Walid Raad Scratching on Things I Could Disavow

Walid Raad “Translator’s Introduction:Pension Arts in Dubai” 2012 paper cutouts, two channel video

Walid Raad experienced much of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-91) at long distance after he left Lebanon as a teenager in 1983 to attend high school and college in the United States. That distance forms the foundation of his work, his understanding that the construction of history is serendipitous, fragmentary, and heavily mediated. Research into archives is also questionable, because what survives in an archive is also accidental. Adding to this the distortions of trauma that are embedded in war and its experience, we have nothing but our imaginations and scraps of information to count on. Hence, Raad’s contention that distinguishing fact and fiction is beside the point. He claims that everything he says is factual, but there are different types of facts: emotional, aesthetic, historical, psychological.

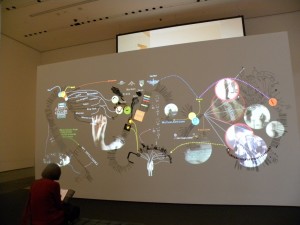

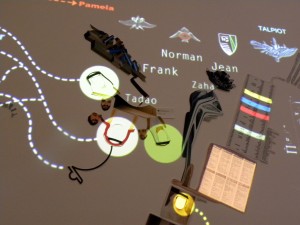

The installation and performance titled “Scratching on Things I Could Disavow” consists of several parts at the Museum of Modern Art, a computer projection or tableau as the artist calls it, which forms the backdrop of his performance, (see top of post)

a wall of large apparently blank colored squares of varying sizes,

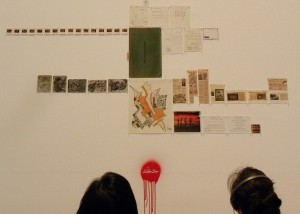

a wall claiming to examine art history in Lebanon with archival documents

a small scale museum with miniature images of Raad’s work,

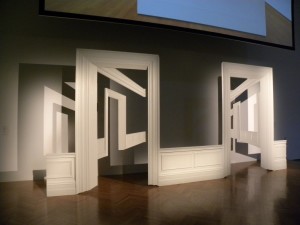

and the entrance to an empty museum “Views from inner to outer compartments”

Each of these components form a part of the narrative in Raad’s performance, which he claims refers to the construction of the history of art in the Arab world, as he puts it.

The largest and most complex component, is the wall projection “Translator’s Introduction: Pension arts in Dubai” It is this projection and performance that I will focus on here with briefer reference to the rest of the second floor installation at the Museum. (There is also a retrospective of his earlier work on the third floor component of this major retrospective.)

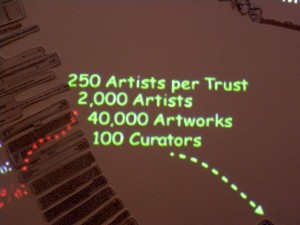

Raad’s narrative of the large tableau began with an account of the Artists Pension Trust, a real organization that signs contracts with artists who donate works to a privileged investment plan. (Prominent art historians are listed on its Advisory Board online).

But Raad’s real point is not this huge contemporary art collection, but the basis for the determination of value in contemporary art for such a fund. Who will buy the work and why? Financial investors need to have a basis for their decisions. He digs into its background and discovers that the tech workers of the parent company are former Israeli military intelligence officers. That company is owned by another company that combines risk management and algorithms: it analyzes data such as auctions, art language, and even color, in order to determine what affects the value of art.

The chilling result of Raad’s research is that the value of art is being determined by the use of a group of hedge fund experts in risk management. The sudden emergence of support for contemporary Arab art in the last ten years is embedded in this project. In addition to art work, the APT collects curators and art historians as advisors, who are well paid for their time. They create exhibitions and reassure investors of the value of the art.

In the tableau, these analysis are outlined in detail, with cut out biographies for about a dozen tech workers and their connections to the Israeli military.

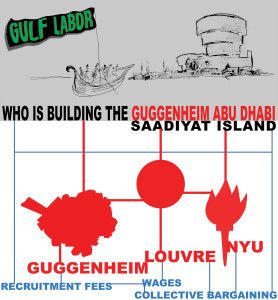

This arc is part of a larger arc that connects this intersection of art and money to the cultural explosion on Saadiyat Island in Dubai, where five institutions are being built to house gigantic collections of contemporary culture by five super famous architects. Dubai is investing in culture on a monumental scale. The cultural institutions include the Louvre, the Guggenheim, New York University, and, in collaboration with the British Museum, the Zayed Museum about the cultural history of the United Arab Emirates. Saadiyat, ironically, is very close to sea level, so it will certainly be flooded early in the rising sea levels that await our abuse of our planet, of which this mega “cultural” project presents itself as a dazzling example.

One has only to look at Gehry’s absurd design for the Guggenheim to see the inflated character of the project. The ludicrous design almost seems to be Gehry’s own joke as his response to this inflated, overwrought and contrived cultural endeavor.

The project on Saadiyat Island combines with high end hotels and other “amenities” (New York University! A golf course!) to present a complete “cultural” history and experience. The description of, for example, of what will be in the Louvre Dubai, is so vague as to be a parody of museum language and curatorial approaches.

In fact the whole project is a parody, and Raad’s performance is a parody of it as well. The crazy moving tableau suggests, as curator Eva Respini has amusingly suggested, a wild distortion and aberration of a flow chart, harking back to that early effort to order art history by Barr. But it is also, on some level, a frightening story.

Raad’s larger purpose is to call our attention to the ways in which contemporary art history and culture can be fabricated out of nothing, out of an empty sandy island. Another part of his installation speaks of how the colors (being analyzed for value, see above), are now hiding. We see a wall of seemingly empty squares, which are in fact, enlarged segments from publications, in which the colors are choosing to hide in the margins, to avoid their algorithmic fate.

Another segment presents a miniaturization of Raad’s entire career in a model of a contemporary art space in Lebanon, a huge space, unimaginably larger than previous spaces for contemporary art in Beirut.

His work, though, is shrunk to tiny proportions. Again, this is a psychological experience, based on anxiety about what is happening to Arab art. Finally, a wall appears with Arabic names one of which is splattered with red paint, a name of an historic artist which has been misspelled. Raad excavates his career from scraps of old articles, perhaps in an effort to begin a “real” history of Arab art. The last part of this segment of the exhibition includes an “entrance” to a museum, an empty museum, which we cannot enter, and Raad details how it prevents an Arab artist from entering.

But there is even more to this contemporary meditation on the history of Arab art in the Middle East.

Up on the third floor, a corridor and a single small gallery includes 3d prints of Islamic art from the Louvre, some of which is metamorphosing into Byzantine art before our eyes. These images are based on Raad’s actual research in the Louvre of the Islamic collection and his fantasy of what happens to this art when it is shipped to Dubai. It metamorphoses, it becomes something else.His installation includes 3d jet prints of objects from the Louvre. Part of the Louvre collection is destined to be exhibited in Dubai.

Raad’s fantastic installation, in the end, is a terrifying exposure of the interconnections of art, power, money, pretension, art investment, culture as a cloak for political aspirations, and of course, the invention of contemporary art history in the Arab world.

At the same time, if we look at it all in another way, we can believe that the Arabs are simply trying to counter their image as “terrorists” to suggest that they are cultured intelligent people with a history hidden in the middle of the oil soaked desert.

The Gulf Labor Coalition is exposing the slave conditions in which the workers who are building all of this culture are living.

Raad is part of the Gulf Labor Coalition, but has been banned from returning to the UAE. These activists expose in New York and elsewhere the abysmal gap between the treatment of workers and the pretentious arrogance of the cultural institutions and their elite brands.

Raad’s installation moves into the heart of Middle East politics, its inequalities, its wars, its culture, all in the form of a parody of museum installations.

This entry was posted on February 23, 2016 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art in Beirut, Art in War, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.