Carletta Carrington Wilson’s “letter to a laundress”

Carletta Carrington Wilson, Jack Delano, Tenant Farmer wife washing clothes, Greene County Georgia, June 1941, reprinted by CCW for poster design by Al Doggett

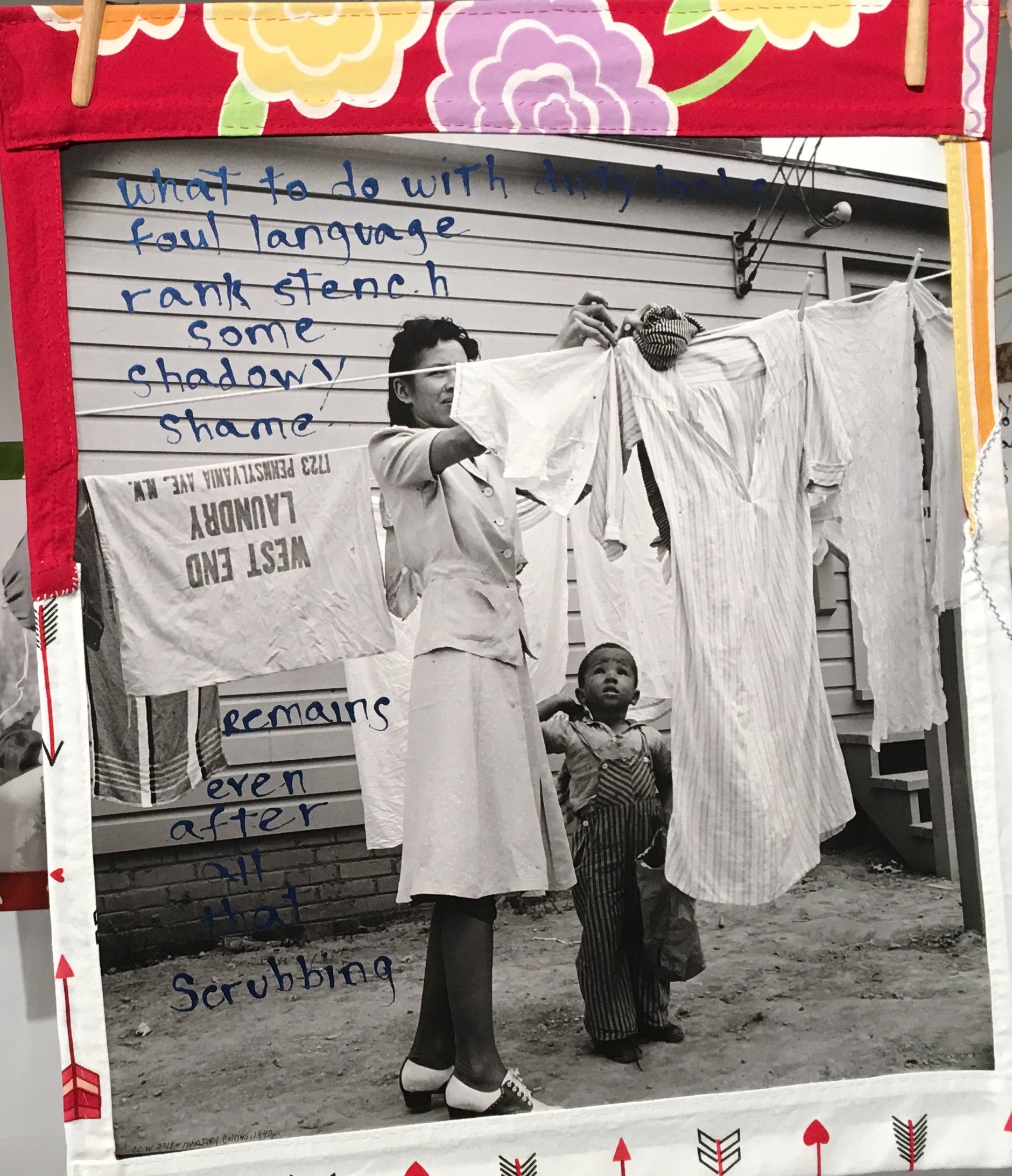

Carletta Carrington Wilson addresses her “letter to a laundress” to her great great grandmother, but her profound photo/poem installation currently on view at the Kittredge Gallery in Tacoma (only until September 29) honors the work of all those who, in her words, “took in wash.”

She found photographs of anonymous laundresses in the archives of the Farm Security Administration, most of them taken in the late 1930s by such well known photographers as Dorothea Lange, Marion Post Wolcott and Russell Lee.

The “letter” is a poem written in blue script on the photographs, and recited by the artist in a pod cast as we view the work.

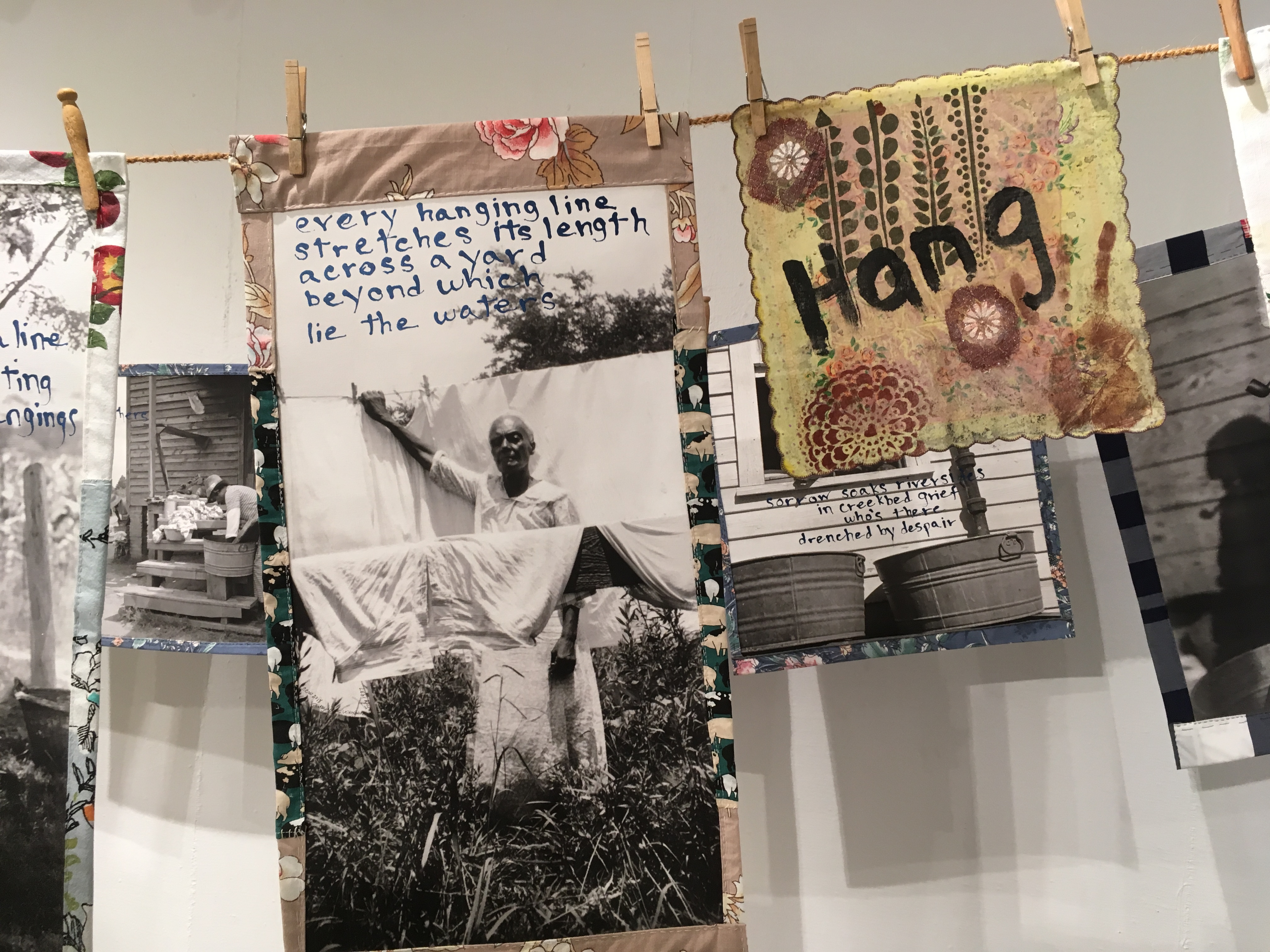

Mounted on fabric, the photographs are pegged to a line, and hang above our heads. As we walk between three lines of closely packed “laundry” the poem unwinds, describing, the many steps of doing laundry before the advent of machines and drip dry fabric.

Carletta has identified ten steps

each with a single word:

Wash Soak Starch Wring Boil Pin Rub Scrub Hang Press.

Photograph on the right “you taught her well” photograph by Doris Ullman Negro Girl Ironing, Place unknown 1938

“what to do with dirty looks” Marjory Collins Arlington Virginia FSA trailer camp project for Negroes hanging out washing in front of the community building, April 1942

deftly rubbing, rubbing, ” Russell Lee Wife of FSA client, former sharecropper, Washing clothes in front of old cabin, Southeast Missouri Farms, May 1938, right photograph “wringer iron holder Dorothea Lange, Washington facilities on a Greene County Georgia tenant farm July 1937

The photographs are arresting, suggesting the real labor of doing laundry and how it evolved. Some of the photographs are actually from the late nineteenth century, early washerwomen, using a washing stick to stir laundry in a tub, others are using a washboard, that iconic object now seen only as a relic (several are included in the exhibition).

Left no title, right “oh mothers,” Dorothea Lange Washing Facilities on a Greene County, Georgia tenant farm July 1937

The separate steps, such as an iron wringer

now so lost to us, appear in these FSA photographs.

The women rarely look up or out, never at the camera, the photographer. We have all types of women from those dressed in a muslin shift to elegant women in suits and shoes with heels.

Carletta Carrington Wilson deeply feels words, their meanings, double meanings and symbolism. Thus here, as offered by the artist, is a shift from laundry to something more sinister:

“hoist baskets tote tubs lug those loads every bundle extends a line

a line awaiting a line awaiting its hangings.” And suddenly as Wilson wrote the poem, she realized the double meaning of hanging as also lynching.

“every hanging line” National Photo Company Collection, photographer not identified: Orelia Alexia Franks, ex-slave, Beaumont Texas, July 3, 1937

As the artist said in a lecture “The lines of the poem lead the reader away from the mundane duty of washing clothes to a disturbing image of lynching. Thus, we are led into the awful reality that links these women beyond the ordinary task of laundry.

“Post emancipation, in the late 19th and early 20th century there was a rise in the number of lynchings in the south. These mothers, sisters, aunts, grandmothers, cousins and friends knew, were related to, heard of, witnessed and buried someone who had been lynched. They, also, washed the clothes of someone who participated in a lynching. I was just speculating, but this was confirmed by a woman who spoke to me after one of the artist talks”*

This exhibition includes other intense works as well: across one wall is a series of fabric works called “field notes” from 2014 with Carletta’s trademark layers and meanings hidden in their patterns and textures.. You can spend a long time exploring these works, which are, as the artists suggests, like landscapes. One of her themes in her work is the “text of textiles” the steps from cotton into cloth and the metaphors that emerge from fabric.

fieldnotes wrap my hand tight

field notes woke ‘fore day

Then there are simple cut out house shapes, what the artist calls “wordless books.” in a series called “knot my name haint my house”. They refer to the fact that 90 percent of enslaved people were illiterate. The blue around the doors is called ” ‘haint blue’and was used to deter ghosts” the artist explained.

Carletta Carrington Wilson from the series “knot my name haint my house”

On one wall a “knotted line” again has double meaning, the names are (k)not names, but the names given by slave masters, here taken from a plantation inventory. The artist elaborated

“The idea is that once a person become enslaved their lines of descent are knotted. Each time a person is sold, with each name

change and change of place of bondage the loss of knowledge of familiar ties becomes, increasingly, knotted and unknown.”

Carletta Carrington Wilson “the knotted line” Photo by Mark Frey

Photo by Mark Frey

The “blood knot” lies below “2 resist dying”, another title with more than one meaning. two indigo blue wall hangings in dye resist. The artist describes the work “2 resist dying” as referring to both the resist-dye process and, also, that of a man and woman resisting their enslavement.

The artist explaining the work “2 resist dying” Photo by June Sekiguchi

Underneath is a “blood knot, “a tangled pile on the floor invoking the intermixing (knotting) of blood among people involved in the slave trade. The artist specified “The “blood knot” represents the knotted blood lines of Africans, Europeans, Asians and Indians as a result of the global trade networks formed during the transatlantic slave trade. ”

Carletta Carrington Wilson poet, collagist, historian, one of the most intriguing creative minds I have known. Here’s hoping this exhibition can move to a major museum soon.

*Thank you Carletta Carrington Wilson for sharing this text and other information and images for this blog post.

This entry was posted on September 7, 2018 and is filed under African American fiction, African American history, American Art, Arican American history, Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Civil War, ecology, Uncategorized.