Feminism and Performance: Joan Jonas and Gina Pane

Parallel Practices: Joan Jonas & Gina Pane on view at the Henry Art Gallery until June 18 is a rare opportunity to see two groundbreaking artists working with performance in entirely different ways.

Joan Jonas was deeply inspired by the East Coast avant-garde interdisciplinary Judson Dance Theater environment of the 1960s. They are based, in part, on the ideas of John Cage with a focus on re-thinking process, movement, body, space, and gesture as an exploration in itself. Pane emerged in Europe at the peak of the Situationist movement based in a Marxist critique of capitalism. They believed that emphasis on commodity consumption instead of lived experience was leading to passivity and alienation. Situationists stated that this “spectacle” could be countered by “the construction of situations, moments of life deliberately constructed for the purpose of reawakening and pursuing authentic desires.” But those desires are political, not simply aesthetic. Frédérique Baumgartner explains in detail the ways in which Pane’s work directly corresponds to these principles in his lengthy article“Reviving the Collective Body: Gina Pane’s Escalade/non Anesthésiéé.”[i]

Currently in Seattle there is a large conversation going on among hundreds of women artists on Facebook about feminism and art. Also, recently, a “conversation” in John Boylan’s long running series focused on performance. So thinking about the role of these two artists in relation to feminism, performance, and the significance of this exhibition is timely. There is a direct connection to Seattle in the Judson Theater Group, in that John Cage taught at the Cornish College of the Arts and developed some of his formative concepts there. Not surprisingly then much of the conversation on performance at the Vermillion Cafe on Tuesday night centered on that tradition of “process” oriented performance. On the other hand, that is by no means the only performance direction happening in Seattle. One could argue that the “Occupy” movement was street theater directly affiliated with the Situationist principles. And of course, a venue like “On the Boards”, includes a wide range of performance from all over the world, some of it very political.

Both Joan Jonas and Gina Pane were included in the important 2007 exhibition WACK, Art and the Feminist Revolution [ii] (the subject of my very first blog post!) “Parallel Practices” was curated by Dean Daderko, Curator at the Contemporary Art Museum in Houston. I am going to focus here mainly on Gina Pane, as this is her first exhibition in the United States. Jonas is still working, while Pane died in 1990.

So as a starting point, let us return to those profound differences as a result of their context: Jonas is more involved with process and experimentation with media, Pane with content and presentation. I went to the show with two artists both of whom were mesmerized by Jonas’s work particularly the recent Reading Dante III (2010) a multimedia immersive environment that makes oblique reference to Dante with a drawing of woods that also appears in a video: (for clarification for those few non Dante experts, the quote is “nel mezzo del camino di nostra vita, mi ritrovai per una selva oscura che la diritto via era smarrita” “midway in the path of our life, I found myself in a dark wood, where the straight path had been lost.” ) There are also video animations of the artist (whom we don’t see) drawing spirals that may suggest the circles of hell. The installation plays on our sense of reality and fantasy through games with photography, video, and animation.

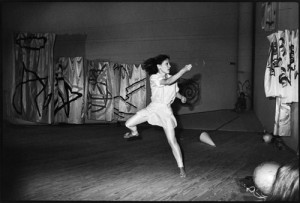

Joan Jonas, Double Lunar Dogs (performance documentation).

Presented at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston in conjunction with the exhibition Other Realities – Installations for Performance (August 1-September 27, 1981). Photo: David Crossley

What captured my friends was the immediacy of the act of drawing represented in the videos. In another work, Double Lunar Dogs, 1984, a video using state of the art techniques of 1984, engages with science fiction in an imaginary space trip in which the participants lose their way (it co-stars Spalding Gray!), but it is mainly funny and full of visual tricks. It was accompanied by a performance by the artist and some huge drawings she did as part of a performance.

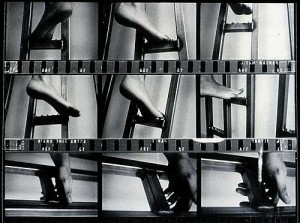

Pane, in contrast, is not at all amusing or tricky. Her work is bloody, as a result of purposeful self-mutilation. She is best known in the US for the single work Action Escalade non-anesthétsiéé (Action non anaestheticized Climb) (April 1971). It consists of a series of 69 photographs that document her increasingly excruciating climb up a specially fabricated “ladder” with steel razor blades on the widely spaced rungs. Beside it is the actual ladder which she climbed. We can see the projecting blades on the rungs which cut her feet and hands as she climbed, we feel her pain viscerally as we look at this physical artifact.

Action Escalade non-anesthésiéé (Action non anaestheticized Climb was originally accompanied by a small typewritten statement by the artist which clearly states her meaning and purpose:

Stratégie qui consiste á gravir les “échelons”/L’escalade americaine au Vietnam/Artiste – Les artiste aussi grimpent/Douleur – douleur physique á un point ou plusieurs points du corps/Douleur interne, profounde, souffrance. Douleur (morale)/ Le contraire d’une escalade anesthésiéé.

(My) translation is

“Climbing” [the word also means escalation, as in a war} –assault [can be military or verbal,] of a position by means of a ladder

The strategy consists in climbing a ladder.

The American escalation in Vietnam

The Artist – the artists also are climbing

Pain- physical pain in one or many points of the body

Pain – internal, profound, suffering. Pain (moral)

The opposite of an anesthesized climb.”

In other words, Pane has a definite political intent in this work. She is responding to the apathy of the public, by arousing them through her action to the reality of pain and injury. But, the only way that we are witness to her performance is through the photographs, arranged as a rectangle exactly corresponding in size to the ladder, and the ladder itself. She scrupulously orchestrated her actions and controlled how they were experienced. In doing that, she chose to remove the immediacy of her own pain, to make it a document of suffering, much as we experienced the war in Vietnam. I can remember at that time feeling the same way: how can people sit and watch this terrible killing on television while they eat crackers and cheese. It horrified me and radicalized me. Gina Pane felt the same way, and, in the spirit of the Situationists, she tried to break through that sense of people being numb to violence. But why did she often chose to perform without an audience and give us only her highly controlled document of it?

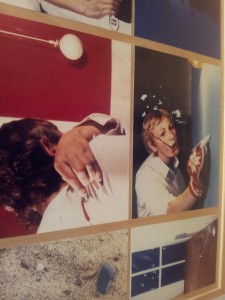

In contrast to other artists who have used bodily damage, most famously Chris Burden, who was very carefully shot in his right arm by a friend in a studio with a small audience in November 1971, Pane represents something which seems more radical and, to me, specifically feminist: she slashes her hands and feet with razors. She actively hurts herself. Razors appear in several of her other performances as well, most notably, Azione Sentimentale (Sentimental Action) 1973 and Action Little Journey I (1977).

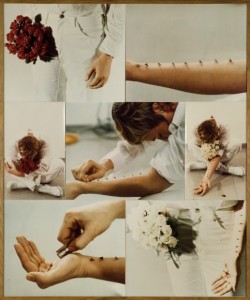

Gina Pane Little Journey, 1971 detail of photo collage created by artist, from a performance at the Pompidou Center

We associate cutting ourselves with razors with suicide or attempted suicide, particularly for women for some reason. Shooting guns is more male (and Burden carefully chose where to be shot, although likely his work was also a response to the Vietnam War). The extreme of sexual violence, domestic violence, or anguished isolation, have all driven women to attempt suicide, and this form of suicide is always enacted alone (and often unsuccessfully). It is not a topic which is found in other feminist performance art at this time.

But in the years 1969 – 73, many other women, among them the profoundly important Yoko Ono, as early as 1964 with the first performance of her extraordinary “Cut Piece,”[iv], were putting their body in a vulnerable condition, often with layered political implication. But, looking at an early well known collection of feminist performance art, The Amazing Decade, Women and Performance Art 1970 – 1980[v] we see goddesses, we see mid life crisis, we see body issues. Most related, we see works about rape. But blood is not the result of self mutilation, but of menstruation.

Peggy Phelen in “The Returns of Touch: Feminist Performances 1960 – 1980” emphasizes Pane’s influence on Marina Abramovic and Orlan, both artists who took body performance to extremes of damage to themselves in later decades, but with different dynamics. Abramovic has the audience chose how to hurt her, Orlan underwent painful plastic surgery.[vi] A later artist who dealt with blood as a direct reference to political nightmares is Regina José Galindo of Guatemala. In her performance, Who Can Erase the Traces (2003) which is about the violent dictatorships in her country; she carries a bowl of blood (not her own) into which she dips her feet, leaving bloody tracks on the street.

So Pane is unusual in her willingness to take self mutilation as a subject of her work and use it as a metaphor for political violence. She really goes beyond any performance by later artists in her willingness to not only hurt herself, but knowingly deal with that self inflicted pain as a protest of violence, This is what she said: “ [The wound] is a sign of the state of extreme fragility of the body, a sign of suffering, a sign which indicates the external situation of aggression, of violence to which we are always exposed. It introduces the vaster phenomenon of the relationship between the external world and the psychological world”[vii]

At the same time, her actions are personal. Azione Sentimentale(1973), as described in a handwritten narrative that accompanies the photographs, was a tribute to her mother.[viii] The narrative recalls a bitter sweet moment of both beauty and sadness, as she visits a cemetery with her mother. As a recording played of two women reading intimate letters, Pane carefully pierced her arm with eight thorns from a bouquet of red roses, then cut her palm with razor blades. She repeated the action with a bouquet of white roses, “then offered herself as a supplicant to the audience.”[ix]( In this case there was an all-woman audience).

The “supplicant” aspect is key to another dimension of Pane’s work, her identification with the martyrdom of Catholic saints. A few years later she created Partition, 1986 (San Sebastiaon, San Pietro, San Lorenzo), consisting of three circles which had tangible, but highly abstracted, icons referring to the martyrdom of the three saints. She identified with them, who “like her, had voluntarily accepted suffering, hoping to transform their contemporaries and make them better people.“ [x]

But, my favorite piece in the exhibition predates all of these: Enfoncement d’un rayon de soleil (Burial of a Ray of Sunlight), 1969 is a simple action: the artist digs a hole, reflects the sun into it with a mirror, then strolls away. The principle of burying sun seems so pertinent to our current state of the world. Her parallel track of environmental works is barely referenced here, and this early work does not include the debilitating physical exertion of the Actions, nor the heavy philosophical significance of martyrdom, but in its simplicity, it demonstrates a profoundly creative mind and deep love of nature.

Perhaps it was this work with mirrors that led the curator to pair Pane with Joan Jonas, who frequently uses mirrors in her work. Likewise both were pioneers in the use of video. But unlike Pane, the mirroring and video is an end in itself and self referential for Jonas. She is interesting, even poetic at times, but without a larger significance, I find her work far less moving than Pane’s.

By comparison, Pane, who would have benefited from a lot more explanation in the gallery, is a major contributor to early feminist performance art. It is amazing that this small display is her first in the United States. It also has an odd conclusion which seems to be the antithesis of her highly controlled early work: a large scrawled drawing sent to Franklin Furnace for a performance in 1979-81. Action de chasse, C’est la nuit Chérie (Hunting Action, It’s the Cherished Night) is a giant messy sketch, that again seems to superficially connect the artist to Joan Jonas, whose big rough outlines of drawings for “Lunar Dogs” are in the next room. But this work, remotely assigned to others to perform, seems the antithesis of her principles, as well as demonstrating how much her art changed.

Pane’s pairing of performance involving extreme pain with carefully controlled aesthetic presentation has failed to resonate for audiences in the U.S. because, for all our ability to spread damage and pain around the world, as well as at home, we still have our utopian illusions and a low tolerance for witnessing actual pain inside of an art venue, even in Pane’s carefully orchestrated presentation. Pane failed to wake us up from our numb state, but she certainly succeeded in creating a ground breaking art form that demonstrates her own deep concern about the world.

[i] Frédérique Baumgartner, “Reviving the Collective Body: Gina Pane’s Escalade/non Anesthésiéé”, Oxford Art Journal , 34.2, 2011, pp 252-253

[ii] WACK! Art and The Feminist Revolution, Cornelius Butler et.al, MIT press, 2007.

[iii] Ibid. illustrated p.74

[iv] WACK! pp 276, 330-352. Each time the work was performed, the context gave it a new meaning. In the Destruction in Art Symposium in 1966 in London it was part of a manifesto that declared destruction of art is linked to the “cataclysmic increase in world destructive power.” It was actually one of a whole series of works she performed “Bag Piece, Strip Tease for Three, Question Piece, Wall Piece, Wind Piece, Toilet Piece,” etc. It was most recently performed after 911 in Paris, 2003 calling it an “offering for world peace.”

[v] The Amazing Decade, Women and Performance Art 1970 – 1980, edited by Moira Roth,Los Angeles, 1983

[vi] Peggy Phelen “The Returns of Touch: Feminist Performances 1960 – 1980”in WACK!, pp.352-357

[vii] WACK! p. 279

[viii] Email communication, Perla Bianco, Galerie L’Elephant. March 16, 2014.

[ix] WACK! p. 279.

[x] Gina Pane, ‘Les Ultimes’, L’Elefante Arte Contemporanea, limited edition catalog, 93/400, unpaginated.

This entry was posted on April 10, 2014 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Feminism, Uncategorized.