Migration Then and Now: A European and UK Perspective

“No Turning Back” Migration Museum Project, London

Migration! What an ongoing catastrophe today. People drowning by the hundreds in the Mediterranean trying to get to Europe, people stranded in Calais, France who were trying to reach the UK; refugees stuck on the Island of Lesbos or in Northern Greece for years. Thousands of people in a camp outside of Paris, the EU cruelly closing its borders in violation of its principles, and in the UK, there is Brexit, anti immigrant fervor as ignorant and vehement as that in the US.

One of the best books I have read on this subject is The New Odyssey by Patrick Kinsley. As a Guardian reporter he was supported to go to the places where migration from Africa is occurring, to talk to smugglers, to follow people in Greece to the border of the EU

(both before and after it was closed), to meet people of all ages and talk to them and to point out how the EU policy is completely ineffective and inappropriate. He followed one man’s journey from Africa to Sweden.

The Migration Museum Project, based in Lambeth, South London, offers an historical perspective on UK migration. Its current exhibition, “No Turning Back” chooses “seven migration moments that changed Britain.” Although the exhibition is deliberately non chronological, I will put them in historical order.

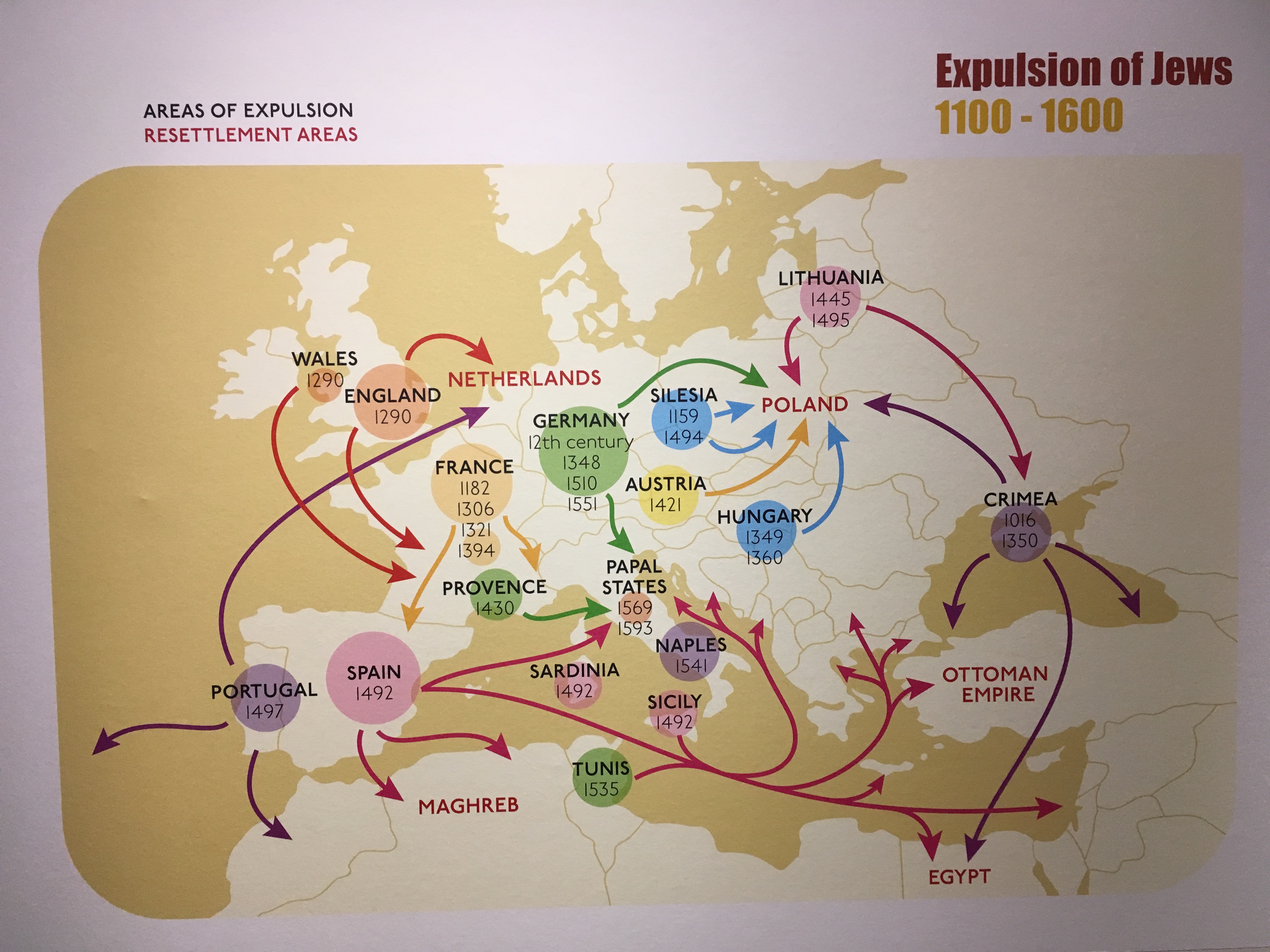

Multiple expulsions of the Jews 1100 – 1600

The earliest event, the expulsion of the Jews in 1209 (this was of course an emigration, not an immigration) followed on years of discrimination.

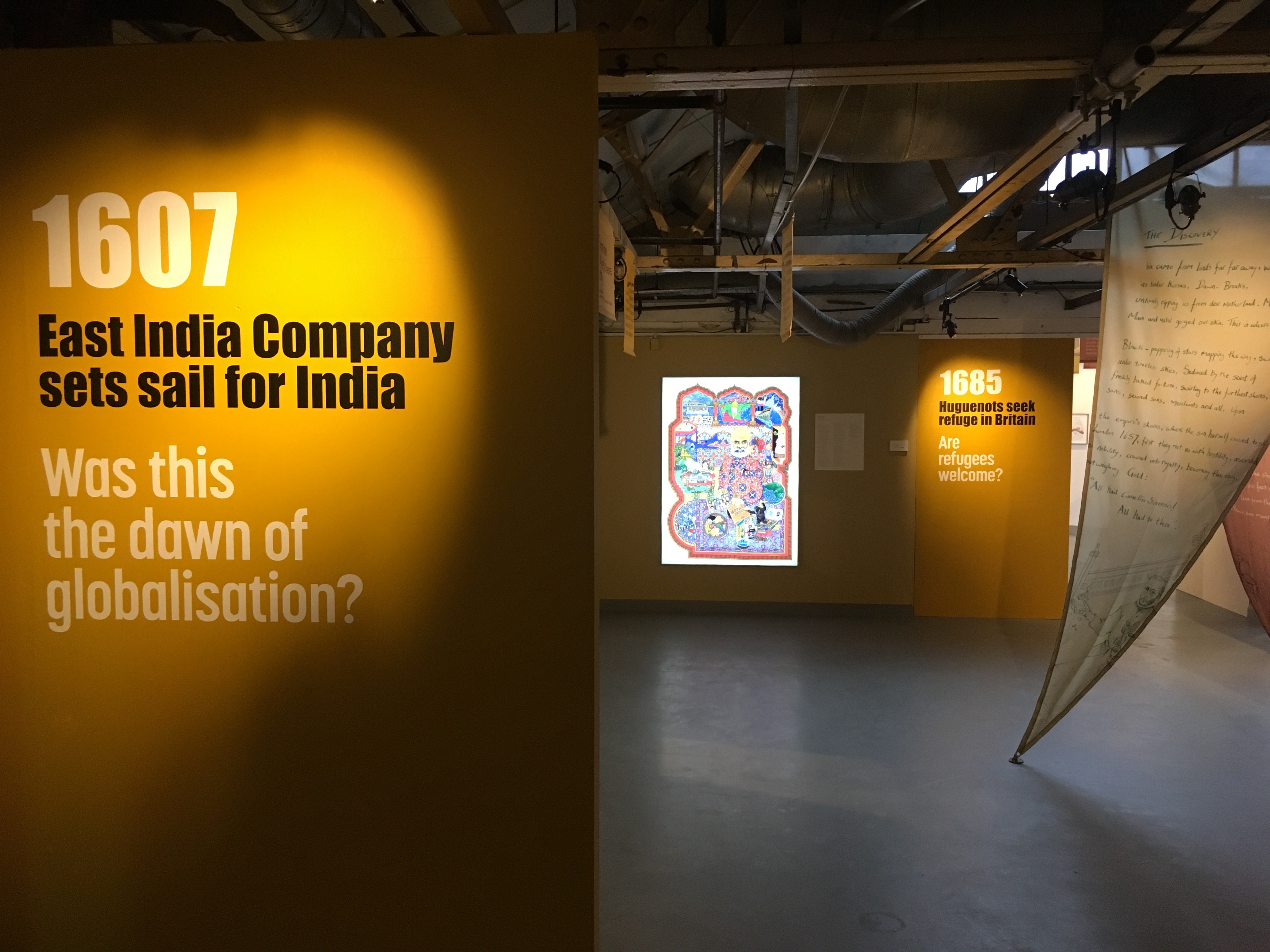

1607 is the year that the East India Company first went to India leading to centuries of complex migrations to and from England. This exhibition includes the stories of individuals and families of Anglo Indians, Gurkhas, and Lascars, three groups that participated in the British colonial project in different ways.

A huge immigration of Huguenots came to Britain in 1685 to seek refuge when they were expelled from France.

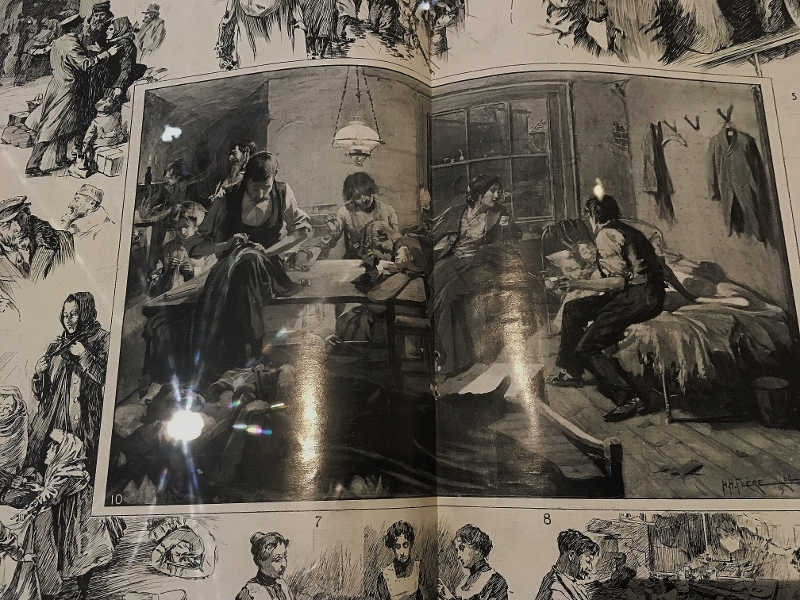

Jewish sweat shop workers and immigrants 1900 London

The Alien Act of 1905 limited immigration with intense xenophobia campaigns, mainly also targeting Jews who were coming from Eastern Europe to escape pogroms.

From a different perspective, the first passenger jet flight in 1952 profoundly altered migration from the tradition of slow journeys on ships (although today we have a sad return to sea travel, and even the most ancient migration, by foot).

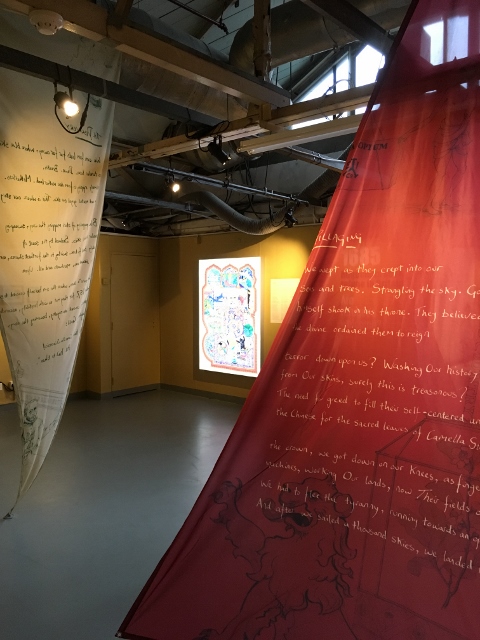

Foreground sculpture by Roman Lokati of refugees from World War II, Basque Country ( his own country) , and Syria. Quotes by refugees on banners

Offering a positive event that pushed back against racism, Rock against Racism in 1978 was a grassroots resistance movement to racism in the music community. It inspires us with its creative means of exposing and countering prejudice.

The last “turning point” 2011, when the “census reveals rise of Mixed-race Britain,” leads us to Brexit. Liz Gerard charted the rising racism in newspapers in the UK month by month leading up to the Brexit vote.

The final segment on mixed race Britain leaves no doubt as to the situation today. Two photographic art projects, Humanae by Angelica Dass, and Mixed by Andrew Barter both celebrate the diversity of contemporary Britain.

What makes the Migration Museum Project exciting though is not only their dynamic and multi dimensional perspective on migration as a process, but their embrace of community.

Mixed by Andrew Barter

Humanae by Angelica Dass

The museum invited these and other contemporary artists to create work pertinent to each turning point as well as organizing workshops, public lectures, and other events. Banners on the ceiling with potent quotations pair with migration stories from the public on small cards against one wall. Children made small ships.

The first “moment “ in the installation, the 1609 founding of the East India Company seems to sail into the gallery with actual sails hanging from the ceiling by Nick Ellwood and Kamal Kaan’s , “And after we’d sailed a thousand skies, “ On each sail handwritten poetry by Kamal Kaan invokes the omnipotence of tea.

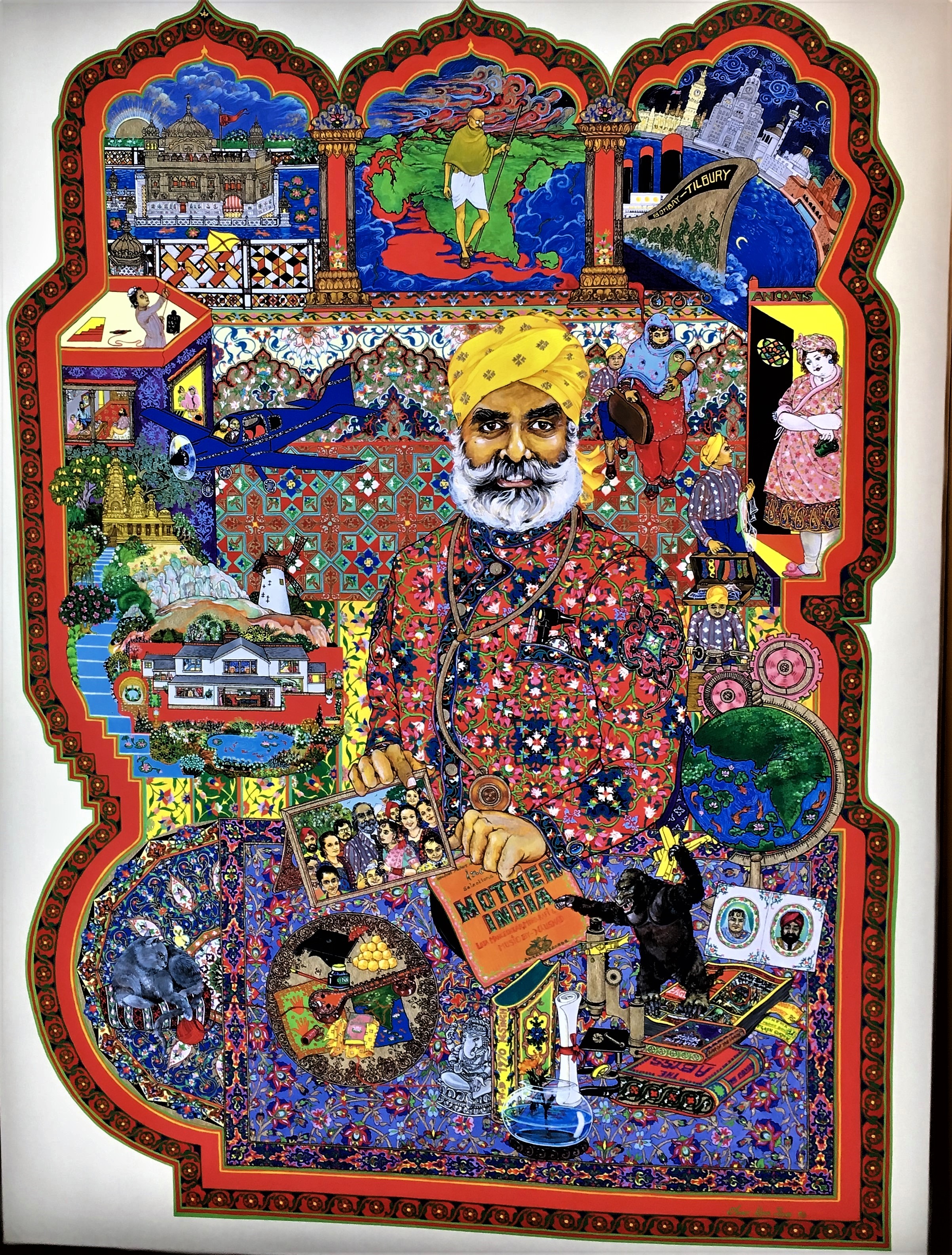

In the same section, and underscoring the complexities of the British Empire’s colonial enterprise with respect to migration, “All that I am,” by the famous Singh Twins features a portrait of their father with their family history of migration in vignettes surrounding him in both traditional and contemporary styles.

The Migration Museum Project have created several exhibitions in temporary venues including “100 images of Migration,” chosen from 100s of photos submitted by the community, “Germans in Britain,” emphasizing an “invisible minority” and “Keepsakes” that invited the community to tell stories about one object that spoke to them of their personal experience of migration. These three exhibitions all took place in community settings, and each venue reached a new audience. Another pioneering exhibition about the Calais refugee camps called “Call Me By Name- Stories from Calais and Beyond” in June 2016, held in Spitalfields, closed the day before the Brexit vote.

Calais, France – November 7th 2015 – People chatting in an Afghan bar and restaurant.

Ph.Giulio Piscitelli

A play called The Jungle, that we saw the night before we left London, was set in the Calais camps in France before they were destroyed in October 2016. Right before that point they held more than 5400 people of whom 445 were children, 335 unaccompanied. But this play was more than set in the camps, we were in the camps ourselves, all seated at tables or on the floor in sections various identified as Iran, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan etc.

The playwrights Joe Murphy and Joe Robertson had created a theater in the camp, The Good Chance Theater, for the refugees to perform and write plays. They have just started another theater in the huge refugee camp outside of Paris.

The actors, by far the most diverse cast I have seen, represented people from the different countries, and they ran around on the tops of the tables and platforms where we sat. Vociferous, desperate, joyfully singing and dancing, tragic, they recounted the building of the camp from nothing, into a city with bars, cafes and a famous Afghan restaurant .

Their dream was to come to the UK, but since they could not, they created a city out of nothing. Then they were destroyed, “for sanitary reasons” and dispersed. The delicate balance of community and conflict has been underscored recently as an outbreak of violence between Afghans and Kurds in a subsequent camp led to the desperate refugees setting it on fire. Today there are many thousand refugees in a holding camp outside Paris. The situation is chaotic and desperate. UK and France are planning to spend millions on a massive barricade in Calais. Why not use that money to enable refugees to find a new home?Many children from the camps are still wandering.

Arabella Dorman Suspended St James Picadilly December 2017

In order to call attention to the plight of refugee children, Arabella Dorman takes the spectacular approach of a giant hanging installation at St. James Church, Picadilly. 700 items of children’s clothes, collected on the island of Lesvos, hang above our heads, a single shoe, an African fabric dress, a shirt, a jacket, pajamas, they seem to fly like angels in the air.

The installation evokes children playing, running, falling, holding hands. I saw it as I listened to a Mozart concert in the church and felt my extreme privilege. Will any of these children ever have the luxury of listening to a Mozart concert or to play one? The installation is intended to remind the UK government of its commitment to take 400 unaccompanied child refugees, a commitment which they have only met by 50 percent.

Ai Wei Wei’s amazing film The Human Flow overwhelms us with its scale, and scope. The filmmaker visited 23 countries over the course of a year. The film combines interviews with migrants that covers many topics from the wretched conditions in the camp in Northern Greece where thousands are stuck unable to go on to Macedonia, to the airport in Berlin where small compartments house hundreds of refugees, who are isolated from society and “bored” as one young girl states.

The people interviewed always spoke on their own without interviewers or a question, but Ai Wei Wei appeared throughout the film in various capacities, helping refugees off a boat, getting his head shaved, talking to border guards on the US border. The only actual scene of the drivers of migration was a scene of bombing near the end, but the devastation spoke loudly of ruined homes and communities.

The EU crisis has its roots in the destruction of war and climate change both driven by the developed world, and particularly imperialism. It is responsible for these refugees. Who would leave their home unless they felt they could no longer live there. To take the perspective that these desperate people must be detained or deported is a betrayal of the basic principles of humanity.

This entry was posted on January 16, 2018 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, Migration, Uncategorized.