The Museum of Modern Art and the Art of Disruption

I never dreamed that during my one month in NYC I would find myself repeatedly returning to the Museum of Modern Art for one show after another that provoked my ongoing analysis of art and politics as well as my long time interest in the way that the history of modern art is constructed particularly at MOMA. But that is the case.

Glenn Lowry Director of the Museum, spoke in a recent interview in the Brooklyn Rail of the role of the Modern Art Museum as disruptor, as having a history of disruption. Although that seems to be the trendy word in the last few years among the in crowd of “social process art”., Lowry actually cites Alfred Barr, the first director in his foresighted collection of film, architecture and design as well as his reaching out to art of Latin America, Asia, and Native Americans (certainly the latter is still a weak suit at the museum) as examples of disrupting the status quo. (Of course at the time the Museum of Modern Art was barely surviving on the largesse of Abby Rockefeller, so collecting in those areas was probably also a financial move, they were cheap and also easier during World War II).

Given that commitment to disruption, it is therefore not surprising that I have found in several exhibitions, as well as in odd corners of the museum, various disrupting displays. For now, I will put aside Walid Raad, the most obvious and complex example. I am planning to return to him in a separate post.

The first surprise was outside the café/restaurant on the second floor where we could see a Richard Serra video from 1973, Surprise Attack, (you can view the video at the link) in which he tosses a lead brick from one hand to the other. We might say, OK, we know his art from so many years, without paying attention. But someone discovered this early work and installed it. The reason: it is absolutely resonant with our political environment today.

Serra is reading from a text as he tosses his lead brick back and forth back and forth. The text is Thomas C Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict ( 1960). Schelling, a game theorist, writes about the “amplified threat of violence” that comes from failure to communicate with others and to understand them; for example, each of two armed people suspects the other will act first. While Serra doesn’t take it to the next step, he just keeps tossing his lead brick, it is obvious that we are there today, both in our homes (Serra/Schelling’s example is an armed homeowner and armed robber) and in international politics on every level. Of course, the US is always willing to play the bully these days, and skip the veneer of diplomacy.

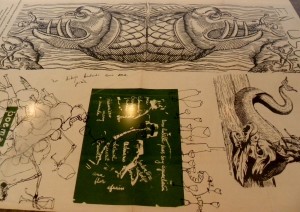

Down in the depths of the education wing another surprise, archival materials from the well known radical group from Venezuela ” El Techo de la Ballena (Roof of the Whale).” Drawn from a donation to the Museum of Modern Art Library, the small exhibition of archival catalogs and photographs, with a video enhancement, lays out the radical left program of the more than sixty artists, poets and writers from Venezuela from 1961-69. It emerged during a period of democracy after a decade of dictatorship rule. They were energetically rejecting the dominant tradition of geometric abstraction in Latin America, (manifested in the universal constructivism aesthetic epitomized by Uruguayan Joaquin Torres Garcia, whose major retrospective appears on another floor of the museum.)

Here we have the intentionally messy, rude artists, aligned with Communists, protesting the status quo with ‘l’art brut” and surrealist approaches. The roof of the whale as a title refers to enormous power rising from the depths where it has been held submerged. They saw it as almost a volcanic power. Unfortunately, the show is a far cry from the volcanic energy the group proposed, set out in boring glass cases. A screen above highlights some quotes and images, but the real energy of the movement would be well served by a performance event with poetry readings in Spanish and English.

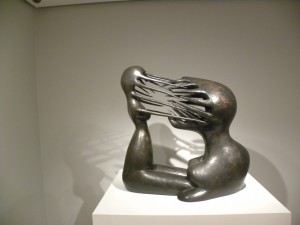

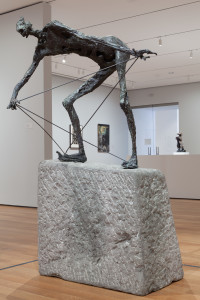

More prominently exploring a political theme, as well as the figure, “Soldier, Spectre, Shaman: the Figure and the Second World War” opened with a strikingly original sculpture by Maria Martins, The Impossible III 1946, a bronze in which two figures spar; aggressive organic appendages replace their facial features. The larger body seems to suck at the other, while the slimmer figure holds back, not surrendering, an image of conflict and unresolved aggression.

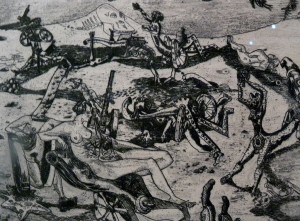

Nearby, in a small etching by David Smith, Women in War, 1941, a woman “reclines”in the foreground of a battle scene in which women are pursued, killed, raped. The image was printed in an edition of 16 and it follows his better known Medals for Dishonor series of 1937-40, but it is actually more unblinking in depicting atrocities of war.

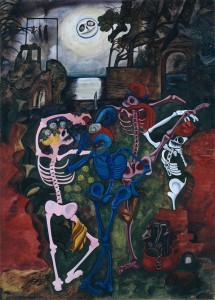

Still at the entrance, Edward Burra’s painting Dance of the Hanged Man 1937 ( the work here is in the Tate of Dancing Skeletons 1934 to give tstretching the chronology of the exhibition backward into the 1930s. Burra’s awareness of pain through his own life long disability, led to original and complex paintings about anguished suffering. The Dance of the Hanged Man shifts scales dramatically between the giant oppressors and the victims.

The main body of the exhibition includes a galaxy of sculptures by artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Jean Fautrier, Alberto Giacometti, and Joan Miro ( see top of post for Miro).

But Germain Richier’s savage and aggressive The Devil with Claws 1953 dominates the room.

Two intense groups of work are by Japanese artists. Shomei Tomatsu photographed people in the aftermath of the dropping of the bomb on Nagasaki, a place he revisited repeatedly during the American occupation : “What I saw in Nagasaki were not only the scars of war, but a never-ending postwar. I, who had thought of ruins only as the transmutation of the cityscape, learned that ruins lie within people as well.

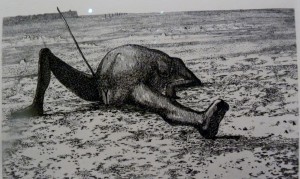

Small etchings by Chimei Hamda, include Elegy for a new Conscript: Landscape 1953 (above) hard to look at in its immediacy. They reverberate with the artist’s memories of the horror of a soldier’s death in the desolate landscape of Northern China during the Sino Japanese war 1937-45 in which the photographer served as a conscript when he was a young man.

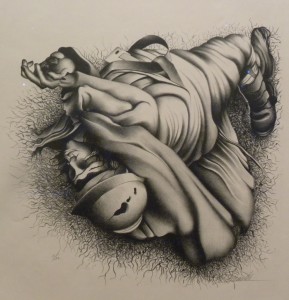

An intensely precise drawing by Mexican Francisco Dosamantes honors a dead soldier in the Spanish Civil War.

The show falls apart for me in the Shaman section, when it settles for East Coast based artists who are pulling from Native American spirituality. There are no native artists included, only one African American (Romare Beardon). Another artist who definitely did not belong was Henry Darger, one of my least favorite artists who seems to be so exciting to so many people. He creates private fantasies that have little to do with the heavy realities that the best work in this exhibition address. He is, not surprisingly, in the shaman section as well.

The strange inconsistencies of the selection are echoed in the subtitle of the exhibition, with its reference to the Second World War, in spite of the fact that several of the works predate it or refer to other wars. Why not the Figure and War, making the same point more emphatically, and skip the later shamans. The first two rooms of the exhibition are stunningly installed, selected and create a strong statement. I don’t understand why the exhibition didn’t stay focused on artists’ responses to the nightmare of the human body violated by war in the mid twentieth century.

Still, the number of expressive works that convey the horrors of war confirms that the museum no longer settles only for aesthetics. It wants to be responsive to our contemporary nightmares and demonstrate that artists have a role to play in revealing it, very much in the tradition of Alfred Barr. Rather than disrupting a tradition, the museum is actually reclaiming one. Barr favored the “Neue Sachlichkeit” artists and the grotesque until he became the director of the museum at the tender age of 27. In the 1920s Barr had already moved beyond Picasso’s cubism (and so had Picasso of course).

In 1936 under the duress of Hitler’s attacks on modern art, Barr invented the history of modern art with his “Cubism and Abstract Art Exhibition” and his famous chart, omitting all of his early digressions into grotesquerie.

The current impulse to disrupt returns to Barr’s young inclinations, before he was shaped by patrons, his own institution and politics. These shows, drawn entirely from the permanent collection, document a new willingness to disrupt genealogy as well as to embrace contradictory impulses.

The Pollock exhibition, all from the MOMA collection (and not all of what they have by any means), included many benchmark works, but again we see new perspectives. The Curator chose to give more in depth treatment to the forties ( this one untitled 1945), the transitions as they are called, allowing us to see the bizarre hesitations, rather than simply settling for a grand progression to the final drip paintings. Also the ongoing of Thomas Hart Benton’s principles of organization are obvious if you know what to look for. Pollock always said he rejected Benton, but it isn’t true.

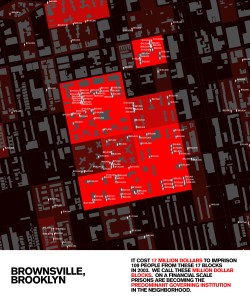

Likewise In “Scenes from a New Heritage” the reinstallation of the contemporary collection, some surprising work pops up, particularly “Mapping Justice. ” by a team of artists based at the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture that documents the 17 million dollar cost of imprisoning 19 people from 17 blocks in Brooklyn, so called “Million Dollar Blocks.”

Nalini Malani’s Gamepieces layers mythology with contemporary violence, in her trademark circling acetate spheres, painted with figures that move like an early movie across the wall. Camille Hernot’s film Grosse Fatigue tells the story of the creation of the world juxtaposing contemporary technology and historical archives, playfully, provocatively, tragically. Huseyin Alptekin’s photographs of cheap Istanbul hotel signs made sense to me because I have known his work for many years, but I doubt anyone else got his larger point of class and power issues.

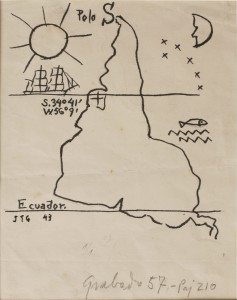

I can’t leave out the Joaquin Torres-Garcia retrospective, since it is the first showing of this great modernist’s work since I assisted with a retrospective in 1970 in my first job as curatorial assistant to the late great curator/director Daniel Robbins. A lot of Torres Garcia’s work burned in a fire in Brazil in 1976, not long after our exhibition, but thankfully the Museum of Modern Art curator, Luis Pérez-Oramas has been able to put together another stunning show of this pioneering artist, teacher and philosopher. This Uruguayan artist influenced artists all over Latin America. The fact that he is not mainstreamed in art history is ongoing eurocentrism. This exhibition is a glorious retrospective including his earliest street art and peculiar murals in Barcelona, his books, his toys, his constructive sculpture. His brilliant inverted map of South America proclaimed Latin America as a center of culture.

Finally, that crazy Katerina Fritsch sculpture in the garden parodies Rodin’s Burghers of Calais, but not just to be funny. Take a close look and you see some scary ideas. MOMA this January was really a disruptive place and I loved it.

Photo Credits:

Edward Burra, Dancing Skeletons, 1934, gouache and ink on paper, 78.7 x 55.9 cm, Tate Collection.

Shomei Tomatsu (Japanese, 1930-2012). Hibakusha Tomitarō Shimotani, Nagasaki. 1961. Gelatin silver print, 13 × 18 3/4″ (33 × 47.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist © 2015 Shomei Tomatsu

Laura Kurgan, Eric Cadora, David Reinfurt, Sarah Williams, and Spatial Information Design Lab, GSAPP, Columbia University. Architecture and Justice from the project Million Dollar Blocks (detail). 2006. Digital prints and Powerpoint file with images generated from Esri ArcGIS (Geographic Information System) software. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the designers, 2008. © Laura Kurgan, Spatial Information Design Lab, GSAPP, Columbia University

Nalini Malani (Indian, born 1946). Gamepieces. 2003/2009. Four-channel video/shadow play (color, sound: 12 min) and synthetic polymer paint on six Lexan cylinders. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Richard J. Massey Foundation for Arts and Sciences, 2007. Photo by Thomas Griesel. © The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Joaquín Torres-García (Uruguayan. 1874–1949). América invertida (Inverted America). 1943. Ink on paper. 8 11/16 × 6 5/16″ (22 × 16 cm). Museo Torres García, Montevideo. © Sucesión Joaquín Torres-García, Montevideo 2015.

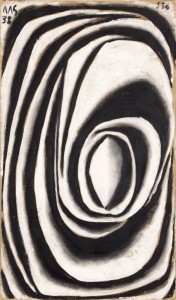

Joaquín Torres-García (Uruguayan. 1874–1949). Forma abstracta en espiral modelada en blanco y negro (Spiral abstract form modeled in white and black). 1938. Tempera on cardboard, 31 7⁄8 x 18 1⁄2” (81 x 47 cm). Private collection. © Sucesión Joaquín Torres-García, Montevideo 2015. Photo ©2015 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo by Christian Roy

All other photos by Susan Platt or Henry Matthews

This entry was posted on February 20, 2016 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Uncategorized.