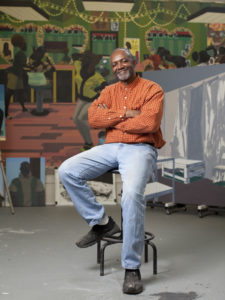

Kerry James Marshall Maestro and Shaman

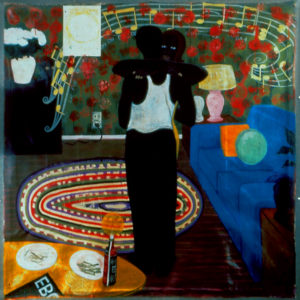

Kerry James Marshall. A stunning retrospective exhibition at the Met Breuer featured room after room of his magnificent paintings, filled with magnificent people who are very black, blacker than real African Americans to the point of being confrontationally black for a white museum audience. These black people are how white people see black people, all one shade of darkness, an absence in the landscape, a trope of fear, a criminal, a threatening presence. Black person coming? Time to cross the street.

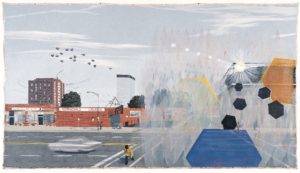

But wait. These black people are simply living their lives, they are living in the housing developments that were built to provide a utopian future for impoverished people. The developments had lawns and playgrounds. The city has public parks to play in. That was enough wasn’t it? As in my photograph taken not far from the North end of Central Park in New York City, these were “wonderful communities”. So what are these people doing?

As in my photograph taken not far from the North end of Central Park in New York City, these were “wonderful communities”. So what are these people doing?

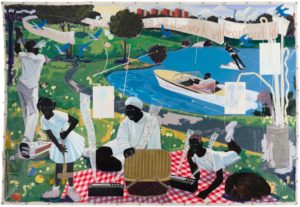

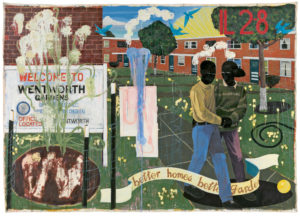

They are enjoying life, they are walking hand in hand, they are riding bicycles, they are celebrating Easter. But who are they looking at? Usually, not each other. Or if they do look at each other, their eyes also seem to look out toward us at the same time, as in the Wentworth Gardens painting “Better Homes, Better Gardens”. They seem on guard, as though these pastimes are somehow going to be taken away at any moment. They are frozen, not moving, not joyful, not relaxed. They live in the grip of a dream of life, a life free of surveillance, crime, dirt, broken elevators, overflowing washing machines, petty thieves, poverty, gangs, children who die, husbands who vanish or get shot, wives who die. No, none of those aspects of life are depicted here, but they lurk just under the surface.The surface paint patterns, suggesting overgrown flowers or fountains slightly out of control, are more like graffiti or something more generic, simple defacement.

Children have dates on them, the date of their death.

Children have dates on them, the date of their death.

Fathers dig holes – are they graves? The lid of a picnic baskets becomes a shield. These people are striving for life, they are taking what is offered as much as they can, but it can disappear any minute. And the disappearance is because of who these people are staring out at, outsiders, white people, police, drug dealers. Invisible in these paintings, next to these ordinary people trying to live their lives, are all those threats. These are Kerry James Garden Series.

Fathers dig holes – are they graves? The lid of a picnic baskets becomes a shield. These people are striving for life, they are taking what is offered as much as they can, but it can disappear any minute. And the disappearance is because of who these people are staring out at, outsiders, white people, police, drug dealers. Invisible in these paintings, next to these ordinary people trying to live their lives, are all those threats. These are Kerry James Garden Series.

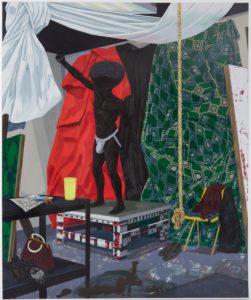

In his retrospective, racism, darkness, fear, death lurks behind every single painting, sometimes obviously, sometimes more subtly. Marshall honors African American as well as white heroes, he memorializes those who have died in the cause of freedom for slaves, or former slaves. He knows his history, and he honors those who died such as the Stono Group ( a little known slave uprising in 1739)and Nat Turner, much less lionized than the white John Brown.

Nat Turner with the decapitated head of his master shakes up a white viewer. We are used to dead “others” or historic long time ago dead, but here is a white “master” from the US decapitated by an uprising slave! Wow.

Nat Turner with the decapitated head of his master shakes up a white viewer. We are used to dead “others” or historic long time ago dead, but here is a white “master” from the US decapitated by an uprising slave! Wow.

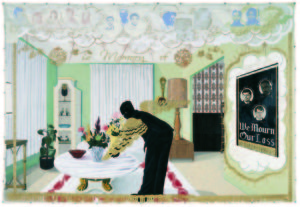

But Marshall confronts other prejudices. He gives us love. We white people do not think of African Americans as enjoying love amongst themselves because we are obsessed with their sexuality as a threat to us. The black white divide has always “swung” on that fear. Marshall not only gives us loving couples, he gives us eroticism, black naked women and men, he gives us romance.

Last he gives us art, he gives us art history, he brilliantly quotes our most famous historical icons, Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, Edouard Manet, Diego Velazquez, not to mention more recent artists. He quotes styles, plays with decoration, minimalism, text, staging. Much is made of his painting in the catalog for the Breuer exhibition. On and on they write about the paint, the paint, the paint. And the art historical references, and the contemporary references, almost always to white artists, as though that will legitimize the work.

But the central theme of Marshall is to correct an absence. Absence of the black body as subject, as human, as living, as romantic, in the history of art, in museums, in our lives. And the underlying sea of references, about which we could go on layering ideas all day, are the celebration of African religions, mysteries, symbolism, right on equal footing with all those nice white guy quotes. The integration of these two worlds is what Marshall seeks. ( This is the only mystical work included in our press images)

Part II

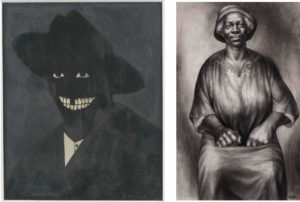

It was absolutely amazing to me that all the experts writing repeatedly in the catalog about the importance of A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self 1980 never mentioned that it gives back to the white gaze what we see as white people, which is caricature, shadow, teeth, eyes. That is the reason for the title.

We do not see the person, the humanity, the complexity, the dignity (as suggested in the Charles White painting above, Marshall’s most important mentor).

The painting is significant not as a portrait, but as a manifesto, an absolute expose of prejudice. Marshall’s black on black paintings of “invisible man” based on the Ralph Ellison book as he has said repeatedly, emphasize that inability of white people to see black at all as anything other than one single dark place. But as you look harder into these paintings many details emerge, subtleties, nuances. That is what we white people all need to do. (Notably our press packet included not a single one, the self portrait came from the internet)

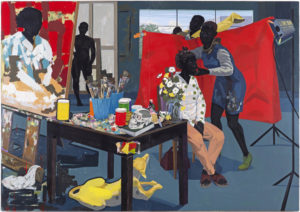

In Untitled (Studio), as Helen Molesworth points out, the artist is absent. The models are present, the act of making art is present. The wonderful vocabulary of references and styles is present.

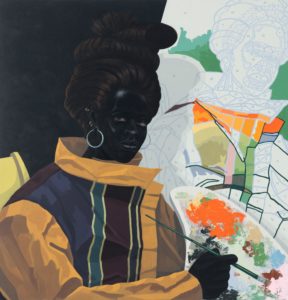

The artist is present in the “untitled” portraits of artists, but again we see the caricature of white prejudice, the traditional portrait format is exaggerated, large torso, direct gaze, holding a giant palette, an irrefutable presence; but behind lurks a paint by numbers canvas. If we cannot see humanity in African Americans, we cannot see the enormous subtlety of their art either. So he gives us the artists and the paint itself, because we can understand that (and understand we do, endlessly reveling in those piles of paint on the palettes, wow, look, see, paint). And of course the artist had a lot of fun painting these works as well.

The artist is present in the “untitled” portraits of artists, but again we see the caricature of white prejudice, the traditional portrait format is exaggerated, large torso, direct gaze, holding a giant palette, an irrefutable presence; but behind lurks a paint by numbers canvas. If we cannot see humanity in African Americans, we cannot see the enormous subtlety of their art either. So he gives us the artists and the paint itself, because we can understand that (and understand we do, endlessly reveling in those piles of paint on the palettes, wow, look, see, paint). And of course the artist had a lot of fun painting these works as well.

Marshall is a subtle, brilliant trickster. He has duped white eyes into looking at our own fears of darkness, with stunning paintings that elevate the humanity of the African American experience for us to see, embedded in delicious colors, textures and drawings, dizzying arrays of styles, all of it simply at the service of seducing us into actually seeing that African Americans are real people.

That is why Marshall is unique. Dozens of African American artists have presented African Americans in film, photography, painting, sculpture ( as seen for example in the 1994 exhibition “Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art”. The Whitney held it just before Marshall emerged in the late 1990s. The work is subtle and sophisticated, in some cases, perhaps we can say it is cloaked, as in the work of Lorna Simpson for example, with all those backs and fragments, no faces.

But to what extent did white eyes face their own prejudices in looking at that work. Not at all. In fact often our expectations were reinforced when we saw criminals or large black sexual organs.

Marshall leads us in through art history. He allows us to wallow in our old fashioned, comfortable modernist references. Look, there is Manet’s cat, or there is a skull out of Holbein!!! Flat paint samples play with space!!! But as we wander through these references, we cannot avoid the people, the life, the layers of experiences

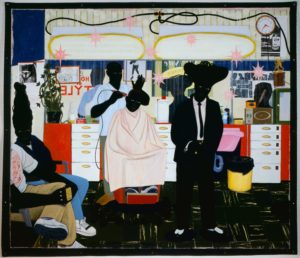

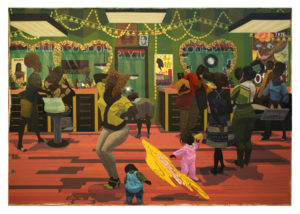

For that reason, certainly, the two paintings of the beauty parlors: De Style 1993 and School of Beauty, School of Culture 2012 are the greatest gifts that Marshall has given us. They allow us white people into a place that is almost a sanctuary of black power, on a par with church (which he does not represent, although spirituality appears often). And as we roam through it, we white people suddenly realize we have never been here before, and we actually do not belong here. But we can acknowledge that here is real life, real culture, real people. And it is the white ideal that in the end is a mirage, an odd phenomenon, as the small children point out in School of Beauty. Here people really are living their lives on their own terms. No one looks out.

This entry was posted on March 1, 2017 and is filed under African American history, American Art, Art and Activism, art criticism, Art of Democracy, Black Art, Black Panthers, Ethnicity, Uncategorized.