Jack Whitten’s Odyssey: A New Perspective

Jack Whitten made his name as an abstract painter in New York City beginning in the 1970’s and had a solo exhibition in 1974 at the Whitney Museum! During the 1960s and 1970s in New York City he was friends with musicians, poets, writers, and other artists. It was a time of mixing media, but he made a name for himself as a painter of large abstract canvases that were purchased by the likes of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

One publication stated at the time of his death

“And as a black artist, he resisted the period’s prevailing impulse of racial representation to explore the plastic and metaphorical possibilities of paint.”

Artsy Editors Jan 23, 2018

I will return to this point at the end of the post.

Other artists honored Whitten with these words:

“Jack would preach that art was one of humanity’s last bastions, and abstraction was where we as black artists could truly be free.” Shinique Smith, artist

“Whitten was always trying to find a celestial dimension in the most prosaic materials.” Massimiliano Gioni, curator

“To talk to Jack was to recognize the beauty and richness of existence, the possibility in even the dimmest times.”

Andrianna Campbell, curator

alll quotes from Artsy Editors Jan 23, 2018

All of these quotes about Jack Whitten as an abstract painter, as well as frequent references to his experimentation with materials give insight into his current exhibition of his sculpture at the Met Breuer .

It is astonishing that they have never before been shown except in small exhibitions in Greece. The sculptures reveal an intricate and layered mind, that brought together the cultures of Africa and Europe on the South coast of Crete, where he lived part time starting in the 1970s. Because I have spent quite a bit of time in Greece, I loved these sculptures. They were stunningly original, lovingly created from various materials, both found detritus and beautifully worked woods, and suggest a calm inner joy that is balanced and exuberant at the same time.

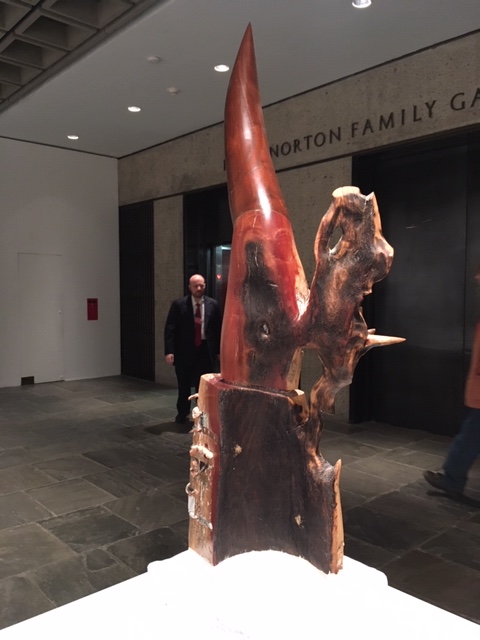

At the entrance to the exhibition (see top of post) stood Lichnos, 2008. The name refers to a “spiny bottom-dwelling fish,” used in “a Greek Fisherman’s stew.” Composed of specific types of wood, carob, black mulberry, the piece is set on a pedestal of whitewashed concrete cinder blocks that immediately made me think of the whitewashing my sister-in-law in Greece does to her house every year. It is the same lime wash used here. What stopped me in my tracks is the huge creative eccentricity of the piece, the juxtaposition of unlike parts to make an assymetrical whole. The stringy character of carob wood makes it hard to carve, echoing the challenge of catching the Lichnos.

There are more references here embodied in the found

materials, to Africa, to Alabama. And as we walk around the work it seems to be a strange beast seeking to escape confinement. The stunning polished red colored carob wood is flame like.

These two installation shots suggest one of Whitten’s inspirations must have been Brancusi (the lower installation is a small show at the Museum of Modern Art). We see the same exploration of materials, of the base, of meticulous aesthetics, of elusive content.

But he is absolutely original, a word I rarely use (nor do I often write about abstract art.) But I strongly felt the layers of content in these works bringing together so many different traditions, mythologies, types of knowledge.

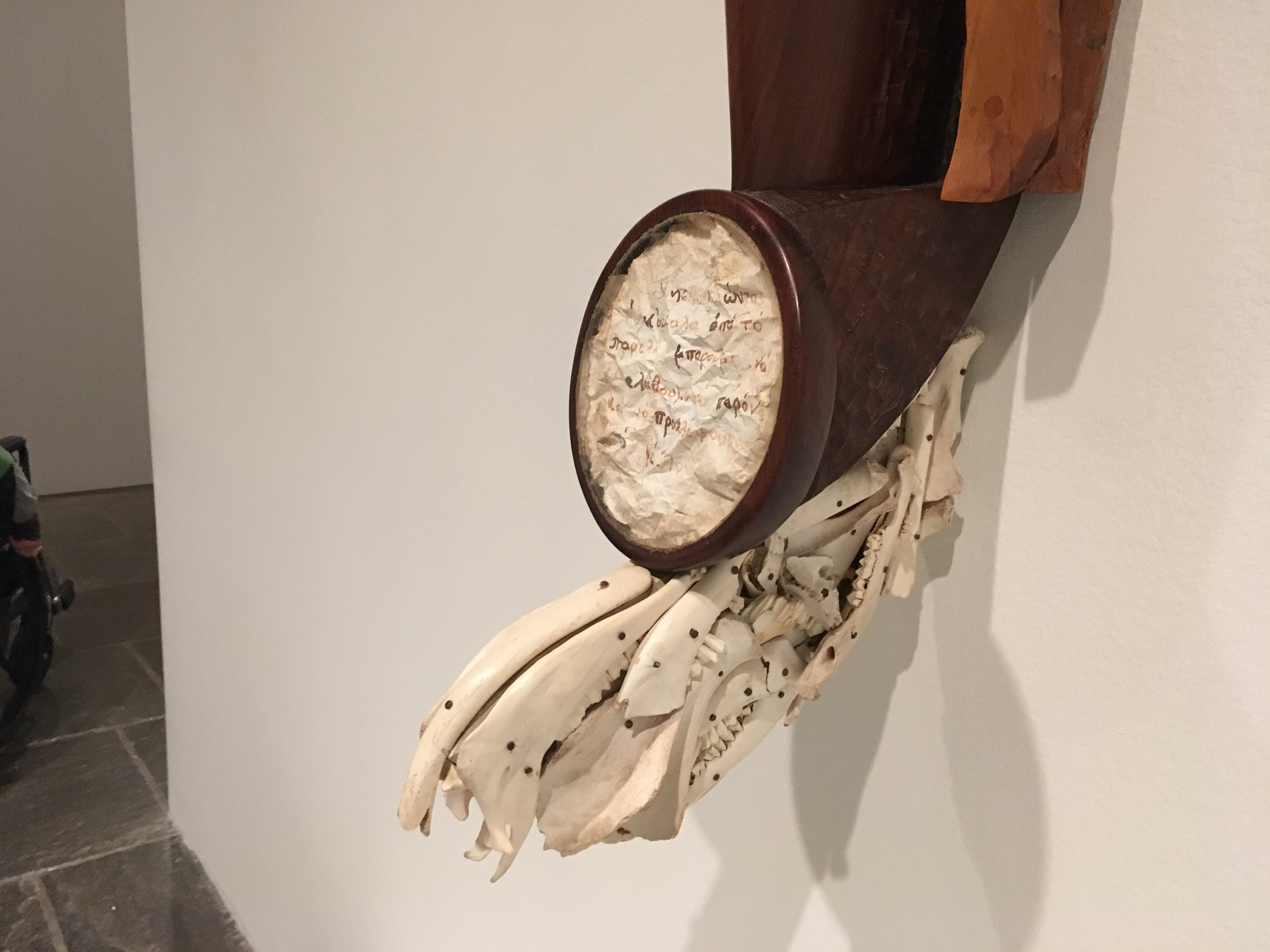

Phoenix for the Youth of Greece, 1983 is one of the earlier sculptures. It includes mulberry wood, olive wood, bone, glass and a small piece of writing. Underneath is an”ossuary”, cluster of bones made of jaws of small fish and above a mysterious parchment with the phrase

“Using the bones from the past, we can understand the present and foresee the future.”

The soft olive wood frames the hard shiny mulberry.

But all of these materials suggest a larger story or myth, illusive, but still very present.

In addition to the layers of mythology in the sculpture, another series of work, the “monolith series” payed homage to great African Americans, in a medium that Whitten developed, hand made acrylic tiles: these stunning works, shimmer in the light, as the “portrait” emerges from its surfaces. But again, they are basically abstract works, with homage to such people as Chuck Berry, James Baldwin, Eduard Glissant, Terry Adkins and Mohammed Ali. The one below is to Chuck Berry. (Black Monolith XI Six Kinky Strings: For Chuck Berry)

The riveting complexity of the surface evokes music, and certainly that is another crucial reference point for Whitten.

It is exciting to be confronted with a body of work by a well known artist that has never been shown before. All of these works are a revelation. Here is the Tomb of Socrates.

with wild cypress, black mulberry, marble, brass and mixed media

It is shaped like a shield, with all sorts of found materials . At the center is a black stone that suggests the philosophers skull. As we know Socrates died by drinking poison because a new political order ganged up on him and declared him dangerous. We need this piece today to remind us of what happens when governments reject knowledge.

Why have these sculptures never been shown before? I came up with the idea of logistics. They were all made in Greece, they are fragile, they are embedded in that landscape, that history, mythology, that geography, not far from Africa. Perhaps Whitten felt he wanted them to stay there, whereas his abstract paintings are very much a part of US American post World War II world.

He was one of a handful of African American artists to succeed throughout his life in the mainstream. Was he simply better than those who have less recognition, or was he less threatening because he did not pursue political content. Thinking about the tone of approval in the quote at the beginning of the article, abstraction was certainly more illusive as a means of speaking than the unavoidable imagery of a Charles White ( who was also successful, but in a different arena) .

But I will say that for Whitten it was not only what was in style, it was definitely not because he wanted to hide behind it in order to be safe. Abstraction worked with his abstract way of understanding the world. His abstraction is not an empty gesture, it is an act based on wide ranging exploration of ideas.

Based on the homages quoted above , it is clear that he was held in a certain amount of awe by his colleagues and fellow artists. I wish I had known him. Perhaps I would know the answer to my question.

There is no doubt though that he was deep, poetic, and incredibly willing to take chances. He came from deep poverty in Alabama in the 1940s. His father died when he was five, his mother left with seven children to raise alone. She must have been a remarkable woman. He went to segregated schools but was already interested in shop and music. But what a leap to end up as a major painter in New York City already in the early 1960s.

So the mystery of life and success remains, is it initiative, luck, mentoring, perseverance, charm, talent. We know that for a black man in the art world of the 1960s and 1970s in New York City, brains alone was not enough. The fact that his experiment with materials fit with what was acceptable at that time is a conjunction of time, place, person, inclination. He may also have been just lucky in his timing.

Late 60s and early 70s the art world was shifting from its exclusive focus on white men making abstract paintings, but diversity was not yet established as a crucial consideration ( it still isn’t). He slipped in then, and off he went.

But to return to the sculptures, which I can’t help feeling are his greatest art. Why were they never shown? Because they didn’t “fit” what the art world wanted? Or because he saw them as personal and informal explorations. I want to believe that he saw them as an ongoing exploration, a synthesis of all his ideas. They were not ready for the world until after he died.

Thank goodness we have them now.

This entry was posted on November 3, 2018 and is filed under African American fiction, African American history, Uncategorized.