Art AIDS America at the Tacoma Art Museum on World AIDS Day

Note: Since posting this blog, there has been heavy criticism of the exhibition for its lack of African American artists and inclusion of their voices in the discussion, a fact that I mention in this article. (See images of Die In below).

I know that the museum has no Black staff people, ( as is true of most museums in the Northwest , the Seattle Art Museum for example).

I still feel that the show is significant as I write here. It is ironic, but not surprising, that an exhibition that is analyzing exclusion in art history ( that of the AIDS epidemic), is itself guilty of exclusion. I am glad to hear that it will be more inclusive of African American voices as it moves forward.

Deeply thoughtful and provocative, Art AIDS America, currently on view at the Tacoma Art Museum (until January 10), includes 127 works in multiple media. It includes the creative works of those who lived and died during the height of the epidemic in the 1980s as well as recent work by young artists. Curators Jonathan D. Katz and Rock Hushka intend to expose the radicality of the art as well as to remind us of the historic controversies of the 1980s that are still with us today.

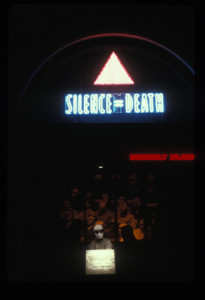

At the center of the exhibition is a recreation of the famous “Let the Record Show” installation at the New Museum in 1987.

I vividly remember that work as a turning point for the art world, at the height of the Reagan silence on the AIDS holocaust ravaging the US gay community, especially its creative workers: the large pink triangle came from the Nazi identification code for homosexuals, “Silence = Death” a poster from a group of the same name, an LED board documenting government silence as deaths mount and other facts. In the photographs at the bottom are Jesse Helms, William F. Buckley, Jr, and Jerry Falwell, among others, with quotes from their infamous comments on AIDS and homosexuals. Behind them is a photograph from the Nuremberg Trials, drawing a parallel between the the Nazis and the early 1980s.

AIDS was first labelled in 1981. In my personal experience, AIDS activism first vividly appeared in public at a Gay Pride march in San Francisco in 1983 when a contingent of very ill men marched to call attention to the still silent plague that was spreading so rapidly. San Francisco pioneered in treatment for AIDS, but it was many more years before it held widespread attention in the public, partly because of the absolute silence of President Reagan.

Wider awareness of AIDS was directly related to the creative activism by artists, writers, playwrights, poets, who began to write books (Randy Shilts 1987 And the Band Played On), write plays ( (Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, which educated a huge audience), and visual art in many media.

One of the earliest examples of confrontational creative activism was “Let the Record Show” at the New Museum. According to Avram Finkelstein, with whom I spoke at the press preview, there was a direct connection between AIDS activism and 1930s activism. He described himself as a “red diaper baby” meaning that his parents were communists, and he grew up with the idea of activism, street posters, and creative advocacy. At a weekly meeting of artists he suggested a poster, inspired by the Art Workers Coalition “And Babies” poster about the Vietnam War. As he put it, “Reagan’s silence was equivalent to a war crime.”

The exhibition in Tacoma is divided into several themes, “ Grassroots Activism,” “Poetic Postmodernism” “Memento Mori” “Spiritual Forces” “Portraiture”, and “The Legacy of the AIDS crisis.”

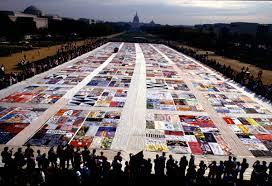

Grassroots Activism features panels and a digital display about “The Names Project,” the huge AIDS Memorial Quilt that began in 1987, with a square available to anyone who wished to memorialize a person who had died of AIDS related illnesses.

It travelled all over the country continually expanding until it filled the mall in Washington DC. with 2000 squares. Today it has 48,000 squares with a new square added every day; it is the largest piece of folk art in the world.

The NAMES Quilt of course belongs in the “Memento Mori” category of the museum as well as Grassroots Activism.

Tino Rodriguez’s Eternal Lovers, with its kissing calaveras, formatted in the spirit of a Mexican ofrenda tradition, introduces another well- known folk tradition of commemoration.

Memento Mori range from photographs of funerals to abstract imagery. One of the most touching is by Peter Hujar who himself died of AIDS two years after he took the photograph Ruined Bed, Newark in 1985. Because so many artists knew they were going to die, memento mori frequently are painful self portraits, such as those by Mark Chester and Mark Morrisoe documenting the progression of their own illness.

An exhibition about AIDS inevitably confronts the viewer with themes we prefer to keep hidden or buried in metaphor such as sexuality, illness, death, and homophobia. Of course, we are accustomed to these themes in the context of historical art, Catholic Renaissance art is filled with torture, sexuality and death, but when faced by the contemporary reality of these themes, we often look away in discomfort. But the compelling work here draws us into its painful subject. We are reminded of the deep commitment on the part of so many artists at that time. Included here are now well-known artists such as Jenny Holzer, Andres Serrano, Masami Teraoka, Duane Michels, Catherine Opie, Sue Coe, and Annie Leibowitz.

The challenge to engage us with subjects we would prefer to avoid, paired with, as Jonathan Katz so cogently analyzes in an outstanding catalog essay, the contemporary atmosphere of postmodern detachment and irony that prevailed in the art world in the 1980s, as well as the pervasive censureship of gay art, led artists who wished to represent AIDS to turn to what Katz calls “poetic postmodernism.” His prime example is Felix Gonzalez-Torres, whose work in this exhibition includes one of his trademark newsprint documents to take home, as well as a blue bead curtain that we gently part by Felix Gonzalez-Torres called Untitled (Water),

Other well- known artists pursuing abstract metaphors are Ross Bleckner and Scott Burton. Jim Hodges’ luscious curtain made of silk and cotton flowers When We Stay cascades down from the ceiling as open ended poetry, an homage of flowers to those who die, or a celebration.

“Poetic Postmodernism,” as defined by Katz subverted the abstraction that pervaded the art world. He even characterizes it as a “virus” that urgently entered the public face of art museums, as Barthes’ concept of the “death of the author” became horrifyingly literal. Katz contrasts poetic postmodernism to activist art which as he puts it “takes us somewhere”, “challenges our self- sufficiency.” Instead, poetic postmodernism “invites us to participate on our own terms.”

I found these distinctions convincing and helpful.

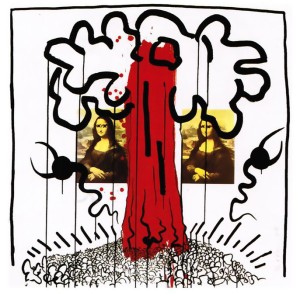

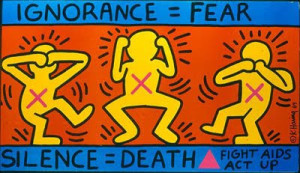

A crucial artist both in the 1980s and today Keith Haring came out of a graffiti background that doesn’t quite fit any of the categories, although the bronze with white gold leaf patina Altar Piece, completed posthumously in 1990, at the heart of “Art AIDS America” belongs to the spiritual category. His prints based on William Burroughs Apocalypse, 1988 ( above) exemplify Haring’s enormous, catalyzing energy, and spirit which many of us remember so vividly.

Women of course are a major aspect of the AIDS crisis, and an essay in the catalog focuses on them, although the exhibition has many more compelling works than the few discussed. One of the most striking is Ann Meredith’s Until that Last Breath! San Francisco California, photographs of women with AIDS, who asked to have their faces blurred for fear of retribution at their jobs or in their lives. Nan Goldin’s poignant series, The Plague, 1986 – 2001, a series of photographs of her friends who were living and dying during those painful years, as well as Kiki Smith’s Red Spill, 1996 still affect us viscerally. Smith’s work might be “Poetic postmodernism,” for its elegance and subtlety, but by creating an installation of large red glass puddles on the floor, we immediately recognize a literal reference to blood and to AIDS. Likewise Andres Serrano’s subtle red paintings at once read as blood, through some filter in our brains and eyes.

The exhibition brings the conversation up to the present, by including younger artists such as Kia Lebeija, whose startling self portraits evoke the lighting of a Nan Goldin.

Unfortunately absent from the exhibition are African American women, a major community in which AIDS-HIV continues to expand. Glenn Ligon’s, Untitled, (I am an Invisible Man), 1993 quoting from Ralph Ellison’s well known book, is not specifically about AIDS. ***Absence of black artists has been heavily protested with a die in and major confrontations

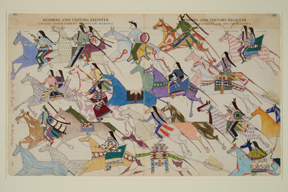

One Native American artist, Thomas Haukaas, contributed More Time Expected,2002. Consciously quoting one of the well- known ledger drawings created by Native people imprisoned in camps in the 19th century. Historically a riderless horse represented a fallen hero; here it refers to native people who have died of AIDS related illnesses.

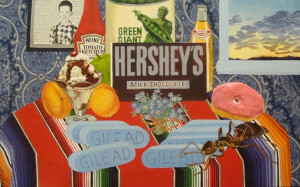

Latino AIDS activist Joey Terrell irreverently redefines and subverts the shallow materialism of pop art with queer references as well as Truvada, an HIV medication.

The exhibition intends to extend a conversation into the community, and to connect to activist groups that continue today to confront homophobia, prejudice against people living with AIDS and HIV diagnoses.“Negotiating HIV is a conversation essential for everyone” Curator Rock Hushka stated.

This exhibition consciously contests the omission of AIDS art from the main trajectory of American art history. As this 1980s generation of creative thinkers began to confront ways in which to infiltrate and alter the basically apolitical, detachment of American contemporary art, their strategies and tactics permanently altered the very character of contemporary art production. Katz characterizes “camouflage, ” and “infiltration” and “spying” as strategies these artists adopted to position their work in museums whose tolerance for the topics of illness, homosexuality, and contemporary death, was zero. As a result, the art world has been permanently altered.

Rock Hushka’s catalog essay “Undetectable Presence of HIV in Contemporary American Art” speaks to abolishing the “silence” about HIV. Today is World AIDS Day, and around the world, people are commemorating it. Here is an image from Nepal.HIV is a global problem now and continuing to expand.

In the US, it has traditionally also been a “Day Without Art” since 1989.

As reiterated by both curators, the artists who insisted on breaking the silence of both the political world and the art world, permanently expanded the strategies and content available to artists. They opened doors for activist artists committed to exposing injustice. The purpose of Art AIDS America is to demonstrate that a new genre of political art emerging from art about AIDS belongs in the mainstream of American art history, rather than as a brief footnote. They convincingly persuade us of that in this major exhibition.

captions and credits:

ACT UP NY/Gran Fury (active New York, New York, 1987–1995), Let the Record Show…, 1987/recreated 2015. Mixed media installation, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Gran Fury and the New Museum, New York. Photo courtesy of the artists.

Tino Rodriguez (born 1965), Eternal Lovers, 2010. Oil on wood, 18 × 24 inches. Private collection. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Keith Haring (born 1958, died 1990)

From the Series Apocalypse, 1988

silkscreen, edition of 90 38 x 38 in

Courtesy of the Keith Haring Foundation

Thomas Haukaas (born 1950),

Tribal Affiliation: Sicangu Lakota, More Time Expected, 2002. Handmade ink and pencil on antique ledger paper, 16½ × 27½ inches. Tacoma Art Museum, Gift of Greg Kucera and Larry Yocom in honor of Rock Hushka, 2008.10. Photo by Richard Nicol, © TAM.

Kia Labeija (born 1990), 24, 2014. Inkjet print, 13 × 19 inches. Courtesy of the artist. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Joey Terrill (born 1955), Still Life with Forget-Me-Nots and One Week’s Dose of Truvada, 2012. Mixed media on canvas, 36 × 48 inches. Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, Foundation purchase. Photo courtesy of Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art.

This entry was posted on December 1, 2015 and is filed under American Art, Art and Activism, art criticism, Contemporary Art, democracy, First Nations Art, Uncategorized.