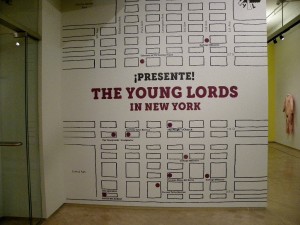

“¡Presente!: The Young Lords in New York”

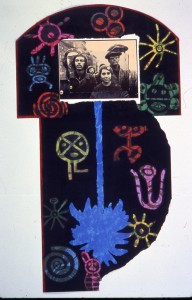

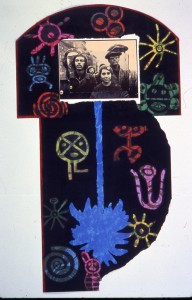

Juan Sánchez

“Once we were warriors ” 1999

The Collection of Julio and Isabel Nazario

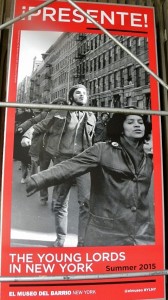

“¡Presente!: The Young Lords in New York,” at El Museo del Barrio presents an eye opening history of the Young Lords, crucial as both political and art history. The exhibition is particularly relevant today as Puerto Rico, still a “self governing commonwealth” of the US, faces financial bankruptcy and is still at the will of the US Congress to resolve the crisis. Because the US successfully subverted the independence movements and imprisoned its leaders throughout the 20th century, Puerto Rico cannot act on its own.

This exhibition reminds us of the strong demands for independence in the early 1970s, and its earlier stages all the way back to 1868 and El Grito de Lares when the first nationalist party was founded. The exhibition had two other venues in New York City, both locations of Young Lord activism, the Bronx Museum of Art and Loisiada, Inc on the Lower East Side where the group was founded in Tompkins Square.

At El Museo del Barrio, the exhibition has special resonance, as that museum began during these same years, its history as a cultural center serving the community embedded in the same issues that concerned the Young Lords.

At El Museo del Barrio, the exhibition has special resonance, as that museum began during these same years, its history as a cultural center serving the community embedded in the same issues that concerned the Young Lords.

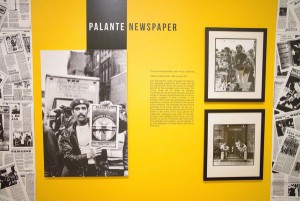

Film, photography and archival material from the El Museo collection documented the activities of the Young Lords in East Harlem particularly in the period from 1969-71.

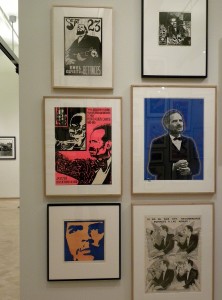

Stunning posters, paintings and sculpture filled one gallery, while other galleries included many archival documents in a dramatic installation.

Juan Sánchez’s striking mixed media artwork “Once we were warriors” honors the Young Lords’activism. Sanchez as part of El Taller Boriuca

( “Puerto Rican workshop” established across from the Young Lords headquarters in East Harlem) began to explore his African and Indigenous roots as well as the brilliant graphic arts traditions of the island. Symbols in the print refer to those traditions.

The founding members of the Taller, Armando Soto, Marcos Dimas, Carlos Osorio, Adrián García, Martin Rubío, Neco Otero organized sit ins to advocate for community-based programs within museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and joined boycotts with the Art Workers Coalition who sought to close all the museums in New York City after the Kent State Massacre. Taller held a sit in in Thomas Hoving’s office.

They founded the workshop, as Marcos Dimas has written, because they felt that there was a “cultural void” within the Puerto Rican community. As they organized exhibitions in the streets and donating art to the community, the print workshop cross fertilized with Puerto Rican based artists and created vivid prints of both historical figures and contemporary struggles and issues.

For example, they honored Ramón Emeterio Betances y Alacán (1827–1898) ( upper left), a social hygienist and surgeon who organized the 1868 El Grito de Lares that inspired the nationalist movement in Puerto Rico. He is considered the father of the independence movement.

Another crucial inspirational leader honored here in a print was Pedro Alibizu Campos (1890 – 1965) ( above middle left).

And there is Lolita Lebron (1919 – 2010) here in a 1971 print by Manuel García asking for freedom for Puerto Rican political prisoners. Lolita, with four other nationalists fired guns at Congressmen in 1954 to advocate for Puerto Rican independence. She was put in jail for 25 years, then reemerged still activist and Puerto Rico’s most famous freedom fighter.

![Carlos Irizarry / Moratorium / 1969 / Screenprint / 21-3/8 x 27-3/4 in. / Collection El Museo del Barrio, New York [W91.116]](http://www.artandpoliticsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/irizarry-moratorium-1024x754-300x221.jpg)

Carlos Irizarry / Moratorium / 1969 / Screenprint / 21-3/8 x 27-3/4 in. / Collection El Museo del Barrio, New York [W91.116]

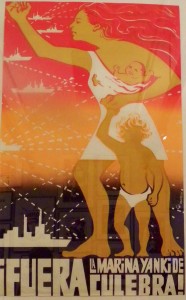

Antonio Martell’s lushly colored print calls on the USA military to leave the Island of Culebra, off the coast of Puerto Rico (as a result of protests, the military left in 1975, but remained on Vieques).

A second culture center with an emphasis on experimentation was founded by Eddy Figueroa on the Lower East Side with the name “New Rican Village Cultural Arts Center in the East Village.”

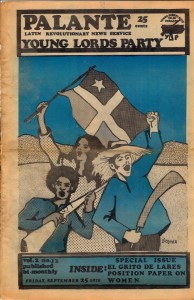

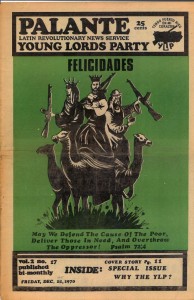

The same pairing of an urgent need to tell Puerto Rican history and address immediate issues characterized the Young Lords movement in general. Indeed, their writings today provide a striking example of the thorough historical research and economic and political analysis that these young activists provided in their newspaper Palante. A thirteen point platform developed in 1970, had one point revised at the behest of the powerful women ( below we see Denise Oliver Velez, then and now) in The Young Lords to state “down with machismo.”

With these historical perspectives in mind, the activism of the group deeply reflects the Young Lords desire to rise above the racist abuses of their childhood, abuses that permeated every aspect of their daily lives. The accounts of their childhood experiences, collected in their 1971 book Palante Voices and Photographs of the Young Lords, 1969-1971, just reissued, lay bare the character of their ghetto life.

Many of these young activists saw only the opportunity for young death in drug dealing and gangs. The thrill of discovering another way forward through the activism of the Young Lords comes across clearly in the essays they wrote at the time. Strikingly, several of the early Young Lords had escaped that life and gone to college, during the early days of affirmative action, but they returned to their hood to organize and give back to their own community.

Outside the exhibition, a large map showed some of the most famous interventions by the Young Lords, focusing on basic community rights, housing, health care, education, nutrition. These four painted wooden rifles by Miguel Luciano commissioned in 2015 for the exhibition state those goals.

More specifically, the Young Lords as a protest against poor or non existent collection, they and community members piled garbage in the street and set it on fire to block the road, causing a major disruption in traffic; they co opted TB vans to deliver innoculations to the Barrio; they protested working conditions in hospitals, they occupied a church in order to open a day care center and provide breakfast.

Inspired by the example of the Black Panthers, and initially affiliated with a group in Chicago of the same name, The Young Lords evolved in distinct phases, the early community based activism, the organizing phase 1970 – 72 and the ideological, international phase, 1972 – 76.

Máximo R. Colón / Partido Young Lords / ca.1970 / Gelatin silver print / Courtesy of Máximo R. Colón

Extraordinary photographers Hiram Maristany, Frank Espada, Geno Rodriguez, and Máximo Colón, among others, documented their actions providing us with a vivid and inspiring record of commitment.

As with the history of so many activist groups, there were efforts to reach out to all strata of society, deep motivation to make life better for their community, along with internal power struggles, efforts to develop ideologies, and ultimately, a decline based on alienation.

Ironically, the final decline for the Young Lords was the result, according to the documents presented here, of leaving behind their immediate community and extending their activism to Puerto Rico itself by closely affiliating with the on-going nationalist struggle for an independent country. At the same time, the ideology hardened and the leadership became more dictatorial. That proved a lethal combination.

![Carlos Osorio / Simbolos que nos joden / 1973 / Oil over acrylic and sand on canvas / 24 x 22 in. / Collection El Museo del Barrio, New York / Gift of Jimmy Jimenez / [P92.80]](http://www.artandpoliticsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/osorio-c_symbols-that-enslave-us-941x10241-276x300.jpg)

Carlos Osorio / Simbolos que nos joden / 1973 / Oil over acrylic and sand on canvas / 24 x 22 in. / Collection El Museo del Barrio, New York / Gift of Jimmy Jimenez / [P92.80]

But the amazing accomplishments of the Young Lords in just a few short years, as well as the rich body of art that the Taller Boriuca produced, lives on in these new exhibitions and publications.

They are a model for what a committed and diverse group of young people (the Young Lords included African Americans, feminists and a famous transgender performer, Sylvia Rivera) can accomplish with direct action, love of their community, and willingness to defy oppression. We can draw a direct line from them to the Black Lives Matter movement.

This entry was posted on December 8, 2015 and is filed under American Art, Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Black Panthers, Feminism, Feminism, Uncategorized.