“Not Vanishing: Contemporary Expressions in Indigenous Art, 1977 – 2015”

Note: this post is dedicated to the Colvillle Indians who have just had a devastating loss of timber from this summer’s forest fires

The title “Not Vanishing: Contemporary Native American Art 1977-2015, curated by Gail Tremblay and Miles Miller at the Museum of Northwest Art in La Conner, Washington, obviously turns on its head the cliché of “vanishing races” applied to native groups from the turn of the 20th century. Edward Curtis embarked on his well-known photographic project of preserving them through photography at the time when assimilation and extermination were the ongoing policies of the US government.

This ambitious exhibition (lasting only until January 3) includes 78 works of art by 49 artists from 23 tribes in the Northwest, extending North into Canada and Eastward to Idaho and Montana. We are invited to look closely and think carefully at the many trajectories of the art work that point to layers of meaning and interpretation.

Featuring both well-known and emerging artists, the exhibition fills the Museum on both floors and embraces us with many voices. I can only touch on a few artists and ideas here.

At the top of the post, and here, is the work of Rick Bartow, an intense expressionist multimedia artist. This painting, called Going as Coyote, is carefully described by curator Tremblay in her essay:

“one immediately notices the way the artist divides the picture almost in half, the right side, dark, and the left filled with color and light. To the left of the center, the artist’s body leans forward toward the light and seems almost illuminated against the dark half of the drawing. . . .. He draws his own face with mouth open and teeth revealed. The top of his head transforms into a dark coyote face, also with teeth bared. The coyote’s ears are light and brightly colored.

“The artist portrays himself as a dancer, and carries the two dance sticks that define the front legs of an animal when one performs the role of that animal in a ceremony. In this drawing, he portrays the tension of existing in two different realities.

“In front of the artist is the dark shadow of an arm reaching into the light. It does not carry a dance stick but reaches like a third appendage into a space filled with hand and finger prints that as they rise transform into coyote tracks so the human marks of the dancer visibly merges with coyote, as dance and coyote face a space illuminated by all the colors of day …”

Tanis S’eiltin’s installation, Territorial Trappings, 2012 epitomizes the theme of the exhibition, the mixture of indigenous perspectives and contemporary art, native values and pressing environmental issues that affect us all. S’eiltin’s theme is Native ties to the fur trade that continued right into her childhood.

Fashions such as fur hats made from sea otters, or fur jackets from lynx hides directly benefited the livelihoods of indigenous peoples, but also impacted their traditional relationships to the natural world. The ambiguity of this economic trade-off is suggested in the gallery with a neon sign reading “Trade” backwards.

John Feodorov has always been fascinated by the role of white “spiritual” practices that co opt native spirituality, as well as recognizing contradictions within native culture itself. He describes his installation Domi-Nature:

“Domi-Nature is comprised of 12 white-washed Teddy Bears kneeling and praying silently before a projection of the three smoke-stacks from the Navajo Generating Station, a coal-fired power plant located on the Navajo reservation. The bears genuflect as if before a vision from heaven. This is an updated version to an earlier installation I created in 2001, just before the terrorist attacks on 9/11. Since then, this piece has taken on a more serious and tragic association for me, particularly with recent environmental tragedies such as the BP Oil Spill and the nuclear meltdown at Fukushima Japan.”

These two installations address environmental concerns from sharply contrasting perspectives, but both refer to the artist’s sense of urgency as well as the complexity of the relationships of native artists and the environment. While Indigenous artists and activists are taking a lead in protesting environmental destruction and climate change, others are working for those companies or encouraging and inviting power companies onto their land for desperately needed jobs.

Another artist who is acutely aware of these contradictions is Joe Feddersen. As a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes, in Eastern Washington and Southern Canada, Feddersen brings together stunning technique with subtle, but strong statements ( this image does not do justice to his exquisite work, the black verticals are a reflection of the photographer!). He worked for power companies earlier in his life, and you see on some of his work the geometric abstract form referring to those giant electrical transmitting towers. At the same time, those same towers carry energy from the Grand Coulee Dam, which destroyed many fishing grounds of the traditional Colville during its construction and subsequent flooding.

That tale is narrated from the perspective of his own family in Lawney Reyes’ book B Street. How the building of Grand Coulee Dam Changed Forever the Lives of One Indian Family and Devastated an entire tribe.” (University of Washington Press, 2008) A “Dreamcatcher” by Reyes is included in “Not Vanishing”, and an outstanding example appears in Seattle on Yesler and 32st as an homage to his sister and brother (the famous activist Bernie Whitebear).

The exhibition purposefully includes a range of media that range from weaving, beadwork, and carved cedar boards (here in John Hoover’s beautiful Loon Dance) to non native traditions of printmaking, acrylics, glass and bronze. These standing guardian figures by Joe David and Preston Singultary are made from blown and sand carved glass.

Often the works mix traditions and aesthetics, as in the entire room of extraordinary glass work by well known artists Joe Feddersen, Lillian Pitt, Preston Singletary, Caroline Orr, Susan Point, and others. That room epitomizes the cross cultural sophistication of these artists, as they work in a non traditional material but imbue it with both indigenous references and forms, as well as contemporary issues.

For example Lillian Pitt’s extraordinary Shadow Spirit in the Grass, draws on both indigenous meaning and contemporary ideas with cast New Zealand lead crystal and metal. Part of a series called “Shadow Spirits,” it is, as Tremblay writes, “cast by making a mold around a clay sculpture she created for the purpose.” Embedded in the clay are natural materials; here the imprint suggests a navel that “marks the connection between humans and the generations that precede them and make their lives possible.”

One of my favorite younger native artists included in “Not Vanishing” is Wendy Redstar. Her work humorously plays with the clichés about Indians, even while she makes a deeper point. At the time of the Seattle Art Fair this summer, Redstar installed numerous life size hunting decoy animals in Volunteer Park, a witty comment on one aspect of our contemporary interaction with nature. In this exhibition, her small car with the long title in two languages, iilaalée = car (goes by itself) + ii = by means of which + dánniiluua = we parade plays with contemporary perspectives on ceremony and indigenous identity.

Gail Tremblay and Miles Miller, the curators of the exhibition, fortunately included their own work as well.

Gail’s Exploding Star created by the painful technique of weaving with metal thread, refers to environmental issues as well as mythic traditions. In fact, in her introductory talk to the exhibition, Gail explained the work in terms of historic myths, but in her wall statement she spoke of “ materials we have ripped from the Earth who sustains our lives.” In other words, she connects the ancient and the contemporary in both the imagery and its significance.

Miles Miller, best known for his beadwork, here contributes two large prints “The Traditionalists” that speak of the Lewis and Clark expedition and its absurd misunderstanding of the native tribes that it met on its way West. He enumerates both their invented place names, as well as the anguish of the natives perspective.

“Not Vanishing” can also be analyzed from the perspective of mainstream art history styles: expressionism in drawings and paintings by Rick Bartow, James Lavadour, Jaune Quick to See Smith, and Sara Siestreem’s John Day Narrows here,

affiliations with Robert Rauschenberg in

the provocative imagery by Corky Clairmont, here, in his Split War Shield made from cast handmade paper that looks like tire tracks.

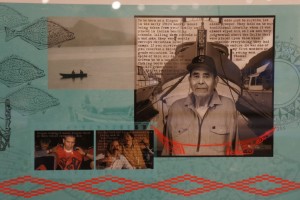

or the references to “pop art” in the amazing tribal masks from automobile parts by Larry Beck, to minimalism by Joe Fedderson in his reductive geometry, to realism in Larry McNeil’s poignant homage to his father

as well as the photographic realism of Matika Wilbur’s project redoing Edward Curtis (see my previous blog post about her work). And then, of course, there is the fact that Native artists practiced abstract art for centuries before it was “discovered” in Europe and the “American Abstract Expressionists.”

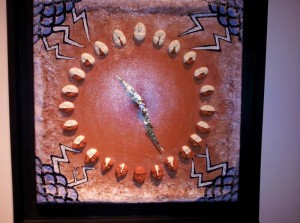

Erin Genia’s Blood Quantum Countdown affiliates with conceptual art as it poignantly points to why these artists so urgently sustain their cultural heritage in the midst of their immersion in the contemporary world. She explains: “Blood quantum originated during a historical period of the U.S. when Native Americans were viewed as a vanishing race. Today, it enjoys widespread use by tribal and federal governments as a legitimate method of determining whether a person can be considered an American Indian. This piece warns that continuing its use inevitably leads to a countdown to our extinction. . . Our survival as a people is based upon a whole spectrum of qualifying factors, from lineal descent to connection to our tribal communities, to protecting, preserving and revitalizing our tribal cultures. It’s time to reassess the viability of the blood quantum system.”

Indeed, the theme of “Not Vanishing” is exactly that, these artists in many ways are demonstrating the complexity of contemporary Indigenous art. The exhibition provides us with a window into what might be possible if the history of American art could be more truly inclusive. Like the exhibition “Our America” that focused on contemporary Latino/a art, this exhibition exposes a rich history of contemporary art that does not surface in the mainstream of art history except for token examples.

Living in the West, in the midst of dozens of contemporary tribes, all of them producing contemporary culture, I am acutely aware of this omission. When I go to DC a visit to the National Museum of the American Indian, right on the mall, is often at the top of my list. But when I speak of that museum to other art historians living there, they have never been there except perhaps to eat. This tells us a lot about marginalization.

Unfortunately, there is no printed catalog of this exhibition. There is a lot of written material which I understand will be posted on the website of the Museum of Northwest Art. Gail Tremblay’s powerful essay provides an historical trajectory for both traditional attitudes to indigenous art (heavily ethnographic), the stimulus of the 1930s Indian Arts and Crafts Act, as well as the Institute of American Indian Art, and one source for contemporary art history in the Northwest at the Sacred Circle Art Gallery in Discovery Park in the 1990s. At that venue, curators Steve Charles and Merlee Markstrum created a series of strong exhibitions by contemporary native artists. As a critic, these shows introduced me to several of the artists included in “Not Vanishing”.

The exhibition in La Conner, unfortunately rather distant from Seattle, ought to be at the Seattle Art Museum, or travelling to a major city. The fact that it is in a hard to reach museum, and has no published catalog, demonstrates that the struggle to integrate contemporary American art has a long way to go.

This entry was posted on November 24, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, indians, Indigenous activism, Indigenous Art, Photography, teddy bears, Uncategorized.

![unnamed[8] (1)](http://www.artandpoliticsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/unnamed8-1-300x300.jpg)