At the Tate Modern Part II Maria Bartuszová and Magdalena Abacanowicz

I just read an editorial by Eddie Chambers in the Art Journal, that women artists are still being slighted in the art world and by art historians. Price wise their art has much less value and they are not given the same attention in museums because, Chambers declares that curators say they are “in hock” to commercially successful contemporary artists.

Hopefully that is changing. I saw this book The History of Art Without Men, for sale at the National Gallery, London, when I went there to see the amazing Nalini Malani exhibition ( more on that soon), and at the Tate Modern there were three major exhibitions of work by women.

The first is Cecilia Vicuna, just discussed above.

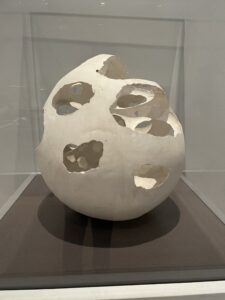

The work of the second artist Maria Bartuszová. (1936 – 1996)

you see at the top of this review.

A sculptor from Slovakia,

first a Communist country, then a former Communist country ( a monumental fact that is oddly omitted from her biography- as is much else) she was not seen in exhibitions outside her country during her lifetime.

Bartuszova’s exhibition is part of an initiative at the Tate Modern that includes Cecilia Vicuna and Magdalena Abakanowicz, presenting women artists who have revolutionised modern sculpture. All three of these artists are from outside the “Western” world, Communist Czechoslavakia-Slovakia, Peru – indigenous, and Poland also Communist.

Bartuszová is the least well known of the three artists. She was able to support herself under Communism with public commissions. But her public work was not ideological, but abstract.

She learned about mainstream art from books while she was living in Košice the second largest city in Slovakia, deep in central Europe not far from the border of Ukraine and Hungary. She moved there from Prague and its exciting intellectual community lured by possibilities of public art commissions in a rapidly expanding city, and inexpensive housing.

As she was raising her small children she had the idea of casting plaster over balloons., often submerging the forms in water in a technique she called “gravistiumlated shaping” as th weight of the plaster determined the shape of the sculpture.

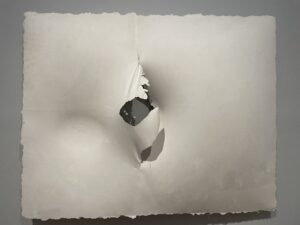

From there she began to blow into the balloons and poured plaster over them , she called it ‘pneumatic casting’ the result was a fragility that evokes eggs or shells.

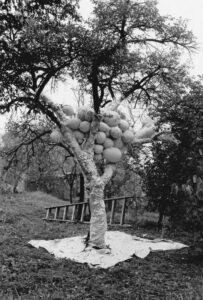

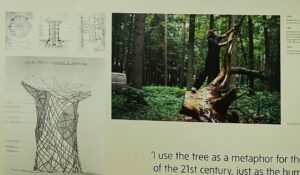

She also created temporary works in nature and later in her life hung her work in trees.

She also created temporary works in nature and later in her life hung her work in trees.

The playful quality of the work pairs with an intense feeling for nature and original forms that create a lyrical presence. She was familiar with Luca Fontana and Brancusi, and we see that in these works.

So we can place her in the cerebral, sensual category of contemporary sculpture, courting the line between abstraction and naturalism.

Magdalena Abakanowicz “Every Tangle of Thread and Rope”

While Maria Bartuszová creates fragile intimate works, Magdalena Abacanowicz creates large muscular pieces made from sisal as well as horsehair and hemp. The works called “abacans” to indicate her originality (named after her) moved in her early career from the wall

to the middle of the gallery, taking on a creature like presence. As we walk among them we feel the innate energies of nature. in this one we see a fibrous connection between two lung like shapes.

Abacanowica was born in 1930 to Tartar Russian Polish nobility, at the beginning of the war they retreated deep into the forest, then they lost everything. that experience in the forest deeply marked the artist, and she feels strongly the power of the forest.

In her late work she turned to trees themselves

“Arboreals symbolise our concern with nature, which neglected and abused by man, now turns against him with vengeance. They remind us that a tree is our friend; it gives shade and oxygen, bears fruit, shelters birds and animals and makes climate hospitable to all ”

“I use the tree as a metaphor for the ecological architecture of the 21st century, just as the human body served as a metaphor for the shape of a Romanesque cathedral. ”

Both of these artists are immersed in nature, and concern for its future. Both grew up under Communism, but supported themselves as artists. Abacanowicz gained great esteem while Maria Bartuszova was unknown. I am thankful they are side by side now at the Tate, as it gives us in both cases a highly original approach to sculpture using organic materials.

This entry was posted on May 21, 2023 and is filed under Contemporary Sculpture by Women, ecology, Uncategorized.