Henry Taylor, Ruth Asawa, Kay Walkingstick

Henry Taylor 8th floor roof of Whitney Museum of Art, November 2023, Untitled, bronze, 2020

Henry Taylor 8th floor roof of Whitney Museum of Art, November 2023, Untitled, bronze, 2020

In early November on a trip to NYC, I saw exhibitions by Henry Taylor, Ruth Asawa ( Whitney Museum) and Kay Walkingstick (New York Historical Society): it was wonderful to see the work of major artists in major venues in NYC that are not part of the old fashioined mainstream white guy art history. Each of these artists is now well-known, each has gone entirely in their own chosen direction.

What a change from not too long ago when the big issues were whether art could be political and whether non abstract art was legitimate. But during my career this change has taken place. When I first started writing in the 1970s and 1980s, the farthest from mainstream were the earthworks artists, giant works in the wilderness created by bulldozing. Although they were full of metaphors, ( as in Smithson’s Spiral Jetty) any realism in a painting at that time was still considered a failure of nerve.

Now we have a wide range of possibilities and no one dictating what artists need to do to be creating meaningful art. Admittedly many artists still go after “success” and the latest thing, but many are freed from that to create as they wish. The result is artists like

Henry Taylor, Ruth Asawa, and Kay Walkingstick.

Warning shots not required, 2011 Acrylic, charcoal, and collage on canvas 75 1/4 × 262 1/4 in. (191.1 × 666.1 cm) The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; purchase with funds provided by the Acquisition and Collection Committee

Henry Taylor is from Los Angeles. As a contemporary art critic, I am not familiar with him!. Apparently he had his first solo exhibition about two years ago,in his sixties, and here he is at the Whitney Museum, with a huge exhibition “Henry Taylor: B Side”this is an ironic title, suggesting these are the pieces that are on the “other” side of the record, or in other words, less known. But the exhibiiton is a thorough overview of the artists work. Intriguingly I just discovered that one of the works considered his “masterpiece” by some, was omitted – his transformation of the Demoiselles D’Avignon called From Congo to the Capitol and Black Again.

I think omitting it was a good idea, when all of his paintings here are so sympathetic to the subject (usually families and friends), and personal. We don’t need Picasso to legitimize Henry Taylor.

Eldridge Cleaver, 2007 Acrylic on canvas 75 3/4 × 94 3/4 in. (192.4 × 240.7 cm) Private collection

Henry Taylor, That Was Then, 2013. Acrylic on canvas, 95 × 75 in. (241.3 × 190.5 cm). Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; The Henry L. Hillman Fund 2013.12. © Henry Taylor. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photograph by Sam Kahn

Here are two examples of his portraiture the homage to Eldridge Cleaver, above, and the ironic That was Then, below.

Both are painted in flat areas of similar color. Cleaver obviously reminds us of Whistler’s Mother, which is really funny.

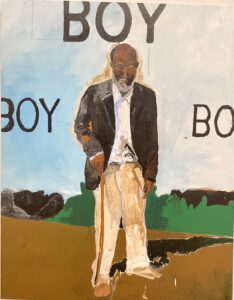

That was then shows an old man with “Boy” written on three sides. It is poignant and perhaps sarcastic. Are black men no longer called boys. I hope so. The image tells us that this elderly man certainly was. Taylor’s portraits are full of empathy for the sitter, as we see here.Carefully observed details of the man’s clothing tell us a lot about him

Here are the Obamas (2020)

and David Hammons selling snowballs in Africa. (2016) based on a performance Hammons did in NYC. Note the subtle references to Christmas

i’m yours” (2015)

I’m yours provides three generations of a family, each with a different expression, but all engaging the artist directly: one is resigned, one is angry and one is questioning.

Resting is a portrait of some of his familly, and their informal engagement with the artist suggests a relaxation, but behind them a third figure lies, is he sleeping, is he dead? We don’t know.

Resting 2011

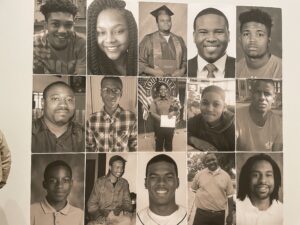

“the times thay aint a changing, fast enough!” (2017), (Philandro Castile)

There is a shock in this painting, as we look at the wide flat areas of paint that send our eyes to Philandro, then we see the gun.

One of the show stopping installations was an homage to the Black Panthers. We could really experience their potency as we interacted with the mass of manniquins in leather jackets and the photographs of Panthers.

Untitled, 2022 Black Panthers Mannequins, leather jackets, and posters Dimensions variable Collection of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

.

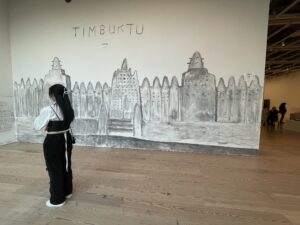

Another powerful experience is the improvisational drawing in the so-called window lounge. Roberta Smith described it well:

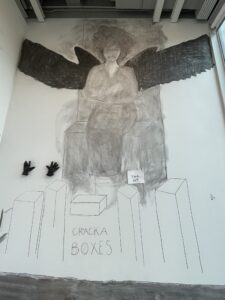

“Using an image of Djenné’s Great Mosque, it loosely delineates the forced journey of many Africans from their homeland to a Southern plantation. Then comes the Great Migration that began after World War I. Passing reference is made (in an alluring little landscape) to “Big Momma’s House” in Naples, Texas, from which Taylor’s parents migrated to Oxnard, Calif., in the 1950s. The finale is Chicago and Whitney Houston as a large presiding angel. Here, dashed-off, stream-of-consciousness is perfect. It’s part of a history that all Americans should know by heart.” (NYT, October 18)

detail Whitney Houston

In one gallery we see this strange tree. What is it about? Trees always lead to thinking about lynching, but here the tree is completely without branches. It has an ominous presence that can suggest a guardian, or a disguise, or a place of confinement.

Most of the exhibition consists of portraits of his friends and family, created with empathy. He captures an everyday event and suggests its ordinariness as well as its grandeur.

the dress, ain’t me, 2011 Acrylic on canvas 84 1/4 × 72 in. (214 × 182.9 cm) Private collection; courtesy Irena Hochman Fine Art Ltd.

Taylor gives us intimacy. His parents migrated from East Texas to Southern California during the Black Migration of World War II, Taylor grew up in Los Angeles. When he went to art school he worked at Camarillo State Mental Hospital, from 1984 to 1995, making portraits of the people he met. 19 of those portraits are included here, suggesting his empathy for the patients.

“Henry Taylor: B Side” includes sports stars and political stars as well as ordinary people. But the stars look approachable and the ordinary people look like stars.

Untitled, (Obamas) 2020

Also at the Whitney is “Ruth Asawa:Through Line”

Ruth Asawa as a Japanese American was interned during World War II, but she had the incredible luck to be with artists that taught her a great deal—- specifically animators from the Walt Disney Studios, who taught art in Rohwer Relocation Center in the Southeast corner of Arkansas. She was fortunate also in being allowed to leave to go to school. In 1946 she attended the avant-garde Black Mountain College

At that time she began creating what became her famous looped wire sculptures, a technique she learned in Mexico. Here we see one example of her sculpture from the Whitney Museum exhibit “Ruth Asawa Through Line”. This piece has a long title:

Hanging Six-Lobed, Complex Interlocking

Continuous Form within a Form with Two

Interior Spheres, 1955 (refabricated

1957–58). Brass and steel wire

The main theme of the exhibition is her extraordinay drawings, using line. Of course the sculpture above also consists of line, but as we experience her varied media and line, it enriches our understanding of her sculpture as well. Here are two unusual pieces.

Untitled (S.003, Freestanding Reversible Undulating Form), 1998 Bronze Private collection

Untitled (SD.254, Tied-Wire Sculpture Drawing with Six Petals in Center), c. late 1960s Tin 32 ¾ x 32 ¾ x ¼ in. (83.2 x 83.2 x 0.6 cm) Private collection

The exhibition is full of notebook sketches that reveal her deep exploration of growing patterns in nature, such as we see here executed in tin.

We feel a whole new insight into line as she creates in so many different materials.

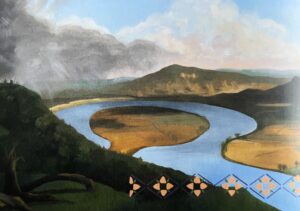

At the New York Historical Society Kay Walkingstick Hudson River School created a thrilling series of paintings overlaying historical American landscape paintings with native signs, reoccupying the land

What we see are brilliant paintings of landscape and seascape and in the foreground are emblems of native tribes as though protecting the land.

Aquidneck after the Storm 2022 oil on panel in two parts, Colleection of Charlotte and Herbert S. Wagner III

Wampanoag Coast, Variation II, 2018 oil on panel Collection of Agnes Hse, PhD and Oscar Tang

Thom Where are the Pocumtucks2020

As in Thomas Cole ‘s famous painting of t he Oxbow

You can see her overlay more clearly here

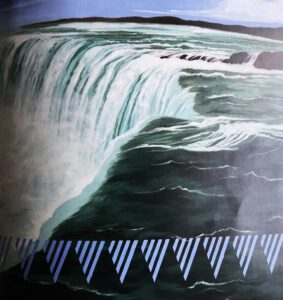

Niagara 2022

overlay with Haudenosaunee pattern

Farewell to the Smokies Trail of Tears 2007 oil paint on wood panel,Denver Art Museum

About this painting the artist wrote:

“Its about the traumatic experience of leaving home- leaving this beautiful home”.

From the catalog by Wendy Nalani E. Idemoto:

” the Cherokee painter felt the pull of her ancestral land the first time she drove through the present day Carolinas and tennessee. Ghostly silhuetts march across her seeking mountainscape, referencing the forced eviction of her people from their homelands in the 1830s along the Trail of Tears.

This entry was posted on January 7, 2024 and is filed under Uncategorized.