“Migration” the exhibition until July 5

Where does one begin to talk about migration to the US from the Global South? Do we begin with the racism embedded in the Constitution at the founding of the United States that designated only property-owning white men as citizens? Do we begin with the history of US intervention in Latin America, our innumerable coups from 1798 to this day that over throw any government that we consider antithetical to our economic interests or which even considered enacting programs to help ordinary people? Do we begin with Free Trade Agreements that are bankrupting the small farmers of Central America and Mexico? Do we begin with the Drug Wars, the mafia, the violence, also fueled by US dollars? Do we begin with the detention system first set up to target the families of Chinese railroad workers in the 1880s? Or perhaps with the Immigration Act of 1965 which extended regulation to the Western Hemisphere? Suddenly migrant laborers without papers were counted as illegal aliens. I hope to create a book that will include art about all of these issues.

For this blog post, I will focus on the many issues raised by three artists, a poet and a community activist, in the exhibition “Migration” in the Columbia City Gallery Seattle this June.

Let us begin with Tatiana Garmendia‘s video work “New Colossus” which alters the original message of the poem inscribed near the Statue of Liberty. As we watch her sorting coffee beans more and more rapidly (an activity she was forced to do while in detention in Cuba as a child), she repeats some of the famous words of the poem “The New Colossus” by Emma Lazarus:

“Keep ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

But as the beans are sorted faster and faster into four piles, white, and shades of brown, the Lazarus poem is increasingly overwhelmed by another set of statements:

“Send me your well to do,

your educated,

your engineers,

your doctors,

your Europeans,

your light skinned,

your well fed,

your rich with many homes,

your refugees with money

your middle class with suitcases full of loot . . .

Lazarus wrote her poem in deep sympathy with Jewish immigrants pouring into this country as a result of pogroms in Russia. As it is altered in Garmendia’s “New Colossus,” it reflects our vastly changed economic and social migrations of the early 21st century. The reference is also personal, for she remembers her mother crying as she read the original poem as they entered the US for the first time.

This video is part of a series that the artist calls “The Triumphs.” For the first time, Tatiana Garmendia confronts her own childhood experience of detention and immigration. Born in Havana, Cuba in 1961 to a family of active supporters of socialism, they greeted Castro with delight. As a doctor, Tatiana’s father joined the army and worked in rural communities. But, not long after, political conditions became convoluted and he fell into disfavor. Tatiana’s family went into a detention camp in 1966 where they remained for almost three years.

As a young child, Tatiana witnessed atrocities and rape while in the detention camp. Her father was tortured and disabled. They finally reached the US in the fall of 1969.

In this exhibition Tatiana honors her father with a photograph of a blanket sewn with words that describe the methods used to torture him. It is a document of a ritual that she performed over many months.

For the artist, it was profoundly traumatic to be confronted with the reality that the US uses these same techniques at Guantánamo, and in other detention sites all over the world. The public exposure of that fact has made the depth of our hypocrisy on human rights unavoidable.

Tatiana has only now been able to begin to explore these painful memories. She draws on references to the Tarot and Santeria as a way to access her feelings. Santeria is a syncretic religion that grew from the slave trade in Cuba. It is also known as La Regla Lucumi and the rule of Osha.

Two works explore the contradiction of Castro’s charisma and the realities she experienced as a child in detention. In Fuse, we see a fusion of her own face with that of Castro’s expressing various emotions. The concept is that Castro’s mystique can actually inhabit her spirit, and those of others around the world.

In a second piece exploring Castro’s charisma, Mi Fidel, the artist takes on Castro’s mannerisms and turn of phrase; in the background are photographs of young soldiers, audiences, a soviet missile, flimsy boats of refugees trying to escape, and protest marches.

These two pieces embody the painful contradictions of multiple realities. On the one hand the charismatic leader, on the other, the suffering of many Cubans. It is believed in Cuba that Castro has a magical protector, a spiritual guardian that protects him, rides other spirits, and takes possession of them. The artist feels this as she takes on his identity, even as she knows “ in her body” as she dramatically stated, that he created great pain and suffering.

In La Patria Querida, My Dear Homeland, the artist dances with a skeleton, invoking a childhood memory of a youth who entertained herself and other children in the detention camp with a performance for which he was later tortured.

She refers to human trafficking using her own body in Border Crossing. The artist lies almost naked face up, with eyes staring, as we hear a partially coherent series of phrases “the mouth of the border has nothing to say; my border is a mouth; you crossed with nothing to say; why did you cross my home,” and many more variations on these words. These are hallucinations of a desperate woman who is either in a trance like near death state or already dead.

The motionless body is spotlighted from above, as though a surveillance airplane has found her, and at the end of the haunting soundtrack by the band Rachel’s ironically titled “wouldn’t live anywhere but here” there is the sound of a helicopter. Eerily, we realize that the woman is indeed dead in the desert, trying to cross the border, the passport stamps on her body implying it is legally entering, but she has reached the dead end of the last border crossing.

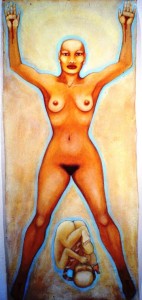

Cecilia Alvarez also addresses violence against women at the border in her larger than life painting of a nude woman, with stigmata, “Los Eternos Sacrificios, Eternal Sacrifices.”

As a radical feminist Chicana/Cubana artist, Alvarez declares her resistance to capitalism as a corrosive force that destroys people and cultures, as well as her belief in the powerful female energy that stands up to torture, trafficking, and environmental degradation. This huge woman has been tortured, but she survives in all her power, she is naked, but she is indomitable. She stands towering over us her arms raised in a gesture that is both threatening and protective. She stands guard over her unborn child as a warrior.

For the artist she refers to violence against women everywhere. One example is the Juarez murders, the murder of young factory workers on the border. Hundreds of these women have been killed with impunity, disappeared, often identified only by a random piece of clothing or a shoe found in the desert. These murders are unsolved, partly because these women are young, unknown, and defenseless. They left their home communities and supportive families in order to find a way to make a living. Unrooted, they live a bare life of squalor in toxic squatters’ camps, ride buses to a factory where they work all day in demanding and repetitive work, a toxic environment both socially and physically. They are often killed late at night when returning home from work, a bus may detour, or a car may take them.

In “La Tierra Santa, Holy Earth”, Alvarez presents a defiant mother, hair flying behind her. She gestures “stop” with her out turned palm. She is the antithesis of the passive and much worshipped Virgin of Guadalupe. This holy woman, with the moon as a halo, protects four children of the Brazilian Yanomami tribe with her body. At the bottom of the painting the span of her legs guards a duck, panther, turtle, fish and snake. The Yanomami are the largest indigenous group living in the Brazilian rainforest. Today they are under severe threat of extinction from disease, and land loss, from mining, logging and cattle ranching.

This indigenous woman is protecting her progeny and the creatures of the earth, the victims of ravaging development by multinational companies, forcing migration of species as well as multiple extinctions. Because they have lived close to the land and in communion with it for thousands of years, indigenous peoples are leading the way in current resistance movements to ecological disaster and climate change ( see previous post). Alvarez’s painting honors them.

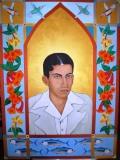

Cecilia Alvarez’s third painting is the centerpiece of an altar dedicated to her father, Jorge Guillermo Alvarez, who came from Cuba to the US in the 1940s in hopes of earning a better living. As an albacore fisherman he respected the environment, he refused to use nets. Environmental consciousness is a deep component of Alvarez’s work.

Cecilia Alvarez was shaped by her childhood on the border of Mexico, in both San Diego and Tijuana. In Mexico she experienced a warm extended family at her grandmother’s home. She spoke Spanish and connected to the long history of her community. In the U.S., she was forced to speak English and stripped of her cultural values. She remembers that Latino students were lectured on hygiene in elementary school, while white American students took art.

In front of the painting of her father, an installation of crosses movingly addresses the price of resistance, of migration, both on individuals and on the planet with the following texts:

“In memory of all the species that have lost or are losing habitat, a future, and have nowhere to migrate

“In memory of all those known and unknown who have perished trying to migrate and escape violence

“In memory to the women and children known and unknown who are fleeing natural and social catastrophe and who are victims of slavery”

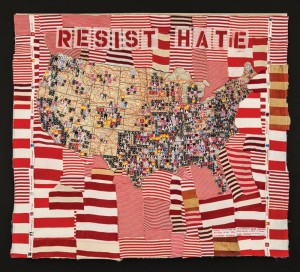

In the collage “Resist Hate,” Deborah Faye Lawrence creates icons for ten types of hate groups in the US expanding on a map from the Southern Poverty Law Center. We see the ten icons covering the map of the country, densely in most areas. They are actually only a few of the many hate groups documented by SPLC, but Lawrence’s map is far more intense than the SPLC map. In many states she has covered almost the whole state with icons of the following groups “Anti Islamist, Ku Klux Klan, Neo Nazi, Neo Confederate, Black Separatist, General Hate, Anti LGBT, White Nationalist, Racist Skinhead, Christian Identity. Her headline, urgently calls on us to “Resist Hate.” Hate, as seen in this map, is often based on race and religion.

There is much we can do every day to counter the hatred on the planet with non violent activism, both on the micro level and the macro level, but it takes a lot of awareness, a lot of constant effort. Violence is so much easier and so much more available and promoted and accepted.

But to resist hate means to find another way forward. I am reading Mark Kurlansky’s book on the history of non violence, “a dangerous idea” as he calls it. He gives us the history of many defeated peace movements, but he points out that history suppresses the successes of non violent civic disobedience. For example during World War II, Denmark gave lip service to the Nazis, but then subverted all of their programs, most significantly, in preventing the deporting or Jews. Connecting to Alvarez’s conviction that capitalism is the primary evil, Kurlansky dispels myths about wars: they are mainly about economic gain, but they are frequently promoted through hate.

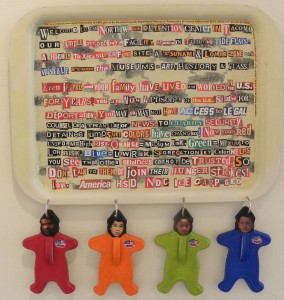

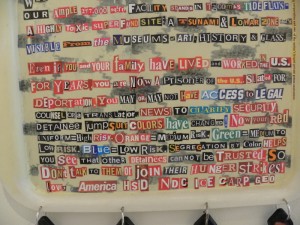

Lawrence’s work, “Welcome (NW Detention Center),” is a partner to the Hate Map. Fostering hatred of the “other” and pursing detention go hand in hand. “Welcome” details that system, its private corporate ownership, its absurd and arbitrary regulations, and its abuse of human rights.

The meticulously constructed text, made from cutting out individual letters, says

“Welcome to the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma. Our ample 277,000 sq.ft. facility stands in Tacoma’s Tide Flats- a highly toxic superfund site; A Tsunami and Lohar zone that’s visible from the museums of art, history and glass. Even if you and your family have lived and worked in the US for years, you are now a prisoner of the U.S. slated for deportation. You may or may not have access to legal counsel or a translator or news! To clarify security, detainee jumpsuit colors have changed! Now your Red uniform= high risk. Orange=medium risk. Green=medium to low risk. Blue=low risk. Segregation by color helps you see that other detainees cannot be trusted. So don’t talk to them or join their hunger strikes!”

Around the edge, the small strip of writing refers to the administration of the Northwest Detention Center by the private corporation GEO. “NDC is a criminal alien requirement prison [CARP], part of the Homeland Security Department’s Bureau of Immigration & Customs Enforcement [ICE], owned and operated by GEO, a profit making corporation and one of the nations’ largest private prison contractors.” GEO receives $159. per night per filled bed from our tax dollars. There are 32,000 detention beds in the US, not counting the newly built family detention centers located in remote areas, near the border so that they do not need to comply with any US laws.

The text of “Welcome” is collaged on a 1950s tv tray; below it hangs four cookie cutters, made into figures with various shades of skin color and wearing four colors of uniform. The “hanging” of these figures and the use of cookie cutters implies that they are helplessly caught up in a system beyond their control, a system that is removing them from ordinary life and heading them toward death.

Deportation for many of the people who are detained for no crime whatsoever except a burned out tail light or expired license, or perhaps, wearing a tattoo that might suggest gang membership from thirty years ago, or a DWI from forty years ago, that deportation often means death, at the least the death of that person’s life as they lived it, at worst literal death in the country to which they are sent, which often is not their home country.

Furthermore, there is no “path to citizenship”. Obama’s effort to create that path, convoluted and incredibly drawn out as it was, has been blocked in the courts. Despite renewed claims that only “convicted criminals, terrorism threats or those who recently crossed the border.” are being detained, the Detention Center in Tacoma is completely full, 1496 people in mid June , (the capacity is 1500), with almost all people who have not committed crimes. We pay $149. per day from our tax money to GEO for each person. No wonder the incentive is to keep the maximum number of detainees there under insufferable conditions. These detainees do not have any of the rights of criminals, a right to a lawyer, to a jury, to recreation, or even to decent food. They work for $1. a day ( if they were working for nothing it would be slavery), to run the facility.

Particularly immigrants from the global south are consistently racially profiled both by local police and by the society at large despite the fact that they are incredibly hard workers, doing work that most of us cannot or do not want to do.

Lawrence concisely captures these tragic contradictions.

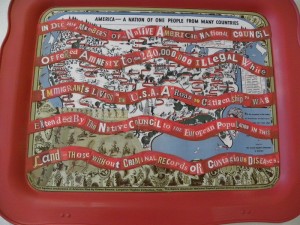

Next Lawrence takes an ironic tone in the “American Amnesty Tray” which highlights the action taken by the Native American Council in December 2014, granting amnesty to 240 million illegal white people. She has placed this text over a 1940 map of the U.S. with the title, “Against Intolerance in America” by Emma Bourne.

Increasingly Native peoples especially in the Northwest are reclaiming their ownership of the land. In Canada, where treaties were not signed, the First Nations are winning their claims in court, effectively blocking pipelines and other ruthless development

Crucially, Lawrence includes the fact that “a ‘road to citizenship’ was extended by the Native Council to the European Population in this land – those without criminal records or contagious diseases. “ Since no road to citizenship has been offered to the thousands of undocumented workers in this country, that fact creates a dramatic point.

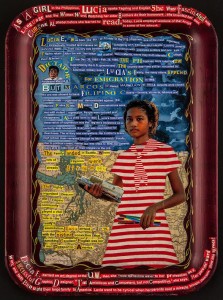

The last tray by Lawrence details a successful immigration story. That is, of course, why so many people have come here. There are successes, many of them. The foundation of our country is based on the energy brought by people from all over the world. Lucia E tells the story of a Filipina immigrant who fled the Marcos dictatorship and then followed a path to citizenship in this country as a result of community support and her ability to speak English.

Many of the people who are currently rounded up by the immigration and detention system do not speak English, and do not have a way forward to become legal. Sometimes they missed a single document sent to them years ago, or a single ordered court appearance, perhaps because of changing addresses. People who are in fear of their lives if they are sent “back” or who have been trafficked have the possibility of what is called “relief” or legal procedures that can lead to citizenship. No one else has any recourse.

Deborah Lawrence grew up in Southern California with working class parents who had deep roots in activism and left wing politics. She moved constantly as a child; art was her means of survival. She works with collage in the tradition of Dada artists who intentionally cut up magazines as a way of attacking capitalism. In her case, she confronts abuses in many forms, particularly against women, but she also honors women who play a leading role in resisting oppression. Her art work is defiant and straightforward, but also humorous and respectful.

Each of these artists offers multiple perspectives on migration ranging from the torture and abuse of detention, human trafficking and violence against women, abuse of children, environmental degradation, and the corrosive role of capitalism, to the hopes and dreams for a better life, that, in some cases, are realized.

In addition to these visual artists, our exhibition included a presentation by the activist Maru Mora Villalpando who gave us an overview of migration activism in the Northwest that includes advocating for the berry pickers in the Skagit Vallery as well as calling attention to the detention center in Tacoma. Villalpando has been able to get media coverage for an extended hunger strike in Tacoma, as well as calling attention to violence by guards against detainees. She is an articulate national advocate for the detainees.

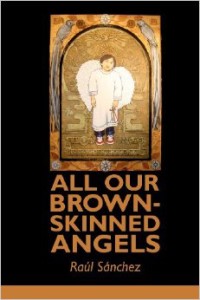

Finally, we had a series of poems by Raul Sanchez, both his own work and the writings of others, which evocatively traced the stages of a northern migration from riding the “Beast” as the train north is known, to experiences at the border, to the essential work of “All Our Brown- Skinned Angels” as his book of poetry is titled. In this book, he presents exquisite poems honoring Latino workers in our society, the angels of the title.

“Migration” as a process and a concept encompasses all of these issues and much more. It encompasses all of us.

Even as xenophobia seems to be reaching a new pitch in the US this summer of 2015 among ignorant politicians and the general public, there is no denying that this nation has always been a nation of both migration and xenophobia. Other than the Native American population we have all come from somewhere else. We have enriched the country, but each migration has suffered hostility and resentment from those already here. As pointed out in an editorial in the New York Times on July 10, for example, when the Irish came in the 19th century they were vilified as criminals. After the Chinese finished building the railroads for the moguls, they were run out of town, and immigration prevented, many were held in detention. And so now we have Mexicans and Latinos , those who, in fact, actually are holding our country together.

This entry was posted on June 17, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, Barack Obama, Immigration, Indigenous activism, Migration, Uncategorized.