A Visit to South Africa by Pamela Allara and the new opera Sibyl by William Kentridge

Professor Kim Berman and Pontsho Sikhosansa work on a Ramarutha Makoba print in the Newtown studios. Photo supplied

Some background information: in the 1980s, when I taught modern art history at Tufts, I was the academic advisor for the students in the MFA program at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. One of my students, Kim Berman, was from Johannesburg and she was very active in the anti-apartheid movement. Through her, I became interested in activist art, and contemporary South African art in general,

In 2000 I was appointed to teach at the Johannesburg Technikon. I have returned every year since for research, writing, and curating. Obviously, no trip was possible last year, so I was especially excited to travel again, for two weeks this past April.

Susan has asked me to discuss my visit to William Kentridge’s studio, which took place right before I left, but I cannot resist briefly showing a few other highlights. One was an exhibition at the Goodman Gallery of the wire sculpture of Walter Oltmann, “Armour and Lace: A Bestiary”. In the photo above , Walter is on the right; David Paton, Kim’s colleague at University of Johannesburg on the left; I’m in the center.

Walter taught for many years at Pretoria University, and has recently retired early. Retirement is encouraged by age 65, as the South African government is eager to make way for non-white faculty.

Back in 2003, I included one of his life-sized standing armored figures in the Co-existence exhibition I curated at Brandeis’ Rose Art Museum). He is still working with those figures, although as the title suggests, he has also turned to wire lizards and other flora and fauna in wire reliefs. As always, the sheer volume of the labor involved was mind-blowing

I also visited Usha Seejarim’s studio on the other side of Johannesburg. Her studio does not seem spacious, but perhaps that is because her work is large. A line of red and yellow threads spread about 20 feet across the floor, which will be installed in the arts festival in Grahamstown, South Africa in June. Lying on the floor next to the thread piece were charming ‘spiders’ made from one iron plate with thin metal legs attached.

She is also constructing, with the help of one of her assistants, 8 metal models of the clothes peg, each about a foot high, that will be sold to cover the costs of fabrication and shipping of “The Resurrection of the Clothes Peg”, which will be the centerpiece of the Burning Man Festival in Nevada in July.

Her work draws from domestic objects like irons and clothes pegs . As she explained in a conversation with Robert Preece in Sculpture magazine

” The domestic objects in my work are, for me, somewhat metaphorical; I think about their function. For example, the clothes iron smooths out creases; its function is to make a shirt or other item of clothing neat and presentable. The clothes peg holds, clasps, grips, and embraces; the broom sweeps away dirt and clears a space. I am aware of how these objects and their use are associated with a female role. Thus, they become quite genderized. I have come to recognize the particular triangular shape of the iron and how that shape has a feminist/vaginal reference. So, the works do not refer to a specific context as much as they refer to the notion of domestic roles and how they are—historically, culturally, socially—assigned to or claimed by the female. I would like to think of these forms as universal symbols understood around the world.”

Usha was just back from Lagos, where the work is being fabricated. The final work will be about 40 feet high, and the most monumental piece at BM. She is now trying desperately to get a visa so she can be there for the opening.

Now on to the visit to William Kentridge’s studio. Kentridge is, of course, South Africa’s most well-known artist; recently, he has received The Queen Sonja Lifetime Achievement Award from the Queen Sonja Art Foundation in Norway. Kentridge also is a long-time friend of Kim Berman.

After her MFA studies in Boston, Berman founded the community printmaking studio, Artist Proof Studio, in Johannesburg in 1991. It is now a thriving center, offering classes in printmaking and professional printing services to artists such as Bokang Mankoe.

APS had been downtown, but the city wanted its convenient location for its offices, so moved it lock, stock and barrel to a fancy shopping center. So the students must take a daily hike from the public transport downtown. Because it was a holiday, only two of the printers were there when I arrived.

Kim and Nathi Ndladla, the head of the studio, were working on the giant Kentridge print, “You Who Never Arrived,” with its forest of trees. The work consists of about 12 prints attached to handmade paper that is then affixed to cloth, becoming a sort of tapestry. I was nervous about the two of them filling in the blanks across the spaces between the individual prints and touching up the trees with black ink, but Nathi and Kim clearly enjoyed themselves.

The next day Nathi, who had the Kentridge hangings carefully wrapped, drove me to William Kentridge’s house in the suburb of Houghton so he could sign them. I was sure that the source of his imagery was one of the trees on his property, but when I looked around I was clearly wrong.

William’s son had been married there in the garden the day before, and clean up was taking place. William was leaving for exhibits in London and Lucerne that evening, but took the time to show us the new video that will accompany a performance of Shostakovich’s 10th Symphony by the London Symphony Orchestra (I think).

He also showed me the notebook where he jots down the quotes and phrases he uses in his artworks. He was remarkably gracious, given his tight schedule, but this is true of South Africans in general. Also remarkable is the lack of ‘artistic ego.’ After all, he is South Africa’s most well-known artist, with a huge retrospective planned in London next year. But clearly, he considered Kim and Nathi to be colleagues. I may be wrong, but I think many successful American artists would consider their assistants to be just that: assistants. Not the case here, another reason why I enjoy going to South Africa and writing about the art there.

The political situation in South Africa is not the greatest at present, as Cyril Ramaphosa’s government is rife with corruption. The situation is also dire with museums; for example, the Johannesburg Art Gallery’s facilities are in terrible shape, with the collection in jeopardy. And yet, artists continue on, and good work continues to be made. Their continuing productivity is a source of hope in grim times.

Kentridge lives in the house he grew up in. His father, Sir Sidney Kentridge, defended Nelson Mandela in the Treason Trials that sent Mandela to prison for 27 yrs. His studio is the former garage on the property, now quite transformed! The collage of flowers and plants on the end wall of the studio he made for his daughter’s wedding a year ago, and re-installed for his son’s wedding, which had taken place the day before we arrived.

____

Afterword by Susan

I was very fortunate to see the London premier of William Kentridge’s opera Sibyl at the Barbican.

The artist himself was there in the audience!

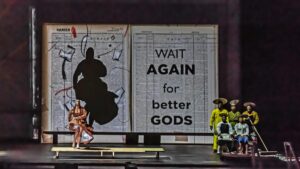

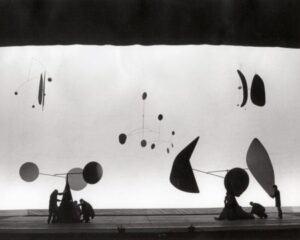

Here is the only photo I was permitted to take of the theater screen before it began

Here is great clip

From The Times Review Donald Hutera

Monday April 25 2022, 12.00pm, The Times

“The South African visual artist William Kentridge’s Sibyl is an extraordinary achievement, no matter how you categorise it. The work comes in two parts: an approximately 20-minute film accompanied by live piano and male chorus and, at double that length, a ritualistic chamber opera (originally commissioned by Teatro dell’Opera di Roma and created between 2016 and 2019) featuring more music, song and dance and the kind of multilayered stage imagery in which Kentridge specialises. To call it stimulating would be an understatement. It is also cumulatively, and sometimes almost inexplicably, moving.”

Here is a You Tube clip

It was a multimedia extravaganza of music, dance, costume, all performed by South Africans of incredible skill.

The theme was the unpredictability of trying to predict the future. The Cumaen Sibyl was a fortune teller who threw fortunes out at random on oak leaves and people had to figure out which was theirs, a metaphor for the unpredictablity of life and knowing the future. So the opera had a lot of paper flying around, lots of fortunes.

But it also refers to our contemporary efforts to predict the future with algorithms

As one anonymous analysis explained

“Unspoken throughout but hovering over the opera is the notion that our contemporary Sibyl is the algorithm that will predict our future, our health, whether we’ll get a bank loan, whether we’ll live to 80, what our genetics will be. This certainty of an implacable mechanism that determines our outcome is juxtaposed against the desire for a more human connection to our destiny, an instinct to believe in the possibility of something other than the machine to guide us in how we see our future. The work is a profound, jarring, playful, and visually stunning meditation on what it means to be alive in our current moment in history, grappling afresh with humanity’s primordial task of making sense of the inherently tragic state of always knowing, yet never knowing, where our end will lead us; the cursed and blessed consciousness that makes us human.”

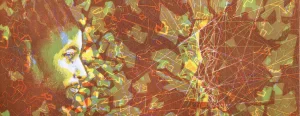

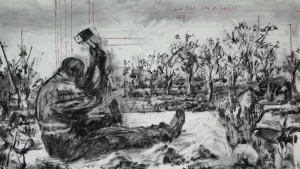

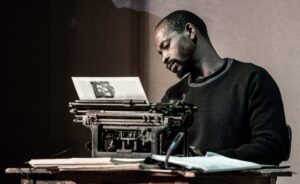

The evening began with a 22 minute silent black and white film The City Deep with choral director and dancer Nhlanhla Mahlangu leading a chorus of nine performers and and Kyle Shepherd, a leading progressive piano player from South Africa. Above is a still from a the Kentridge film, The City Deep

As explained by the Goodman Gallery in NYC ( where you can see drawings for the film)

“In City Deep, the artist’s unique charcoal animation technique of successive erasure and redrawing conjures a non-linear story featuring his drawn alter ego Soho Eckstein, set between a municipal art museum (based on the Johannesburg Art Gallery) and an abandoned mining area at the edges of the city where unofficial artisanal gold mining takes place.

” The action jumps: the museum collapses, Soho comes face to face with his fate, whilst a solitary miner persistently works against his destiny. Interspersed throughout are images of the film’s creation, of the artist in his studio—always itself an action (a futile one) against destiny.”

” City Deep is the anticipated 11th film in Kentridge’s Drawings for Projection series, a collection of animated films drawn over 30 years, featuring the protagonist Soho Eckstein. South Africa’s political transition from the violent years of apartheid to democracy sets the scene for a saga of loss, love, anger, compassion, guilt and forgiveness. The films revolve around the power-hungry mining magnate Soho Eckstein, his wife Mrs. Eckstein and her lover, the solitary artist Felix Teitlebaum. As the story unfolds, Soho’s empire crumbles as he comes to terms with his own frailties and the first signs of mortality.

” Like previous films in the series, City Deep is grounded within Kentridge’s home city of Johannesburg and can be viewed as a counterpoint to the 1990 film, Mine, which depicts images of the deep level mining industry.

City Deep extends this depiction to the informal, surface-level “zama zama” miners of current day Johannesburg. Translated from Zulu as ‘try your luck’ or ‘take a chance’, “zama zama” is the name given to the miners who illegally work decommissioned mines on the edges of the formal mining economy. Manual labour replaces large machines, creating open scars in the Highveld landscape.

In City Deep, the “zama zama” miners and the landscape merge into artworks hanging in the Johannesburg Art Gallery, itself built during the heyday of gold mining in Johannesburg. Wandering the exhibition spaces is a deeply contemplative Soho gazing at the artworks and into vitrines. Towards the end of the film the gallery collapses in on itself, an imagined demise of an institution in a state of increasing dereliction.

The second part of the evening featured Waiting for the Sibyl, the opera. During the pandemic Kentridge published the libretto.

As Kentridge explains:

“The project at Rome Opera, Waiting for the Sibyl, comes from an invitation from the opera house to make a companion piece to the 1968 piece by the American artist Alexander Calder, called Work in Progress. The 1968 piece is a beautiful, whimsical almost-happening of the era, with mobiles slowly turning on the stage, and groups of bicycle riders; but the signature mobiles of Alexander Calder are the heart of the piece.

In responding to the invitation to do a second half of the evening, I wanted something that also had a sense of turning, of revolution, and of the lightness of the Calder. I was reminded of the image of the Cumaean Sibyl. My understanding of her story was that she lived in her cave near Naples; people would come to her with questions about their fate, and she would write the answers on oak leaves. There would be a pile of oak leaves at the front of her cave and people would come to get their answers.

But inevitably there would be a wind which blew the leaves around – so you never knew if you were getting your fate or somebody else’s fate. It’s a beautiful metaphor of not being able to predict our futures. This idea of leaves blowing and turning, and uncertainty, became the connecting point for Calder’s moving, turning mobiles and something that grounds the piece with that turning but hooks into questions that I’m interested in today.”

Photo by Yasuko Kagayama

“I was thinking about the theme of fate and our future and the telling of our future, as the Sibyls did; this meets the work of Alexander Calder; and both of these come together in the material ways of working to make the piece.

photo Stella Oliver

The idea of turning leaves into pages, and the pages swirling around, brought together the turning sculptures of Calder, and the pages on which I had been obsessively drawing in the service of making films out of books. Part of the form became the projections of the texts and the drawings in the book and the shadow made in the book by the performer of the Sibyl. Different scenes were added. A scene in the waiting room for the Sibyl. A scene about which is the right decision and which is the wrong one. How do you know which is the chair that will collapse when you sit on it and which is the chair that will support you?”

There were a lot of people sitting on collapsing chairs in the opera. The multimedia made it overwhelming, stunning piano, singing, film, dance, costumes. The odd flat discs on people’s heads I finally figured out connected to the Alexander Calder

Here is another excellent You Tube video from the rehearsal for the original performance in Teatro dell’Opera Rome, September 2019, before the pandemic delayed it.

Even in the stills you can see the layers of complexity!

Photos by Stella Oliver and Yasuko Kasegama

This entry was posted on June 14, 2022 and is filed under Uncategorized.