Kenjiro Nomura American Modernist

“Kenjiro Nomura American Modernist, An Issei Artist’s Journey” (Cascadia Art Museum, Edmonds, to February 20)

“Kenjiro Nomura American Modernist, An Issei Artist’s Journey” (Cascadia Art Museum, Edmonds, to February 20)

Kenjiro Nomura (1896 – 1956) came from Japan to Tacoma at the age of ten in 1907. while living in Tacoma as a child, he attended a Japanese Language school where he was fortunate to have a skilled teacher who taught him “graphic skill and developing aesthetic sensibility that served him well in adulthood.” ( Barbara Johns Kenjiro Nomura American Modernist p 14)

When he was barely seventeen his parents returned to Japan leaving him to fend for himself. He managed to not only survive but to find art training and then to be recognized as an artist. He moved to Seattle from Tacoma when he was 19 and began to study art with Fokko Tadama who had recently relocated from New York City bringing East Coast styles with him.

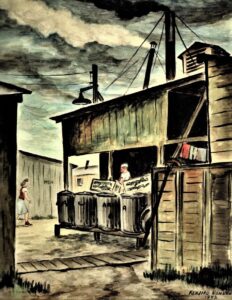

Nomura supported himself with his own sign painting business in the Nihonmachi, the heart of the Japanese immigrant community. As discussed in Barbara Johns excellent book of the same title as the exhibition, Nihonmachi provided a rich cultural environment.

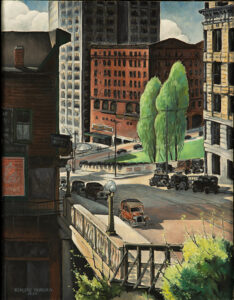

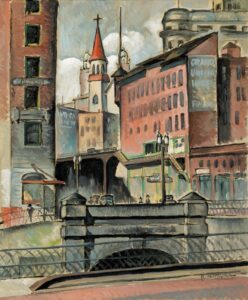

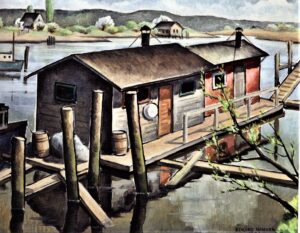

Nomura made a major contribution to American scene painting with his 1930s urban street scenes. He carefully observed complex intersections in such familiar locations as 4th and Yesler.

By the end of the decade Nomura was acknowledged as a major artist. His original take on the idea of American scene with its complex composition and spatial relationships makes his work distinct and in some ways more sophisticated than his contemporaries like Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood. Although here we see no obvious reference to his Japanese heritage, early training in Japanese painting affected his way of seeing in subtle ways.

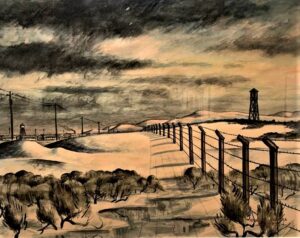

But suddenly it came to an end when on February 19, 1942, U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the infamous executive order 9066 authorizing the relocation of all persons considered a threat to national defense from the west coast of the United States inland.

The order fell like an ax on the lives of people of Japanese descent regardless of whether or not they were citizens.

This February is the 80th anniversary of that order.

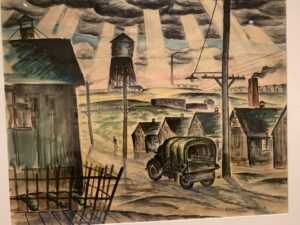

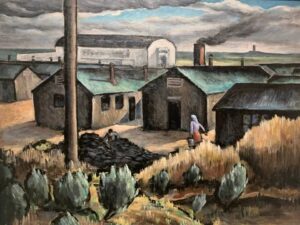

Nomura and his family were forcibly incarcerated along with 120,000 other people of Japanese ancestry. They first went to the State Fair Grounds in Puyallup,

then to Minidoka, in desolate Hunt, Idaho.

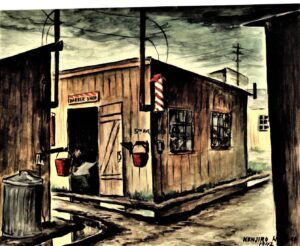

But Nomura never stopped painting! He made over 100 watercolors of the buildings, the people, and the natural environment in the camps. They remained rolled up in a closet until the 1990s.

Nomura’s son, George, brought work out of storage about 1990. It was shown at the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle in 1991 and toured for twenty years. Curator David Martin carefully chose twenty of them for this exhibition and orchestrated their donation to the Tacoma Art Museum.

After years of internment, Nomura returned to Seattle. He then confronted severe personal challenges, most tragic of which was his wife committing suicide.

But with the encouragement of friends and probably also his second wife, he began painting again His work transformed completely, perhaps not surprisingly after so many traumas, into dynamic abstractions that he created up until his early death in 1956.In this too, he demonstrated a completely original approach.

Folk Dance 1950 collection of Michael and Danielle Mroczek

Shopping Center 1950 Collection of Lindsey and Carolyn Echelbarger, promised gift to Cascadia Art Museum

All images from the incarceration on in the collection of the Tacoma Art Museum.

This entry was posted on February 1, 2022 and is filed under American Art, art criticism, Uncategorized.