Humaira Abid: Confronting Women’s Oppressions

Women’s rights are front and center as Iran erupts in anger at its oppressive extremely conservative government after Mahsa Amini a young woman died from being beaten by the so-called morality police. Two 16 year old girls Sarina Esmailzadeh and Nika Shakrami, have also died in the protests.

In this country, the repeal of Roe v Wade led directly to ongoing protests all over the country. More efforts to govern our bodies.

Women’s rights have never been more on our minds.

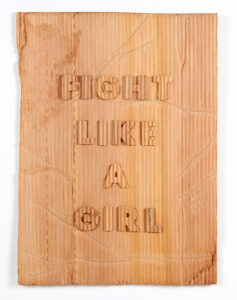

Pakistani-born artist Humaira Abid created all of the work in “Fight like a Girl,” her most recent Seattle exhibition at Greg Kucera Gallery, before the current protests. But throughout her career she has taken a stand to speak out about issues pertaining to women that are rarely discussed.

Abid points out that the term “Fight Like a Girl” has been used to denigrate girls, suggesting that they don’t fight as well as boys, but her point of view is that girls are strong, determined, and fight for everything they get.

In Iran women by the thousands are leading the nation-wide protests, and they persist in the defiance of widespread violence against them by the government.

Iran, as Resa Aslan points out in his essay “From Here to Mullahcracy” has a democratic constitution that clerics discarded: “what had begun as a vibrant experiment in Islamic democracy…” turned into a “state ruled by an inept clerical oligarchy with absolute religious power.” Iran is not a theocracy, Aslan explains, because of that constitution which “enshrined fundamental freedoms of speech, religion, education , and peaceful assembly.“

It is those discarded rights that the people of Iran, both men and women, are demanding.

Humaira Abid’s trajectory through art schools in Lahore included overcoming a lot of sexism. She studied two completely different techniques, woodworking and miniature painting. The teachers would not let her study woodworking or sculpture in art school, it was believed that only men could make sculpture, so she went to traditional wood carvers to learn.

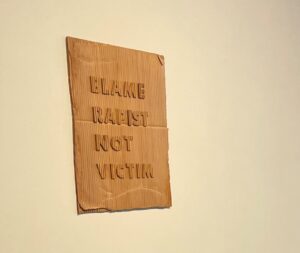

Along the first wall of Abid’s exhibition are protest posters rendered on meticulously carved pine that replicate the cardboard of protest signs. Carved on each one is a protest: “Blame Rapist not Victim,” “Enough,” “Tolerating Racism is Racism.”

Abid first seduces us with aesthetics and beauty, then gives us a punch in the face with specific imagery that speaks to the “issues people are afraid to talk about” in women’s lives both with respect to Islam and with respect to the concerns facing all women.

This exhibition includes works that address incestuous rape, miscarriages, breast feeding, and the fate of migrant women and children.

“Woman with a Breast Pump” outrageously connects the breast pump with the faucets for ablutions outside of mosques, in a tondo shape (as in a Renaissance Mother and Child): she surrounds a detailed painting of a breastfeeding mother (based on a photograph) with a halo of faucets in gilded wood.

In the series “Tempting Eyes” woman’s eyes look assertively from various Islamic head coverings on rearview mirrors (simulated in wood): the works comment on the driving ban for women in Saudi Arabia (lifted in 2017, but with other severe restrictions on women still in place). The law stands that declares that the eyes alone are dangerous and can violate the law with too much makeup. But these eyes defiantly stare right at us.

In “Woman in Black,” 2022, a small oval miniature painting of a woman covered in black holds a white rose. The stem of the white rose connects to a long chain (carved in wood) leading to a child’s head lying on the floor with a black bird sitting on it. In some ways this is the most frightening image in the exhibition: the long chain both restrains the woman and suggests an umbilical cord leading to the baby. The black bird suggest death. With the repeal of Roe v Wade the possibility of death from miscarriages has escalated.

Abid has long addressed refugees and migration, particularly the suffering of women and children, who experience rape and kidnapping. Here are images from her exhibition “Taboo” at the Bellevue Art Museum in 2017-2018

Borders and Boundaries includes a barbed wire fence entirely carved from wood. But the main point is that it makes reference to refugee camps. It is a poignant with the underpants stained red hanging on the fence. That red stain is precisely Humaira’s point about topics that are taboo, such as women menstruating while they are in the desperate straits of fleeing or in a refugee camp.

Fragments of Home Left Behind 2017 includes portraits of real refugees based on photographs

Left Laiba Age 6 Afghanistan photograph by Muhammad Muheisen Right Mona Age 5 Hassakeh, Syria photograph by Muhammad Muheisen

Sofia Hassan Mahmood and Isaac Mahmood, Ages unknown, Somalia photograph by Fazal Sheikh

The World is NOT perfect

In this pile of wooden blocks you see many different shoes each one suggesting a different identity, they refer to as the artist explained “gender, age, and culture, but also resonate on a universal level.’

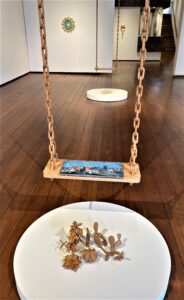

That theme appears in three swings titled “This world is beautiful and dangerous Too.” On the seat is a miniature painting of a child happily swinging in what appears to be a fantasy land. But underneath threatening looking cactus grow. Abid explained that this series began when the Taliban killed 140 children in a slaughter in 2014 in Peshawar, Pakistan.

Humaira also pursues the theme of RED in many works that are bravely confrontational ( she had an entire exhibition with that title at Art Exchange Gallery who championed her work in 2011 when she was just beginning in Seattle.

The Stains are Forever

Aspect of Motherhood

All We Need is One Fertile Egg

Art Exchange also held a show called “Istri” , a long series of works with wooden irons and miniature paintings layering comments on violence and women. In Hindi “Istri means wife and woman

and the same word means “iron” in Pakistan.

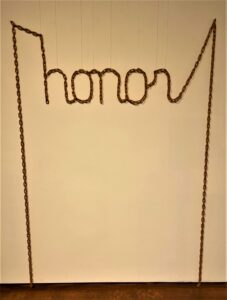

Finally “Honor’” written in carved wood chains says it all: the prison, the misuse of language, the oppression all in the name of ‘Honor.”

Abid’s beautifully crafted wood sculptures with their direct messages have never been more timely.

I wanted to add a brief note about a book I just finished reading called Women, Art and Literature in the Iranian Diaspora. While the author, Mehraneh Ebrahimi is writing about Shirin Neshat and the graphic novel Persepolis, among other books, her point also applies to Humaira’s work. She speaks of ethics, aesthetics and politics as way to humanize the Other. That is exactly what Humaira does, she is humanizing both the Other of Islamic women, as well as women in general. That is the importance of her work. The other point Ebrahami makes is the privilege of ex patriot women in their freedom to address the condition of women.

This entry was posted on October 17, 2022 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, Feminism, Iran, Iranian protests, Iranian Women, Uncategorized.