South African superstar photographer Zanele Muholi at the Seattle Art Museum

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

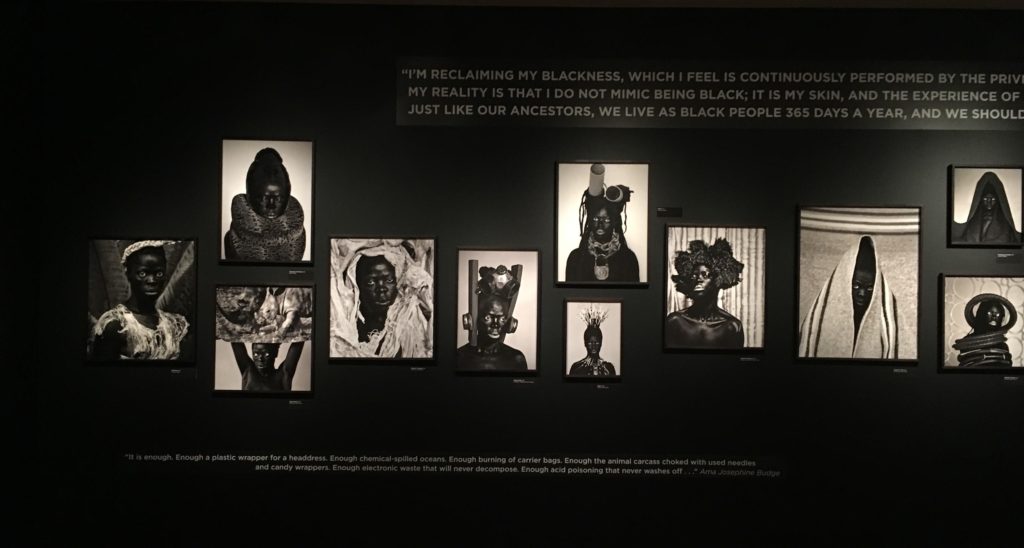

Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness

South African superstar artist Zanele Muholi bursts out of the Jacob Lawrence and Gwen Knight corner gallery at the Seattle Art Museum: “I’m reclaiming my blackness.” Their exhibition “Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness,” spills into four adjoining spaces.

First, we see the huge signature self-portrait visible from several galleries away, invading our experience of the work of mild white men in adjacent galleries. The artist wears a headdress of sheepskin that takes a lion’s mane to the next level of luxuriance. Keeping in mind that it is the male lion that has a mane, this lioness identifies as they. They look to the side, focusing beyond us.

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape

Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

Turning around, we see the artist posing in a mural scaled photograph in what evokes a classical reclining nude posture, until we realize that it contradicts that tradition of exploitation. Lying on their side and holding tightly to multiple plastic pillows that cover all specifically sexual body parts, they displace and occupy the reclining nude tradition constructed for male eyes throughout art history.

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape

Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

Moving into the next space, another 4-foot self-portrait evokes the statue of liberty, with the crown replaced by large coils of black foam and the gaze directed skyward. Again, the icon is redefined, reoccupied, remythologized. As “liberty” has become an empty word, this upward gaze expresses that impatience and absurdity.

The oblique gazes accent the whites of the eyes in every image in the show. As we enter the main gallery, painted entirely in black on two walls, we experience these intense looks over and over, trapped as though by pincers on four walls of self-portraits. In each work the artist transforms into a goddess, a miner, a queen, a king, and even a rocky cliff or forest. The artist collects found materials from various places: buying from stores, clothing from friends, items found in hotels or friends houses. The props enable layers of metaphors and political references that range from historical to contemporary, from personal to public

.

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

For example, in a self-portrait with South African money pinned to their head, a cow’s skin pinned on their shoulders, the references can be to the “bride price,” the selling of woman like cattle, but defiance and resistance embodies the posture and the gaze, even as it seems to suggest surrender.

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape

Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

In another work, an homage to her sister, a gentle and proud Muholi wears a crown and necklace of rubber inner tubes that confer majesty, and a defiant inversion of the violent history of rubber in Africa, where the Belgian King Leopold ruthlessly killed thousands to satisfy his thirst for that “natural” product. We can draw a straight line to the exploitation in the Congo today to obtain the minerals for our electronic gadget

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape

Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

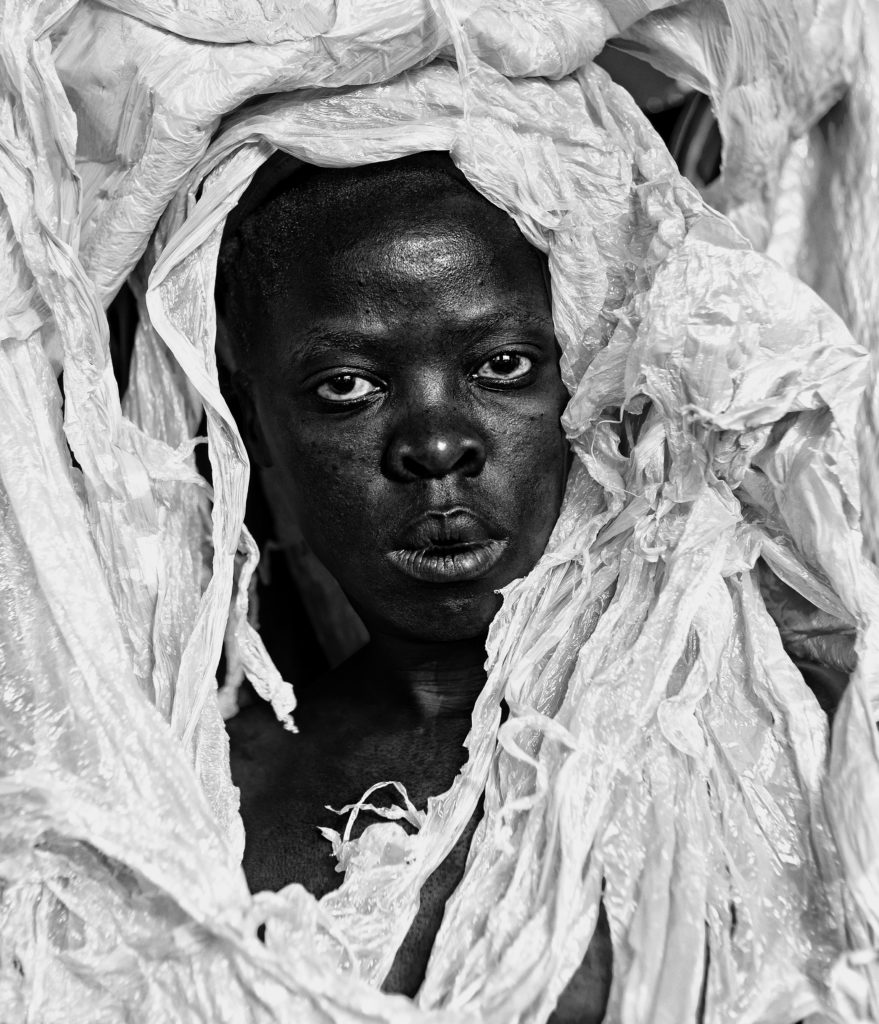

Every single image can be approached with layers of meanings, as brought out by the intense and indispensable series of essays in the catalog. About the portrait “Kwanele, Parktown 2016 it is enough,” a face surrounded by plastic detritus, Ama Josephine Budge writes:

“Enough a plastic wrapper for a headdress. Enough chemical spilled oceans. Enough burning of carrier bags. Enough the animal carcass choked with used needles and candy wrappers. Enough electronic waste that will never decompose. Enough acid poisoning that never washes off. Enough villages under sand. Enough sand stolen for cement. Enough salinized cropland. Enough desertification. Enough brown bodies on the shoreline. Enough plastic wrappers forced migration. Enough polyethylene saran-wrapped suitcases—everything I could grab in a moment—abandoned at the immigration centre. Enough tear gas in the eyes of protestors. Enough extinct species. Enough plastic-strewn beaches. Enough. Enough. Enough. Enough. Enough. How many times must I say, ‘kwanele’ it’s enough, before what you hear is not more but too much.”

The directness of the artist’s bold head shots controls us as we look back seeing the steely gaze, the power, the anger, the courage. Muholi speaks of occupying public space, the spaces given to white people. As a South African, Muholi is particularly aware of the segregation of public space and its history in apartheid, but the entire planet is rapidly becoming an apartheid state with migrants imprisoned at militarized borders or drowned at sea.

Prior to this series, Muholi in an ongoing series photographs the LGBTQIA people of South Africa in a series with the title Face and Phases . They are honoring those murdered and those living amid murders and crimes against their community. Their own studio was ransacked, and unprinted work deliberately destroyed.

Turning the camera back on their own face in these portraits, Muholi allows no objectification of the other, deliberately negating a long tradition of the black body in ethnography, anthropology, tourist and so called “documentary” photography. The body is Muholi’s, the narrative is Muholi’s.

The statement is both local and global: the artist has constructed the images all over the world and identified each image by city, and in isiZulu, their native tongue. Working in black and white (albeit with color film) is another political reference to photography as created by white eyes and cameras calibrated in F stops for white skins. Here the subtle tones of black emphasize the many nuances of dark skin colors.

We are caught in the web of these layered metaphors that defy the state of our present world with brilliant defiance. “Hail the Dark Lioness”! (until November 8).

Don’t miss the videos behind the “Lioness” and read the articulate catalog!

This entry was posted on September 23, 2019 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Feminism, Uncategorized.