“Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art:” A Radical Proposal`

The first juxtaposition in the lecture by E. Carmen Ramos that introduced “Our America,” an exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, told the story she wanted to tell: the 1986 painting by Frank Romero of the police shooting of Rubén Salazar in 1970 next to “Washington Crossing the Delaware.” Two significant historical events of equal value. Washington Crossing we are all familiar with. The shooting of Ruben Salazar, the pioneering journalist, originally from Mexico, who worked for the Los Angeles Times for many years as an investigative journalist, is much less well known. Placing these two historical events side by side declares that our perspectives are still exclusive and limited, when it comes to American art and its partner, American history.

E. Carmen Ramos, Curator of Latino Art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, is building a new narrative for the history of American art. We are accustomed to the oft repeated lineage from colonial portraits to revolutionary history painting, to genre painting in the nineteenth century, still life, then in the twentieth century we have Alfred Stieglitz and modernism, the art of the New Deal, after World War II, Abstract Expressionism then Pop art, minimalism, feminism, conceptual art, postmodernism, and up to the present undefined history.

We know that in the 1960s and 1970s the Civil Rights movement and the Feminist movement sparked new narratives and new inclusions in that traditional trajectory. The Gay rights and AIDS added more dimensions. But today, we still don’t have an integrated history of American Art. We have mainly white men, with extras, a few woman, a few African Americans, a few gay artists.

Latinos sometimes get added in also, in the midst of the Civil Rights movement when the Chicano movement emerged full force.

But Ramos has another idea about the way to write an inclusive history of American art: Latino art is not an add on, it is embedded in all of the art that we have, all of the styles, directions, and politics.

By integrating Latino art into the mainstream, we get a different perspective. Ramos’s exhibition, “Our America” based on a selection of the permanent collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, emphasizes artists from Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba and the Dominican Republic. Artists from Central America, with one exception, are not included. Nor are artists who have come from Latin America. They will have to wait for the next installment.

This exhibition is a first step in the process of inclusion of Latino/a artists in the mainstream. It is going to travel all over the United States and hopefully change our conversation. Its timing is perfect. Just as our culture is demonizing immigrants forced to come here by our trade policies which are wiping out their living at home, we are offered these sophisticated works of art by immigrants, and descendants of immigrants, that declare that Latino/as are immeasurably enriching our country . As they assimilate US culture, they are also changing it, in exciting directions.

These art works address specific moments in Latino/a, US history or current conditions. They are all from the last half century.

Ramos has divided the exhibition into categories that underscore her purpose: Reframing Past and Present, Migrating Through History, Everyday People, We Interrupt this Message, Signs of the Popular, Turning Point, Street Life, Defying Categories.

In Reframing Past and Present she has included the most specific art about immigration and violent acts of racism

Delilah Montoya’s Human Water Station, can you see the plastic water bottle in the distance, on the path of people crossing the desert north of the border?

The tree photographed by Ken Gonzalez-Day could have been used for lynching. It is just one work from his project Searching for California Hang Trees. a groundbreaking book and photographic project on the lynching of Latinos in California in the 19th and early 20th century. In the book he describes going to the trees he has located and trying to experience the moment of lynching. One of the trees is in the center of downtown Los Angeles.

Ken Gonzales-Day, “At daylight the miserable man was carried to an oak…” from the series Searching for California Hang Trees, 2007, inkjet print, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

© 2007, Ken Gonzales-Day

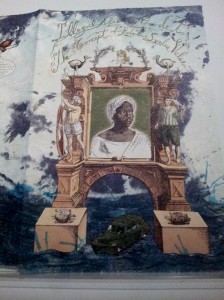

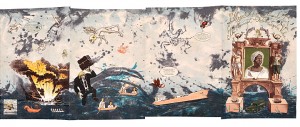

Enrico Chagoya’s long codex is full of dense references to colonialism, slavery, immigration etc. Here is one small section with the complete title of the work. Chagoya, as usual, weaves a complex tapestry of humor, politics, wicked insight, and technical virtuosity.

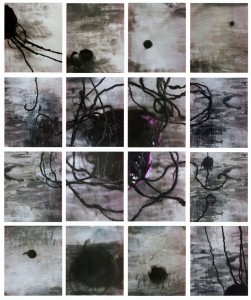

Another section of the exhibition is called “Migrating Through History” and it includes what is described as “dreamlike” imagery and a reflection of the conditions that cause migration. Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons Constellation uses hair as a metaphor of the middle passage as well as the passage from Cuba to the US. It creates an evocative and frightening reference to migration and its threats.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Constellation, 2004, instant color prints, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment. © 2004, María Magdalena Campos-Pons

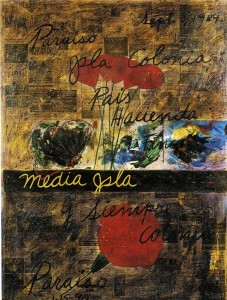

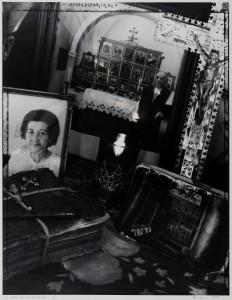

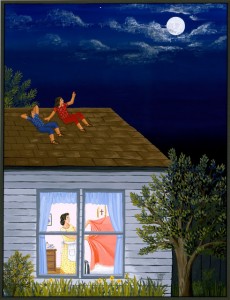

Also included in this section are personal works of domestic environments recalled in retrospect such as Maria Brito Cuba’s El Patio de Mi Casa and Muriel Hasbun’s photograph of her great grandfather’s home altar.

Muriel Hasbun, El altar de mi bisabuelo/ My Great Grandfather’s Altar, from the series Santos y sombras/ Saints and Shadows, 1997, gelatin silver print, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles H. Moore

© 1997, Muriel Hasbun

María Brito, El Patio de Mi Casa, 1990, mixed media, including acrylic paint, wood, wax, latex, gelatin silver prints and found objects, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquisition Program. © 1991, María Brito

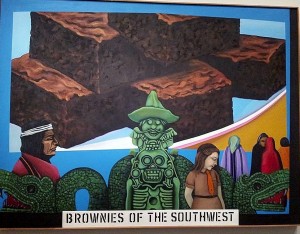

“Everyday People” included some classics, like paintings by John Valadez below left and Jesse Trevino, below right, as well as Mel Casas. So the question is why is Mel Casas excluded from mainstream discussions of Pop Art, why not include Jesse Trevino and John Valadez in Realism.

Melesio “Mel” Casas, Humanscape 62, 1970, acrylic, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment. © 1970, the Casas Family

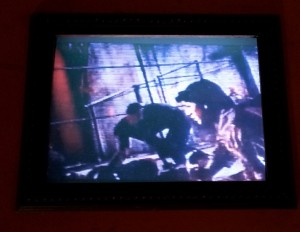

ADÁL West Side Story Upside Down, Backwards, Sideways and Out of Focus (La

Maleta de Futriaco Martínez) 2002

suitcase, flat-screen LCD monitor, single-channel digital video, color, sound;

Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen

Endowment© 2002, ADÁL

ADÁL’s footage on the small tv inserted in a suitcase in the foreground projected romantic singing scenes from 1961 West Side Story film, alternating with the realities of Puerto Rican life in 1960s NYC: “documentary footage of Puerto Ricans in New York, readings of Nuyorican poetry by Pedro Pietri, and the music of Tito Puente and Brenda Feliciano.”

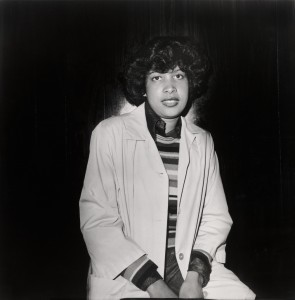

The compelling photographs by Sophie Rivera taken in NYC are based on random people whom she asked to photograph. The original huge photographs were put up in subways, giving a reality and an immediacy to Puerto Rican people as individuals. They directly connect to the long standing traditions of portrait photography all the way back to Nadar, even as the subjects assert themselves.

Sophie Rivera, Untitled, 1978, printed 2006, gelatin silver print, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment. © 1978, Sophie Rivera

“We Interrupt This Message” featured radical groups like ASCO, who pioneered street performance art and public interventions that subverted and upended media and art world stereotypes about Latinos.

Asco (Harry Gamboa Jr., Gronk, Willie Herrón, Patssi Valdez), Photographer: Harry Gamboa Jr., Decoy Gang War Victim, 1974, printed 2010, chromogenic print, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

© 1974, Harry Gamboa Jr.

“Signs of the Popular” included Carmen Lomas Garza’s genre scenes and other artists depicting aspects of everyday life. This is, of course, a standard theme in American Art History, the connection of popular art and the mainstream in genre scenes. Garza remembers her own childhood in Kingsville, Texas.

Carmen Lomas Garza Camas para Sueños 1985 Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Latino Initiatives Pool and the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquisition Program© 1985, Carmen Lomas Garza

An entire wall was filled with political posters all of them by famous artists. The graphic arts movement within this period of time was revolutionary in every sense of the word. Grouping so many powerful and famous works together did tend to diminish their individual importance, however. This is really the heart of the Chicano political graphics movement.

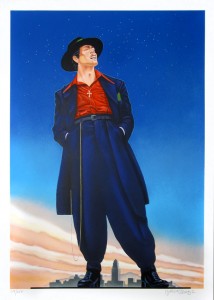

We can see at the top the stunning work of Ignacio Gomez, Zoot Suit, 2002 commemorating the central character in Luis Valdez’s eponymous and famous 1978 play, Zoot Suit. As Ramos explains in the catalog:” During the early 1940s, young and stylish Mexican Americans or pachucos wore zoot suits as a rebellious stance against their elders and against a racist environment that often dismissed them as criminal gang members.”

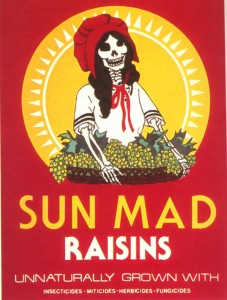

Just to the right is the famous work by Ester Hernandez Sun Mad Raisins ( The Virgin of Guadalupe Defending the Rights of the Chicanos) that needs no explanation. It could have been done yesterday.

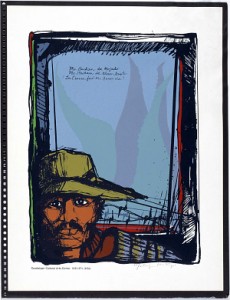

Malaquias Montoya,a crucial figure in printmaking and political action over the last fifty years is also included in this group of works. As Terezita Roma states “Montoya did not accept any division between the political and the artistic; instead his artwork forged a tight relationship in which each was intrinsic to the other.”(Malaquias Montoya, UCLA 2011 p. 8)

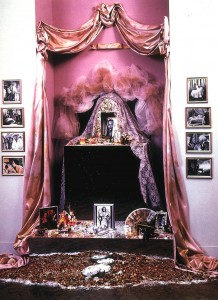

Another political section was Turning Point: Civil Rights Era, that included the famous altar by Amalia Mesa- Bains dedicated to Dolores del Rio. Amalia Mesa-Bains herself is another revolutionary, even today, speaking up about the need to be pro active and resistant to domination. She even organized Latino/a MacArthur Fellows!

Amalia Mesa-Bains Ofrenda for Dolores del Rio 1984, revised 1991 mixed media installation including plywood, mirrors, fabric, framed photographs, found objects, dried flowers and glitter Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquisition Program © 1991, Amalia Mesa-Bains

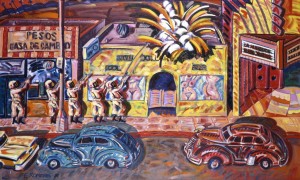

“Street Life”included the powerful work of Luis Cruz Azaceta, an artist I first encountered and wrote about in a review for New Art Examiner in 1987 He is now an old master, but still raw and compelling.

Luis Cruz Azaceta No Parking Here Any Time 1978acrylic on canvas Gift of Sharon Jacques © 1978, Luis Cruz Azaceta

But the real surprise of the exhibition came in the last room, a room full of elegant abstraction. Here was Curator Ramos’s most clear cut stand for mainstreaming Latino/a art. The artists in this gallery were working within the abstract traditions so beloved of art historians and art critics, particularly on the East Coast. Why are they never mentioned outside of Latino publications? Because they are immediately perceived, as in the review of “Our America” by the Washington Post, as imitating well known artists. The abstract artists are all tossed off as “derivative,” a tired cliché. All of these artists and this topic are worth a separate discussion.

Freddy Rodriguez was, as he has said, inspired by early Stella, but it is obvious that he has found his own way to include jazz like rhythms and rich colors, an entirely different spiritual heat that clearly speaks of the Caribbean.

Freddy Rodriguez Danza de Carnaval(det)

1974

acrylic on canvas

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 2011.10.1

He responded to the review:

“When white artists engage the history of art, critics speak of influence and dialogue. When Latino or African American artists do so, it’s derivative. This is both an antiquated way of thinking and simply historically inaccurate. Asco’s No Movies predate Cindy Sherman’s film stills. Raphael Montañez-Ortiz’s recycled films remain the most avant garde works in the history of that approach to appropriated film. Carmen Herrera was in Paris at the same time when Ellsworth Kelly was there. They were both influenced by the City of Light’s abstract art scene. ”

Furthermore his work also has many aspects such as his intense series from 2000 titled “En Esta Casa Trujillo Es El Jefe/ In this House Trujillo is Chief!” which combines sumptuous surfaces, intense content and writing.

But the reality of this exhibition is that all of these artists do fit exactly into what is going on in mainstream US art history even as they distinctly make their own contribution.

Every category corresponds. I quickly perused a half dozen new histories of American Art to see if that was true (admittedly there may be a 21st century survey I have not yet seen). But the reality is that African Americans are still barely mentioned, and Latino/as are not mentioned anywhere in general histories.

The title of “Our America” is taken from an essay by the famous Cuban intellectual José Martí who spent a good deal of time thinking about the solutions to imperialism and the independence of Cuba. America, in his writing, is a term that refers to the entire hemisphere, not just to the US, a fact people in this country frequently forget it.

José Martí wanted a revolution for Cuba to come from people who understood the inner nature of Cuba, who were not conditioned by European perspectives. He believed in the US model of cultural blending. Using this title for the exhibition points to the thesis that the artists in the exhibition are both distinctly themselves as well as part of a larger culture to which they contribute.

I conclude with this ever stunning fiberglass Man on Fire by Luis Jimeniz, his homage to Orozco’s painting Man of Fire of Cuauhtémoc, the valiant Aztec ruler tortured by fire during the Spanish conquest

Jimenez combines contemporary aesthetics and material, meaning that resonates to everyone, and the artist’s sense of history and resistance.

This entry was posted on February 14, 2014 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Chicana Artists, Conceptual Art, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.