Our Blue Planet: Global Visions of Water

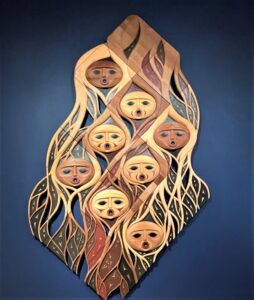

Canadian (Musqueam First Nation) Susan Point’s The First People suggests one theme of the amazing exhibition “Our Blue Planet:Global Visions of Water” at the Seattle Art Museum only until May 30.

Made of red and yellow cedar the piece seems to speak to us of both survival and sorrow, as these faces, each one distinctly different, call or perhaps sing to us with their rounded mouths as they float in interconnected streams.

The artist states:

“I am mostly inspired by nature and our connected human spirit. I try to illustrate our need to protect and restore our natural treasures and bring reflection and awareness to issues of concern in all our lives.”

“Our Blue Planet: Global Visions of Water” suggests that as it encompasses 92 works of art from 17 countries and seven native tribes.

During the pandemic three curators at the Seattle Art Museum assembled “Our Blue Planet: Global Visions of Water” with 74 artists from 17 countries and seven Native American tribes. It draws entirely from the museum’s permanent collection and loans from local collectors.

The curators, Pamela McClusky, Curator of African and Oceanic Art, Barbara Brotherton, Curator of Native American Art, and Natalia Di Pietrantonio, newly appointed Assistant Curator of South Asian Art, created ten themes that refer to water as necessary to life, as pleasure, as law, as mythic and as desecrated. They encompass celebration, poetry, ritual and catastrophe.

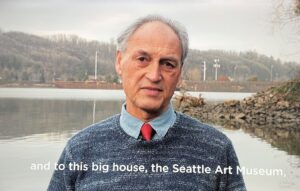

We are greeted at the entrance with a video of Ken Workman, a direct descendant of Chief Seattle, welcoming us, in the Lushootseed language.

It is moving and appropriate that he is standing on the shores of the Duwamish River as he greets us, the river of plenty before white colonizers arrived, and now a Superfund site and industrial wasteland.

Immediately after Workman’s greeting we look up to see Carolina Caycedo’s fifty-foot banner that charts the change in a river from healthy to polluted, signaling the theme of the exhibition in one dramatic statement. Caycedo considers rivers as living and spiritual.

Caycedo’s video “A Gente Rio: We River” 2016 brings us the voices of the people living on the Paranà River as they explain their traditional ways as well as the devastating impact of the Itaipu Dam on the border of Brazil and Paraguay, completed in 1984. But these people have also protested. They know exactly why the dam was built: the result of corporate impunity.

Nearby is a hammerhead shark, hung at our eye level so we can look right into the eyes of its hammer shaped head. The Ghost Net Collective on the Erub islands (Northeast of Australia) call attention to the lethal presence of the nets with these sculptures.

Here are the ten themes of the exhibition.

“Rains that Flood and Hypnotize”

“Rivers and Canoe Journeys That Sustain Life”

“Oceans with Bodies Like Our Own”

“Pools of Pleasure and Reverence”

“Patterns of Water”

“Future Waters Through the Eyes of Women and Children”

“Where Water is Law in Northern Australia”

“Sea Creatures that are Honored and Endangered”

“Tragic Memories of Global Trade”

“Mythic Vision form Water’s Creation to Regulation”

“Desecration of Our Troubled Waters.”

Speak them out loud and they form a poem to water and the ways it intersects our lives, present, past and future. I will touch on a few of them here.

“Rivers and Canoe Journeys That Sustain Life”

As we enter the next gallery, we are greeted by the regalia created by Danielle Morsette “Colors of the Salish Sea Ensemble” . It is to be worn for an honorary stop on a canoe journey.

Here in the Northwest we have joyfully welcomed the return of the canoe journey beginning in 1989 . Tribes travel the ancestral sea routes of their cultures to a host tribe. It has particularly revitalized the youth in many native cultures. Twice I have been lucky to be visiting a Native Community as it formally welcomed participants on the journey with music, dance, and shared food.

Three videos by Tracy Rector (Mixed race/Choctaw/Seminole) Managing Director of Storytelling, Nia Tero Foundation celebrate indigenous resilience and the beauty of the land, sea and sky, their music, their poetry, their regalia. The artist states:

“80% of all biodiversity is on Indigenous-held territories. The world is healthiest where Indigenous People are actively living, thriving and being ‘in community.’ This [stewardship] is essential in saving the health of our planet.”

“Rains that Flood and Hypnotize”

Rain is both a blessing and a threat. It sustains us and our food, but it can overwhelm us as we have seen increasingly often. In this section the images include a compelling photograph by Raghubir Singh of four women huddled together in a monsoon downpour, that particular type of rain in India that is welcomed, but also frightening. We see an image of flooded fields nearby by Raghu Rai After flash floods near Jaipur, as the label states “The water rapidly gathers in shapes like lightning across the ground and around stunted trees, devastating the environment.”

But another work from South Asia in the indigenous Mithila style by artist Amrita Das depicts the dramatic effects of the 2004 tsunami in Sri Lanka as people’s villages are wiped out entirely ( For a literary description of this same tsunami read Amitav Ghosh, “A Town by the Sea” in Incendiary Circumstances, 2006)

Patterns of Water

Claude Zervos gives us the Nooksack River in cathode ray tubes, suggesting its underground networks. Zervas has spent years next to this river and watched it degrade as it was dammed.

“Waves” by Ogata Korin a large Japanese screen evokes the rolling sea

“The Roar of the Sea” by Suzuki Masaya suggests the sound of the sea through an intense process of laquering mother of pearl.

“Oceans with Bodies Like Our Own”

Seeing global nomad artist Paulo Nazareth’s lying on a beach suggests the peace that we all experience, lulled by the sound of the sea. But he is only briefly resting on his year long journey walking barefoot from Brazil to New York.

“Pools of Pleasure and Reverence”

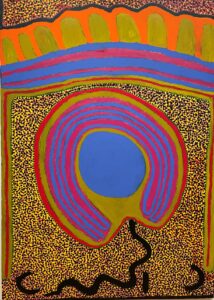

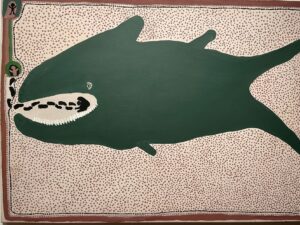

The dramatic image of Kurtal by Australian aboriginal artist Ngilpirr Spider Snell represents a spirit snake who “lives in a sacred waterhole called a jila. This desert spring is the only reliable source of water in all seasons . . . Kurtal is the moral protector of the right to use it and the land around it. …”

For a visit to Kurtal with Spider Snell, watch a trailer of Putuparri and the Rainmakers, by Nicole Ma

“Future Waters Through the Eyes of Women and Children” has some of the most provocative imagery in the exhibition. Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s video imagines a future world in which children collect the detritus of what we have left behind and create rituals with them. Here a child speaks to a head which becomes human, then a head again, and she takes it into the sea and burns it.

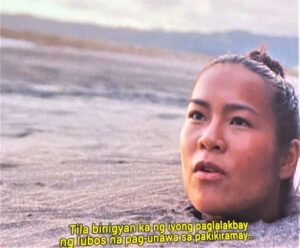

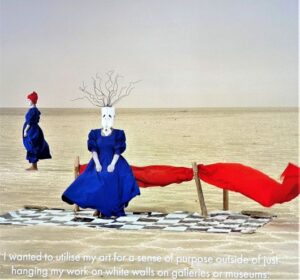

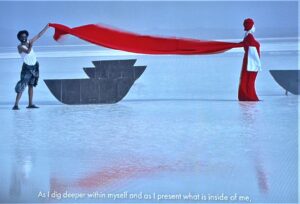

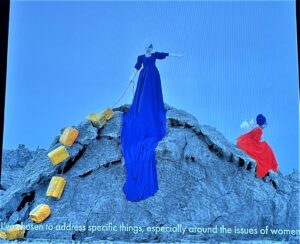

Also in this segment a still and a film by Ethiopian Aïda Muluneh, reenacts the process of getting water for survival in Dallol, northern Ethiopia, one of the hottest and driest places on Earth. Here is a view of it

As Muluneh explained:

“While travelling across Ethiopia for my work, I often encounter streams of women traveling on foot and carrying heavy burdens of water . . . women spend a great deal of time fetching water for the household.”

“Where Water is Law in Northern Australia” highlights four works on found aluminum by well known aboriginal artists, a dramatic departure from traditional eucalyptus, only seen here. The abstract patterns refer to law, ritual, ancestral power, clan designs, and, of course, the patterns of water.

“You are paper. We are sacred design. You make paper. Your wisdom is paper. Our intellect is sacred design, homeland, and ancestral knowledge of ancient origin. By painting these designs, we are telling you a story. From time immemorial we have painted just like you use a pencil to write with.” —Dula, Nurruwuthun (1936–2001), traditional leader of northeast Arnhem Land, 1999

Here you see Garrapara2018 by Gunybi Ganambarr,

Australian Aboriginal, Ngaymil clan, Northeast Arnhem Land. Ganambarr began painting after being told by an elder, “This is my wisdom. I’ll hand it over to you. Take it! Sit with us and live this life.” He says, “Soon I was learning the Yolngu side of deep significance… the foundations of the deep identity of the world.” The wavy designs refer to a specific bay and speak of clan affiliations.

Learn more here

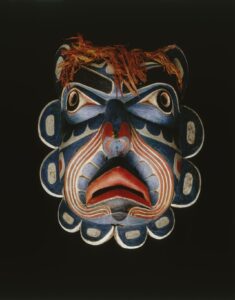

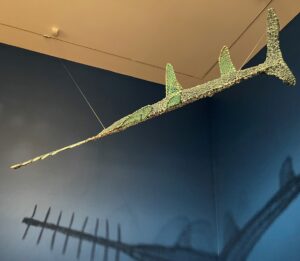

“Sea Creatures that are Honored and Endangered” The Mask of Ḱumugwe’(Chief of the Sea) from the Kwakwaka’waka rules over the water and this section that includes a sea turtle, a hammerhead shark (seen in the opening gallery), a sea bear and a sawfish. Both the shark and the saw fish are created in three dimensions from the fishing nets that are choking the sea.

Nearby is a bronze turtle called Dadu Minaral (turtle), 2007 by Dennis Nona from the Torres Straits (48000 kilometers, 1200 coral reefs at the northern end of the Great Barrier Reef, off the coast of Australia). Here the artist represents an historic initiation rite, by impaling the turtle on poles, but today the Torres Straits indigenous peoples are pioneering ecological partnerships to preserve this huge marine ecosystem.

I love this image of the whale fish vomiting Jonah by Jarinyanu David Downs

And here is the sawfish by Syd Bruce Short Joe . It is also endangered

The highlight of “Tragic Memories of Global Trade” is the reinstallation of Marita Dingus’s intense homage to the slave trade- 200 Women of Afrrican Descent and 400 Men of African Descent. The artist created each headless body over year and a half as a meditation on the atrocities of slavery. The work as been reinstalled to correspond to the diagram of The Brooks, a slave ship on the late 18th century.

Not far away is an installation by Claire Pardington of two elegant 18th century figures drinking tea surrounded by slaves and sailors. She suggests the different status with two techniques, Limoges and porcelain, as well as the cost in human lives for the tea trade and the thirst for Chinese ceramics.

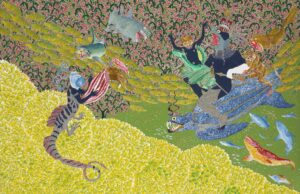

“Mythic Vision from Water’s Creation to Regulation” features Raqib Shaw’s The Garden of Earthly Delights V” showing an underwater world that is both beautiful and frightening in its fantasy and riff on Bosch’s famous painting. According to the curator “Beneath Shaw’s kitsch aesthetic lies his personal sorrow and his memories of fleeing Kashmir with his family. His idea of paradise is thus grounded in the physical and real space of Kashmir.”

“Desecration of Our Troubled Waters”

Among these works is a photograph by La Toya Ruby Frazier of the horribly polluted Braddock, Pa. where she grew up. Her Ted Talk talks about her work in Flint Michigan.

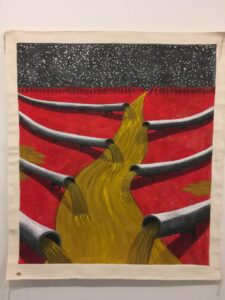

John Feodorov’s dramatic painting Desecration no. 2, represents pipe lines spilling pollution on native lands. Master Weaver Tyra Preston created special plain white Navaho rugs for the artist on which he painted, with some trepidation given the rugs’ powerful importance as metaphor of land and culture.

The exhibition includes so many more works that we see with new eyes from various parts of the museum. The rethinking of the idea of an exhibition brings together different cultural expressions to demonstrate that water is our shared concern, and necessary to our shared survival. In that way, the Indigenous voices are the most resonant in their respectful and deep understanding. But seeing their work and their voices placed among so many other cultures demonstrates the interconnectedness of everyone on the planet.

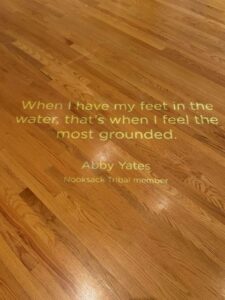

Finally, the curators reach out to our community:

“Our Blue Planet” is truly a groundbreaking exhibition.

This entry was posted on April 7, 2022 and is filed under Uncategorized.