“Climate Change Alert through Arctic Aesthetics” by Jean Bundy, Art Critic based in Anchorage Alaska

This paper was presented in the International Art Critics Association session at the College Art Association February 2020 Jean Bundy is the Climate Change Envoy for AICA-INTERNATIONAL

Introduction

In the Eighteenth Century Captain Cook era, when exploration and desired acquisition of the Pacific Northwest was mapped and illustrated, it became evident that these locations had abundant flora, fauna, and minerals. Encountering the Indigenous, who were often abused, was a resource for survival, scientific research, and financial gain, which continued through the Russian takeover, the Alaska purchase, 1867 and yes, through Statehood, 1959.

In the Twenty-First Century, Alaska Natives and other Arctic aboriginals are finally being appreciated for stewardship of their lands and acute awareness of Bush Climate Change. Explorers/scientists and tourists venture to the 49th state, not to claim territory, but to paint, photograph, wilderness adventure, and observe/document the Arctic with cameras/instrumentation unimaginable to Cook.

Alaska’s changing environment has been obvious to all residents for the past several decades. Increased forest fires, die-offs of: Salmon, Murres, and Seals, bug infested trees, and toxic algae, are evident in urban areas as well.

Lack of snow and melting glaciers impact Bush living as seacoast towns are eroding, and icepacks needed for safely hunting sea mammals are shrinking. Increasing amounts of CO2 found in the ocean are also leaching out of the ground as tundra melts, witnessed by rising/falling Pingos.

These are humongous problems that can’t be solved without cooperation from governments willing to shell out large sums of cash while putting their countries on energy diets and adopting more user-friendly recycling and pollution programs.

So, does educating the public to the rapidly melting Arctic through aesthetic visualization do any good? And are there ironic silver linings found within Global Warming such as: longer growing seasons, anthropological discoveries, Arctic communities benefitting from installation of fiber-optic cables because of the surfacing Northwest Passage?

The Christies’ Symposium, June 11, 2019, stressed that “art brings the invisible to our attention.” So why not use this phenomenon to extend Heidegger’s definition of ‘Being’ by cleaning up the living Earth?

Aesthetic narratives, that steamroll Captain Cook’s or Averill Harriman’s masculine adventuresome fantasies, get replaced by gender-neutral themes: oceanic pollution, sea ice melt, coastal erosion, and respect for Indigenous populations.

Six artists working across the Arctic possess different backgrounds which culminate in multiple perspectives, making art to heighten awareness of Climate Change, thus heralding the aesthetic importance of the North.

1: Ásthildur Jónsdóttir (Iceland) ‘Arctic Aesthetics, 2019’

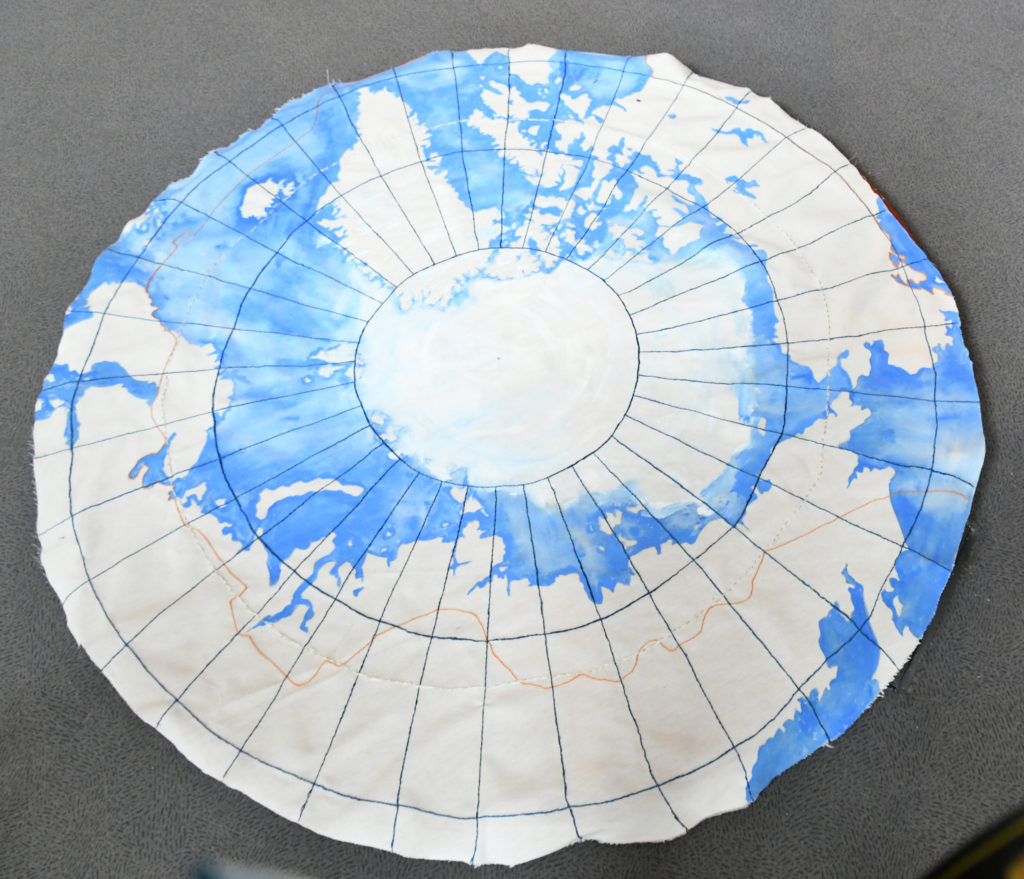

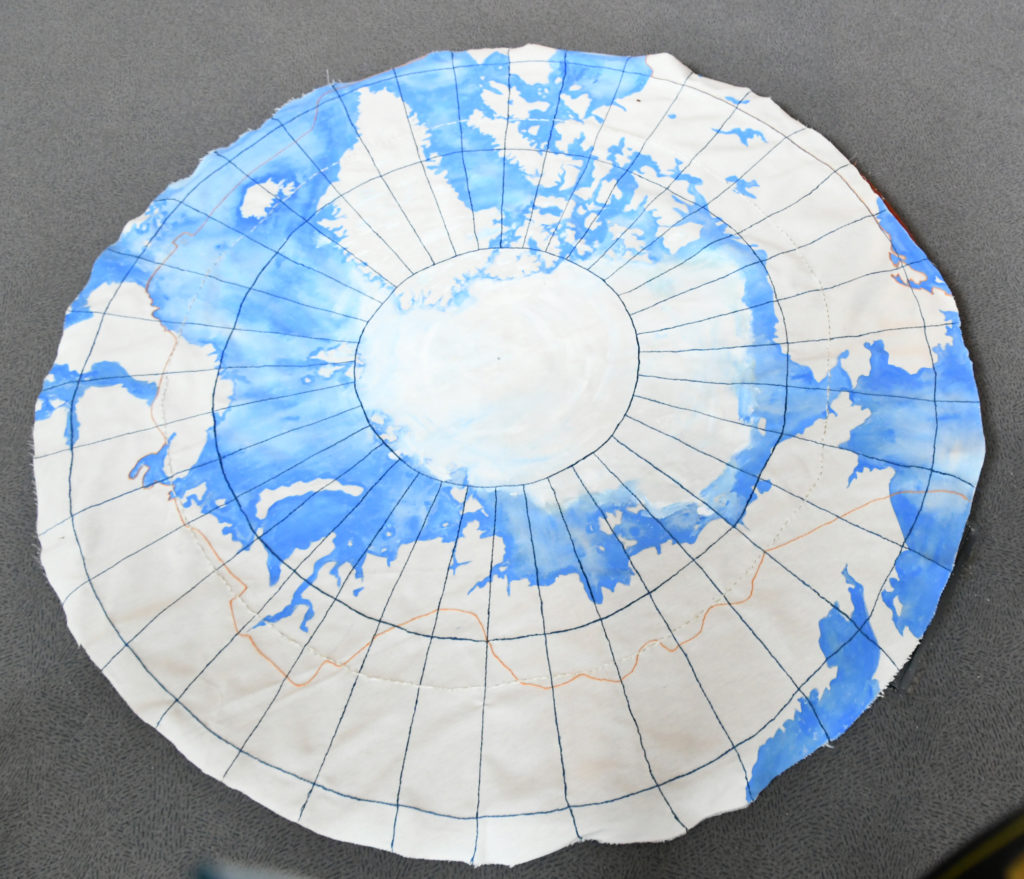

Jónsdóttir hand stitched/painted the Eight countries that reside in the Arctic Circle, saying she wanted to be “involved with issues concerning the ecology of the planet….[and to encourage engagement] in the beauty of the Arctic, both physically and psychologically.” Her art moves beyond craft morphing into fine art, overlaying the essence of ancient artifacts upon contemporary art making. Jónsdóttir’s piece was displayed at the Second Arctic Arts Conference, Rovaniemi, Finland, June 2019, while a similar photographic map was projected at the First Arctic Art conference, Harstad Norway June 2017.

Most maps are shown from the vantage point of the equator where notable historic travel, transportation and colonial entrepreneurship occurred. Looking at the world from the top down, disorients, but ultimately creates a greater sensitivity about this region and its importance to the rest of the Globe, in light of accelerated melting.

Referencing Alaska, beginning with Russian colonization, and continuing under US ownership, white Settlers came and established towns and businesses without recognizing the historical rights of Indigenous populations. The Alaska Natives Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) 1971 resolved aboriginal land rights by transferring 40 million acres of land to about 200 corporations in which Alaska Natives are shareholders. Because the corporations are businesses and not governments, ongoing disputes between Native villages and the Federal/State agencies continue.

Scandinavia’s history, like Alaska’s, is about white Settlers/entrepreneurs disrupting the semi-nomadic Sámi ancient traditions. Like Alaska Natives, Sámi view land as a borrowed gift/resource for hunting and fishing and don’t conceive of land as Western ownership/real estate. In the late Nineteenth Century, the Norwegian government began appropriating Sámi lands which were resource rich and economically viable. Sámi were ordered to assimilate into Norwegian culture and language; children were sent to state run boarding schools like Alaska Native children.

In 1987, the Norwegian government gave Sámi their own parliament, with other Scandinavian Sámi parliaments also established. But many feel this attempt to re-establish/recognize Sámi governance is window dressing. For example, governments cull Sámi reindeer herds, rationalizing there are too many per acre. In reality, grazing lands are more remunerative developed for natural resources.

It has always been perceived that the North can’t think for itself. There is the “North” created by outsiders, which often overtakes insider “North.” The intent of recent Arctic Arts Summits is to visualize cultural similarities between Arctic countries which are experiencing similar political and environmental frustrations.

However, attitudes are changing as Indigenous groups are becoming appreciated for their acute understanding of Nature’s harmonies/balances, as they strive to be guardians of all things land/sea related. The outside world still has the stronger hold on mineral rights as well as control of hunting and fishing. However, Tourism has become a new resource for Arctic prosperity, with Indigenous art the preferred commodity sold.

Sadly, fake Sámi and Alaska Native art is also popular. Many residing in the North feel there are too many tourists, too many cruise ships, polluting/eroding natural surroundings.

Finding an Arctic voice, which appreciates the beauty of landscape/wildlife, while coping with Twenty-First century development, continues to challenge ancient Indigenous ways, and now the impact of Global Warming. Can there ever be a balance between development and the environment? Exhibiting aesthetic objectivity helps imagine solutions.

2: Brian Adams (Iñupiaq) photographer, ‘Kivalina Sea Wall, 2007’

Adams’ photograph seeks humanity beneath the surface. Kivalina is an island of four hundred Iñupiaq residents in the Northwest Arctic Borough, which is slowly returning to the sea. Residents hunt the Bowhead whale, which becomes harder as ice packs grow thinner. Before missionaries were sent to Alaska and imposed Western ideas of stationary communities upon Natives, seasonal relocation to inland fish camps was the norm.

Disruption becomes a much bigger deal when towns with buildings, bureaucracies, and communication systems are permanent places. Boxes and sandbags are a temporary fix to the reality that endangered villages will eventually have to move and at great expense.

3: Marek Ranis (Poland/USA), associate professor at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte ‘Faith, 2017’

Ranis’ Faith (2017), a transparent digital print of an inverted oil rig superimposed against an Arctic sunrise/sunset, situated in a window, mimics stained glass, suggesting sacred venues of contemplation and rejuvenation. Ranis positions this handsome machine, center stage, like the image of a saint in a cathedral window. This upside down rig allows viewers to pause and contemplate mechanisms that extract needed oil, providing Norway with wealth and social services, but also the possibility of an environmental disaster.

However, the gorgeous landscape behind the rig, produced by the sun’s energy, can also generate devastation without man’s assistance. The sunrise/sunset becomes a metaphor for considering frictions between increased mineral exploration, and Sámi reindeer herders lobbying to preserve needed pasture lands. The Arctic tug between preserving raw beauty and harnessing nature for profit continues throughout all communities.

In Alaska the debate about whether to allow copper mining near Bristol Bay, home to commercial and recreational Salmon fishing, continues with the conundrum that providing jobs to Indigenous locals, who can’t rely on total subsistence, may pose environmental consequences if a mine were to leach toxins. Harkening back to early Twentieth Century ‘Heideggerian’ discussions on the potency of the machine age, then fast forward to the Twenty-First century with its sophisticated automation, has progress been made when it comes to utilizing technology safely/efficiently and at what expense to the environment?

4: Geir Tore Holm (Norwegian), ‘Fughetta, 2014’

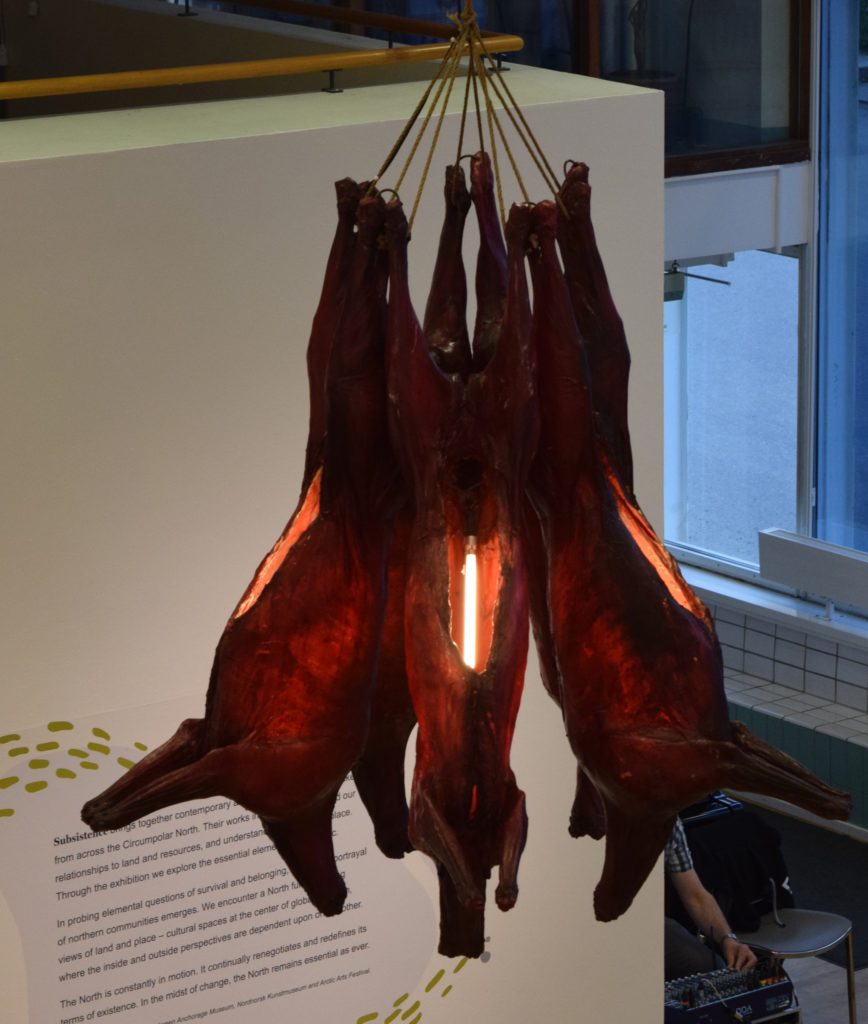

Holm’s Fughetta (2014), are reindeer carcasses soaked in resin and electrified, resembling The Human Body Exhibition. Holm, who lives on a farm, is reconfiguring reindeer, the livelihood and sustenance of the Sámi, as a surreal chandelier or butchered meat hanging/aging in a cooler. By isolating reindeer from grazing sites, viewers are forced to think about Nature that can quickly be refigured into a heartless commodity.

Is it proper for the Norwegian government to cull Sámi herds, so the real estate can be developed? Perhaps further Climate Change will make what seems unnatural, the taken-for-granted norm. Fughetta is also reminiscent of compositional Fugues which have multiple voices. Fughetta suggests musical rhythms, as the reindeer remains swing from a ceiling. Pendulum motions suggest hangings too, and the tug of war between environmental groups and mining companies.

5: Allison Akootchook Warden (Iñupiaq) and Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit) video, ‘Envoy, 2016’

Warden, known for choreographed rap, and Sitka filmmaker Galanin, produced the video Envoy (2016). One segment shows a Polar Bear frantically pacing in a not so politically correct ‘Natural History’ concrete space. Until recently, zoos kept animals confined as specimens, giving little thought to their environmental needs.

The Polar Bear has become the poster child for Global Warming as Arctic sea ice, the bear’s habitat, is melting. Ironically, zoos may be the only places Polar Bears will exist, hopefully better than the one pictured.

In Warden’s footage the matted bear who resides alone in a concrete jungle represents environmental carelessness at its worst, as well as man’s lack of foresight. Although, not the cuddly creatures appearing in Disney footage, or Coke commercials, Polar Bears deserve saving.

James Temte (Northern Cheyenne) adjunct professor at Alaska Pacific University, ‘THINK NEXT OVER NOW, 2019’

6: James Temte (Northern Cheyenne) adjunct professor at Alaska Pacific University, ‘THINK NEXT OVER NOW, 2019’

Temte’s outdoor billboard-esque photograph is made of large plastic tessellations, picturing a pre-teen standing in a field, clasping a handful of dirt/vegetation. The youth could be male or female of any ethnicity. This young person is wearing a logoed t-shirt and warm-up jacket that is also gender-less. Hair is shoulder length with bangs—any kid’s cut.

Some of the background squares have deliberately been omitted, creating black emptiness, suggesting what life might be like when Climate Change erases the Earth, as we know it. Since this is a parking area, ‘handicap’ signs not only couldn’t be removed, they become part of the composition. One of the ‘handicap’ signs fetched up on the breast pocket of the youth’s track suit and looks like the garment came with that label.

This entire piece becomes a narrative for Global Warming, with the ‘every-youth’ cradling a piece of Earth. Yes, we are ‘handicapped’ as we begin to figure out how to balance productivity with cleansing the environment. Each word of ‘THINK NEXT OVER NOW,’ executed in different fonts, makes a statement, becoming contemplative verbiage hanging over the youth, landscape, and all of us.

Driving by Temte’s mural forces Anchorage residents, who are going about their daily routines, to consider Climate Change—subtleties override being scolded. Global Warming has been happening/accelerating/ignored since the Industrial Revolution and can’t be fixed ASAP, which really depresses teens like the one depicted in this mural.

Of note: mysterious dust was found in late Nineteen Century Greenland, by Swedish explorer Erik Nordenskiöld, finally identified as coal, blown North from the Industrial Revolution of Europe and North America (Hatfield 174,175).

According to Temte, “I see a need for including art specifically public art in the climate change conversation. As a scientist I know that data collection is important to track the impacts occurring in the arctic however, looking at an excel spreadsheet of data points may not be as compelling as seeing our stories depicted in murals across our communities. The language of art can connect with everyone from children to our elders. The more that communities can come together and agree that actions need to be taken and that we are all a part of the solution the more ground we can make on addressing and potentially slowing the effects of climate change.” Like all things social and political, change doesn’t occur until a panic button is visualized, and hopefully pushed.

Conclusion

At Christie’sSeminar, New York City, June 11, 2019, it was agreed that Global Warming was complicated and shouting at people to reduce Carbon Footprints fails.

According to a wall label at the Arktikum Museum, Rovaniemi, Finland, “The world is becoming increasingly connected, through shared social, environmental, cultural and economic challenges, requiring different forms of transnational knowledge and solutions.”

Last April’s Notre Dame fire proved art is the greatest metaphor for Globalism. On Place Jean Paul II, a plethora of ethnicities stood, prayed and cried, while millions worldwide watched on electronic media, as fire fighters saved most of the structure. Instantly monies poured in from all parts of the Globe, because people worldwide want to feel a part of rebuilding a monument which has endured the historical dichotomy: suffering and euphoria. Fire didn’t care about cultural divides; it just enjoyed melting lead and smoldering centuries old wood into charcoal.

Art promotes the invisible through visual dialogue, museum or neighborhood involvement, and self-awareness of belonging to place. Artists with a sincere investment in the Earth are not only stewards, but beacons for the mess that needs cleaning-up.

Photographs by David Bundy except Brian Adams (Iñupiaq) photographer, ‘Kivalina Sea Wall,

Bibliography Most information was gleaned from reportage at the First Arctic Arts Conference, Harstad, Norway, June, 2017 and the Second Arctic Arts Conference Rovaniemi, Finland, June, 2019, which became online articles (www.anchoragepress.com) and an AICA-International 51st Congress, Taiwan, Fall 2018, presentation.

Papers by Jean Bundy

Arctic Environmental Challenges Through Virtuality, is available through AICA-INT (AICA Taiwan Congress, November 14-21 2018)

ART SLEUTH: Norway’s Arctic Arts Summit (July 4, 2017)

ART SLEUTH: Norway’s Arctic Arts Summit — part 2 (July 11, 2017)

The Sleuth Takes Arctic Art to Taiwan –Part 1 (December 5, 2018)

Alaska Native Artists Help ‘Make the North Great Again (June 24, 2019)

James Temte’s Outdoor Mural — It’s Not Outsider Art (November 4, 2019)

Temte, James. “Re: Jean Bundy for the Anchorage Press.” Message to the author. October 30, 2019. E-mail

Books: Quoted or Consulted

Fringe, edited by Maria Huhmarniemi, ISBN: 978-052-337-156-9; Pdf ISBN: 978-952-337-157-6

What is the Imagined North? Daniel Chartier, Arctic Arts Summit, 2018, ISBN: 978-2-923385-25-9

Arctic Pocket Book,Artikum Service Ltd.2017, Finland, ISBN: 978-952-938576-8

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time,translated by Joan Stambaugh. State University of New York Press, Albany, 2010

——The Question Concerning Technology, translated by William Lovitt.Harper and Row, New York, 1977

McAleer, John and Nigel Rigby.Captain Cook and the Pacific.Yale University Press, New Haven, 2017

Jamail, Dahr. The End of Ice.The New Press, New York, 2019

Hatfield, Philip. Lines in the Ice. Philip Hatfield, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 2016

Adams, Brian. I AM ALASKAN.University of Alaska Press, Fairbanks, 2013

This entry was posted on March 19, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.