The New Deal Era and Today: Some comparisons

Recently references to the New Deal programs that provided federal assistance to painters, photographers ( Dorothea Lange being the most famous), and theater ( the shut down of Hallie Flanigan’s radical Theater Program), abound in our press these days, as the Corona Virus devastates the arts and the creative sphere. Even the conservative commentator David Brooks was suggesting a federal service work program for youth starting in the fall.

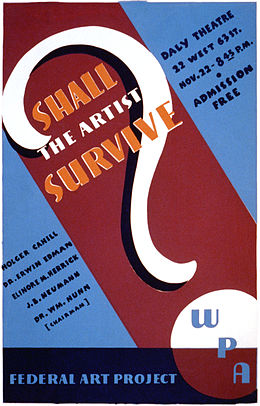

Today May 7 is the day that Roosevelt launched the Works Progress Administration. The Art Programs actually began much earlier, immediately after his inauguration in 1933. The government began to develop a program with an hourly wage to ensure the survival of artists. They followed on several years of fragmented private programs that helped the artists: one early program was organized by the College Art Association.

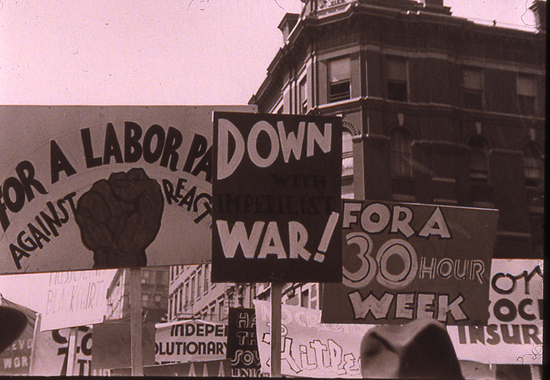

But these govenrment programs did not happen spontaneously. Government support was the result of the artists forceful demonstrations and their self proclaimed identity as unemployed workers, affiliated with powerful unions. Artists’s confrontational tactics led the government to see them as a force to be contained. Since artists identified with workers, the government could justify supporting them as workers.

Harry Hopkins was a social worker whom Roosevelt hired to direct the entire WPA program. He believed in art programs.

In my book Art and Politics in the 1930s, Modernism, Marxism, Americanism, I discuss the political positions of the cultural environment in those days , as suggested in the title. As today, there were great disagreements between the left and the right. There were pro Nazi rallies, refusal of boats filled with desperate Jewish refugees, and fear of Soviet policies on the one hand, and Communists and Socialists on the other hand. Translated into today’s terms, we have White Supremacists and some deeply right wing Republicans on the one hand, and Bernie Sanders followers and believers in socialist principles on the other.

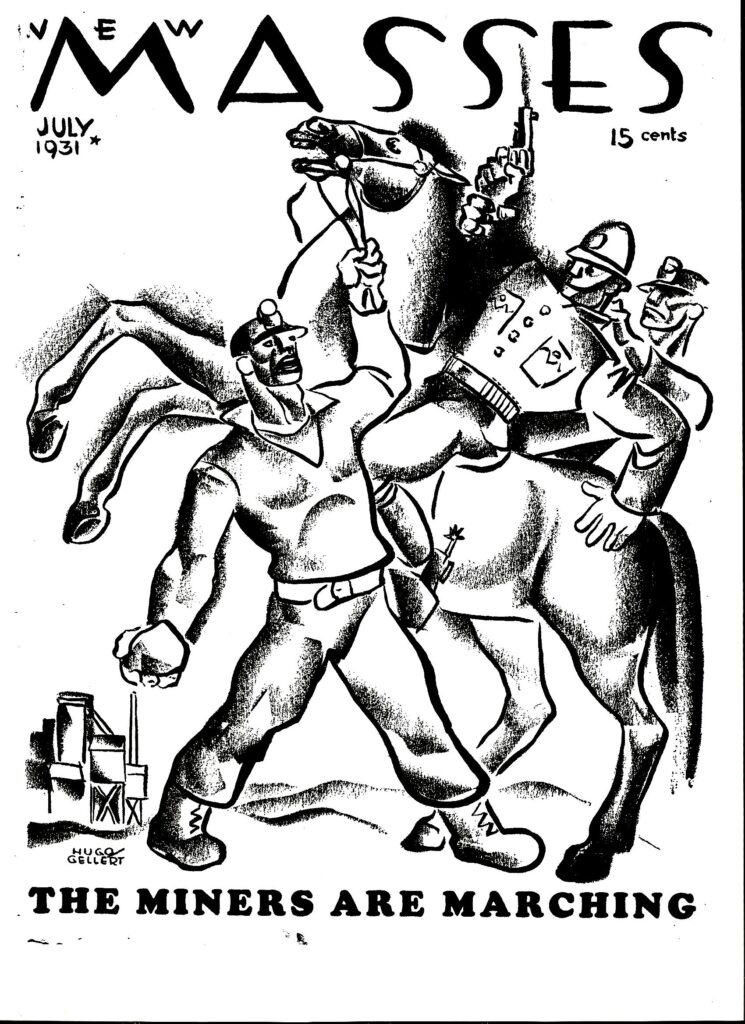

Official Communism as in joining the party was not widespread among artists, because they didn’t like to be told what to do, but some artists did become deeply involved as seen in the radical left newspaper New Masses.

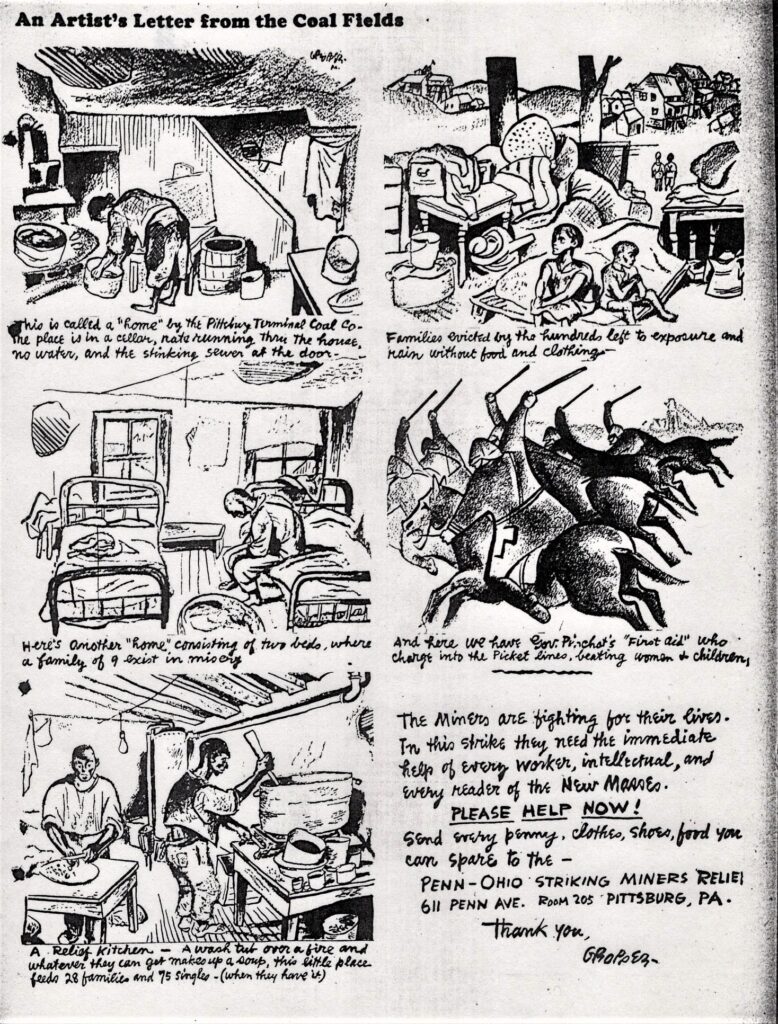

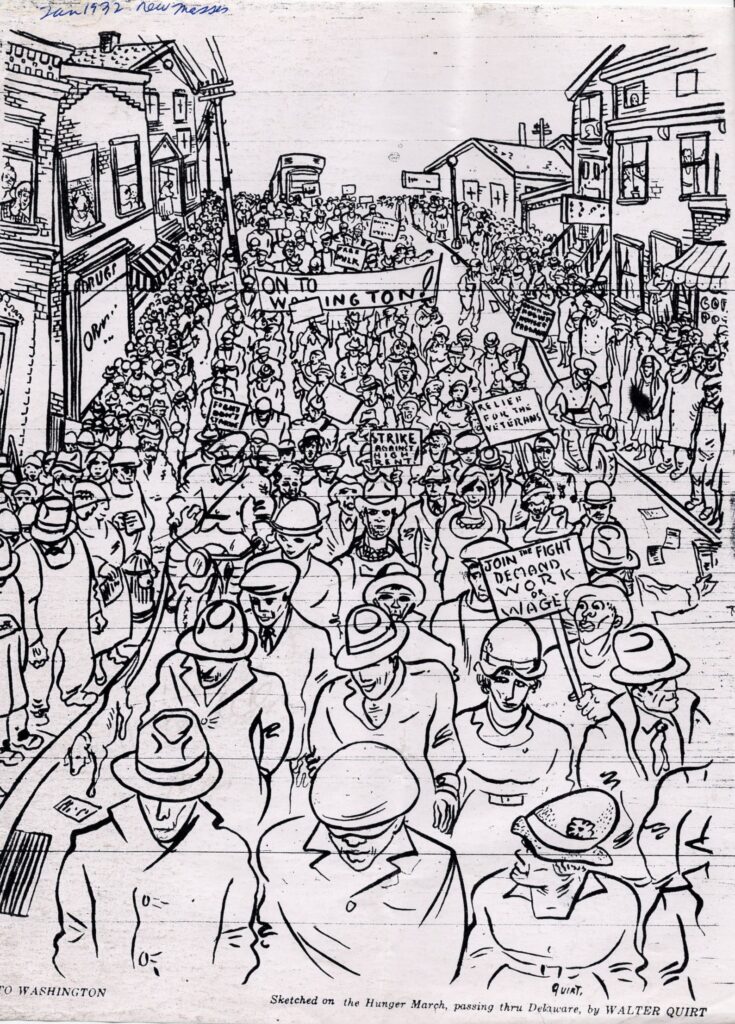

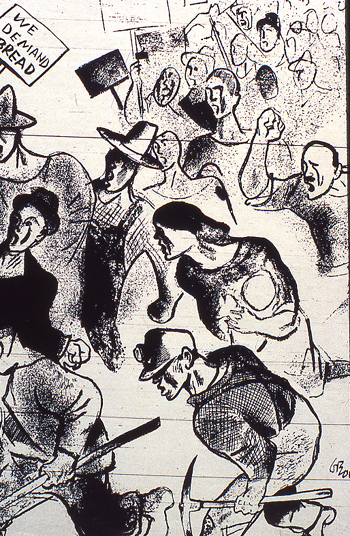

With widespread unemployment, artists and writers joined forces with striking workers. They believed in collective action, in supporting those who were suffering.

Wiliam Gropper depicted the miners living conditions and their conflicts, .

He and Walter Quirt, among others, participated and recorded the World War I veterans asking for food as they marched to Washington in 1932.

Other artists went through the South and photographed victims of the Dust Bowl ( Ben and Bernarda Shahn were the earliest to drive into the South) and of course Dorothea Lange’s famous photo is in this category although with different sponsorship, the Farm Security Administration.

Paul Strand made films that explained why there was a Dust Bowl, such as The Plow that Broke the Plain.

Radical writers, theater producers, actors, and even musicans all joined in the cause of protesting injustice.

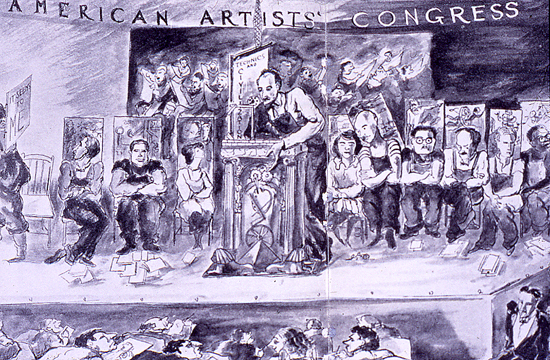

They banded together in the Artists Union and the Popular Front as well as the American Artists’ Congress, which brought together a wide political spectrum of artists and writers. Left to right above: Heywood Broun (radical journalist), George Biddle, Stuart Davis, Julia Codesido ( from Peru), Lewis Mumford ( at podium), Margaret Bourke-White, Rockwell Kent, Jose Clemente Orozco, paul Manshi, Peter Blume, Aaron Douglas.

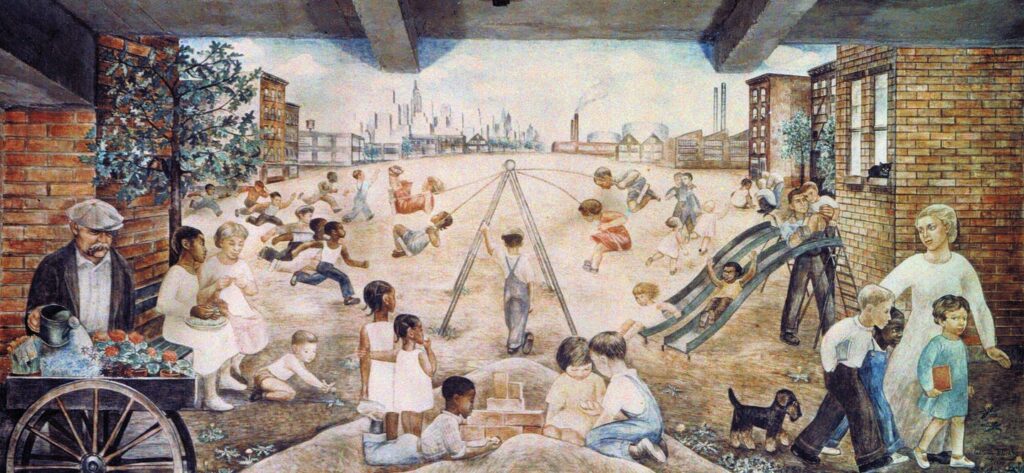

That first federal program was called the Public Works of Art Project. It was the first art program to directly utilize one million in relief funds out of 400 million allocated for relief for workers. through the Treasury Department. Edward Bruce was the tireless planner : Here is one official description: “During its short 5-month life in 1933-34, the PWAP employed 3,749 artists, who created 15,663 works of art. These works included 7 Navajo blankets, 9 bas reliefs, 42 frescoes, 99 carvings, 314 drawings, 647 sculptures, 1,076 etchings, and 3,821 oil paintings. Such works of art decorated public schools, orphanages, public libraries, and “practically every type of public building.” Museums sought and displayed the work, and many Americans were “made familiar for the first time with the contemporary art of their own country…”

A little over $1.3 million was spent on the project (about $23 million in 2015 dollars), with nearly $1.2 million going towards the artists’ paychecks”

But this program failed to reach many people. It stumbled on the idea of “quality.” The advisory committee was drawn from museum directors, all men with one exception, Juliana Force of the Whitney Museum. It only funded established artists.

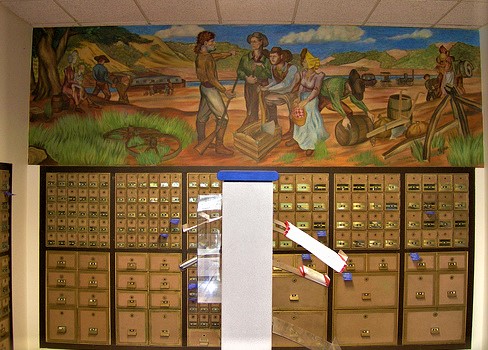

Edward Bruce went on to lead the Treasury Section of Fine Arts which created murals for Post Offices and Federal buildings. At the end of the decade he sponsored the 48 states competition . But as everyone knows, these were not exactly radical. They were tied to the “American Scene”

Often artists sent out to rural areas had to negotiate with the people on what to represent or fatten up their farmers!

A new relief program began in the summer of 1935: Federal Project Number One, included theater, music and writing as well as visual arts. Directed by Holger Cahill ( born in Iceland! ) from 1935 – 1943, he was committed to what he called “cultural democracy”. As I say in my book Art and Politics in the 1930s in my chapter on Cahill: ” Cahill could sell his program to bureaucrats on one day and to a small- town mayor on the next. He could drink tea and play poker, charming both millionaires and Marxists. He spent much of his time as administrator on trains, promoting the art program in small towns across the country. ”

Cahill was immersed in the philosophy of John Dewey and Thorstein Veblen, he believed in the beauty of folk art, the art of everyday life, but he wanted to sponsor a wide range of styles and subject matter.

Here is another quote from my book:

“In August 1935, armed with nostalgic Americanism, Deweyan pragmatism, some Marxism, and a lot of populism, Cahill joined the New Deal bureaucracy. He was anxious to bridge the gap between the creative artist and the government bureaucracy. Recognizing that the support of Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins was crucial, Cahill adopted New Deal rhetoric in his speeches as often as possible. Late in his own life, Cahill paid tribute to Roosevelt: ‘At a time when it looked like our civilization couldn’t afford itself, [President Roosevelt] had the courage to establish the greatest art program in this nation’s history.’ “

Indeed Eleanor was crucial to obtaining ongoing support for the program and manipulating which department funded it, thus keeping it going longer.

.

This crucial tribute to the Roosevelts stands out in contrast to our current atmosphere in the government of greed, self serving political maneuvering, and philistinism.

According to one manual, the Federal Art Project for visual artists included mural painting; easel painting,oils,water colors, drawings, graphic arts; sculpture; applied arts, posters, signs, arts and crafts- metal work, decorative wood carving, ceramics, weaving, photography; lectures, criticism, research, pamphlets and monographs on various phases of American art; circulating exhibitions of art; art teaching; drafting, charts, maps, models, stage design, and restoration. Based on his fervent desire to make the art world more democratic, Cahill promoted two programs that do not appear on this list: the Index of American Design and the Community Art Centers. The first supported the preservation of design, the second took art into communities that had not even seen art much less produced it before particularly in the South and West.

The Community Art Centers reached out specifically to African Americans and included the famous Harlem Art Center, the source of support for so many later to be famous African American aritsts. In the South it bowed to larger forces of racism and set up two separate art centers for Blacks and Whites, but again, many artists began careers there that would later become famous.

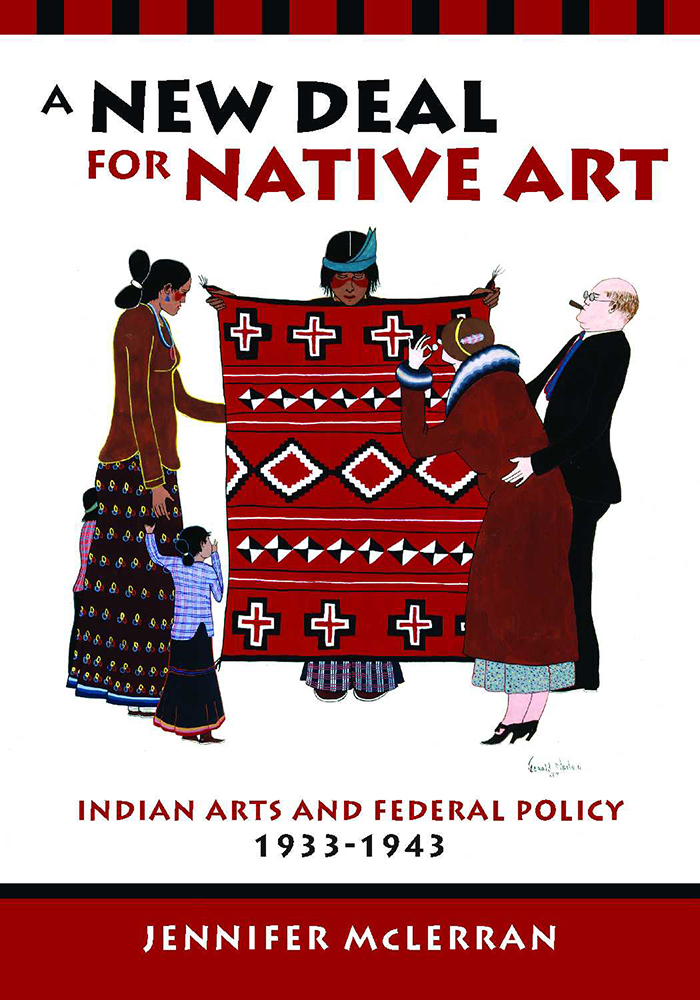

Other New Deal programs reached out to Indigenous artists many of whom also became well known. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 completely changed federal policy toward Natives. In addition to many legal changes, the New Deal supported work for natives as well as art in the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1935. Jennifer McLerran’s points out its strenghts and weaknesses ( particularly in emphasizing a nostalgic reference to the past, a characteristic of the New Deal as a whole).

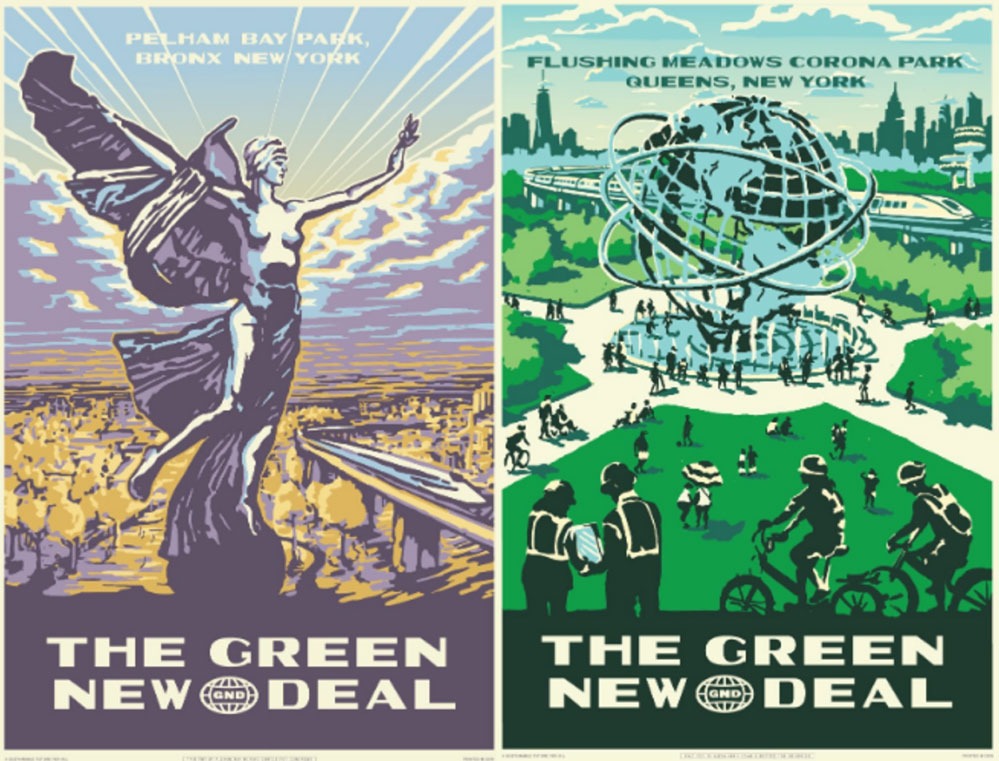

So when today we speak of a new New Deal in anything, art, health, climate, we have to recognize the huge gulf between the liberals and progressives of the Roosevelt administration and our current moment, the divisive gap in our country encouraged by the present administration, is in stark contrast to the efforts to serve the people, to bring people together and to help them survive in the 1930s.

The radical actions of the artists in the early years of the decades before the Roosevelt administration began served as a catapult for the desire to support artists. We need such a catapult from the artists write now, to project into the NEXT ADMINISTRATION. In Italy the artists are organizing.

Hopefully the artists here can do that also.

This entry was posted on May 8, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.