Ghost of a Dream and Elizabeth ‘Mumbet’ Freeman

“Any time, any time while I was a slave, if one minute’s freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told that I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it, just to stand one minute on God’s earth a free woman, I would.” Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman

Joana Vasconcelos, “Valkyrie Mumbet,” 2020, 384 x 672 x 504”,Stephen D. Paine Gallery all photos of Valkyrie by Will Howcroft. Courtesy MassArt

Ghost of a Dream, “Yesterday Is Here”, through December, 2021

Gudrun Arsaelsdorrit Edelsten and Lynn Puritz Warner Lobby all photogs of Yesterday is Here by Daniel Berube ’21.

Courtesy MassArt. (3)

Installation views at MassArt Art Museum, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Boston, MA

I have once again invited my good friend in Boston, Pamela Allara. to provide a post! The shows are up until the end of December.

The gallery at Massachusetts College of Design in Boston has always held innovative exhibitions, but in an inadequate space that frequently dulled its impact. In February, 2020, MassArt Art Museum,(MAAM) held a grand opening for its new gallery, a large, airy, two-story space with its very own entrance for the first time! Unfortunately, March, 2020 followed closely thereafter, and the beautiful space has been closed until its recent re-opening on October 9.

Don’t miss the two exciting exhibits now open, one in the lobby/reception area and the other in the main space. They are well worth a visit both for their intrinsic aesthetic value and for the introduction they provide to the work of less familiar artists.

Ghost of a Dream is an artists’ collective based in Wassaic, New York. Led by Adam Eckstrom, GoaD sponsors Art for Artists (www.artforartists.org), an invitational, curated art exchange, as well as an ‘edition exchange’ which includes works for sale. (The latter have been donated to the Southern Poverty Law Center and elsewhere).The collective makes works from ephemera that center, in their words, “on people’s hopes and dreams.”

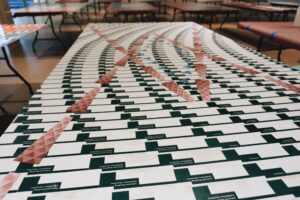

As the MAAM looks to the future, GoaD reminded visitors that the new exhibition program should not entail leaving the past behind. On the lobby’s walls they installed a collage created from cut-up and spliced-together images from over 30 years of MAAM’s exhibit catalogs and announcements. Combined into geometric patterns on the wall, they created a handsome, site-specific installation, “Yesterday Is Here,” that caused the viewer to pause and acknowledge the important work the gallery has done before seeing the new work in the main space.

The multi-media work installed upstairs, “Valkyrie Mumbet,” is both monumental and intimate. Its tentacles spanning the entire two-story gallery almost like a giant octopus, it might have been threatening if it were not apparent that the delicate artwork had been constructed out of crochet, embroidery and fabrics, including capulanas from Mozambique, where the artist’s parents grew up. Also known as African wax print or Dutch Wax cloth, European traders mass-produced and profited from capulanas, but more recently they have been reclaimed by local designers in Mozambique. As the exhibit label points out, the cloths “…exemplify the fluidity of cultures and reflect a complicated and intertwined history of cultural exchanges across continents, as well as the legacy of European exploitation, colonization, and slaveholding.”

Vasconcelos is among a number of contemporary artists using fabric and crocheted cloths in their work to reference culture and history: Ernesto Neto, Ibrahim Mahama, Nick Cave and Olafur Eliasson, among others.

When the gallery, which is on the second floor of the building, was renovated, the 1906 steel vaulting and girders were exposed, which allows artwork to be suspended from the ceiling, as in this instance. From below, “Valkyrie Mumbet” seems to float, increasing the sense of its delicacy.

As we approach for a closer look at the ‘tentacles,’ the variety of the swatches of hand-embroidered and crocheted fabrics remind us of the history of women’s craft work, undervalued for its historical and aesthetic significance until recently. Clearly these fabrics have stories to tell us, but what are they? It will be important to read the label more carefully than usual. So much for skimming!

The work is part of Vasconcelos’ ongoing Valkyries series, which honors inspiring women and has been shown at the Venice Biennale and other prominent venues.

Surprisingly, this is the first U.S. exhibit of any of her multi-media work. When she was approached by Lisa Tung, Executive Director and curator at MAAM to create a site-specific installation, Vasconcelos requested information about notable women from Boston’s history.

According to the account of the staff they provided her with

“a list of individuals whose legacies include suffrage, poetry, charity, cycling, nursing, and activism among others. Vasconcelos was strongly drawn to Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman’s story and wanted to honor her. This monumental installation is the artist’s own distinctive homage to Freeman”

Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman, was an enslaved woman who in 1781 sued the state under the Massachusetts’ Constitution’s Bill of Rights, which stated that “all men are born free and equal.” Between 1764 and 1780, 30 enslaved people had sued for their freedom citing the Constitution, but Freeman was the first to sue under a ‘natural right to freedom.’ Despite the fact that slavery was still legal in Massachusetts, and moreover, “men” meant white men, she won her suit and was freed.

Subsequently, she purchased a home in Stockbridge, MA, where she lived comfortably until her death in 1829. Her eloquent statement explaining the reason for her suit is memorable: “Any time, any time while I was a slave, if one minute’s freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told that I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it, just to stand one minute on God’s earth a free woman, I would.”

Given the context, the fact that the work floats rather than being adhered to the flooring, and that the tentacles reach out and up, even to the second-floor balcony, underscores the theme of seeking freedom. Again, in that context, each patch of fabric or handwork becomes the record of an enslaved individual, part of their clothing or of cloths used for cleaning, as well as fabric referencing colonial histories. History is made concrete.

This entry was posted on November 11, 2021 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Feminism, Uncategorized.