancestor of a family group. The logo connects one of the most popular rituals of our contemporary world to one of the fundamental rituals of the indigenous Northwest.

As a finale of “Here and Now” a woven work by Tommy Joseph incorporates the logo of Idle No More, the crucial environmental activist movement based in Canada.

From the Yu’pik mask, honoring the animals killed in a hunt, to Idle no More, honoring the earth by resisting its rape, this cluster of exhibitions, provides the continuity of indigenous cultures over thousands of years, its compulsions and rituals, its complex techniques, and its extraordinary creativity. They underscore that this creativity is embedded in a reverence for the interconnected spirits of the natural world that provides us with a crucial perspective. If we listen to this conversation and take part in it, we may find a way forward from our current crisis.

This entry was posted on March 20, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Contemporary Art, Contemporary Indigenous Art, Culture and Human rights, indians, Indigenous Art, Lillian Pitt.