Port Townsend marks its history with Indigenous groups

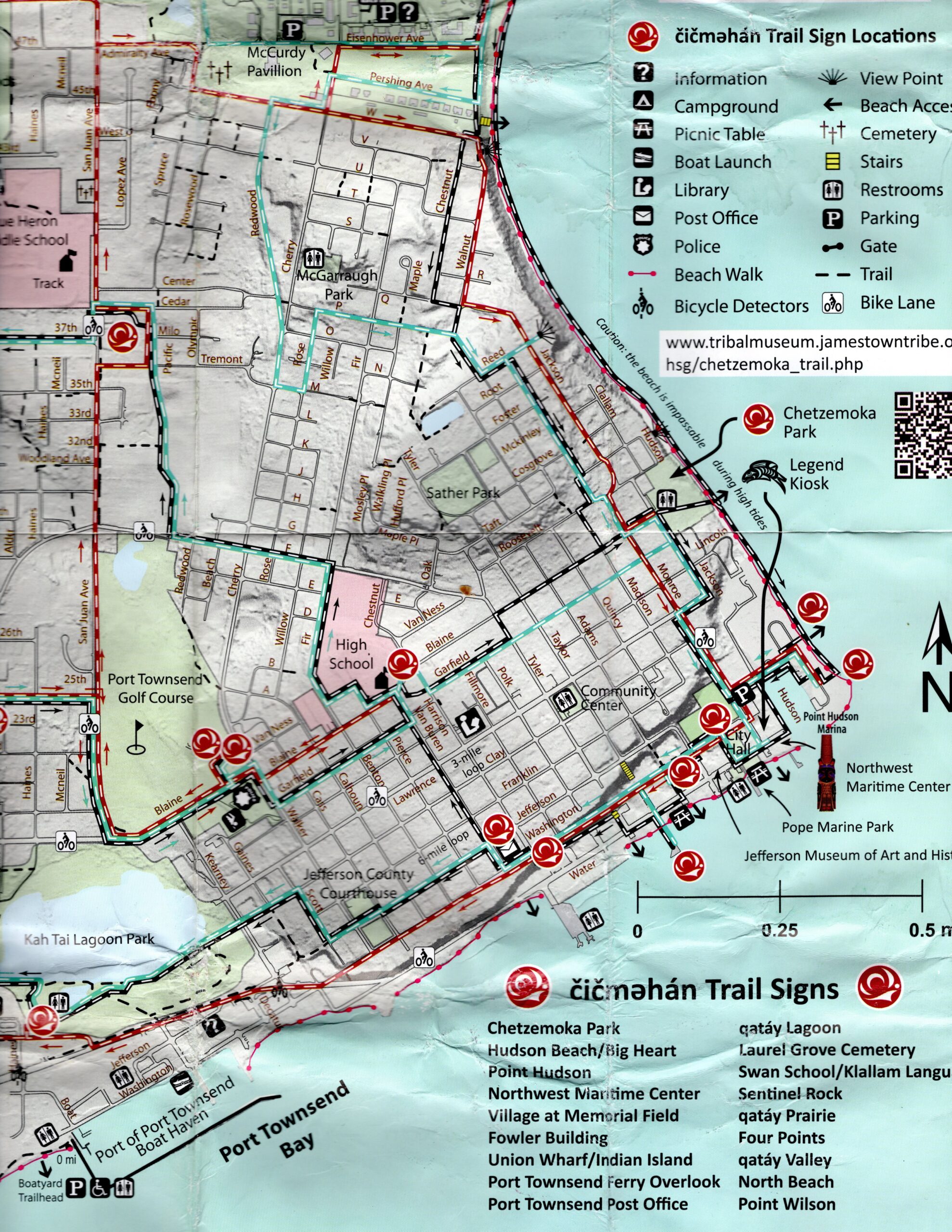

And what a horrifying history it is ! The čičməhán (Chetzemoka) Trail. named after čičməhán(Cheech-ma-han) the great leader of the Klallam tells that story in all its vivid detail. Here is an overview of part of the trail. It includes most of the sites that we found ( we were driving and walking). But aside from the natural beauty of Port Townsend, it was quite a revelation to read this history.

The first site we went to was at the North end of downtown Port Townsend

It told the story of “Chetzemoka’s Big Heart, a story by Mary Ann Lambert of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe’s Lambert/ Reyes family (1879-1966, also the author of The 7 Brothers of the House of Ste-Tee-Thlum). It illustrates Chetzemoka’s heart, and the power and respect he commanded.”

An army garrison was built on this site in 1856 ( see next sign, this was one year after the Treaty of Point No Point) to “quell Indian rioting” As it turned out it was the soldiers who created the problem:

“However, the soldiers were known to frequent the saloons of Port Townsend and overindulge. One day two drunken soldiers, realizing they had overstayed their leave, stole an Indian canoe from the S’Klallam village at Point Hudson, and subsequently drowned when a southeast squall arose across the bay.

Townspeople assumed that the soldiers had been killed by Indians, and when a youth named Tommy Shapkin found one of the soldier’s bodies on the shoreline and donned his cap and jacket, he was accused of murder. He was jailed and a hanging scaffold was built. When the youth was brought to the platform, another S’Klallam youth ran to find Chetzemoka.

Forcing his way through the dumbfounded crowd, Chetzemoka approached the scaffold. Without a word he mounted the steps and reaching into his belt the Duke of York [as he was nicknamed] withdrew a knife, reached up and cut the knotted noose and threw it upon the ground below. Then removing the blindfold from the boy’s eyes, he said “Go, my kinsman. You are free!” Turning and facing the astonished crowd, Chetzemoka said (in Chinook), “Friends, this is Indian Country, our country. There never was a time when it was not our country. We are Klallams. Once we were strong, proud people. Because of sickness and death, we have diminished in numbers until now we are no longer a strong people.

But we are a proud people. We will not be the first to spill Boston blood upon our beloved land. You Bostons are a strong people. Do you wish to be the first to spill Klallam blood upon this soil which once belonged to us? Have you no pride?” “Bostons,” he continued, “We have been friends. Let us remain friends. If this unwise act which you were about to commit is what you call civilization, then give us back our way of life. Oh, White People, our brothers under the skin, do not let this happen again.”

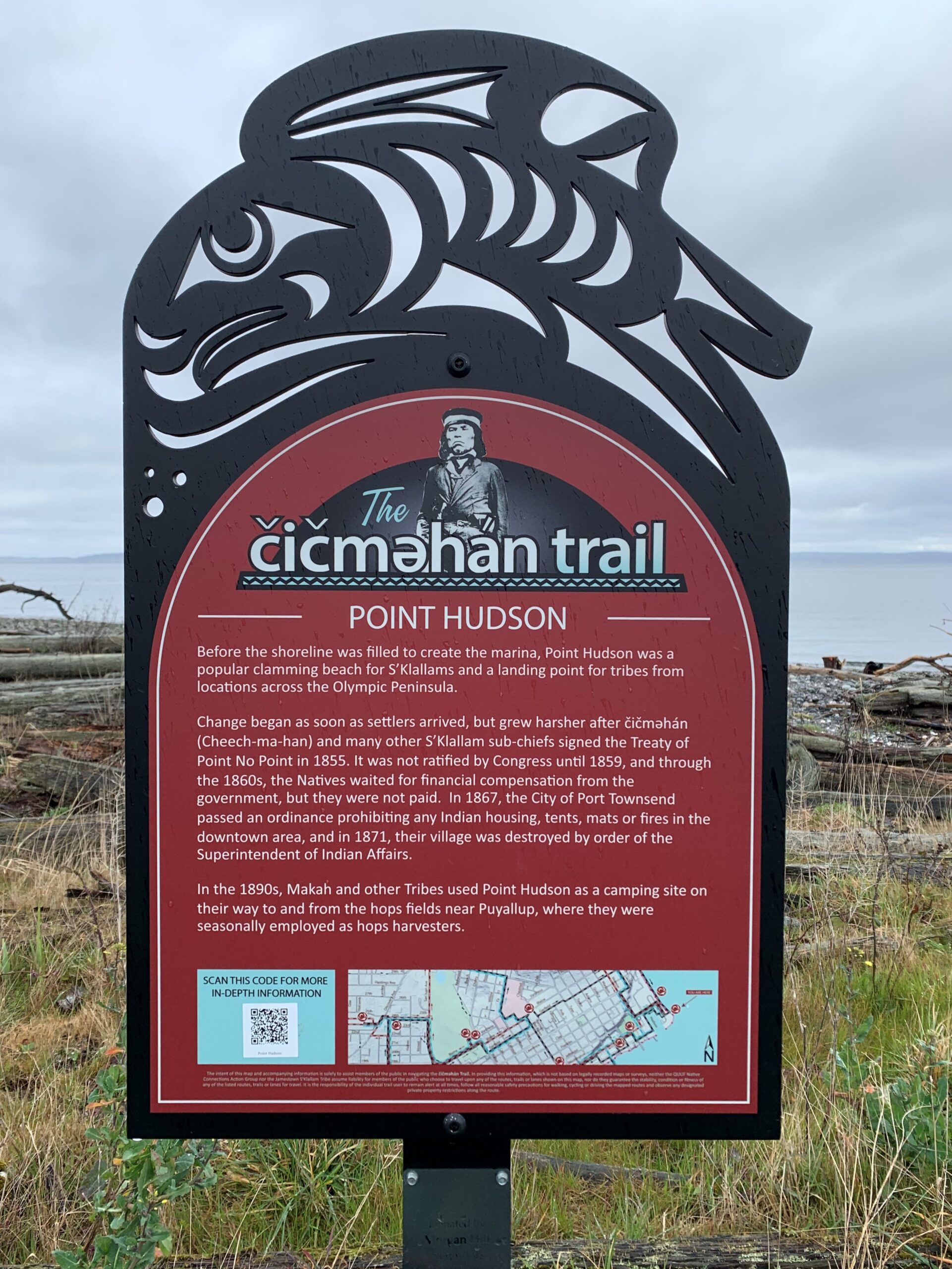

The site where he stood was an Indian village until white men arrived. This sign at the point reads

“Before the shoreline was altered to create the marina, Point Hudson was a popular clamming beach for S’Klallams and a landing point for tribes from locations across the Olympic Peninsula.

Change began as soon as settlers arrived, but grew harsher after čičməhán (Cheech-ma-han) and many other S’Klallam sub-chiefs signed the Treaty of Point No Point in 1855. It was not ratified by Congress until 1859, and through the 1860s, the Natives waited for financial compensation from the government, but they were not paid. In 1867, the City of Port Townsend passed an ordinance prohibiting any Indian housing, tents, mats or fires in the downtown area, and in 1871, their village was destroyed by fire, by order of the Superintendent of Indian Affairs.

In the 1890s, Makah and other Tribes used Point Hudson as a camping site on their way to and from the hops fields near Puyallup, where they were seasonally employed as hops harvesters.” On the link to the text are old photographs of tribal groups camping on the point in the late nineteenth century, after the original village was destroyed by fire.

Grandma Newman Drying Salmon at Pt Hudson.

As we headed downtown, we saw a new totem created in honor of the creation of the trail outside the Northwest Maritime Center. It gave a lift to our spirits from the sad story of the destruction of the villages on Hudson Point

Here the sign reads

“The Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, like the Northwest Maritime Center, is a contemporary organization with a tremendous appreciation of our seafaring history and respect for those who have preserved and shared their knowledge throughout the centuries.

The sea is all around us on the Olympic Peninsula: the sound of the tides and seabirds; the salty aroma in the air; the edible abundance that has sustained us for millennia; the navigable waterways that allowed us to move freely among and between our villages and our neighbors. For the S’Klallam people, the sea is a major character; the backdrop of our lives. And we know that we share that deep sentiment with those who have devoted themselves to creating and sustaining the Northwest Maritime Center

It is with that sentiment of shared vision that the Tribe and the Center agreed that a totem pole and a canoe carved of Western Red Cedar, and an interpretive sign about Coast Salish Canoe Culture were appropriate symbols of our shared interests and ongoing partnership in the 21st century.”

Nootka “Chinook” style canoe created for food and natural resource gathering also for fishing, seal hunting and whaling. Used by many tribes along the coast.

From the website

“Outside the Northwest Maritime Center you will see the 26’ totem pole carved by Dale Faulstich, Andy Pitts, Tyler Faulstich, and Tribal citizen Timothy O’Connell. You will also see the Coast Salish Canoe Culture sign, and a traditional canoe hanging in The Chandlery.

The totem pole pays homage to millennia of finely crafted wooden boats and the artisans who built them. It features, starting at the top, the Supernatural Carpenter, the Spirit of the Cedar Tree, čičməhán with his arms in the welcoming posture, standing on Sentinel Rock.”

The next site was called “The Village at Memorial Field.” Today it is near a playing field. It is the site of the original village

“The village of qatáy once sat near the bluff at what is now the corner of Monroe and Water Streets. It was the principal village of S’Klallam people at the time of the treaty signing, and home to their Chief, čičməhán (Cheech-ma-han).

James Swan’s 1859 census showed “300 whites and 200 Klallams” living in Port Townsend. qatáy village was burned on August 23, 1871 by order of the federal government, prompted by complaints from the settlers. Destruction of the village of qatáy forced many of the S’Klallam to move to the Skokomish Reservation, Port Gamble, Port Discovery, or to join family in Dungeness (stətíɬəm), who would purchase land at Jamestown in 1874. Others, including cicm?hán and his family, moved across Port Townsend Bay to Indian Island, where villages had been located for hundreds of years.

Many S’Klallam adjusted to non-Indian communities, working at local mills, on farms, fishing and providing water transportation to settlers on land and waters that had always been Native homeland.”

For more details on the destruction and removal of the Indians in the village in 1871 see the website. text for this site. It is full of horrifying details as well as photographs of the era.

Nearby is the “Fowler Building.”

“Port Townsend’s first stone building was completed in 1874 for Enoch S. Fowler.

Fowler was a ship captain who transported Governor Stevens and his treaty negotiators from place to place, including Point No Point in 1855, where Stevens, Fowler and čičməhán (Cheech-ma-han) convinced the Natives to trust the whites and affix their “X” mark to the Treaty. Under considerable pressure, the tribes ceded their rights to nearly 440,000 acres of land, receiving in return a 3,480-acre reservation on Hood Canal, the “right of taking fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations,” and $60,000 payable over 20 years.

When čičməhán died on Indian Island in June 1888, his sons brought his body into town by cedar canoe. Townspeople honored their old friend, who had prevented conflict to save his people, by laying his body in state in the Fowler Building’s main parlor for two days, where settlers paid their respects prior to his burial at Laurel Grove Cemetery.”

But it gets worse. After removing the Indians to Indian Island, they were then removed from Indian Island at the beginning of World War II.

The next stop was called Union wharf/Indian Island

“Looking south, view Kilisut Harbor and Indian Island (now Naval Magazine Indian Island). Archeological evidence shows that Indian Island was an important location to the ancestors of the S’Klallam and Chimacum people for over 1,500 years. For many centuries, sea level was as much as 7 meters lower than today, making the harbor a fertile wetland.

In 1870,čičməhán (Cheech-ma-han) met with a Territorial delegate, asking that the Tribe be given Indian Island as the S’Klallam reservation, but that request was denied.

čičməhán and his family, including his two sons Charlie Swan York and Prince of Wales, moved to the village at the northeast corner of Indian Island called šéʔnəkw, after being forcibly removed to the S’Klallam Indian Agency (the Skokomish Reservation in Hood Canal) from Port Townsend in 1871.

Real estate records show that in 1887, a parcel of land was sold by Catherine McCurdy to pačwíɬəs (Prince of Wales) and Charlie York, the sons of čičməhán, and to James Webster (Chimacum Jim) and his wife Louise, whose descendants are citizens of today’s Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe. In 1888, pačwíɬəs purchased additional land at šéʔnəkw from Ms. McCurdy and maintained ownership and residency there until 1941.

Indian-owned lands on Indian Island were lost when the federal government took it through the Eminent Domain process in 1939-41, to convert the island into a Naval base.”

It is still a military zone today.

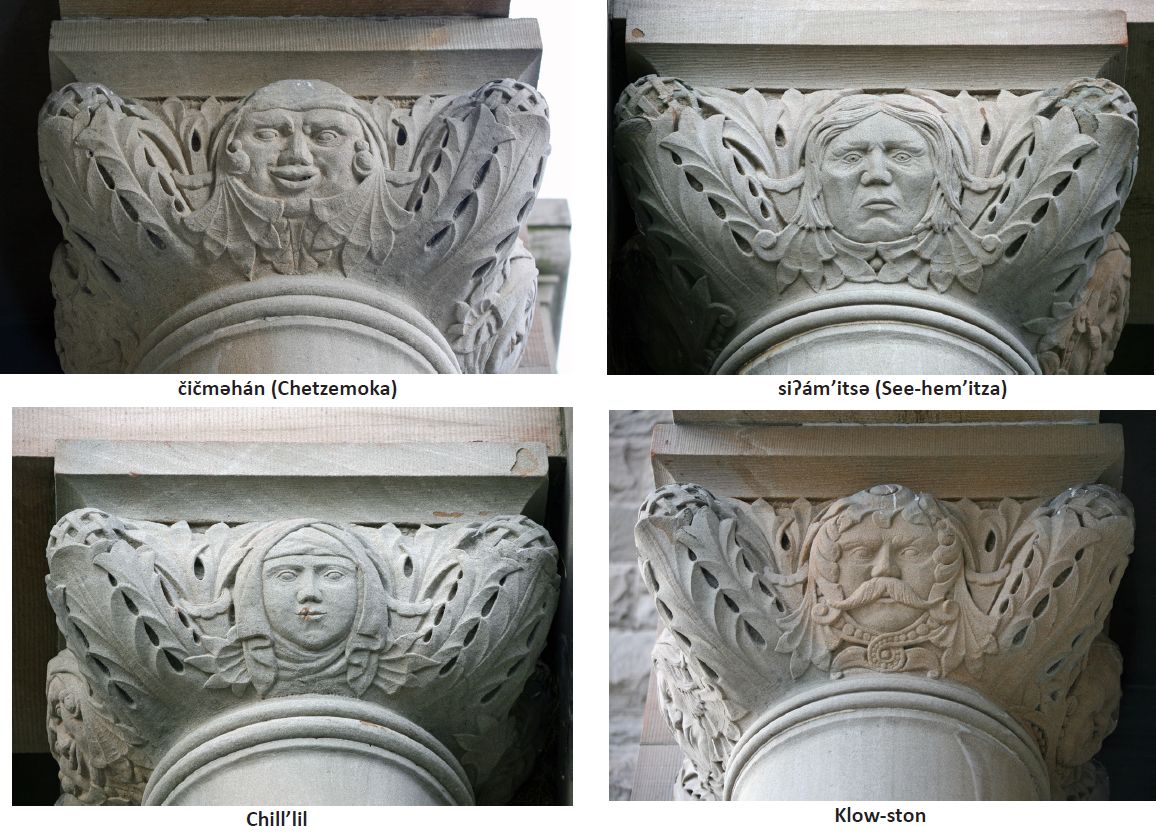

We missed a site downtown here near the ferry dock, but we went to the Post Office where the chief and his family are incised in the capitals of a Richardsonian Romanesque style post office. Here they are from website:

I find this a little grotesque, that after destroying their culture they put them into stone capitals, another form of colonization.

“čičməhán (Cheech-ma-han) inherited his role as chief when his brother Klow-ston left the area, and he was officially recognized as “Chief of the Klallams” by the federal government in 1854.

When settlers Hastings and Pettygrove first arrived in 1851 and met čičməhán, they sent him to San Francisco to reinforce his understanding of coming changes (in population and technology). His tour guide was James G. Swan, with whom he became a lifelong friend. In 1859 Swan wrote that čičməhán returned from San Francisco “with very enlarged views of the number and power of the white man.” The trip provided by the new settlers seemed to sober the Chief, who tried to mediate between the whites and Natives from that point on.”

The post office was built five years after his death. I wonder how much he lived with regrets for trying to “mediate” with whites who betrayed his people over and over.

From downtown we went to Fort Worden, Point Wilson, where Admiralty Inlet and the Straits of Juan de Fuca collide. A dramatic tale of a whirlpool awaited us there.

From the sign you see Henry standing near.

“There is a whirlpool on the side of this lighthouse point. Some people from Hadlock were over at K’l’w’l’’m, and a girl there met a monster (he was a shark and she did not know it). She fell so madly in love with him that she used to go down through that whirlpool to visit him. She used to come back at times to visit her folks at Hadlock. When she would come to visit her folks, she would bring home all varieties of food from the bottom of the bay; big swells would come ashore with her, and it wasn’t until kelp was growing on her forehead that her father told her not to come back any more. Before that, her folks had permitted her to come, for she had brought them food at times.”

Next we went to North Beach where we had lunch and learned that the Indians carried their canoes around this dangerous point.

The last place we went to was qatáy (kah-tai) Valley,

“This site is the last remaining vestige of the natural prairie that spanned the qatáy (kah-tai) Valley, between wetland areas. Relatively dry, upland areas of the valley provided camas bulbs (qwɬúʔi in Klallam and Camassia quamash in Latin) for S’Klallam people to eat. The 1.4-acre camas prairie was officially preserved by the Olympic Peninsula Chapter of the Washington Native Plant Society in 1987.

Camas harvesting was done by women, who broke ground with digging sticks (generally made of fire-hardened Ironwood, or Ocean Spray). They had to be well aware of the difference between blue and white (death) camas, in order to harvest only the edible variety. They turned over a section of ground, pulled out the largest camas bulbs, and returned the earth to its original spot to continue growing.

The bulb of blue camas, a main carbohydrate of the S’Klallam diet, was roasted and ground into a starch that could be stored for winter. Radiocarbon dates from camas ovens at Ebey’s Prairie, on Whidbey Island directly across Admiralty Inlet from Port Townsend, suggests these traditional cooking methods are at least 2,000 years old.”

There were six other sites that we missed for various reasons. You can read about them all on the website.

Over all it is a story of terrible betrayal. I can no longer look at the Victorian architecture of Port Townsend. All I see is the death and destruction of a culture that laid the foundation for the death and destruction of our planet that we are dealing with today. Apparently though Chetzemoka has dozens of descendents today, so the Natives survived through incredible odds. Here is what was placed on his gravestone:

Chetzemoka (Duke of York)

June 21, 1888

The white man’s friend;

we honor his name.

This entry was posted on April 6, 2021 and is filed under Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, ecology, Indigenous History, Uncategorized.