Charles White: Humanist

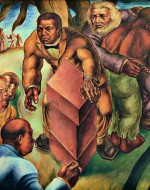

The huge mural by Charles White, “5 great American Negroes” overwhelms us before we even enter the Charles White retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In this first mural Charles White created for the government sponsored WPA mural program, Sojourner Truth leads a march of freed slaves that recedes into the background in a tapering curve on the left. In the center, Booker T. Washington promotes his famous Tuskagee College to potential benefactors standing at a lectern with Frederick Douglass behind him holding a grieving slave. In the right foreground, George Washington Carver peers through a microscope and behind him Marion Anderson performs against a blue sky; the two are linked by a young man reading and a mentor pointing dramatically toward a future.

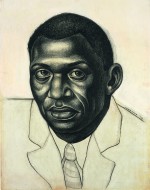

In the mural White has successfully juxtaposed carefully observed portraits of well known African Americans by placing them in a succession of deep and shallow space. Portraiture and powerful black bodies, with a particular emphasis on hands and gestures, characterize much of his work throughout his career. Four other murals during these years, are represented in the exhibition by studies and sketches such as the vivid detailed carbon pencil over charcoal portrait of Paul Robeson. We see Robeson as a powerful but troubled person, a brilliant talent and political activist who payed a heavy penalty for that during the McCarthy era.

The stunning Charles White retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art foregrounds the artist’s deep commitment to presenting the humanity and dignity of African Americans. He died young (1918 – 1979) at age sixty one, and saw profound changes in the US and his own life, but he always followed his own vision

“For me, the thing that matters most is not the form per se, but the depth of the content. I may experiment with new compositional forms, but my chief concern is always with expressing a particular feeling or emotion.”

In his earliest years as an artist in the 1930s, as with many African American artists who became prominent after World War II, the WPA programs provided professional acknowledgement, the support to make art, and a sense of community. African American artists who joined the federal programs were often self educated in art in public libraries and classes, also sponsored by the WPA. The artists in Harlem and Chicago had a community of supportive musicians, poets, writers and visual artists which proved invaluable in their early development.

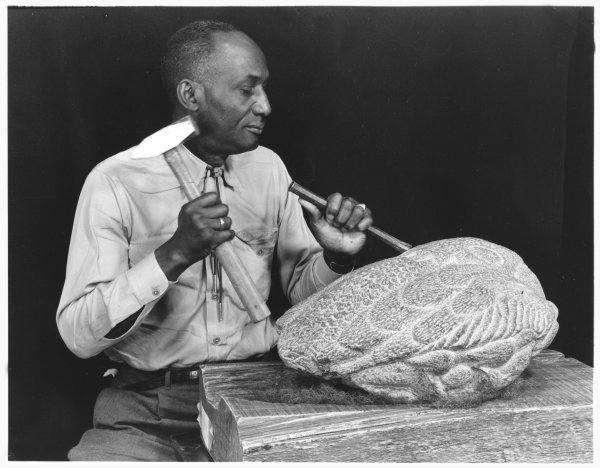

More rural artists especially in the South were isolated before the government programs began, excluded from white public libraries and access to any art training. The community centers and art schools the government sponsored provided both jobs and a sense of personal support. I am thinking here of the less famous, but also extraordinary James W. Washington,Jr. who joined the WPA program in Gloster Mississippi, based entirely on his own study and survival skills in the Jim Crow South. He went on to have a successful career as a sculptor in the Northwest.

As I looked at White’s portraits, as well as his anonymous individual figures, I could feel the challenges that these people overcame, I could feel their anger, and their hopes, their poignancy and power, resilience and resistance, strength and dignity.

White declared “I like to think that my work has a universality to it, I deal with love, hope, courage, freedom, dignity – the full gamut of human spirit. When I work, though, I think of my own people. That’s only natural. However, my philosophy doesn’t exclude any nation or race of people.”

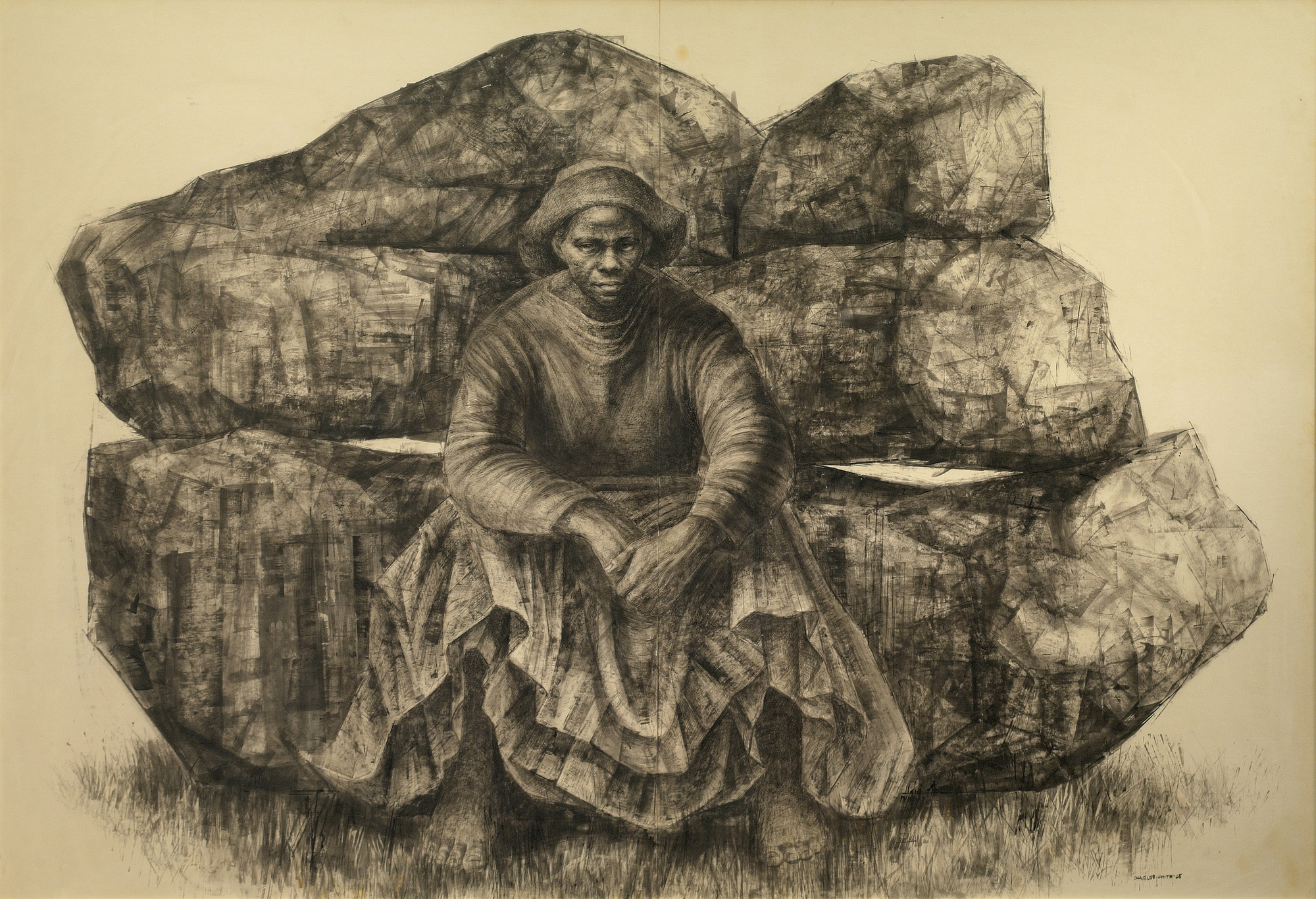

During the 1960s White’s work altered dramatically. His drawings became much larger, dominated by a single figure. General Moses (Harriet Tubman) 1965 sits legs apart, with arms on her knees, hands crossed in front, her expression one of anger. She sits in front of a wall of massive rocks cut unevenly (and brilliantly rendered by White). This work created at the height of the obsession with abstraction in American art, defies us in every way and the large figure defies the world.

In 1966 White created several large figure drawings with the title J’Accuse, based on the anti semitic Emile Zola drama in 19th century France. Each of the five works suggest different emotions. In this drawing we have the enigmatic African mask carried on a woman’s head covered with grass and swathed in a voluminous robe. We see her immense strength in the voluminous robe and determined expression, even as the African sculpture gives her spiritual power that alost seems to lift her up.

White stayed with the figure, increasingly embedding it in a large textured surface. The complex drawing awes us with his mastery. The figures engage the interior lives of people challenged by life. They honor resistance to oppression through strength and love.

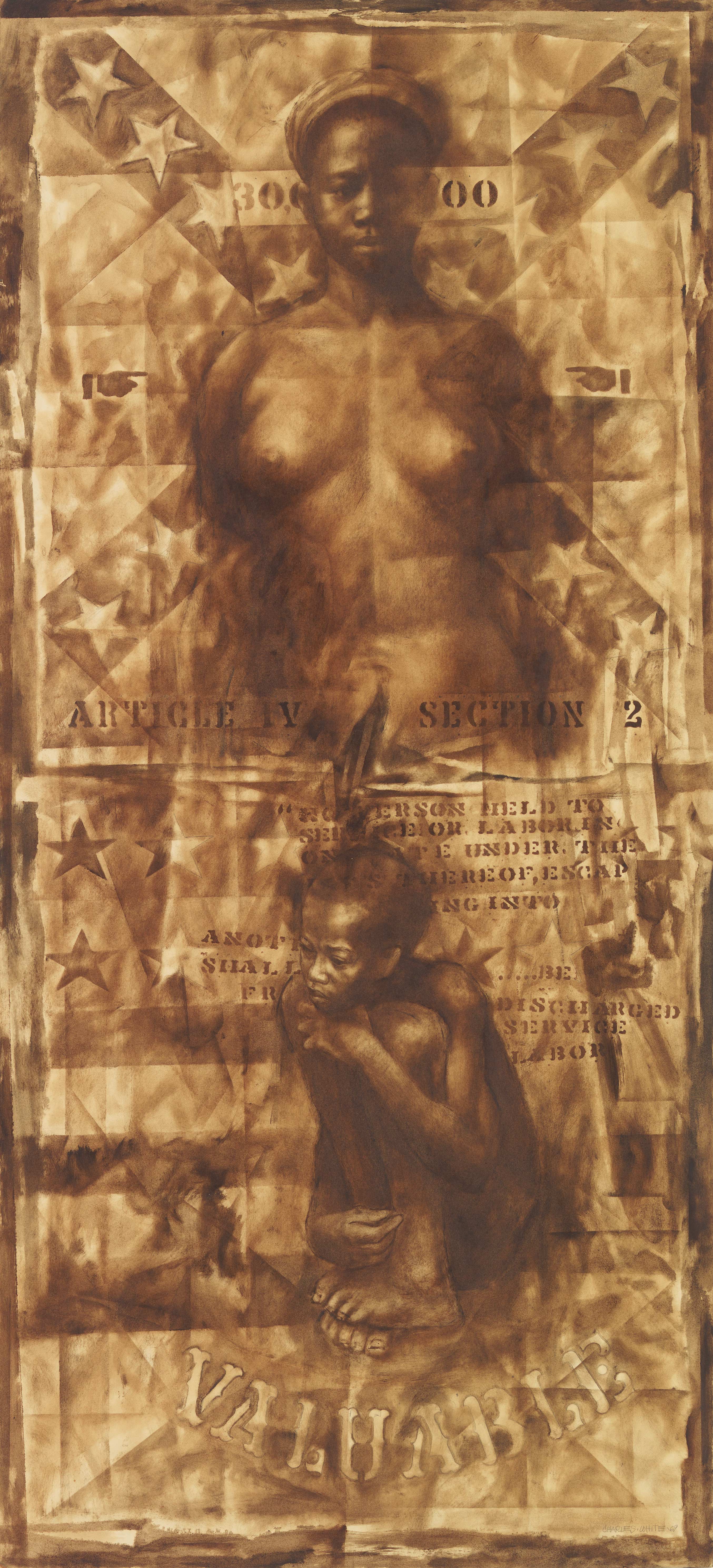

In his series Wanted Posters ( above no 17, 1971) he conveys the injustice of the system through subtle facial expressions and deep compassion.

Just a few years before he died, he was still experimenting with new formats, media and content, as in Sound of Silence, a black man with a large conch shell at his center, suggests symbolism, but ambiguously. Is the shell protecting him? empowering him? We don’t know.

Indeed with Charles White, it is easy to make glib comparisons with white mainstream references, that are often completely inadequate. The most glaring example of this type of comparison is with Our Land, 1951. A powerful and defiant woman holds a pitchfork as she looks out from her doorway. In the catalog she is repeatedly compared to Grant Wood’s American Gothic (which White would have known in the Art Institute of Chicago). She could not be more different from the pale, insipid farmer and his daughter. White’s woman with her giant hands and assertive posture is clearly saying don’t come here or this fork will be a weapon. I immediately thought of the artist Clarissa Sligh’s story of her uncle who was killed and left on her mother’s doorstep when she was ten years old and he was twelve. This pitchfork holding woman protects her family with her working woman’s hands and her very sharp pronged fork.

Kellie Jones’s essay in the catalog “Charles White, Feminist at Midcentury,” provides a much needed new perspective on activist African American feminists in California. We all know that the history of feminism in the art world has been woefully controlled by a group of white women in California. Jones essay gives us a fresh start.

Another great insight from the exhibition is White’s life long close friendship with Harry Belafonte. Indeed, Belafonte narrates parts of the audio in the exhibition. They inspired and encouraged each other. Music played a major role in White’s life and many of his portraits give us famous singers such as Mahalia Jackson and Bessie Smith.

Every one of these paintings and drawings is riveting aesthetically and in its expression of a powerful persevering humanity. We feel these people from the inside, rather than passing over them from the outside because of the color of their skin.

I watched a discussion online between one of the (white) curators of the exhibition, and the (white) director of the Museum of Modern Art. A question from the audience came as to why White was so neglected after he died. In the answer there was no reference to racism in the art world ( nor did that word occur at any point in the discussion). But it is obvious that white art history still practices tokenism when it comes to artists of color. Thank goodness the three museums showing this major exhibition are finally giving one of the great twentieth century artists his due.

This entry was posted on October 29, 2018 and is filed under African American history, American Art, Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, Uncategorized.