Prisons and Detentions: A Perspective from the UK

Part I The Darks

Before the stylish Tate Britain, the Millbank prison rose forbiddingly on the same site from 1816 to 1890. In an extraordinary audio guide, The Darks Ruth Ewan and Astrid Johnston take us around the original prison, the utopian principles behind it and the realities of the grim conditions inside it .

.

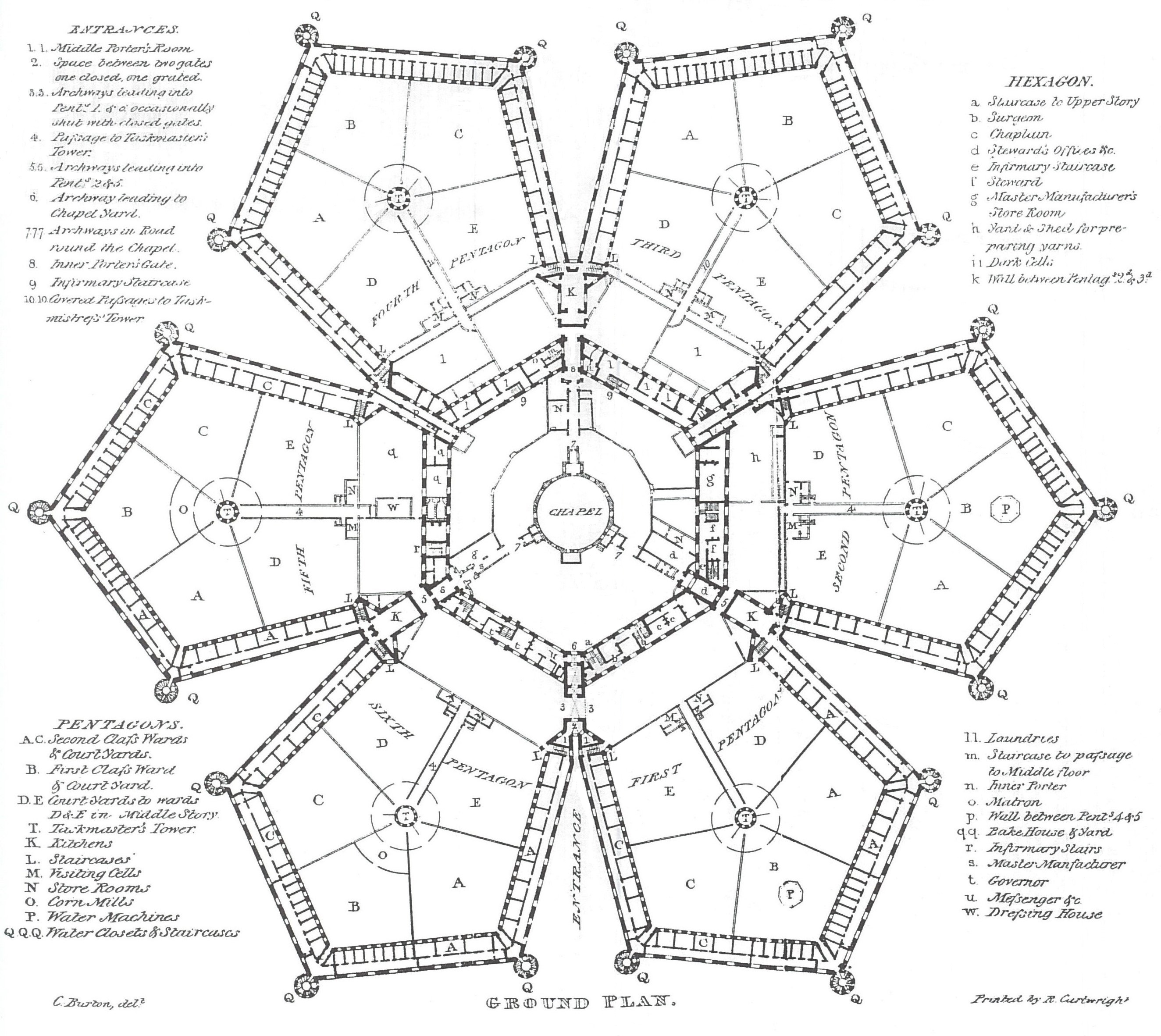

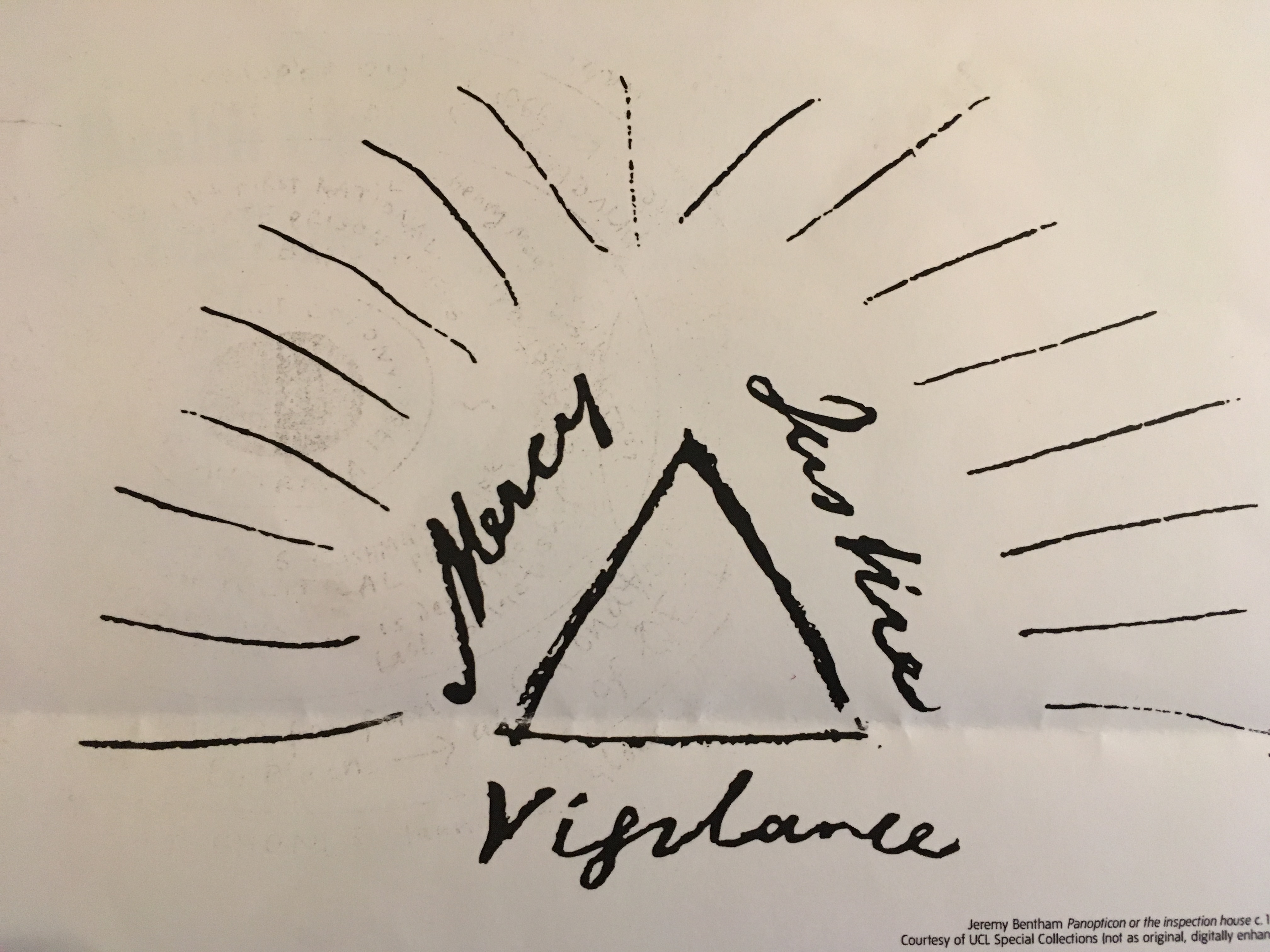

Jeremy Benthem Panoptican or the Inspection house c 1787

First we hear of the idea of two prisons, one real, one imaginary. The imaginary prison was the idea of Jeremy Benthem who imagined the panoptican, a single inspector able to see everyone at once, but the prison was meant to be iron and glass, and an improvement over existing prisons. Benthem’s vision of surveillance has of course survived and today we go way beyond his idea of the visible eye, to unseen surveillance everywhere.

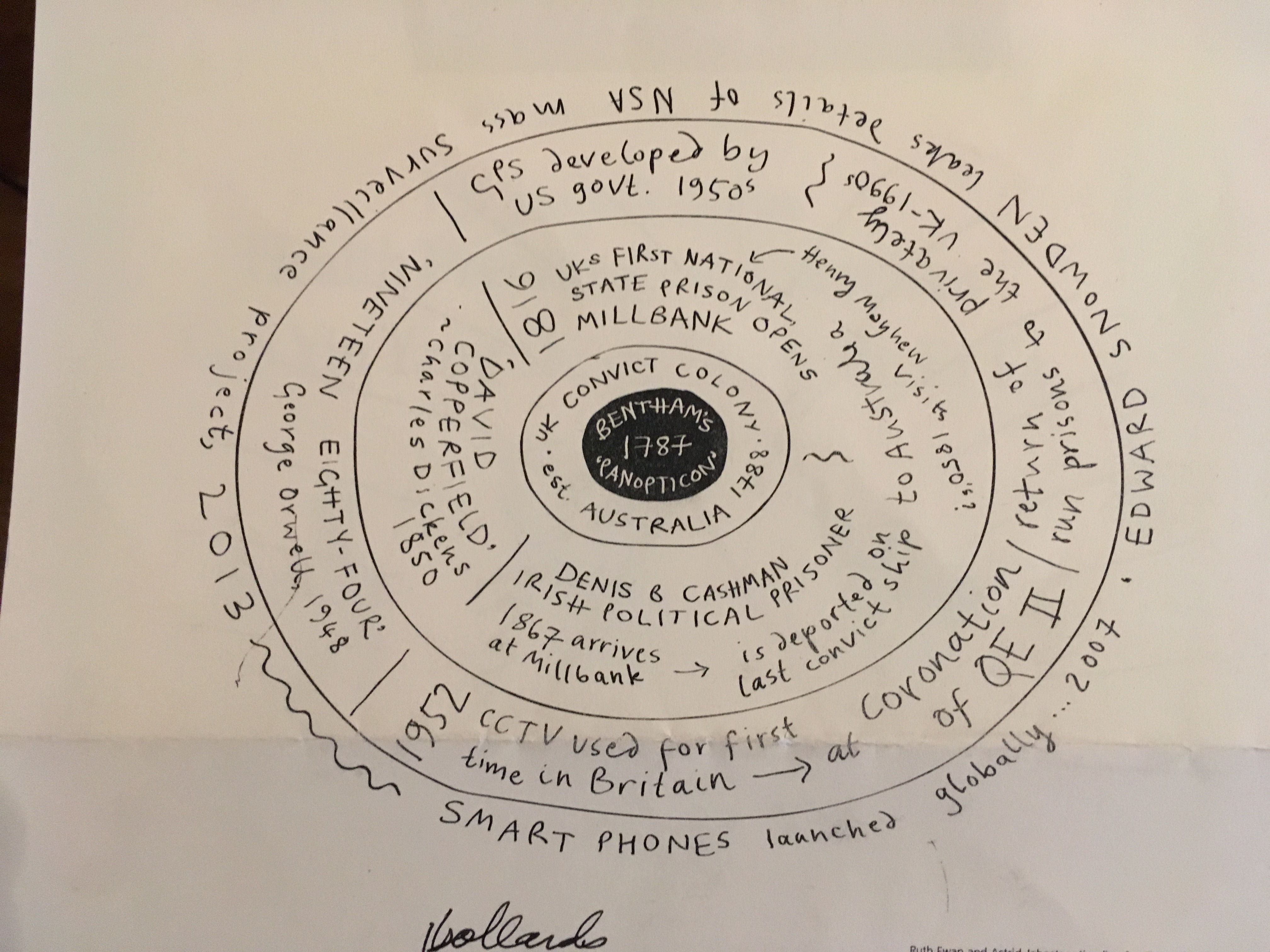

The tour is accompanied by a chart of concentric circles that lead from Benthem’s 1784 panoptican vision to surveillance by smart phones.

On the tour we see the few remnants of the original prison such as this bollard, and a “moat”.

Originally marked the steps where prisoners boarded boats to be transported to Australia

We hear the voices of prisoners and learn of the horrendous conditions inside. Well known authors such as Charles Dickens in BLeak House described the prison. Henry James in The Princess Casamassima describes the gruesome infirmary.

The Darks is a reference to the darkness of the punishment at the lower level. It is the antithesis of Benthem’s idea of a transparent structure of glass that would reform people through the power of reason. Instead a turreted labyrinth was built inside and an octagonal wall with 16 acres of grounds.

The land originally was a burial ground for plague victims, purchased by Benthem to build the prison at a time when prisoners were held on decrepit ships on the Thames for transport. In the late 18th century colonies were in revolt and the US closed its borders to prisoners, so the first holding penitentiary in the UK was completed in 1816. The prisoners were supposed to be deported to Australia, but many remained there in miserable conditions, or died there.

Today we have the elegant Tate Britain whose central interior space still echoes the panoptican .

Part II Detention Centers in UK today

Brook House Tinsley House/ Immigration Removal Center, Perimeter Road South, Gatwick Airport, West Sussex, England copyright Rob Stothard

The practice of detention continues in the UK. In much smaller numbers than in the US, it is nonetheless equally inhumane, run by the same corporation, GEO, that runs US detention centers. Rob Stothard and Silvia Mollicchi have written Removal, A Short Guide to the United Kingdom’s Immigration Detention Estate.They photograph only the outside of “holding facilities” “short term holding facilities- Reporting Centre”(4), “pre departure accommodation” (1)and “immigration removal centers” (7)

The photographs give us innocuous country lanes, fences, office parks, and houses. The anonymity of the sites is intentional, and the artists did not enter them or photograph any people, although each site is accompanied by a detailed description and often the frequently tragic story of a particular detainee. We have been reading frequently in the Guardian about people who have lived here for fifty years who are being rounded up and deported. These people came at a time when papers were not required, as part of the Commonwealth.

Now they are grandparents and shocked to be sent off to detention and often back to a country they don’t even remember.

In another approach to detention, Greg Constantine photographs “stateless people” around the world, in the exhibition I saw “Nowhere People,” sponsored by the UNHCR, he focuses on people in permanent detention in the UK. They cannot go back to where they came from and they cannot stay in the UK. There are 10 million people around the world who live without a nationality, over 75 percent are from minorities such as the Royingya, the largest stateless group.

In the UK they are in permanent detention.

Nana Varveropoulou in collaboration with detainees 2014

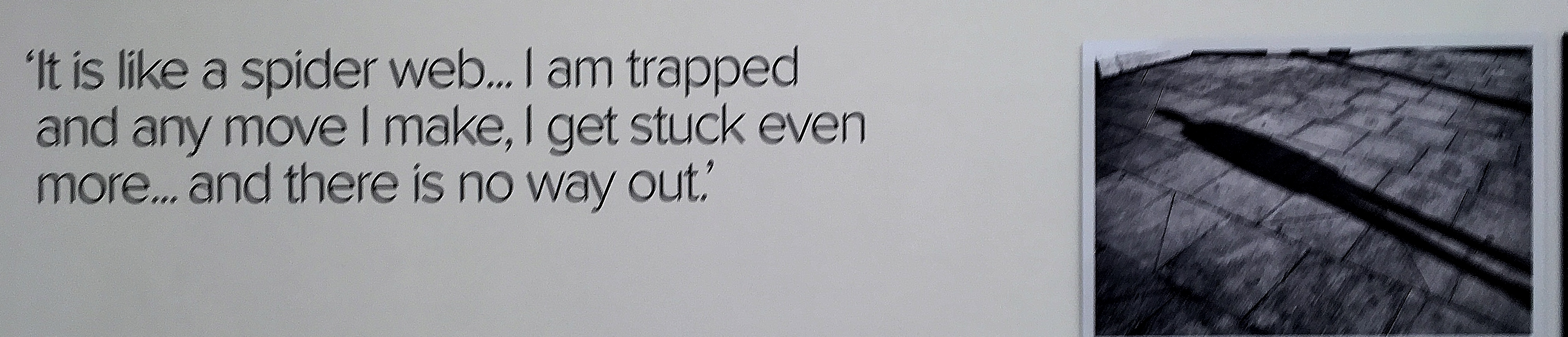

Nana Varveropoulou succeeded in getting inside a detention center at Colnbrook from 2012 – 2014 to do a workshop. That led to collaborating with detainees on a photographic project documenting their lives called No Mans Land. You can see her account of it in the article from the Guardian, as well as the images on her website.

These artists make the invisible visible. They refuse to let a human tragedy be swept aside in the midst of the endless focus in British news on Brexit.