Rameschwar Broota and Nalini Malani at the Kiran Nadar Museum in Delhi

On our first afternoon in India, we started with two world famous sites, the stunning Humayun Tomb (1565), the forerunner of the Taj Mahal and two newly restored nearby tombs, all part of an extensive necropolis in that part of Delhi. Then we went on to the Qutb Minar (1190), a minaret surrounded by a mosque made of recycled Hindu temple pieces.

But I was most excited to visit director and curator, Roobina Karode at the spacious Kiran Nadar Museum.

There we immediately immersed ourselves in the large scale paintings in the career retrospective of the work of Rameschwar Broota,”Visions of Interiority: Interrogating the Male Body 1963 – 2014.” In person, Rameschwar is soft spoken and understated. As he took us through the exhibition, he described his work in a quiet voice that belied the extraordinary experience of the works themselves.

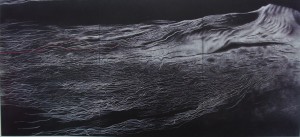

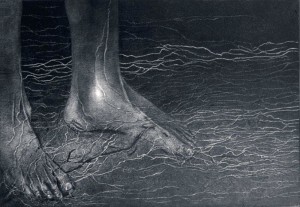

The first paintings we encountered seem to swell and flow on the wall, water, bodies, landscapes (I wish this was a bigger image, I am offering you a detail also here). But the undercurrent is both beautiful and threatening. Because of the large scale, and the subtle emergence of the body only in parts, in white lines on a dark ground, I felt unmoored, as though these works were creating a new world of which I was not a part, but which might envelop me.

Aside from the scale and imagery, the meticulous process that Broota has invented to create these works requires enormous physical stamina and discipline (some of them refer to principles of yoga, a practice he follows). He paints many transparent layers of close valued paint, silver,sepia, blue, black on the surface, then draws the imagery by scratching with an ordinary razor blade. The thin white lines emerge from the darkness and coalesce into the eerie flows.

The sense of continuity between the liquid coursing through veins in a body and the water flowing in the sea was unnerving. These works for me suggest the impending and ongoing ecological crisis of the planet. Its details emerge clearly, a foot, a body within the flow, but the overall scale is beyond us, beyond the canvas, stretching into a larger world. These works are referred to by the artist as “Traces of Man” or “Metamorphosis” in which the human figure is part of a huge environment.

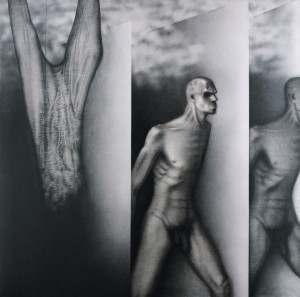

Broota focuses on a vulnerable male body. Much of the art in India is based on the female figure, heroic males or mythological creatures. These works are explicitly male (except for one based on his wife). In another series called “Runners” from the 1980s we see a lonely man separated from the world, seemingly existentially running or standing, or hanging upside down. “Prisoner of War” somberly presents an anonymous and generic prisoner.

Earlier work by the artist is more explicitly political. One series from the 1970s refers to politicians by using apes, in various amusing and cynical postures, as in “The Same Old Story.” Still large in scale, these satiric apes perfectly represent the political process in its self serving and and self referential narcissism.

The curator states:

Broota’s ‘Man’ in his primeval presence goes through the ambivalence of body and being, spirit and matter, fragility and resilience. With the trepidations of age, time, death and disintegration, one encounters the presence of male vulnerability in Broota that pushes the heroic male to often acquire an anti-heroic position.”

Broota, together with his wife Vasundhara Tewari Broota are both long time art teachers at Triveni Kala Sangam, the historical Delhi art school, founded by Sundari Shridharani in 1950, and designed by Architect Joseph Stein . Today it still has free classes. Rameschwar has been Head of the Art Department there since 1967.

Vasundhara is also an outstanding feminist artist. I was able to visit her studio on the following day. Here is an example of one of the paintings. She has recently shifted from small figures to very large ones. This painting of her daughter titled “Eye of the Tiger” 2012 suggests the emotional turmoil of adolescence. Its off center composition and layers of different moods are a stark contrast to her earlier work of women practicing centered yoga poses. But looking at her facebook, it appears that taking chances with many different types of images is characteristic of her work.

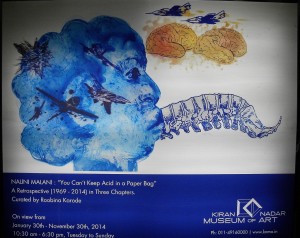

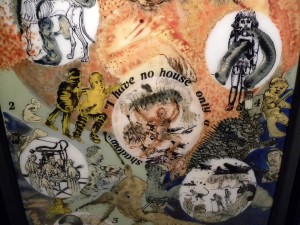

At Kiran Nadar, we also saw the last part of Nalini Malani’s retrospective “You can’t keep acid in a plastic bag.” This section’s title referred to her often referenced mythic women “Twice Upon a Time: Cassandra, Sita, Medea.” Malani seems to also follows science fiction: this image with its huge centipede like creaturecoming out the mouth reminds me of the symbiot people had inside them in the tv show “Stargate.”

Malani’s pioneering medium, reverse painting on mylar, here displayed in five adjacent and interconnecting panels (more usually on rotating cylinders with lights shining on them so that they project moving shadows) creates an unsettling presence, her work cannot be seen as material, the imagery seems to be changing before our ideas. Malani layers many literary and visual sources including pre Mughal frescoes from Rajasthan, Greek mythology, Western art, Indian history, Chinese art, evocative but unidentifiable botanical and biological creatures, (Nalani’s earliest drawings and watercolors were inspired by biology and botany ), her invented monsters, and much more.

For decades Malani has engaged deeply disturbing social issues through the representation of the human body such as in the “Mutants,” series about the horrifyingly deformed babies born after the Bikini Atoll nuclear tests.

In “Twice Upon a Time” monsters lurk, the earth seems to be enclosing many crawling creatures that suggest centipedes and worms or skeletal animals; oversize and overweight male figures, human or subhuman, occasionally dressed in a suit, suggest violence. Airplanes threaten pilgrims.

Andreas Huyssen, one of my favorite critical thinkers describes them thus

“It emphasizes the fragmentation and debasement of human form, but it does not suggest a currently fashionable anti-or post-liberating escape… there is no romanticization here of some otherness… nor is it… a take on the once fashionable Western exploitation of the abject. It is rather a way of registering and visually transforming the real violence and mutilations of the human , in specific historical and by now global contexts, without ever violating what once could call an ethics of the gaze on violence.” ( Nalini Malani In Search of Vanished Blood, Hatje Canatz documenta 13, 54.

In other words, Malani never loses her own direct emotional response to what she is representing and neither do we. We deeply feel the disintegration, disruption, deterioration of the planet, of the human condition as we look at her work.

Malani herself became a refugee from Pakistan, when she was only a year old at the time of the Partition of India and Pakistan, but it was not until the 1992 attack on the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya by Hindu mobs that she returned to that memory.

“In Search of Vanished Blood” a poem by Faiz Ahmed Faiz quoted by the artist conveys the nightmare of violence that leaves no trace. Here is a short excerpt:

“There is no sign of blood, not anywhere.

I’ve searched everywhere.

The executioner’s hands are clean. His nails transparent.”

This poem is one point of departure for her astonishing work of the same title at Documenta 13. Another reference point for this work is Cassandra by Christa Wolfe. The voice of Cassandra speaks in the sound track of the installation which creates an immersive environment of rotating mylar cylinders that create a frightening shadow play.

For many decades, Malani has addressed violence, political and personal, as well as cultural. Recently she has been horrified by the manipulation of Gandhi’s philosophy for political power and violence by the now Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi (who allowed the riots to rage unchecked in Ayodhya and even to encourage them.)

I first saw Nalini Malani’s work at the 2003 Istanbul Biennial installed in the huge underground Roman era cistern, a fitting place for her work, with its shadowy distances punctuated by heavy columns and eerie lights. I remember the moving mylar cylinders with mythical references that projected on a wall like a shadow play: As I wrote at the time:

“Nalini Malani’s work in the Yerbatan Cistern was magical. Her rotating circular acetate discs projected overlapping sequences of the shadows and reflections of fantastic beasts interspersed with guns and skulls on the wet floor, wall, ceiling. Projected against this was footage of the bombing of Hiroshima during World War II. Malani’s work took time to penetrate. The first impression was soft colors, light, and music. But as the bombing interrupted it, the fantasy world was psychically invaded by death and destruction.”

Malani’s embeds her work in deep philosophical roots. One of those roots is based on her formative years in Paris in the late 1960s when she came in contact with Simone de Beauvoir and other major thinkers such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Luis Althusser, and Roland Barthes.

Malani is acutely aware of her privilege created at the expense of the backbreaking labor of others, a situation so obvious in India where the medieval and the contemporary still exist side by side, the oxen pull the plows, as the wealthy drive the cars. As she has put it “I had a studio in a wholesale electric bazaar, and for me, the anomalies were that a lot of high tech instruments were being carried by porters on their heads. These people made homes without walls on the pavement, and during the rains they used the packing material that came from the boxes of high tech computers and sound systems to protect themselves from the rain.” ( 18 In Search of Vanished Blood)

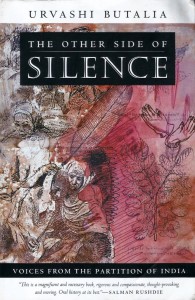

Nalani provided a cover illustration for Urvashi Butalia’s The Other Side of Silence, Voices from the Partition of India, (Duke 2000) one of the most intimate and revealing studies of the devastating impacts of the Partition on women, children and families. That silence is the foundation of consent and amnesia. The Partition is a blatant example of the power of arbitrary political decisions to cause death and trauma. But its after effects have only recently been exposed, unlike our ongoing wars everywhere in the world.

Malani and others are breaking that silence by actively creating space for us to begin to understand not only that atrocity, but also other nightmares that have resulted from political violence. That she uses mythic sources such as Medea and Cassandra, as well as Sita, all women who suffered at the hands of men, emphasized the global oppression of women. Mythic sources come out of cultural sources, emerge from society’s subconscious.

Broota and Malani both confront us with large ambiguous spaces and unsettling imagery that does not allow us to peacefully experience their work. They embed their art with different aspects of the vast Indian history and philosophy, but their art also joins the current global conversation on the state of the earth and whether we will continue into the future.

This entry was posted on March 25, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Contemporary Art In India, Feminism, Feminism, Uncategorized.