Buster Simpson// Surveyor

Buster Simpson arrived in downtown Seattle in 1973 only four years after Lucy Lippard came here to create what is now known as the first ever exhibition of conceptual art. The catalog for that exhibition, a stack of index cards, is part of the Seattle Art Museum permanent collection. and on exhibit in Minimal Art and its Legacy, at the moment.

Conceptual artists opposed the marketing of art and the separation of art from life. That led them to explore ordinary life and materials as art; they also believed in calling attention to the abstract systems and structures of art.

(For a few more specifics see my blog on a recent show in Athens.)

Liberated by the open ended ideas of conceptual art, Simpson, in collaboration with other artists and community activists living downtown, began to intervene in the fabric of the city. The work of these early activists eventually transformed thinking in the city. Today we have urban gardens everywhere, we have a variety of trees, we have bus shelters with seats (sometimes), all of these were unknown in the Seattle of the early 1970s.

Simpson himself has gone from guerrilla street artist to highly respected participant in major projects: currently that project is the new waterfront that will emerge after the viaduct is gone (and the tunnel is completed, keep your fingers crossed that we SURVIVE that insanely gigantic drill going underneath Pioneer Square at this very moment).

Simpson’s major retrospective at the Frye Art Museum allows us to see some of the ephemera of his earliest street work, remakes of some pieces in museum scale and materials and new work following in the spirit of some of his primary preoccupations.

In 1969 Simpson was in Woodstock, Vermont creating what he calls on his resume“earthworks projects,” actually, as Jen Graves jauntily describes in her article, an improvised farm for people to visit as an alternative to music. But it got overrun by the masses and he had to become a security guard and then clean up after everyone. This experience was formative: he is still picking up junk and letting people mess with his art.

Simpson moved west in the early 1970s to be part of the founding of Pilchuk , then conceived of as an experimental multimedia retreat. He started living in downtown Seattle in 1973 , when it was grimy and gritty, impoverished and unassuming, when poor people (and he was one of them) were part of the fabric of the city. From his point of view as a public interventionist, he began to pioneer absurdly simple solutions to the complex issues of urban ecology, or in other words, how people and nature intersect with bureaucracies in a city.

He assumed a persona of “woodman” picking up cast off pieces of wood from the street (there is a great video of him impossibly loaded up and reaching for one more piece that he repeatedly drops). He worked with (and still works with) cast off detritus, recycled industrial materials, and found objects in the spirit of Marcel Duchamp, but approaches them with a sense of compassionate humor and practical purpose, rather than deadpan irony. We can compare it to Lawrence Weiner’s Declaration of Intent of 1969, ( see my blog above) in which he is trying to pick up driftwood. But Weiner didn’t do anything with it. It was the act itself that was his art. For Simpson there is always another step, a problem to solve.

Duchamp took a urinal and put it in an art exhibition. Simpson put a composting commode on the street for use in an area that had no public toilet. Furthermore, the toilet was going to provide fertilizer for an urban tree planted in the same spot. The difference is exact: in the first case a useful object was declared to be aesthetic, and consequently useless, in the second a basic need was met by creative thinking.

For Simpson, there has been no giving up, no sense of the futility of working with systems. He even included his videos of meetings in his retrospective, a wonderfully humorous nod to the hours he has spent in them.

He has worked inside and outside of systems (bureaurcratic, public art, political) throughout his career and pioneered with other artists in Seattle the idea of joining a design team for a major development at the beginning of the process, rather than as an art add on at the end. His ideas are often unrealized, altered, or reworked as a result of his interaction with systems. (This of course is the case with all public artists)

When a brilliant idea that he has developed carefully over months is dismissed entirely (as in Southeast False Creek Master Plan for Vancouver, BC’s Olympic Village) , he still sees it as a model of what might be possible.

He continues to pursue an idealistic, even utopian, practice, but a practice that is also humble: he begins with a problem at hand. But he brings to that problem a sense of poetry that transforms it into a work of art. He likes to call his process “poetic utility”. His work is never only an art object. It is placed within systems that shaped it, whether it is a city street, a salmon stream, a storm drain, or a crow’s nest.

Early on, he was hired at a minimum wage to clear a loft, he created an “exhibition” which he called “Selective Disposal Project” out of the dirt and rubbish (contrast to Duchamp’s “dust breeding experiment, in which he created an art work – The Large Glass- and allowed dust to accumulate on it for a year.)

Simpson suggested that the rubble from the freeway construction dumped on the waterfront would make a better park, working with youth corps and skilled craftspeople, than lots of clean and green.

He made a “crow’s nest” out of some rubble in a very old cherry tree about to be bulldozed, sat in it and then called on the city council to declare it in the public domain, by referring to the ‘legal rights of trees.’

Although the exhibition has a big emphasis on the remainders of these early works, tiny photographs, plans, super 8 videos, the artist has also created a number of sculpture specifically for the show, some of them recreations of earlier street art, some of them newly made full on art.

Some of these sculptural re creations are pedantic compared to their original playful sources, such as the man knocking beer bottles off of a table originally a peep show.

Another example of new work is Double Header Finial, a massive piece of gilded anodized aluminum, steel (found parts, finials and a Boeing nose cone), set on a triangular black flag. It is meant to provide ample perching places for crows, who are seen nearby in an old video competing for a perch on a flagpole, it is also a send up of the new Seattle, its gilded life style and ornate housing, why shouldn’t the crows join in. The black flag warns of the current risks of urban wealth.

Crow Bars with Electromagnet Bottles completely loses its original point and becomes a big sculpture: the original piece was a target for throwing beer bottles in an alley which then fell into a recycling bin.

One of Simpson’s constant themes though has been waterfront and water restoration. He has thrown limestone into polluted rivers, as a way of neutralizing acid, most famously in Hudson River Headwaters Purge, from 1990. The exhibition has a retrieved limestone disc from that project, a video of his original action, as well as its partner, “Projecting Limestone Purge, in which a naked Simpson slings limestones marked with “purge” at the World Trade Center as a protest against capitalism’s destruction of the environment.

We also have the recreated sling shot and rocks from that action. (These re creations are also Duchampian, he was always making replicas of his work)

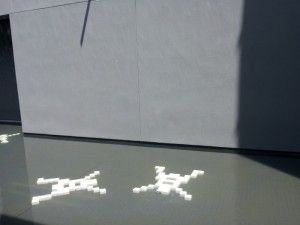

Sweetening the Pond , consisting of limestone squares forming frog like shapes in the Museum’s outside reflecting pool, refers to the same theme- that limestone neutralizes acid.

Habitat restoration of the waterfront is also referred to in Gabionne di Marble Venus, in the foyer of the museum, which creates a classical Venus figure from chicken wire filled with marble, planned as a way to prevent erosion in a city in Austria.

Secured Embrace icomprised of what Simpson calls a “breakwater armor unit” a tetrapod, “grasping” a tree root. The tetrapod becomes a heroic figure trying to prevent erosion, and the piece is a model for a means of both stopping erosion and encouraging healthy tidal life.

Simpson’s Tides Out/Tables Set also refers to pollution. It initially looks like a somewhat elegant table with interesting plates. Actually, he placed these unglazed plates into polluted streams and then baked them, so the “solid waste” became a brown glaze. We are eating off a glaze of our own pollution.

The exhibition includes some of Simpson’s “master plans” of which there are many: these plans basically follow the same simple principles of “poetic utility” but apply them to large scale projects, most notably the Brightwater Treatment System in Northern King County on which he worked for many years with Ellen Sollod, Jann Rosen-Queralt and Cath Brunner, Director of Public Art for King County. Collaboration is another major aspect of Simpson’s work that runs through his entire career, teamwork with artists, with urban homeless, with the general public.

In many ways, a museum exhibition of Buster Simpson is bound to stretch his principles in the wrong direction, toward objects, toward scale, toward permanence, and the efforts to do that in this exhibition are not successful. The difficulty of capturing the real principles of his art, ephemeral conditions, urban detritus, simple solutions to water pollution, is obvious. The museum could have made a messier show, Simpson did tear out a few pieces of the walls, in an effort to counter the formality and impersonality of the spaces, but in the end Simpson still belongs in the street working with cast off materials.

To see a little more of his early work go to “When Buster Lived Next Door,” at the Virginia Inn in Belltown, which has archival plans and photographs, and right outside the door are some surviving trees and benches and tree guards from the early nineties “First Avenue Project” and the “Urban Arboretum,”

Go to Post Alley and see the recreation of his “solar clothes line” ( note the oxymoron), one of those simple and obvious acts to meet a need, save energy and protest against condominium clothesline restrictions. ( see recent clothesline article in Seattle Times) .

In every respect, Simpson is hard to capture as an artist, his work transforms before our eyes from one object to another, from one idea to another, puns, metaphors are rife. Perhaps that is the main characteristic to take away from this Simpson moment in Seattle: disarming humor can win you a place at the table and then you can subversively introduce unacceptable ideas, somewhat like a court jester. Of course, Simpson is never really jesting, and today he is regarded as a major figure in ecological art.

This entry was posted on August 21, 2013 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art of Democracy, ecology, Uncategorized.