Selma Waldman More Important Than Ever in 2021

“Lust for power and territory is the same lust that kills man, women, children and the land itself” Selma Waldman 2002

What would Seattle’s deeply political artist Selma Waldman think of our current catastrophes?

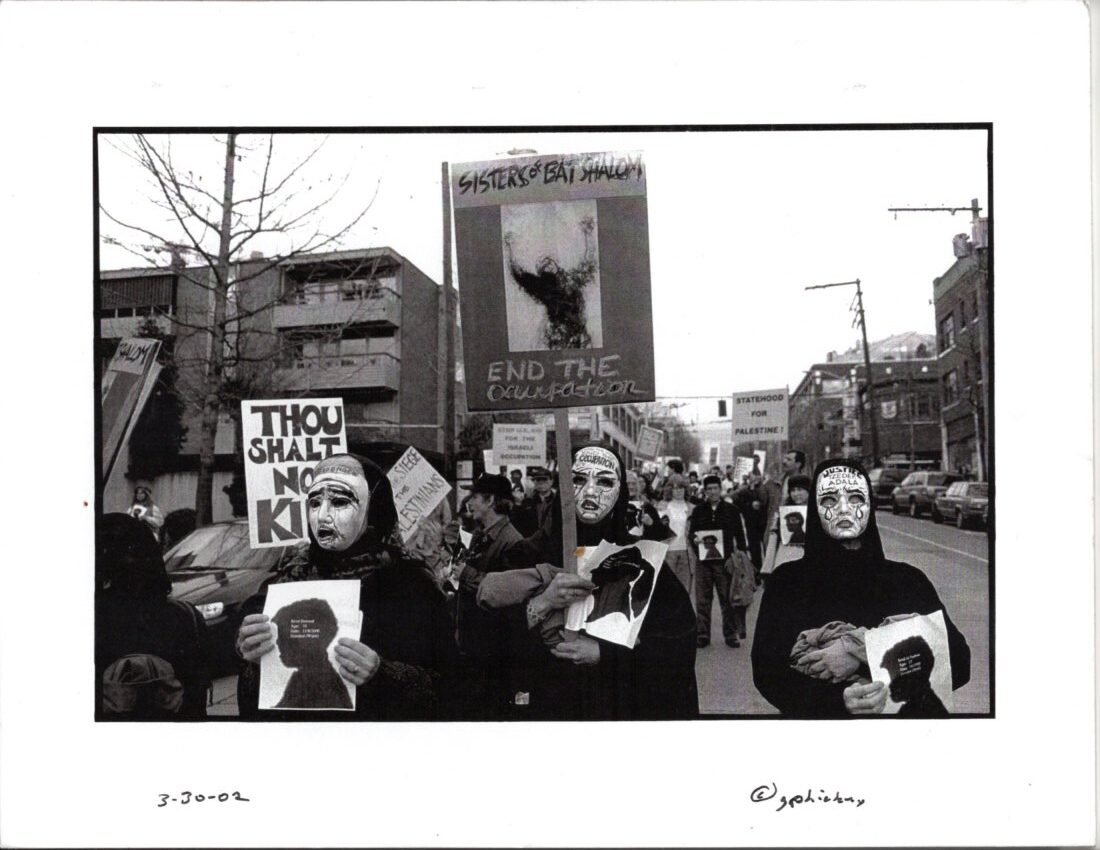

On a bitter winter day in January 2008, I accompanied Selma Waldman to the last demonstration that she attended before her death in April. “Shut Down Guantanamo” began with a demonstration of waterboarding. A young man, tied face down on a board, had a wet towel over his face and water poured over his head into a bucket. Even in the simulation, the volunteer felt as though he was about to drown.

During the speeches that followed by politicians and political activists, we held up enlarged images of one of Selma’s explicit drawings of waterboarding from her long series Black Book of Aggressors. They scrupulously depict in her expressionist drawing technique, several means of waterboarding, with detailed text taken from newspapers. Selma urgently said in my ear, “But it shouldn’t be only Guantanamo, what about the black sites, the other places of torture.” She always understood that one place is connected to so many other places; one manifestation of torture connects to the will to power everywhere, the will to oppress, the desire to destroy the human spirit.

“A Conversation in Time and Space” presents thirteen of Selma Waldman’s monumental drawings at the Center on Contemporary Art partnered with nine brave COCA members responding to her forceful work and statements with their own art and commentaries (all of which can be seen and read on the COCA website https://cocaseattle.org/time-and-space until February 20).

Naked Aggression Heavy Cable

Waldman’s art embraces the classical tradition of Käthe Kollwitz in her expressionist line. The materials of chalk and charcoal were part of her politics as well, a metaphor for the fragility of life.

How ironic that this timely exhibition cannot be visited in person. The current disasters we face, COVID-19, climate change, homelessness and hunger, intersect with the abuses Waldman addresses: torture, detentions, endless wars, starvation.

So we can answer the question: she would immediately call attention to these intersections all seated in an obsession with power, what she called “Naked/Aggression.”

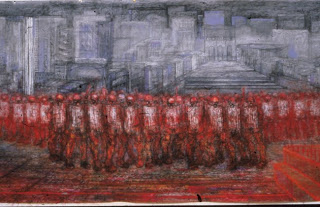

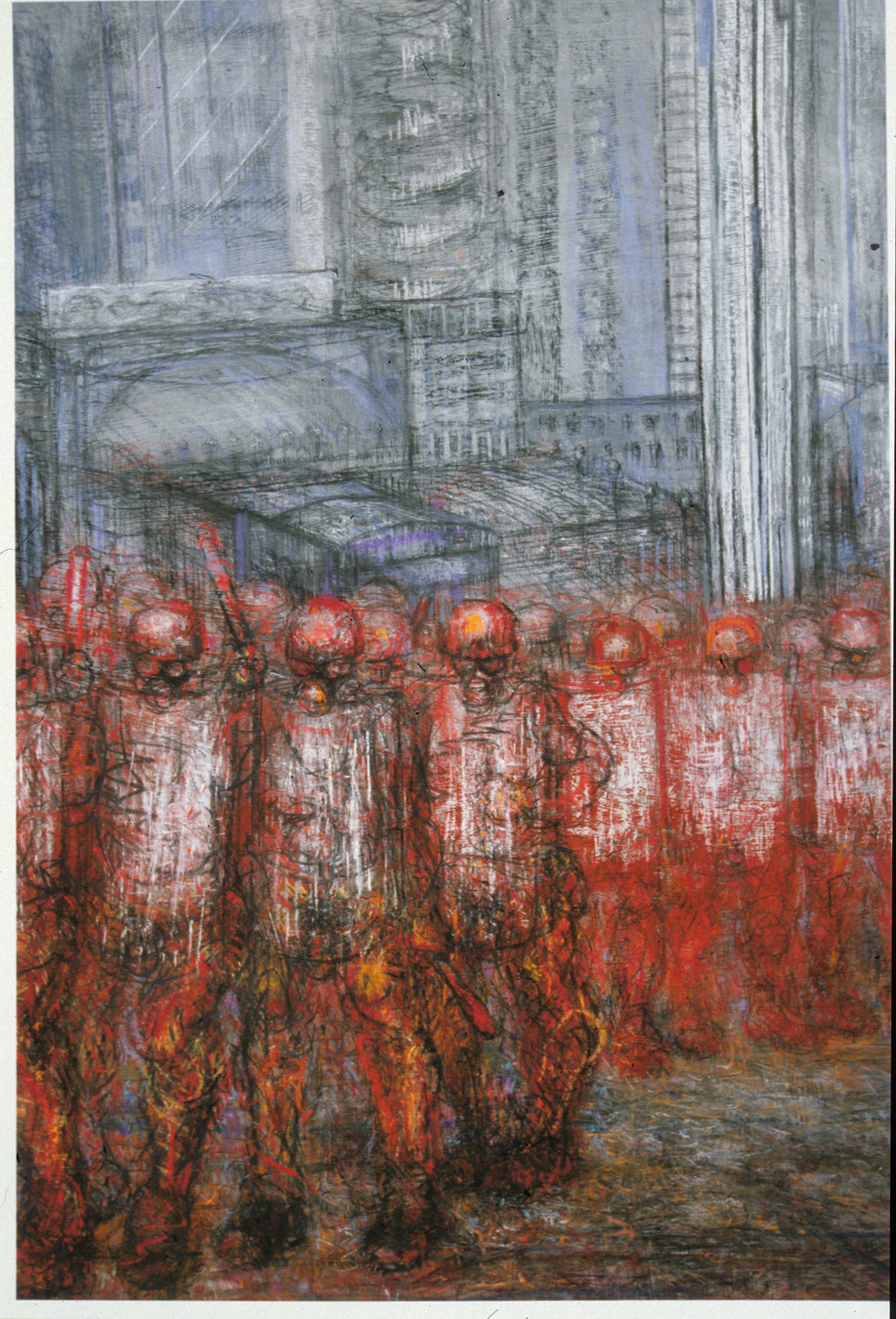

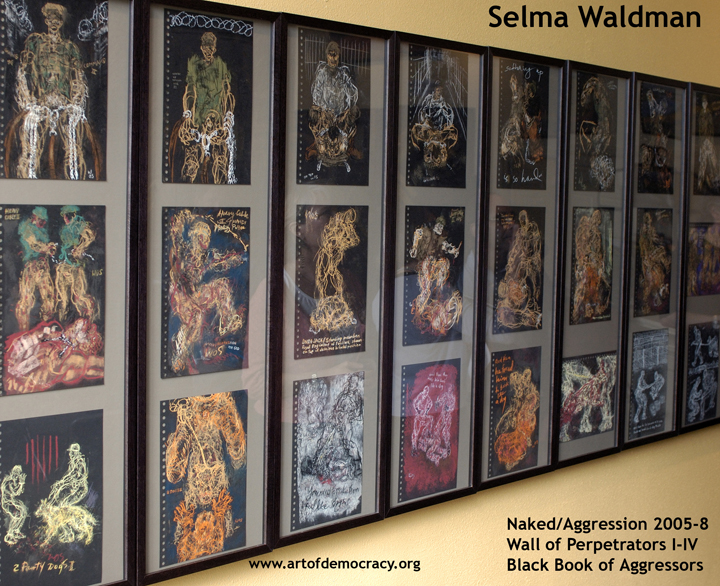

Rainer Waldman Adkins carefully selected the works to touch on large themes in his mother’s work: the Holocaust series called Falling Man Suite from 1966, The Man and Bread series, featuring extreme desperation in famine, police brutality in The Thin Naked Line, drawn after the 1999 World Trade protests in Seattle and the aggressions of war, in nine images from the over 80 works in the “Black Book of Aggressors,” in the long cycle called Naked/Aggression-Profile of the Armed Perpetrators first begun in the late 1990s.

Waldman grew up in Kingsville, Texas, deep in South Texas, where everyone was employed by the mighty King Ranch. The giant cattle ranch employed hundreds of Chicano workers. She belonged to the only Jewish family in the town. Although her own family was middle class, she learned about oppression as a way of life in her early years from Chicano/a friends.

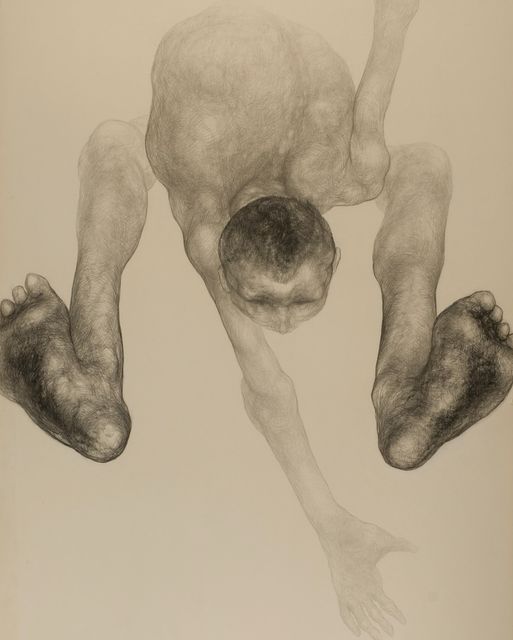

When Waldman was on a Fulbright Fellowship in Berlin, she was profoundly affected by the 1960 documentary Mein Kampf. She began a series of drawings of dehumanized and distorted figures based on images and accounts of the Warsaw ghetto. These are the first works on the Nazi holocaust by a Jewish American artist to be acquired by a German museum.

Collectively titled Falling Man, the ninety drawings are near life-size representations that were dramatically hung from the ceiling and stairwell of the Jewish Museum in Berlin. This is the source of the Falling Man Series, represented with one huge drawing at COCA called “The Doll.” The helplessness of the naked figure brings us directly to our current crisis as so many people lose their homes and live in the streets in desperation.

The “Man and Bread” drawings of the late 1960s take the Falling Man series to brother against brother, a fragment of the wretchedness inflicted on so many masses of people. The two Bread drawings in the exhibition come from a group of more than 300 works (of which 25 are in the Collection of the Memorial Terezin Ghetto Museum). Waldman based the imagery on Elie Wiesel’s descriptions in Night (Bantam Books, 1960) of the struggle for food to the death in concentration camps.

On March 21, 1960, Selma Waldman saw the front page photographs of the Sharpeville Massacre, in South Africa. She was so shocked that she decided to more deeply commit her art to a “struggle to end genocide and racism.” We can draw a direct line to our current atrocities in the United States and elsewhere, by the military, the police and most recently armed militias, many of whom are psychologically damaged war veterans.

Police brutality in the large drawing Thin Naked Line, 1999-2002, based on press photographs, gives us the faceless mass of the Seattle riot police who attacked the anti-World Trade Organization demonstrators in 1999. But the drawing refers to mass police assault anywhere. They are dehumanized warriors who advance toward us as a group.

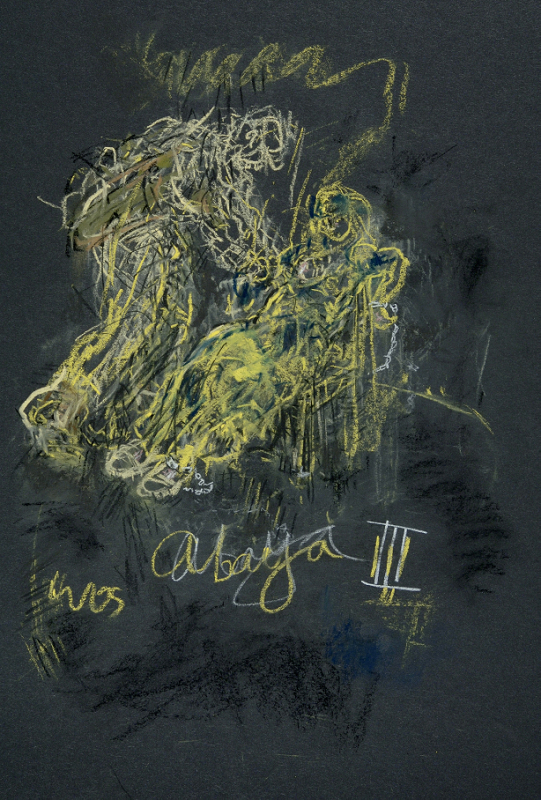

Black Book II 29 Abaya

Finally, her last series Naked /Aggression: Wall of Perpetrators IV-V, The Black Book of Aggressors (I-IV) (2005-2006) bears witness to the degradation of human beings and the systematic abuse of power in Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo, and elsewhere. Left unfinished at the time of the artist’s death in April 2008, the Black Book of Aggressors would have included two hundred drawings and eight walls. For the final wall, she planned to reconfigure Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son (1820 – 23), The Colossus (1808-1812), and other black paintings, to address atrocities world-wide.

As she wrote

“the cycle ‘corrects’ the mythic profile of the invulnerable warrior-hero, born to fight and trained to win – and reveals it as a reckless existential lie and an obscene fraud without which battles could never be engaged- confirms it as the fool’s proof of manhood, the lifeblood for fascist, the main meat dished out to defense profiteers, and the first refuge for scoundrel fanatics.”

What could be a more timely statement given what we have just witnessed in the US capital!

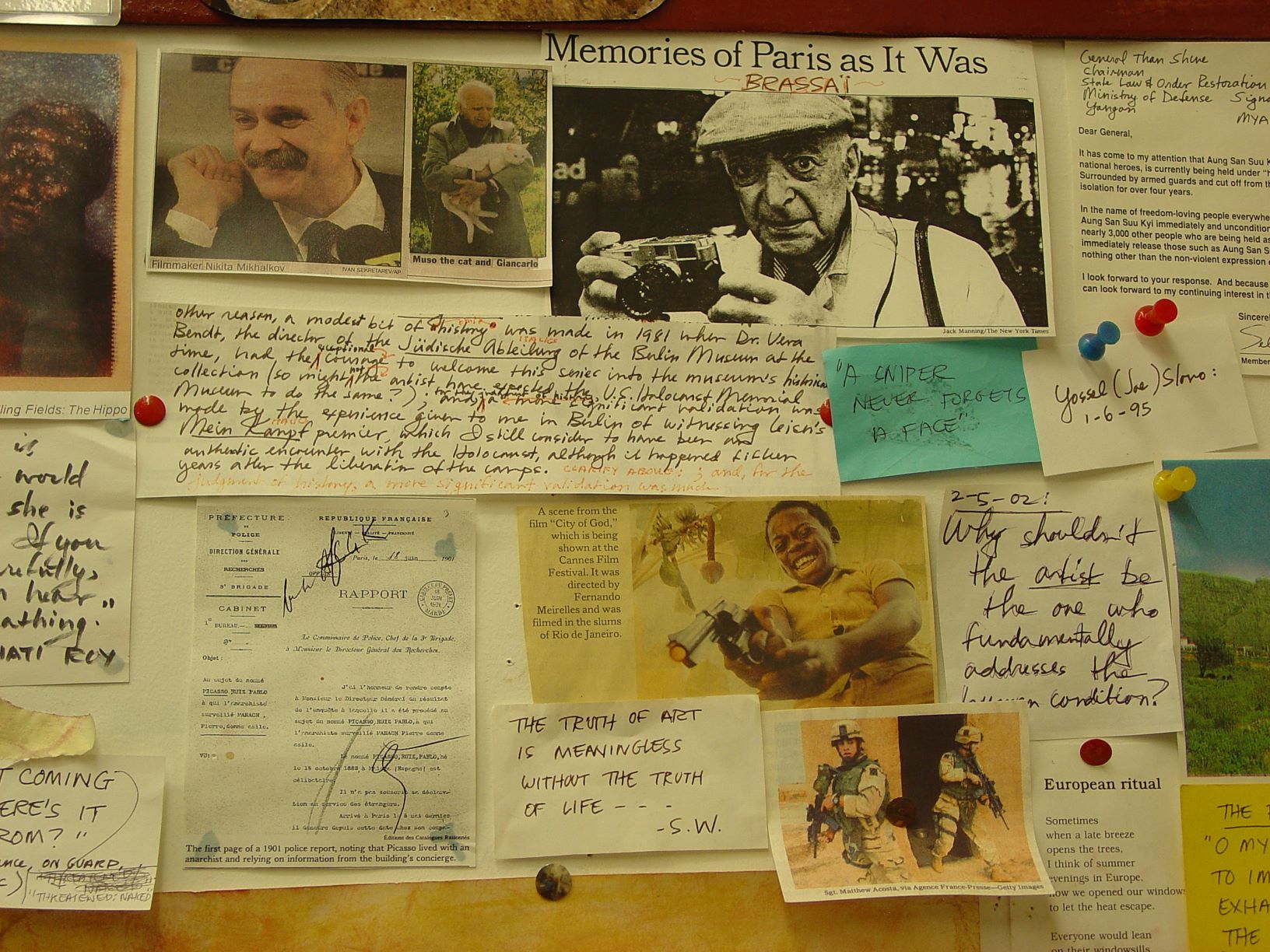

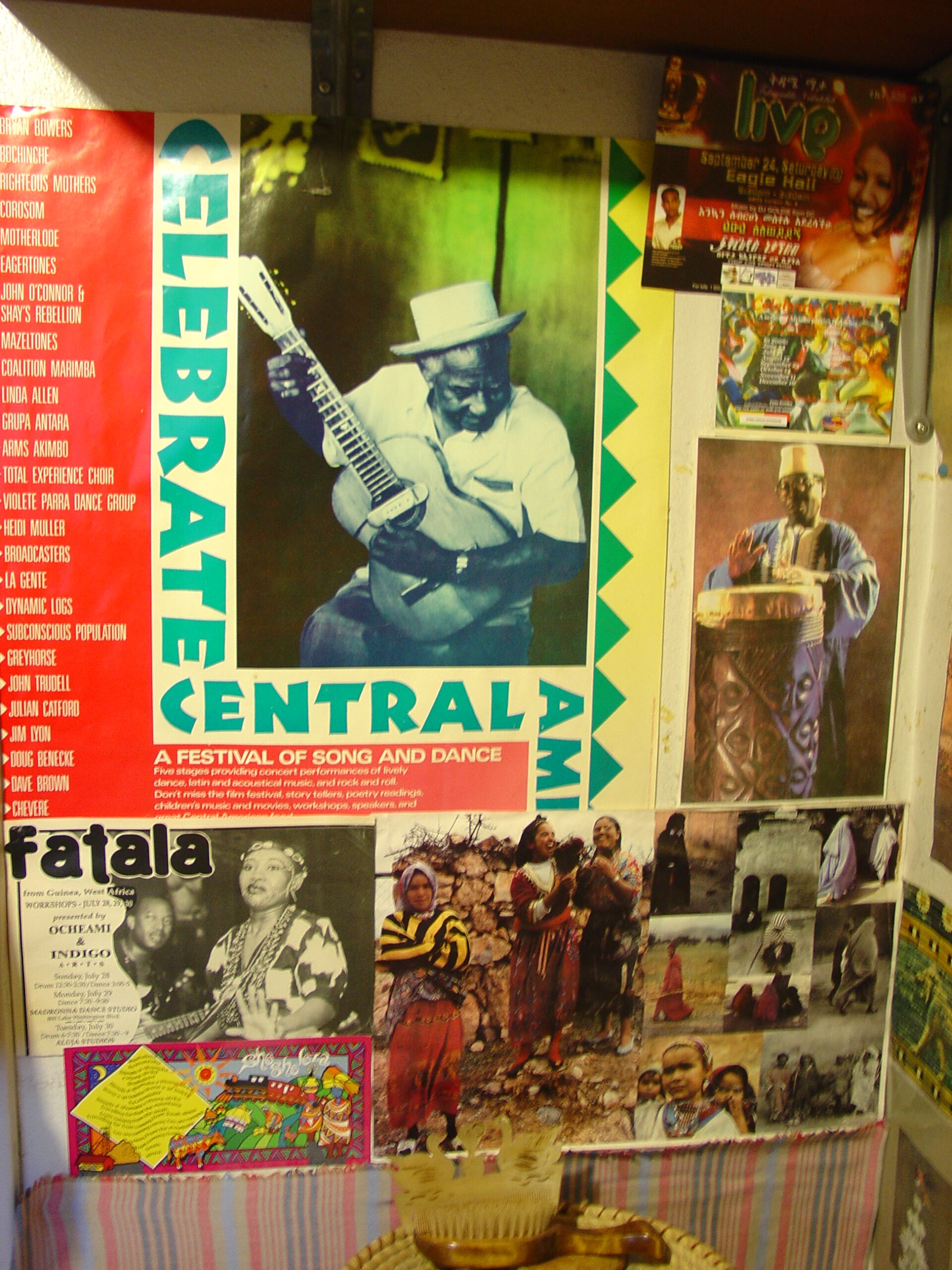

Every detail of Selma Waldman’s life carried her strong spirit of resistance and her belief that creative voices could win over forces of oppression. In her small home in Rainier Valley every wall was covered with art, texts, poems, posters, prints, photographs. There were photographs of singers, dancers, gymnasts, poets, and writers, as well as quotations, and her own writings. Every wall and most of the floor space was filled with books.

But two facts emerged clearly for me as I spent more time in her house in her last weeks. First, her witness to depravity and the abuse of power was paired with a celebration of the human spirit in all of its glorious powers of creativity and resistance. Second, Selma herself, lucid to the end, was immersed in a continuous remembrance of the holocaust itself, the initial horror that she experienced not first-hand, but deeply, at a critical time in her life.

She spent her life searching for archetypes that could represent the underlying loss of humanity that leads to such abuse.

Selma Waldman would answer the question with which I began by speaking of the intersections of past and present, all seated in an obsession with power manifested as racism, fanaticism, and inhumanity.

But she always paired her witness to depravity and the abuse of power with a celebration of the human spirit in all of its glorious powers of creativity and resistance.

This entry was posted on February 26, 2021 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.