Some Public Art in the Central District: Jimi Hendrix Park and the Shadow Wall

Scott Murase with Murase Associates designed the recently completed Shadow Wall sculpture in the Jimi Hendrix Park. The same firm beautifully designed the whole park to loosely suggest a guitar.

From the entrance at 2400 S Massachusetts Ave, the Hendrix signature on the wall leads us on a purple (now faded to blue) swirling path inscribed with the poetic words of two Hendrix songs “Angel” and “Little Wing.” The beautiful words remind us that Hendrix was a poet as well as an extraordinary musician.

The lyrics continue:

“She stayed with me just long enough to rescue me And she told me a story yesterday about the sweet love between the moon and the deep blue sea. And then she spread her wings high over me.

“She said she’s going to come back tomorrow and I said fly on my sweet angel, fly on through the sky. Fly on my sweet angel tomorrow I’m gonna be by your side. Sure enough this morning comes to me silver wing silhouette against a child’s sunrise And my angel, she said to me, today is the day for you to rise. Take my hand, your’re gonna be my man You’re gonna rise

And she took me high over yonder

And I said fly on my sweet angel Fly through the sky Fly on through the sky Fly on my sweet angel. Forever I will be on your side. ( 1967)

Here you see the original purple sent to me courtesy of Scott Murase.

Horizontal strips provide a succinct biography of Hendrix’s amazing life from humble beginnings in the Central District to world-wide fame.

For example one strip states: The original Jimi Hendrix Experience disbanded in June 1969. On August 18, 1969, Jimi’s new ensemble group Gypsy Sun and Rainbows headlined Woodstock Art and Music Fair in upstate New York, where Jimi delivered unforgettable rendition of “Star Spangled Banner.”

The path leads to the large red butterfly that hangs over the seating area, intended for performance and community gatherings.

A portrait of Jimi Hendrix dominates the newly installed Shadow Wall. From that focus it swirls out with a perforated steel curtain that creates vibrant shadows, including silhouette cut outs of the musician.

Appropriate to the incredibly innovative Hendrix, it transforms a static memorial sculpture into a vibrant space filled with rhythms that echo and fold back on themselves as we walk through it. The patterns in the shadows suggest swelling music. Hendrix came from great poverty and emotional challenges in his youth, but his staggering musical talent on the guitar led him to world wide fame.

This entry was posted on April 25, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.

“Climate Change Alert through Arctic Aesthetics” by Jean Bundy, Art Critic based in Anchorage Alaska

This paper was presented in the International Art Critics Association session at the College Art Association February 2020 Jean Bundy is the Climate Change Envoy for AICA-INTERNATIONAL

Introduction

In the Eighteenth Century Captain Cook era, when exploration and desired acquisition of the Pacific Northwest was mapped and illustrated, it became evident that these locations had abundant flora, fauna, and minerals. Encountering the Indigenous, who were often abused, was a resource for survival, scientific research, and financial gain, which continued through the Russian takeover, the Alaska purchase, 1867 and yes, through Statehood, 1959.

In the Twenty-First Century, Alaska Natives and other Arctic aboriginals are finally being appreciated for stewardship of their lands and acute awareness of Bush Climate Change. Explorers/scientists and tourists venture to the 49th state, not to claim territory, but to paint, photograph, wilderness adventure, and observe/document the Arctic with cameras/instrumentation unimaginable to Cook.

Alaska’s changing environment has been obvious to all residents for the past several decades. Increased forest fires, die-offs of: Salmon, Murres, and Seals, bug infested trees, and toxic algae, are evident in urban areas as well.

Lack of snow and melting glaciers impact Bush living as seacoast towns are eroding, and icepacks needed for safely hunting sea mammals are shrinking. Increasing amounts of CO2 found in the ocean are also leaching out of the ground as tundra melts, witnessed by rising/falling Pingos.

These are humongous problems that can’t be solved without cooperation from governments willing to shell out large sums of cash while putting their countries on energy diets and adopting more user-friendly recycling and pollution programs.

So, does educating the public to the rapidly melting Arctic through aesthetic visualization do any good? And are there ironic silver linings found within Global Warming such as: longer growing seasons, anthropological discoveries, Arctic communities benefitting from installation of fiber-optic cables because of the surfacing Northwest Passage?

The Christies’ Symposium, June 11, 2019, stressed that “art brings the invisible to our attention.” So why not use this phenomenon to extend Heidegger’s definition of ‘Being’ by cleaning up the living Earth?

Aesthetic narratives, that steamroll Captain Cook’s or Averill Harriman’s masculine adventuresome fantasies, get replaced by gender-neutral themes: oceanic pollution, sea ice melt, coastal erosion, and respect for Indigenous populations.

Six artists working across the Arctic possess different backgrounds which culminate in multiple perspectives, making art to heighten awareness of Climate Change, thus heralding the aesthetic importance of the North.

1: Ásthildur Jónsdóttir (Iceland) ‘Arctic Aesthetics, 2019’

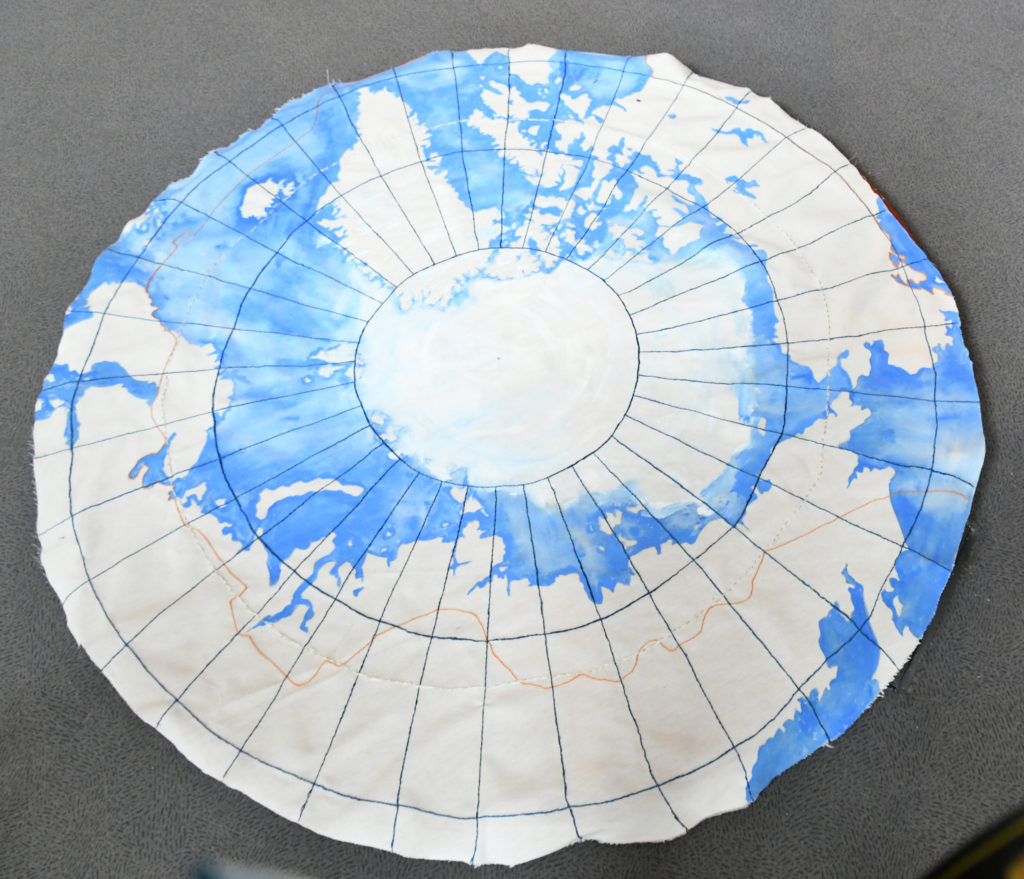

Jónsdóttir hand stitched/painted the Eight countries that reside in the Arctic Circle, saying she wanted to be “involved with issues concerning the ecology of the planet….[and to encourage engagement] in the beauty of the Arctic, both physically and psychologically.” Her art moves beyond craft morphing into fine art, overlaying the essence of ancient artifacts upon contemporary art making. Jónsdóttir’s piece was displayed at the Second Arctic Arts Conference, Rovaniemi, Finland, June 2019, while a similar photographic map was projected at the First Arctic Art conference, Harstad Norway June 2017.

Most maps are shown from the vantage point of the equator where notable historic travel, transportation and colonial entrepreneurship occurred. Looking at the world from the top down, disorients, but ultimately creates a greater sensitivity about this region and its importance to the rest of the Globe, in light of accelerated melting.

Referencing Alaska, beginning with Russian colonization, and continuing under US ownership, white Settlers came and established towns and businesses without recognizing the historical rights of Indigenous populations. The Alaska Natives Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) 1971 resolved aboriginal land rights by transferring 40 million acres of land to about 200 corporations in which Alaska Natives are shareholders. Because the corporations are businesses and not governments, ongoing disputes between Native villages and the Federal/State agencies continue.

Scandinavia’s history, like Alaska’s, is about white Settlers/entrepreneurs disrupting the semi-nomadic Sámi ancient traditions. Like Alaska Natives, Sámi view land as a borrowed gift/resource for hunting and fishing and don’t conceive of land as Western ownership/real estate. In the late Nineteenth Century, the Norwegian government began appropriating Sámi lands which were resource rich and economically viable. Sámi were ordered to assimilate into Norwegian culture and language; children were sent to state run boarding schools like Alaska Native children.

In 1987, the Norwegian government gave Sámi their own parliament, with other Scandinavian Sámi parliaments also established. But many feel this attempt to re-establish/recognize Sámi governance is window dressing. For example, governments cull Sámi reindeer herds, rationalizing there are too many per acre. In reality, grazing lands are more remunerative developed for natural resources.

It has always been perceived that the North can’t think for itself. There is the “North” created by outsiders, which often overtakes insider “North.” The intent of recent Arctic Arts Summits is to visualize cultural similarities between Arctic countries which are experiencing similar political and environmental frustrations.

However, attitudes are changing as Indigenous groups are becoming appreciated for their acute understanding of Nature’s harmonies/balances, as they strive to be guardians of all things land/sea related. The outside world still has the stronger hold on mineral rights as well as control of hunting and fishing. However, Tourism has become a new resource for Arctic prosperity, with Indigenous art the preferred commodity sold.

Sadly, fake Sámi and Alaska Native art is also popular. Many residing in the North feel there are too many tourists, too many cruise ships, polluting/eroding natural surroundings.

Finding an Arctic voice, which appreciates the beauty of landscape/wildlife, while coping with Twenty-First century development, continues to challenge ancient Indigenous ways, and now the impact of Global Warming. Can there ever be a balance between development and the environment? Exhibiting aesthetic objectivity helps imagine solutions.

2: Brian Adams (Iñupiaq) photographer, ‘Kivalina Sea Wall, 2007’

Adams’ photograph seeks humanity beneath the surface. Kivalina is an island of four hundred Iñupiaq residents in the Northwest Arctic Borough, which is slowly returning to the sea. Residents hunt the Bowhead whale, which becomes harder as ice packs grow thinner. Before missionaries were sent to Alaska and imposed Western ideas of stationary communities upon Natives, seasonal relocation to inland fish camps was the norm.

Disruption becomes a much bigger deal when towns with buildings, bureaucracies, and communication systems are permanent places. Boxes and sandbags are a temporary fix to the reality that endangered villages will eventually have to move and at great expense.

3: Marek Ranis (Poland/USA), associate professor at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte ‘Faith, 2017’

Ranis’ Faith (2017), a transparent digital print of an inverted oil rig superimposed against an Arctic sunrise/sunset, situated in a window, mimics stained glass, suggesting sacred venues of contemplation and rejuvenation. Ranis positions this handsome machine, center stage, like the image of a saint in a cathedral window. This upside down rig allows viewers to pause and contemplate mechanisms that extract needed oil, providing Norway with wealth and social services, but also the possibility of an environmental disaster.

However, the gorgeous landscape behind the rig, produced by the sun’s energy, can also generate devastation without man’s assistance. The sunrise/sunset becomes a metaphor for considering frictions between increased mineral exploration, and Sámi reindeer herders lobbying to preserve needed pasture lands. The Arctic tug between preserving raw beauty and harnessing nature for profit continues throughout all communities.

In Alaska the debate about whether to allow copper mining near Bristol Bay, home to commercial and recreational Salmon fishing, continues with the conundrum that providing jobs to Indigenous locals, who can’t rely on total subsistence, may pose environmental consequences if a mine were to leach toxins. Harkening back to early Twentieth Century ‘Heideggerian’ discussions on the potency of the machine age, then fast forward to the Twenty-First century with its sophisticated automation, has progress been made when it comes to utilizing technology safely/efficiently and at what expense to the environment?

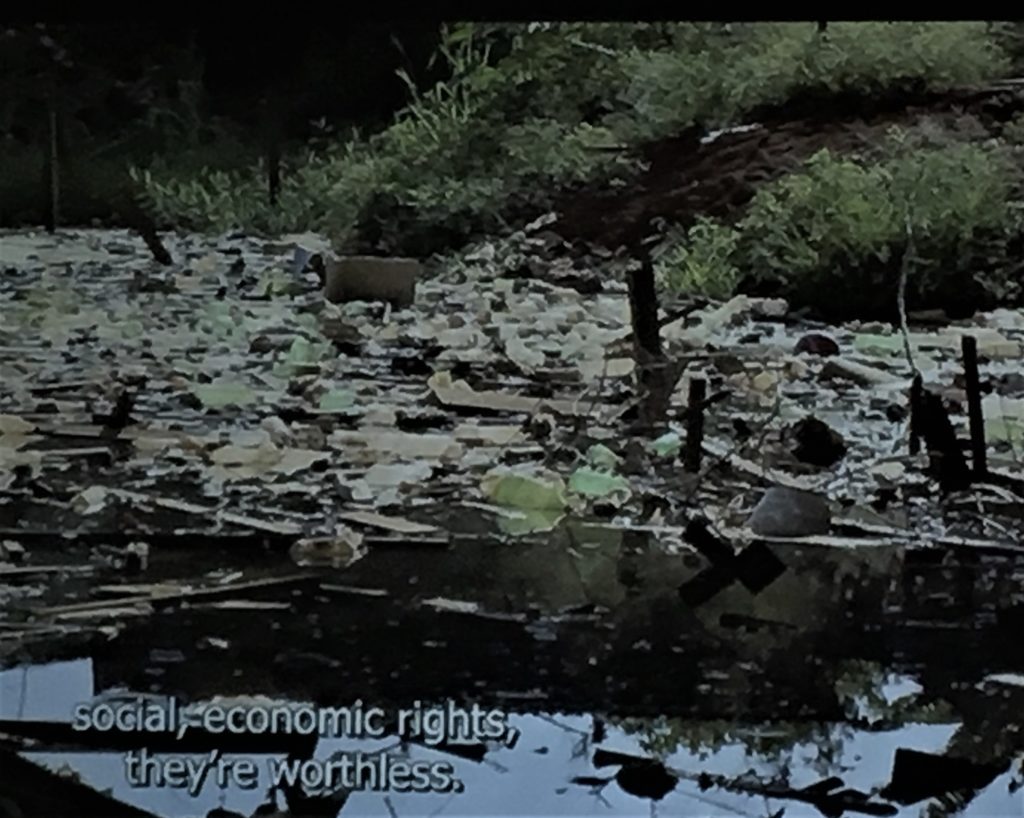

4: Geir Tore Holm (Norwegian), ‘Fughetta, 2014’

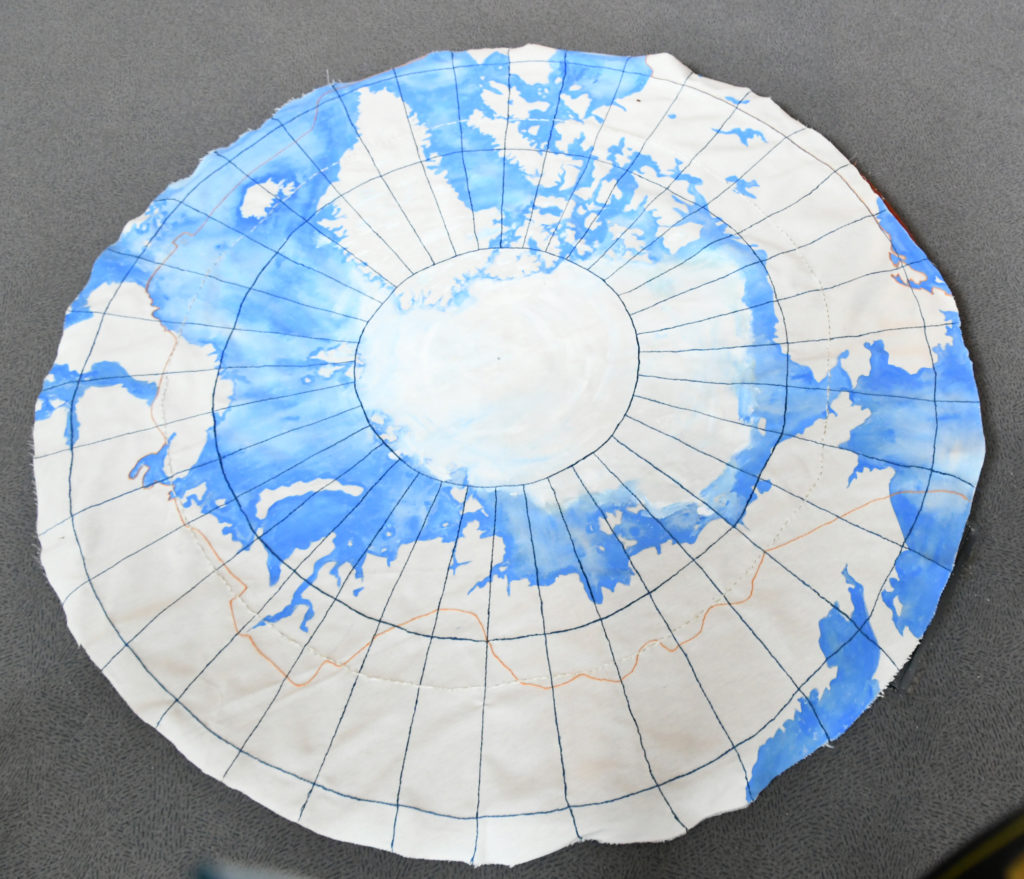

Holm’s Fughetta (2014), are reindeer carcasses soaked in resin and electrified, resembling The Human Body Exhibition. Holm, who lives on a farm, is reconfiguring reindeer, the livelihood and sustenance of the Sámi, as a surreal chandelier or butchered meat hanging/aging in a cooler. By isolating reindeer from grazing sites, viewers are forced to think about Nature that can quickly be refigured into a heartless commodity.

Is it proper for the Norwegian government to cull Sámi herds, so the real estate can be developed? Perhaps further Climate Change will make what seems unnatural, the taken-for-granted norm. Fughetta is also reminiscent of compositional Fugues which have multiple voices. Fughetta suggests musical rhythms, as the reindeer remains swing from a ceiling. Pendulum motions suggest hangings too, and the tug of war between environmental groups and mining companies.

5: Allison Akootchook Warden (Iñupiaq) and Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit) video, ‘Envoy, 2016’

Warden, known for choreographed rap, and Sitka filmmaker Galanin, produced the video Envoy (2016). One segment shows a Polar Bear frantically pacing in a not so politically correct ‘Natural History’ concrete space. Until recently, zoos kept animals confined as specimens, giving little thought to their environmental needs.

The Polar Bear has become the poster child for Global Warming as Arctic sea ice, the bear’s habitat, is melting. Ironically, zoos may be the only places Polar Bears will exist, hopefully better than the one pictured.

In Warden’s footage the matted bear who resides alone in a concrete jungle represents environmental carelessness at its worst, as well as man’s lack of foresight. Although, not the cuddly creatures appearing in Disney footage, or Coke commercials, Polar Bears deserve saving.

James Temte (Northern Cheyenne) adjunct professor at Alaska Pacific University, ‘THINK NEXT OVER NOW, 2019’

6: James Temte (Northern Cheyenne) adjunct professor at Alaska Pacific University, ‘THINK NEXT OVER NOW, 2019’

Temte’s outdoor billboard-esque photograph is made of large plastic tessellations, picturing a pre-teen standing in a field, clasping a handful of dirt/vegetation. The youth could be male or female of any ethnicity. This young person is wearing a logoed t-shirt and warm-up jacket that is also gender-less. Hair is shoulder length with bangs—any kid’s cut.

Some of the background squares have deliberately been omitted, creating black emptiness, suggesting what life might be like when Climate Change erases the Earth, as we know it. Since this is a parking area, ‘handicap’ signs not only couldn’t be removed, they become part of the composition. One of the ‘handicap’ signs fetched up on the breast pocket of the youth’s track suit and looks like the garment came with that label.

This entire piece becomes a narrative for Global Warming, with the ‘every-youth’ cradling a piece of Earth. Yes, we are ‘handicapped’ as we begin to figure out how to balance productivity with cleansing the environment. Each word of ‘THINK NEXT OVER NOW,’ executed in different fonts, makes a statement, becoming contemplative verbiage hanging over the youth, landscape, and all of us.

Driving by Temte’s mural forces Anchorage residents, who are going about their daily routines, to consider Climate Change—subtleties override being scolded. Global Warming has been happening/accelerating/ignored since the Industrial Revolution and can’t be fixed ASAP, which really depresses teens like the one depicted in this mural.

Of note: mysterious dust was found in late Nineteen Century Greenland, by Swedish explorer Erik Nordenskiöld, finally identified as coal, blown North from the Industrial Revolution of Europe and North America (Hatfield 174,175).

According to Temte, “I see a need for including art specifically public art in the climate change conversation. As a scientist I know that data collection is important to track the impacts occurring in the arctic however, looking at an excel spreadsheet of data points may not be as compelling as seeing our stories depicted in murals across our communities. The language of art can connect with everyone from children to our elders. The more that communities can come together and agree that actions need to be taken and that we are all a part of the solution the more ground we can make on addressing and potentially slowing the effects of climate change.” Like all things social and political, change doesn’t occur until a panic button is visualized, and hopefully pushed.

Conclusion

At Christie’sSeminar, New York City, June 11, 2019, it was agreed that Global Warming was complicated and shouting at people to reduce Carbon Footprints fails.

According to a wall label at the Arktikum Museum, Rovaniemi, Finland, “The world is becoming increasingly connected, through shared social, environmental, cultural and economic challenges, requiring different forms of transnational knowledge and solutions.”

Last April’s Notre Dame fire proved art is the greatest metaphor for Globalism. On Place Jean Paul II, a plethora of ethnicities stood, prayed and cried, while millions worldwide watched on electronic media, as fire fighters saved most of the structure. Instantly monies poured in from all parts of the Globe, because people worldwide want to feel a part of rebuilding a monument which has endured the historical dichotomy: suffering and euphoria. Fire didn’t care about cultural divides; it just enjoyed melting lead and smoldering centuries old wood into charcoal.

Art promotes the invisible through visual dialogue, museum or neighborhood involvement, and self-awareness of belonging to place. Artists with a sincere investment in the Earth are not only stewards, but beacons for the mess that needs cleaning-up.

Photographs by David Bundy except Brian Adams (Iñupiaq) photographer, ‘Kivalina Sea Wall,

Bibliography Most information was gleaned from reportage at the First Arctic Arts Conference, Harstad, Norway, June, 2017 and the Second Arctic Arts Conference Rovaniemi, Finland, June, 2019, which became online articles (www.anchoragepress.com) and an AICA-International 51st Congress, Taiwan, Fall 2018, presentation.

Papers by Jean Bundy

Arctic Environmental Challenges Through Virtuality, is available through AICA-INT (AICA Taiwan Congress, November 14-21 2018)

ART SLEUTH: Norway’s Arctic Arts Summit (July 4, 2017)

ART SLEUTH: Norway’s Arctic Arts Summit — part 2 (July 11, 2017)

The Sleuth Takes Arctic Art to Taiwan –Part 1 (December 5, 2018)

Alaska Native Artists Help ‘Make the North Great Again (June 24, 2019)

James Temte’s Outdoor Mural — It’s Not Outsider Art (November 4, 2019)

Temte, James. “Re: Jean Bundy for the Anchorage Press.” Message to the author. October 30, 2019. E-mail

Books: Quoted or Consulted

Fringe, edited by Maria Huhmarniemi, ISBN: 978-052-337-156-9; Pdf ISBN: 978-952-337-157-6

What is the Imagined North? Daniel Chartier, Arctic Arts Summit, 2018, ISBN: 978-2-923385-25-9

Arctic Pocket Book,Artikum Service Ltd.2017, Finland, ISBN: 978-952-938576-8

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time,translated by Joan Stambaugh. State University of New York Press, Albany, 2010

——The Question Concerning Technology, translated by William Lovitt.Harper and Row, New York, 1977

McAleer, John and Nigel Rigby.Captain Cook and the Pacific.Yale University Press, New Haven, 2017

Jamail, Dahr. The End of Ice.The New Press, New York, 2019

Hatfield, Philip. Lines in the Ice. Philip Hatfield, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 2016

Adams, Brian. I AM ALASKAN.University of Alaska Press, Fairbanks, 2013

This entry was posted on March 19, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.

“Between Bodies”

Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington Oct 27, 2018 – Apr 28, 2019

The eight artists in “Between Bodies” take us from the air, to the minerals deep in the earth, the untamed rivers, the smoking forest, and finally to the sounds and microorganisms of the deep sea. They explore metaphors of sexual transformation, intraspecies and trans species communication, future avatars and present voices. We witness the fragility and destructibility of nature, as we experience its power and invisible miracles. All of these artists care deeply about the dire condition of the planet and seek ways to halt or reverse the violent assaults perpetrated by those in power. They give us imaginary futures based on present catastrophes.

Curated by Nina Bozicnik “Between Bodies” features eight artists who work with the interface of technology and nature, what she calls “humans and more than humans” and the “legacies of violence” on the planet. The artists work in multiple media: archive, text, sculpture, video, virtual reality as well as across disciplines, science, art, history, science fiction, poetry, storytelling.

Candice Lin and Patrick Staff Hormonal Fog. 2016-2018. Hacked fog machine, dried herbs, herbal tincture, wood, plastic and miscellaneous hardware. Image courtesy of the artists and ICA, London. Photo Credit: Nick Tudor.At the entrance we pass through Hormonal Fog by Candice Lin and Patrick Staff. Herbal tinctures (licorice root, hops, black cohosh root, and dong quai root,) dispersed by a fog machine fill the air with anti testosterone herbs that gentle our aggressive tendencies, one way forward for the planet.

Caitlin Berrigan’s challenging multi-part Treatise on Imaginary Explosions, Vol. II. 2016–2018 requires us to give up real time and surrender to its narratives, fragments, and multipart structure. In the main theme transgender scientists prematurely trigger simultaneous volcanic eruptions all over the planet. Berrigan links patriarchal extractions of the earth and the rape of the individual body, identifying these eruptions as an opportunity for radical transformation.

photo by Susan Platt

In two facing spaces the Treatise includes a “digital elevation topographical rendering” of Eyjafjallajökull, a volcano in Iceland juxtaposed to physical objects including a physical chunk of mineral on a brass chain, journals, a necklace/talisman suggesting interstellar travel and several videos. There is also an acoustic environment that we are invited to activate. The seismic vibrations echo inside our bodies.

Scrolling over a video of a rotating mineral, a poem suggests:

“Alliances of friendship outlast and overcome

any force of social or environmental trauma.

First we must find each other.

We must cohere.

In alliance, we move together.

We mineralize.”

Dye-sublimation prints on canvas.

Courtesy of the artist and Instituto de Visión, Bogotá.

In the main gallery Water Portraits, Carolina Caycedo’s huge prints on canvas, hang from ceiling to floor surrounding us with giant kaledeiscope-like images of rushing river waters. Some evoke giant vaginal labia.

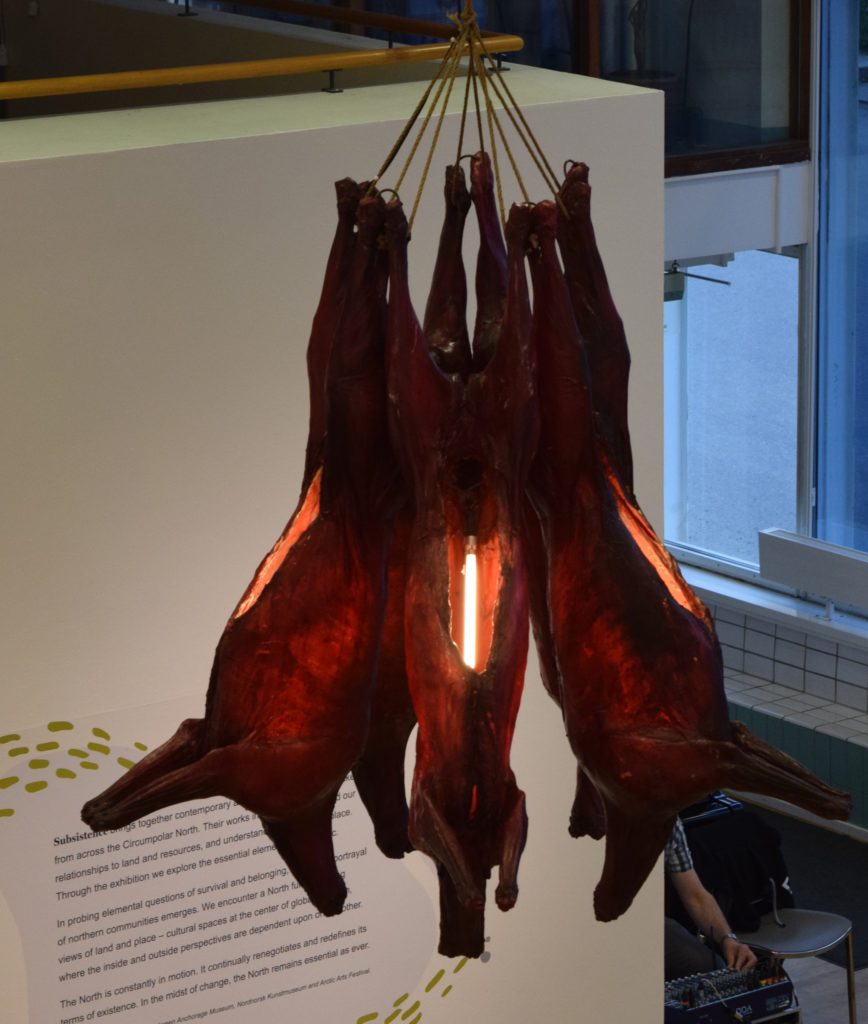

Caycedo has worked for twelve years on “Be Dammed,” a project that looks at the impact of dams in Colombia, specifically on the Yuma River, also known as the Magdalena River, where no fewer than nineteen corporate dams are planned. The artist spent months speaking with local indigenous peoples (she has her own roots in the area) about their lives before and after the dams.

Her film A Gente Rio/We River underscores both the large scale corporate destruction of lives on the river and intimate details of survival such as a hand holding tiny crumbs of gold sieved from the river.

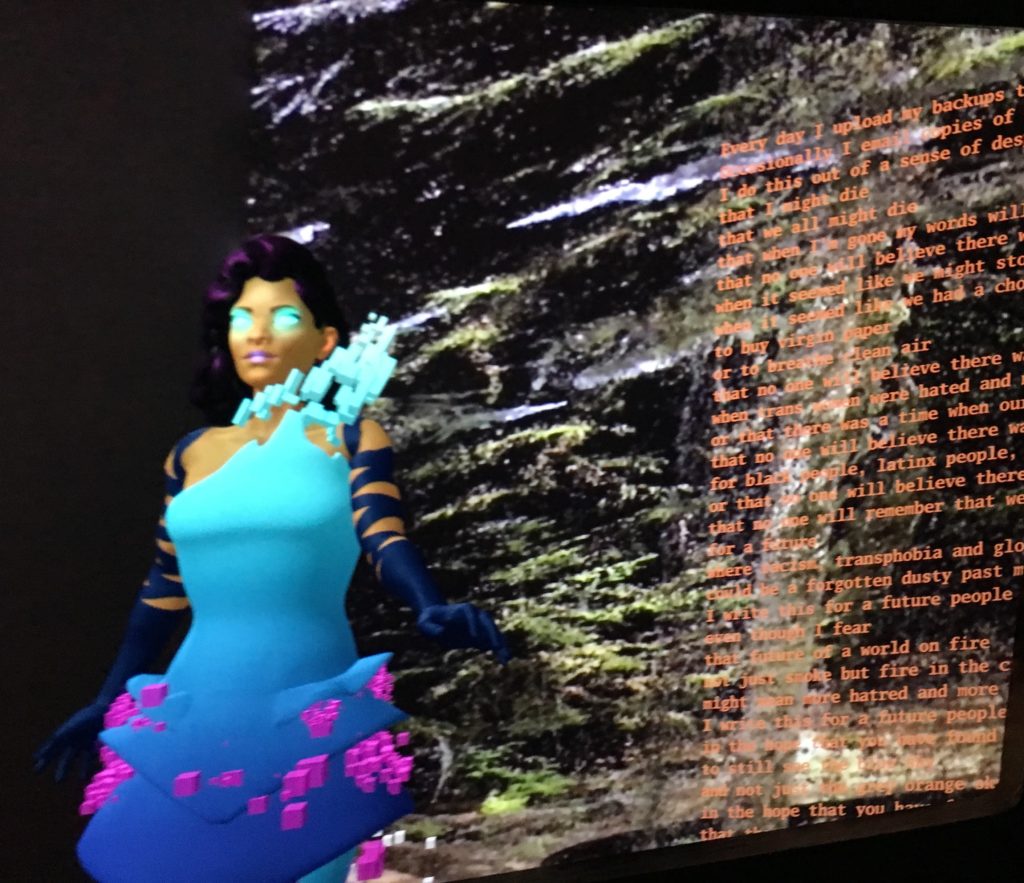

Sin Sol, Forest Memory by micha cárdenas and Abraham Avnisan immerses us in a forest landscape on three walls

Installation with multi-channel video composed from color LiDAR data scans (with sound; duration 5 hours), augmented reality poetry, and 3-D avatar.

Courtesy of the artists.

Hanging in the center of the gallery ipads offer a conversation between Aura, a virtual reality ancestor from the future and a present person who recites poems about the impact of living in a smoke filled landscape: “No trees, no horizons all gray. People like me need to stay inside. It’s been weeks.;” “I fear the future of a world on fire, not just smoke but fire might mean more hate.” I found these poems almost desperately sad especially now that we have had the season of wild fires in Australia, it is all the more believable.

Multi-media installation with mirror columns, specimens cast in resin, CGI animations (color, with sound), and HD video (color, with sound; duration: 7:14 minutes).

Courtesy of the artist and Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary Collection, Vienna.

Susanne Winterling’s Glistening Troubles animates resin replicas of bioluminescent single cell organisms on individual monitors. We feel we are underwater with them in a fragile environment that periodically vanishes as the screens go blank. An interview with a fisherman/guide suggests that historically these glowing creatures were seen as magical because they made the water glow, today they are valued for healing properties. Dependent on salt water, they respond to movement both human and natural. Too much fresh water stimulates them to retreat into the depths. Winterling emphasizes communication among these organisms and the natural environment, as well as our ability to disrupt or poison them with toxins.

Video installation (color, with sound); duration: 18:50 minutes.

Courtesy of the artist.

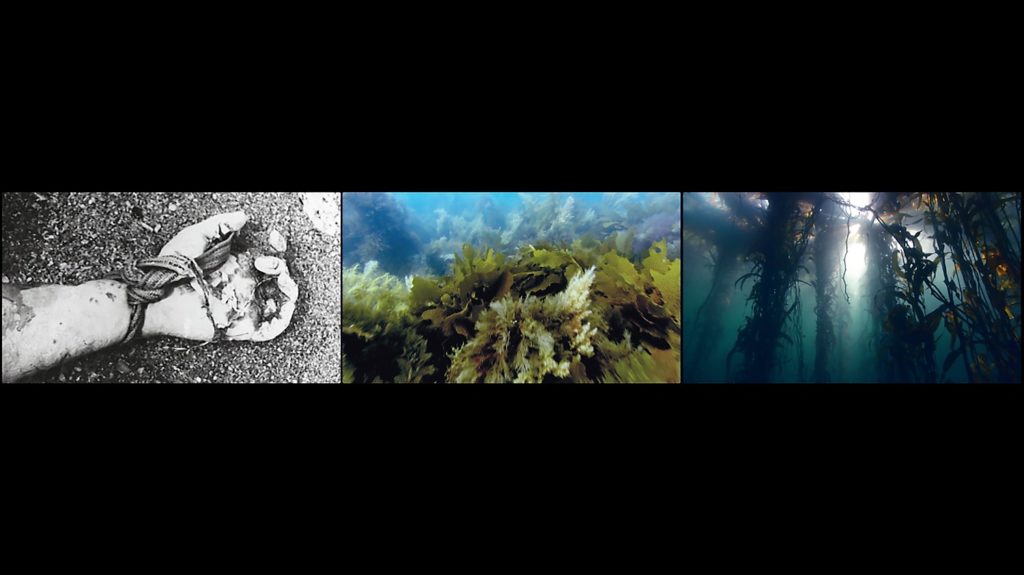

Finally, Acoustic Ocean by the internationally renowned ecological artist, Ursula Biemann, connects us to deep sea sounds. Ironically first heard as a result of a military project, the sonar communications again refer to interspecies communication, particularly whales. Sofia Jannok, singer, environmental activist, and indigenous Sami speaks of the impact of changing climates on her community. She then insets listening devices into the sea of a desolate arctic landscape and listens to the sounds of the deep Arctic sea.

“Between Bodies” demanded time to embrace these alternative ways of experiencing the natural world, but it also offered possibilities for a future beyond confrontation and aggression. Taking another deep breath of Hormonal Fog on the way out reinforced that. ( written for Sculpture magazine, but never published so here it is free for nothing)

Added March 2020: We especially need that hormonal fog with our current global crises, hugely aggravated in the US by incompetence at the top ( some people say a deliberate strategy to wipe out the low income wage earners and replace them with robots and digital technology) . Viruses are not directly addressed in these works, but the interconnections of technology, human and nature is profoundly important to us at this moment. These artists are offering a new way to think about that.

This entry was posted on March 14, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.

John Akomfrah!

John Akomfrah’s “Future History” (until May 3, 2020) majestically fills three major galleries on the fourth floor of the Seattle Art Museum with video works projected on huge walls in separate darkened rooms.

Brilliantly curated by Pamela McClusky, Curator of African and Oceanic Art, the three works span 500 years of history from the beginning of the slave trade in Elizabethan England to the present moment. Each work is immersive and mesmerizing. You will not be able to stop watching them. As McClusky pointed out, the experience is the opposite of racing through a gallery and giving 30 seconds to each work. Here we watch for up to 45 minutes.

Three channel HD colour video installation, 7.1 sound,48 minutes 30 seconds

We first encounter Vertigo Sea of 2015. In this photograph we see Olaudah Equiano. Thanks to Pamela, we have what are known as “footnotes” for the exhibition, individual sheets we can take home. I had never heard of Olaudah Equiano, but he is monumentally important in the history of slavery. Here we see a man dressed in the typical garb of the eighteenth century gentleman. Looking closely you can see he is dark skinned. He appears to be brooding in a desolate Arctic landscape.

Equiano wrote an autobiography published in 1789 that describes his personal experience from being captured by slavers when he was eight, taken to Virginia, London and West Indies, but finally buying his freedom in 1766. He then began collecting and recording whale and polar bear killings. He overturned the cliché of Africa as a place of barbarism, and describes instead his home as “idyllic. with strong leaders, varied foods and festivals, and defined sense of order. This memory is contrasted with vivid descriptions of slave traders as cruel and barbaric; of suffocating sweat, smells and traumas on ships crossing the Atlantic and the humiliations he endured and and witnessed in the slave trade around the world. ” Equiano led the abolition movement in England and his autobiography is said to have contributed to the success in abolishing slavery in England and the British Colonies ( although not the huge financial benefits of the trade).

Projected as three large adjacent images, Vertigo Sea overwhelms us. Sometimes the images flow from one to another, other times they sharply clash. If you have ever seen one of David Attenborough’s BBC nature films, you will recognize some of his incredible footage: the artist gained permission to use it after befriending Attenborough for a full year. But Akomfrah goes the extra step that Attenborough only touches on in his most recent film: climate crises caused by our own actions.

He juxtaposes stunning nature sequences with the murder of humans in the slave trade and the hunting of whales. We watch horrified as the spears enter the animal and the helpless whale bleeds into the sea and dies, even as another screen celebrates their beauty. We gasp in disbelief at the reenactment of slaves forced overboard alive. Akomfrah gives us the unrelenting brutalities of genocide by hunters of animals and people who shared a single minded goal – to make money. Interspersed in the film are many quotes including Moby Dick and Heathcote Williams 1988 poem Whale Nation:

“From space, the planet is blue/ From space the planet is the territory/Not of humans/ but of the whale.”

Occasionally the sequences take a breath with three blank blue screens. But you will not be able to stop watching.

Akomfrah spoke of the flux and fluidity of water as suggesting the past, present and future. Our bodies are 90 percent water. But rather than acknowledge our connection to the sea, the planet, and its occupants, he stated, our hyper consumerism is destroying it.

I heard Akomfrah speak in a conversation with D.J. Spooky at the museum (right before all programming shut down because of the THE VIRUS). He met DJ Spooky while he was making The Angel of History in 1995.

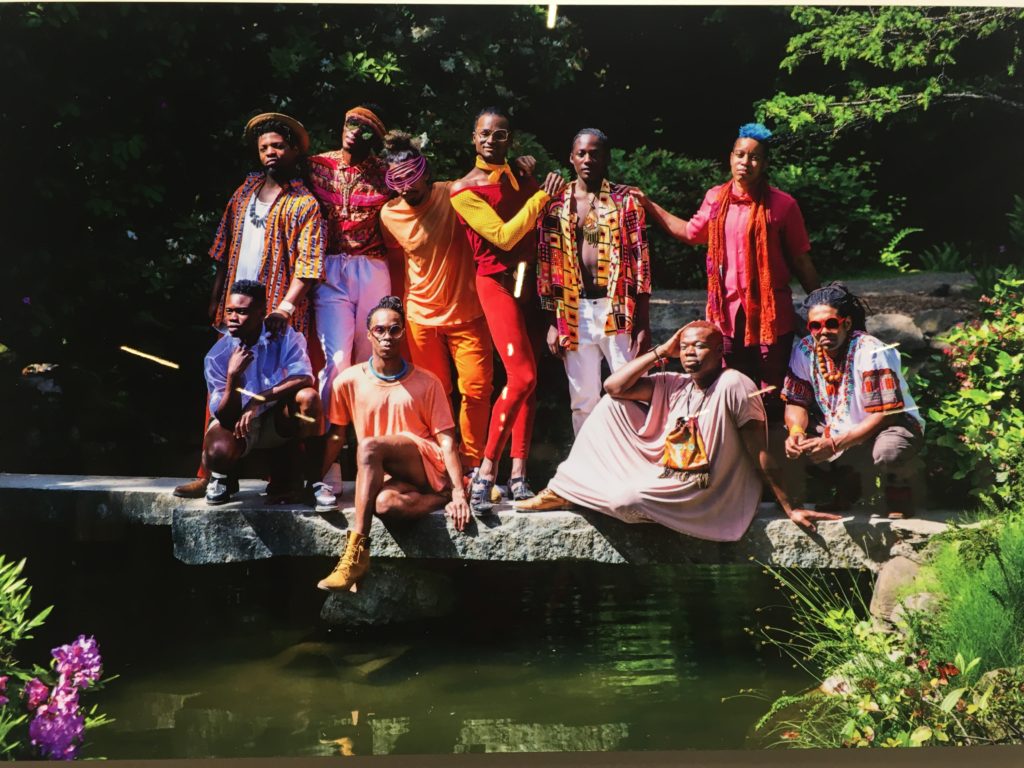

Angel gives us Afro- Futurism: musicians, writers, poets, actors, journalists, philosophers and techies. Afro-Futuriam, is described by the brilliant writer and musician Greg Tate “It’s like a beautiful compendium of the cats who were obsessed with what I call the “imagineering” of ideas—putting Black folks in a science fiction setting, in the future, or in the retro-future, listening back to ancient African kingdoms as a kind of science fiction fodder.” (Capitol Bop , interview 2015).

Note carefully that reference to African kingdoms, which also connects to cosmology and African mysticism. The musician Sun Ra is a major figure in these connections. He claimed to actually be an alien himself.

Seventeen creative thinkers, ranging from the cosmic musician Sun Ra to Nichelle Nichols, Star Trek actress, spin off Tate’s idea that “all those things that you read about- alien abduction and genetic transformation- they already happened. How much more alien do you think it gets than slavery, than entire mass populations moved and genetically altered, forcibly dematerialized?” (quoted by Kodwo Eshun). Tate died last fall at the young age of 60.

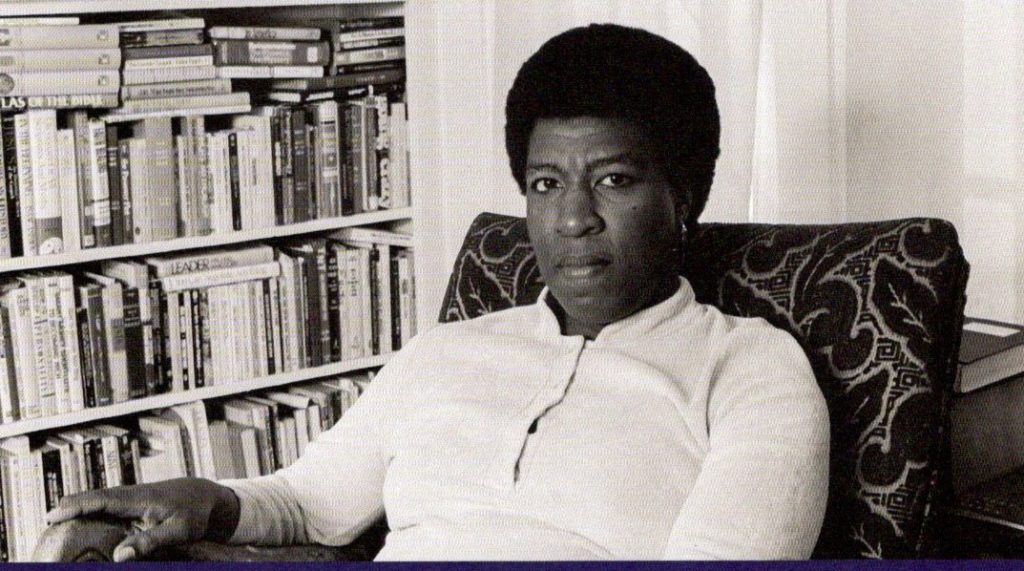

selected scenes: Data Thief

One of the compelling speakers was Octavia Butler, the only time she was recorded before her premature death in 2006. She wrote the Parable of the Sower in 1993 which predicts pretty much where we are today.

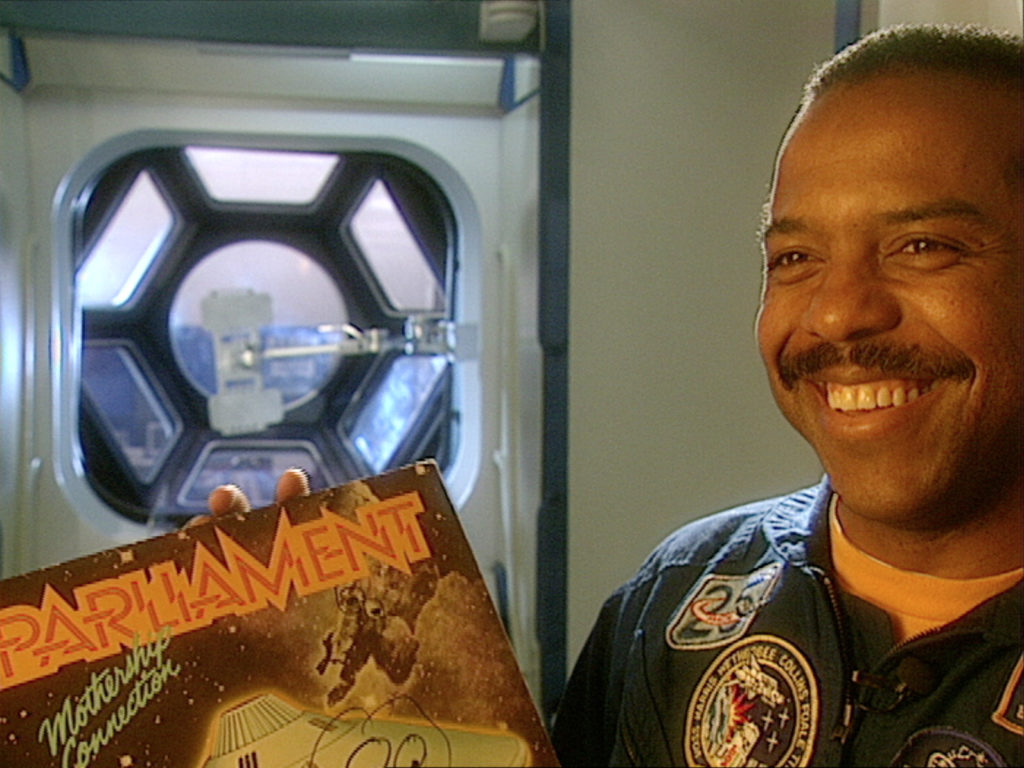

Another revealing person is Dr. Bernard A. Harris, Jr, the first African American astronaut to walk in space.

The third piece Tropikos 2016 silently and chillingly presents the historical roots of the slave trade in Plymouth, England, the major slave trading port during the reign of Queen Elizabeth. Here Akomfrah quotes from Paradise Lost, and The Tempest. He segues from images of the royal family and its pirates, decked out in the riches from the slave trade, to a silent raft moving up the river Tamar.

The raft holds one slave with his back to us as well as potatoes, pineapples, bananas, an 18th century metal helmet, and a sculpture of Akuaba associated with childbirth in Ghana. At the entrance of the exhibition is another Akuaba, from the Dogon people of Mali who holds her hands up in supplication for water.

According to curator Pamela McClusky ” She holds her hands up to implore the blessings of nommo, the master of water, who provides rain when it is needed. The Dogon have a saying, “people can’t stand and pray all day, but the sculpture can”.

Right now that seems like a place where we all are, imploring the blessings of the gods, in our case to help us work together to survive this crazy situation that our government brought on us because of their incompetence and stupidity in refusing test kits from the WHO in early February and closing down the CDC area responsible for planning for pandemics.

This entry was posted on March 13, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Hiawatha D, Christopher Shaw at the Northwest African American Museum, King Street again and the Henry Art Gallery

For the winter season here is Betty Shabazz X (Malcolm X’s wife): “We can say ‘Peace on Earth’ We can sing about it, preach about it, or pray about it, but if we have not internalized the mythology to make it happen inside us, then it will not be.”

Betty Shabazz X is included in a dual portrait with Coretta Scott King as one work in the riveting exhibition by Hiawatha D. at the Northwest African American Museum. Iconic Black Women: Ain’t I A Woman? (until March 15) features famous Black women in sports, politics and culture. The exhibition begins with Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth and ends with Simone Bile, Olympic Gold Medalist. Paired with each portrait is a powerful quotation by each woman. Uniting all of the women is the idea that they succeeded against incredible odds and if you want to enough you can too.

For example, Simone Bile writes “I would say to always follow your dream. And dream big because my whole career, including any of the things that I’ve accomplished, I never thought in a million years that I would be here. So, it just proves that once you believe in yourself, and you put your mind to something, you can do it.”

The poets, performers politicians, and sports stars are all familiar names: Maya Angelou, Nina Simone, Oprah, Toni Morrison, Coretta Scott King, Betty Shabazz X, Angela Davis, Serena Williams, Lupita, Maxine Waters, Shirley Chisolm, Michelle Obama and her daughters.

Across one wall are the young victims from the Birmingham Church bombings, and across another long wall, the Ain’t I A Woman series of six works on Black women in general as survivors and providers, and truth tellers. Almost all of the paintings focus on posture, gesture and clothes to identify these famous women; only a few of them include feet, hands and facial features.

At first that is disconcerting, but Hiawatha D’s simplified spatial relationships and abstract blocks of color set off the figures so effectively that we see the personality and power of each woman. We know them immediately. The absence of those details strengthens their presence and makes them more universal. The addition of potent quotations enriches our experience.

A second exhibition at the Northwest African American Museum by Christopher Shaw called Algorithm: Archetype is harder to explain, but easy to appreciate.

Here is a quote from the artist “…at the root of the concept for Algorithm: Archetype is an understanding that the way which we participate and propagate culture is based on systems of energy exchange… Archetypes exist in narrative and myth. Often these forms define the parameters of the space where knowledge exists. We have it within our power to shape, reject or recreate or own archetypes. In so doing, we can claim sovereignty over our own lives and cultures. We can rewrite the sequences that code our futures.” You probably need to read that again.

As you can see Christopher is an advanced thinker! He is a mathematician, engineer and clay artist. But when you see his work, you don’t feel overwhelmed by those abstract ideas, but by the beauty of his works. The installation of the minimalist clay and mixed media works is subtle, with several groupings of repeated shapes. Their unexpected relationships lead to meditation.

The Arts at King Street Station is once again offering an extravaganza in their beautiful big space. Brighter Future…to be heard, to be seen, to be free, organized through the City Hall collective Ethnic Heritage Art Gallery (until January 11), includes over fifty artists in all media. The show is an opportunity to experience a wide range of artists of color and discover new people. I was familiar with about five of them!! (Naomi is now an excellent Seattle Times columnist and an old friend.) But I was repeatedly excited by the work of a painter or sculptor or ceramist I had never seen before.

Shamim M. Momin, Senior Curator at the Henry Art Gallery filled the entire museum with In Plain Sight, (until April 26). Fourteen rising stars expose often invisible topics, communities, and stories.

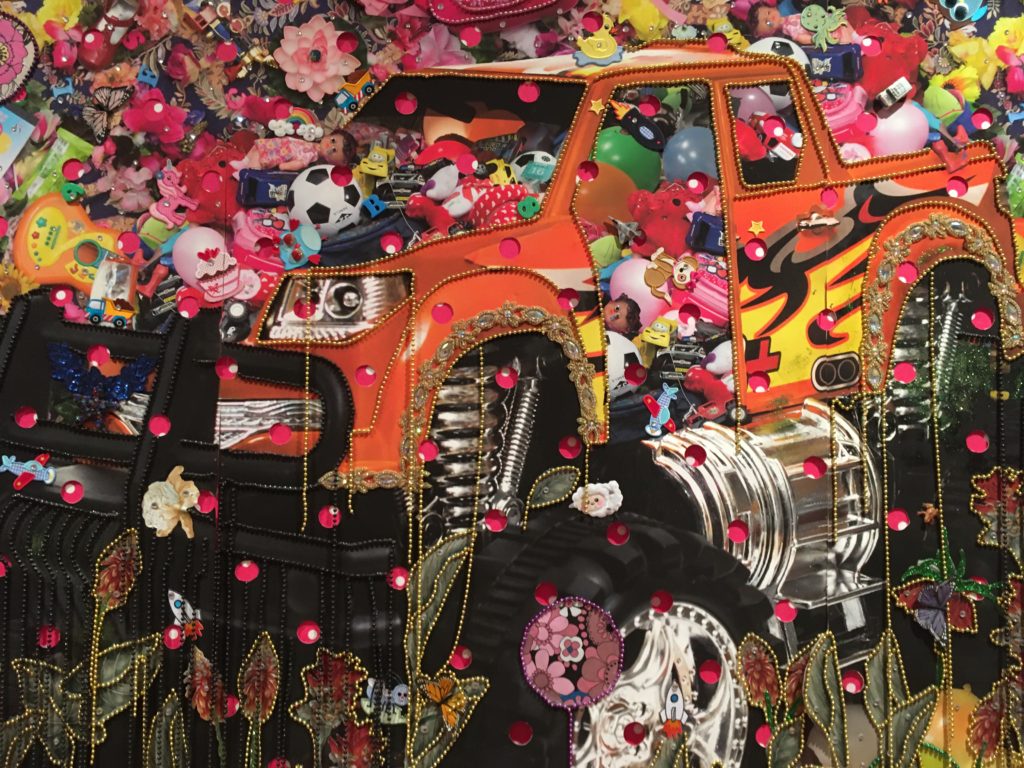

I loved Ebony Patterson’s ornamented coffins and stunning large-scale collages created in mourning and celebration of black youth who have been killed.

Exciting in an entirely different way is Oscar Tuazon’s Water School, examining water issues from the perspective of the past, present and future with an emphasis on indigenous rights. Tom Burr’s installations, quietly written in corners, list the names of locations for gay men to meet up that he cut out of Spartacus, an International Gay Guide.

Finally, Nigerian-American artist Jite Agbro’s exhibition Deserving, (until February 26) at the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art features a stunning mixed media print installation. She draws on patterns and indigo colors from Nigerian traditions that are hundreds of years old, and like so much else on the planet under threat in our current world. On January 19 at 3pm Agbro had a conversation about her work at the museum: she spoke of coming to art serendipitously as an immigrant mostly trying to survive. But a young instructor ( now the well known Romson Bustillo) at the Pratt School in the Central District reached out to her as a child and encouraged her. Her path was not easy with no money or privilege to support her, but now she is a big success and receiving commissions.

This entry was posted on January 30, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Paula Stokes 1845 Memento Mori

Paula Stokes’s 1845 Memento Mori at Method Gallery featured a stunning “cairn” of one thousand eight hundred and forty-five hand blown glass potatoes. Each potato was sandblasted making it opaque, and each one was different.

Paula Stokes is a native of Ireland who came here in 1993, but she still feels the draw of her home country.

She created this cairn to honor the millions of people who died in the potato famine in Ireland which began in 1845 and continued for four years. A potato blight, a fungus like organism first appeared in August of 1845, perhaps brought into the country on ships from the US (!). It took out one half of the crop immediately, and continued to infest crops for the next seven years, killing three quarters of the potatoes. As it wiped out crops, people became starved. Millions died.

All of the Irish farmers were tenant farmers on land owned by British gentry. Those landowners had introduced the potato only one hundred years earlier as a monocrop. But shockingly, even at the height of the famine, landowners ordered food exported to the United Kingdom.

In Ireland the failure of the crops led to immense numbers of deaths. Survivors, unable to have a crop to sell, were evicted from their homes, sent to orphanages and workhouses, and massive public food kitchens. Workhouses provided a temporary solution, but funds ran out quickly. The response from the British government was entirely inadequate, leading to more suffering.

Widespread death and desperation led to huge migration to the United States, as well as other parts of the world. Orphaned girls were shipped to Australia. In the first four years one million people emigrated. By 1901 six million had emigrated.

The immigrants to the United States faced prejudice and racism, just as immigrants do today. Nativists attacked them. But in the long run they, like all immigrants here, have become part of our country and made many invaluable contributions.

Paula Stokes’ installation both honors the nightmare of the famine in Ireland, and creates an homage to the idea of community and caring. The creation of the piece required a team of assistants. The act of blowing into the glass suggests a life giving force. The installation becomes, as one writer in the catalog suggests, an echo of the landscape filled with ancient ruins from which the artist has come.

The installation is both beautiful and fragile. As we touched a glass potato and immersed ourselves in the installation, it is possible to think about both the deaths of those who relied on agriculture, and the lives of those who survived.

The ownership of the land by the ruling classes in England led directly to destitution for the farmers who were their tenants, when the crops failed. Today migration has similar underlying causes in the exploitation of the poor by the wealthy. Now the wealthy are corporations destroying indigenous lands to build dams and extract oil in Central America. In Africa, droughts, war, greed and poverty lead to migration.

As people today are driven from their homes by famine and violence, both caused or aggravated by the climate crises, it is crucial to remember the underlying economic forces of the disastrous famine that drove Irish migration of the late nineteenth century.

But unlike the nineteenth century, when the millions of Irish could enter the US or Europe easily, the immigrants today who do not die or drown are almost entirely delayed, detained, and locked up. Traditional procedures for entry are rapidly being dismantled by racist governments.

Thank you Paula Stokes for your meaningful work. We need more “Memento Mori” for our current world wide crisis.

This entry was posted on December 10, 2019 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Donald Byrd Choreographer

“Dance as Provocation”

Part I “Donald Byrd: The America That Is To Be” at the Frye

Art Museum, October 12 – January 26.

Susan Noyes Platt www.artandpolitics.com

Donald Byrd transforms movement into resonant art. The world-renowned choreographer Donald Bryd has been based here in Seattle since 2002. In March 2016, I wrote here about his humble base in the Madrona Bath house.

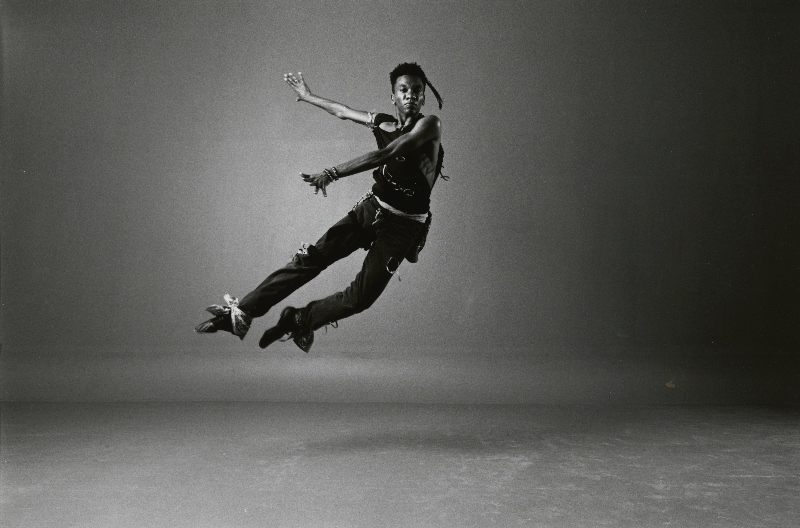

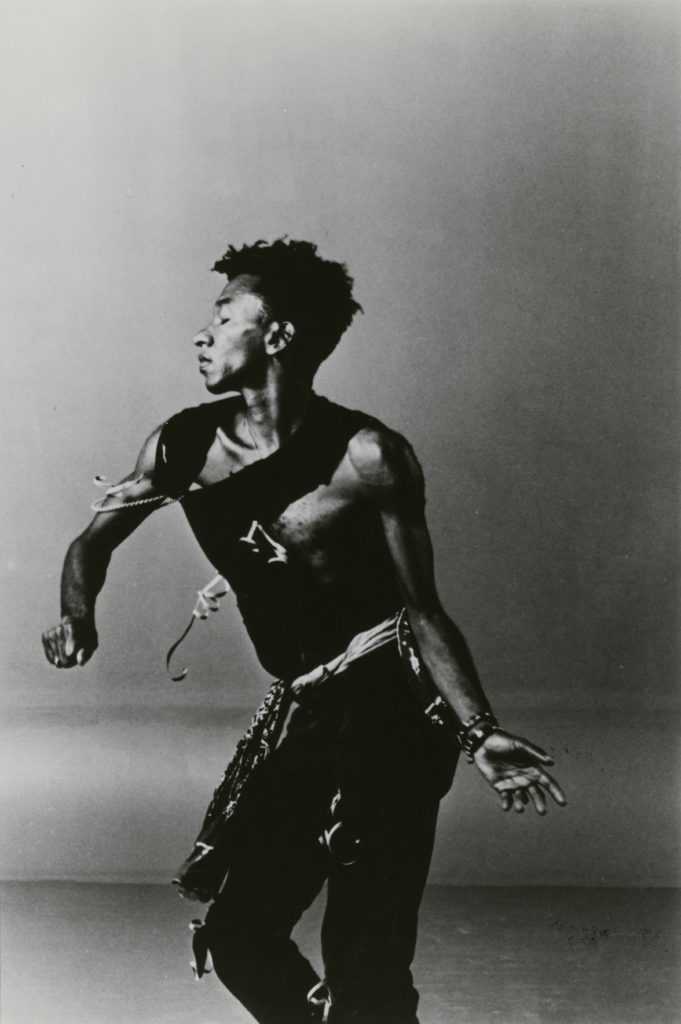

A groundbreaking retrospective of Donald Byrd’s career, curated by Thomas F. DeFrantz, Professor of Dance, Duke University, successfully overcomes the challenge of exhibiting dance in a venue designed for visual art. Videos from the 1970s to the present (from tiny to huge), as well as photographs from throughout Bryd’s astonishing career, mesmerize us as we witness his extraordinary creativity. In addition, on a low stage inside the gallery we can enjoy intimate performances by the Spectrum Dancers on Tuesday and Wednesday at noon and Saturday and Sunday at 3PM.

Donald Byrd has been radical from his first performances in Los Angeles as early as 1978, when he challenged racism, gender, and bourgeois sensibilities with a classical pas de deux that paired a “disaffected” black man and “blasé cigarette smoking” white woman. His choreography has deep classical roots, but he has consistently expanded the ways that he can confront us with deep social issues through music, movement, gesture, and settings. He deeply believes that dance can trigger social transformation.

His main inspirations are the giants of twentieth century dance George Balanchine, Merce Cunningham and Alvin Ailey, but he also explores popular traditions ranging from punk and funk to Irish jigs. His encyclopedic vocabulary of movement (as well as music) becomes his own as he embodies challenging social issues.

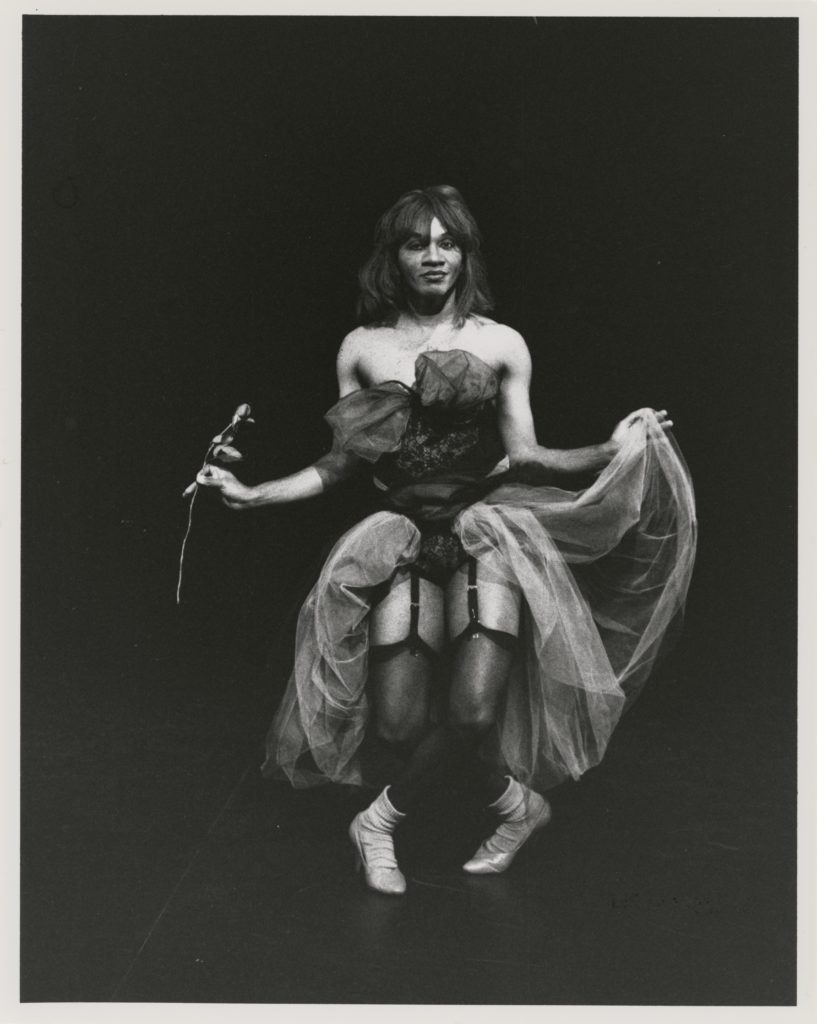

Earlier in his career he aimed to shock: we see him in beauty pageant drag, singing an exaggerated “God Bless America” in American Dream, 1995 in a performance that includes “a phantasmagoric patchwork of terror and display.” You will have to see it to know what this means!

In addition to confronting bourgeois race and gender clichés, Bryd rewrote classics. In his Harlem Nutcracker, 1997, Clara now an African American matriarch, welcomes her well-to-do family for Kwanzaa and Christmas in Harlem. The choreography parodies traditional ballet while it also celebrates African American dance traditions. Another even bolder retelling is The Minstrel Show, Revisited, 2016: it confronts us with the ongoing existence of the racist blackface.

At the center of the exhibition at the Frye is a gallery with four large walls filled with A CRUEL NEW WORLD/the new normal, 2013. Performed in the orange jump suits worn by prisoners and detainees, and inside a hurricane fence, with an American Flag falling on the ground, it explores, through extreme movements, the anguish of being trapped with no way out.

Also included are excerpts from the WOKENESS festival last fall that featured intense performances by his extraordinary dancers on lynching and the killing of African American men.

Finally don’t miss Donald Byrd performing Sweltering Son only two years ago!

This entry was posted on and is filed under Uncategorized.

Preston Singletary and Raven Skyriver

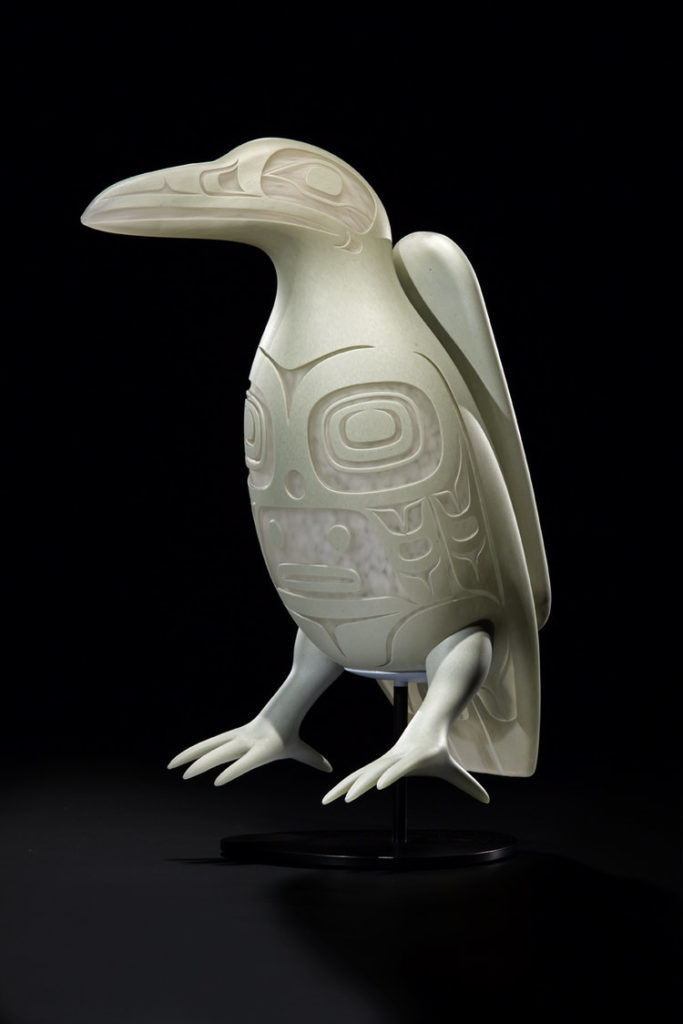

Preston Singletary (Tlingit, American) had a dazzling exhibition in Tacoma that recently closed called “Raven and the Box of Daylight.” The sculptures told the famous Raven story step by step with some full on installations, and special effects added in. We were mesmerized by the flow of the story and Preston’s presentation.

“Before here was here, Raven was only named Yeil

“He was a white bird and the world was in Darkness. Raven decides he will try and do something about the darkness, for himself and for the world. As he follows the Nass River, he encounters the Fishermen of the Night. . . . They tell Yeil Naas Shaak Aankaawu (the Nobleman at the Head of the Nass River), has many treasures in his Naa Kanidi (Clan House) including beautifully carved boxes that house the light.”

“Yeil(Raven) knows he will not be welcome in his raven form and devises a plan to transform himself to a tiny speck of dirt. His plan is to float down the river into the drinking ladle of the young woman, Naas Shaak Aankaawu du Seek’ ( Daughter of the Nobleman at the Head of the Nass River). That is how he will sneak into the Naa Kanidi( Clan House)

“Yeil turns himself into a piece of dirt and falls into the water. He floats into the young woman’s ladle as she dips it into the river for a drink. …

“Yeil is ingested by Naas Shaak Aankaawu du Seek’ and she becomes pregnant with Yeil.”

“Yeil grows into a precocious and precious human boy. “

The center of the exhibition was the clan house with its prized possessions, the stars, the moon and the daylight. Through pleading with his grandfather, who adores him, Raven is able to liberate the box of the stars, moon and daylight.

“As the stars fill the sky and as the moon takes its place. light begins to fill the earth. When the sun takes its place in the sky, bringing daylight to the world, it is frightening to all those who have been in darkness. The people are able to see the world around them for the first time and are startled. Those wearing animal regalia run to the woods and become animal people, Those wearing bird regalia jump in the sky and become The Winged People. Those wearing water animal regalia become the Water People. Those who remained strong (and stubborn) became the Human People.”

“Yeil decides it is time to leave and transforms back into bird form. Naas Shaak Aankaawu ( Nobleman at the Head of the Nass River) is devastated that his treasures have been released into the sky. He is so angry that he gathers all the pitch in the Naa Kahidi ( Clan House) in a bentwood box and throws it into the fire. He catches Yeil as he tries to escape out of the smoke hole and holds onto his feel Yeil is covered in the soot and smoke of the fire. He is transformed from a spiritual being tin the black bird we know today. His color marks his sacrifice. His physical form is forever changed for bringing light into the world”

At the same time as this exhibition, we enjoyed musical performance by both traditional Alaskan Tlingit Kuteeyaa and Preston Singeltary’s band Khu eex’. I can’t seem to us load the video here.

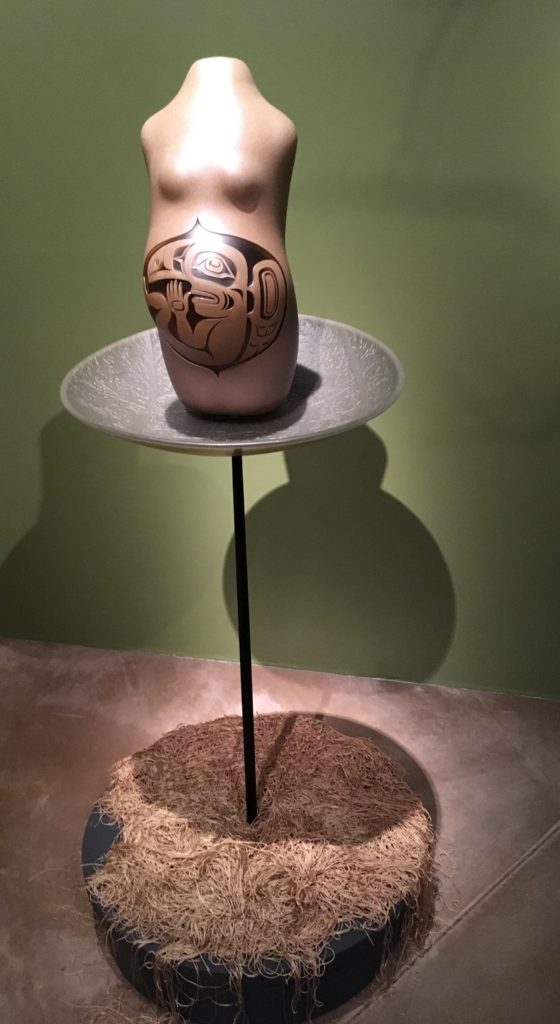

If you missed this special exhibition at the Museum of Glass you can still see Preston’s work as well as that of Raven Skyriver at the Stonington Gallery this month. Also on exhibit is his mentor Joe David. Raven Skyriver and Preston spoke at a panel this summer at the Museum of Glass where they spoke about the importance of the hot shop there for expanding the possiblities of their work in glass. Raven Skyriver who is from Lopez Island compared fluid glass to the marine environment. He sees himself as “perpetuating culture in glass.” Historically house leaders commissioned art. It has to be commercial now. His work presents endangered sea creatures. threatened by acidification, overfishing, and pollution.

Preston spoke of beginning his glass work only ten years ago. In the press release it emphasizes that he spent years studying form line design in order to create glass in the Tlingit tradition. He has studied with some of the great artists of contemporary Native Art. We all know how stunning his work has been in that medium. His glass work has transformed my point of view on glass sculpture. Last summer, he and Raven Skyriver collaborated on work for the first time. And this exhibition is in honor of that collaboration. Carefully note in the captions all the different techniques for working with glass: hot sculpted, glass cast, blown, sandblasted, sand carved.

Blown and Sandblasted Glass | 36″h9″w9.5″d

Blown and Sandblasted Glass | 14″h11″w11″d right Preston Singletary Sun Medallion Open Edition Cast and Frosted Glass

7″h7″w1″d

This entry was posted on October 4, 2019 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Natalie Ball Betty Bowen Award Winner at the Seattle Art Museum

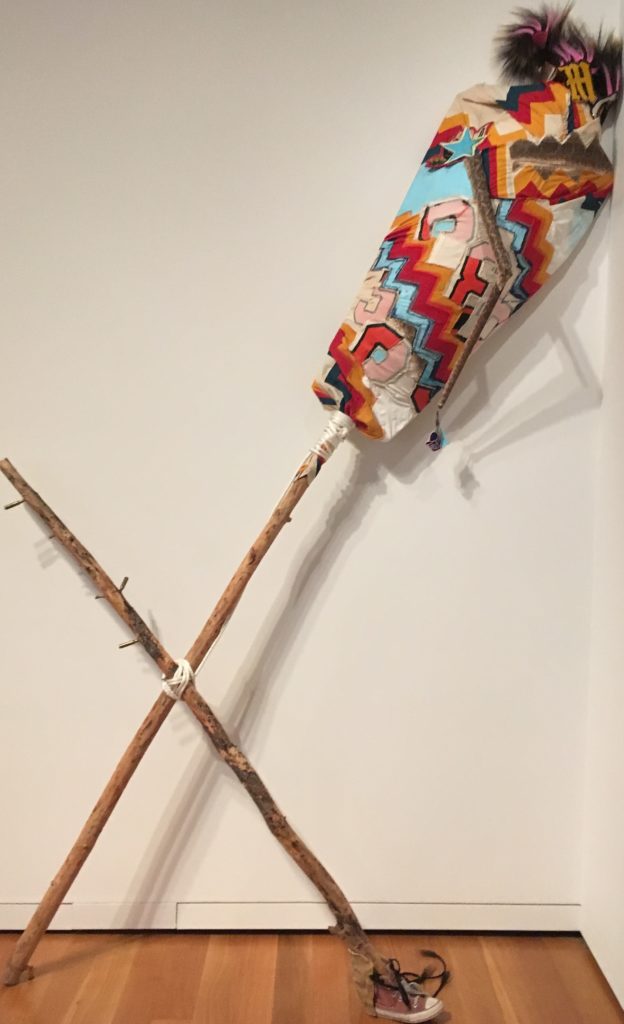

The Betty Bowen award winner Natalie Ball (Modoc, Klamath) has installed a provocative pair of works in the Seattle Art Museum . Ball is descended from the famous leader of the late nineteenth century Modoc resistance, Captain Jack. That heritage of warrior defiance is obvious here.

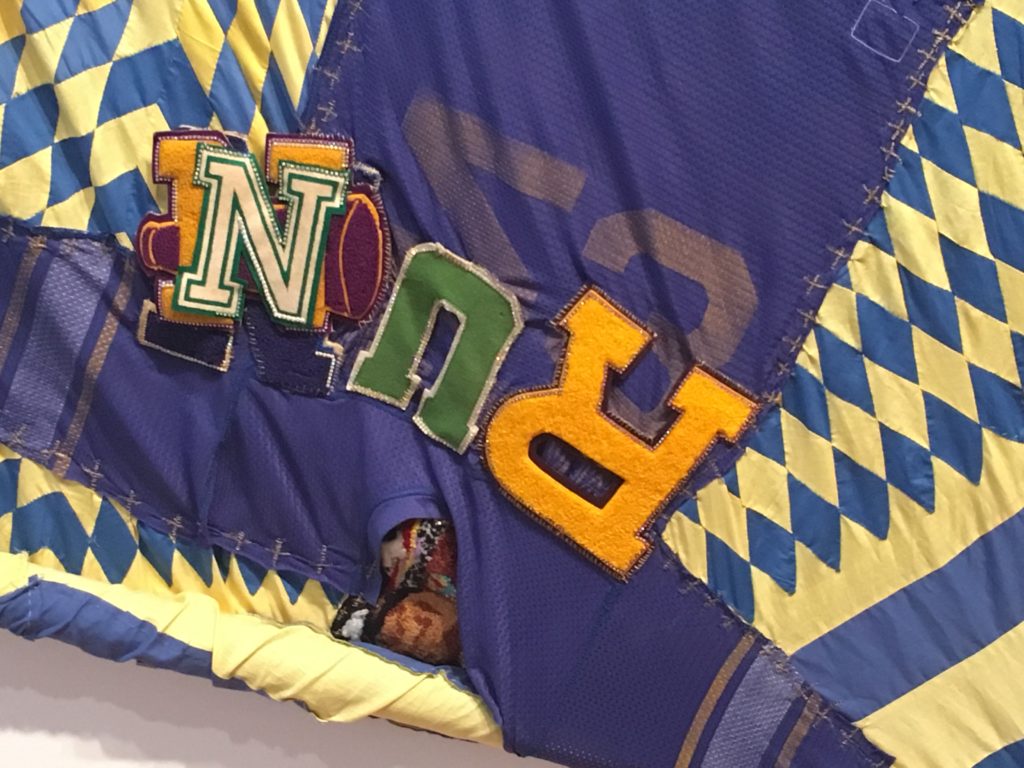

You Mist, again (Rattle) and Re Run make up the installation “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Snake.” The title interrupts the familiar nursery rhyme about the stars with a snake that can be both threatening and magical. Ball explores the collision of indigenous and white cultures as well as African American, also part of her heritage

One of the unintended juxtapositions of the installation is the view of the Marsden Hartley in the next gallery. Hartley’s work suggests his affinity with Native American patterns, although he did not move to New Mexico until later. Scholars traditionally focus on the references to Berlin in his symbolism, but seeing his work next to Ball’s the connection is unmistakable.

Detail You Mist, again (Rattle) of

at Seattle Art Museum,

photo: Susan Platt

at Seattle Art Museum,

photo: Susan Platt

Detail You Mist, again (Rattle) of

at Seattle Art Museum,

photo:Lauren Farris.

You Mist, again (Rattle) is full of mysterious references and startling juxtapositions. Ball’s work frequently suggests collage with extremely disparate elements. She purposefully mixes pop, elite, folk, mystical, and humor, along with her sophisticated command of color and composition, to keep us guessing. Looking closely we see crazy pink hair at the top, what she describes as braiding hair, as well as deer and porcupine hair. In that detail alone, the cross referencing of the natural world and the cultural world suggests her willingness to defy any accepted parameters. Even the over all idea of the rattle, here on a huge scale, is in our face, and somewhat frightening.

Note also the bullet shells embedded in a stick supporting the giant rattle. And what about that crazy unlaced shoe and the beaded blue rose hanging from the end of the snake skin. Trickster humor is juxtaposed here with celebrating indigenous vitality and perhaps some crazy sarcasm.

at Seattle Art Museum,

photo:Lauren Farris.

Detail You Mist, again (Rattle) of

at Seattle Art Museum,

photo:Lauren Farris.

Natalie Ball, Re-Run, 2019

Cotton, crystals, pine, chenille, polyester, rattle snake, canvas, acrylic, and leather

Photo by Natali Wiseman

Rattlesnake skin appears as part of both works (although significantly identified simply as rattlesnake), a skin that a snake has shed, after it regrows another, a clear reference to the survival abilities of indigenous peoples, in spite of white man’s best efforts to obliterate them.

The second work Re-Run, is a tilted construction created from a diamond patterned quilt. That pattern is joyful, but the words “Run” and “Ran” formed from overlapped sports letters and mascot imagery suggest a different mood entirely and violently interrupt any easy reading. But the larger figure at the center of Re-Run suggests a tricky, but successful balancing act, that can refer to life in general. There are so many possibilities here for metaphors, that I suggest that you take a good long look and think about it. (Until November 17).

Just for fun I will end with Natalie Ball’s work in YƏHAW̓! the fabulous contemporary indigenous show this summer that I wrote about in early May. She showed another amusing, defiant work which is untitled. But juxtaposing a red tutu and hair weaves with a woven basket is outrageous enough without a title.

This entry was posted on September 24, 2019 and is filed under Uncategorized.

South African superstar photographer Zanele Muholi at the Seattle Art Museum

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

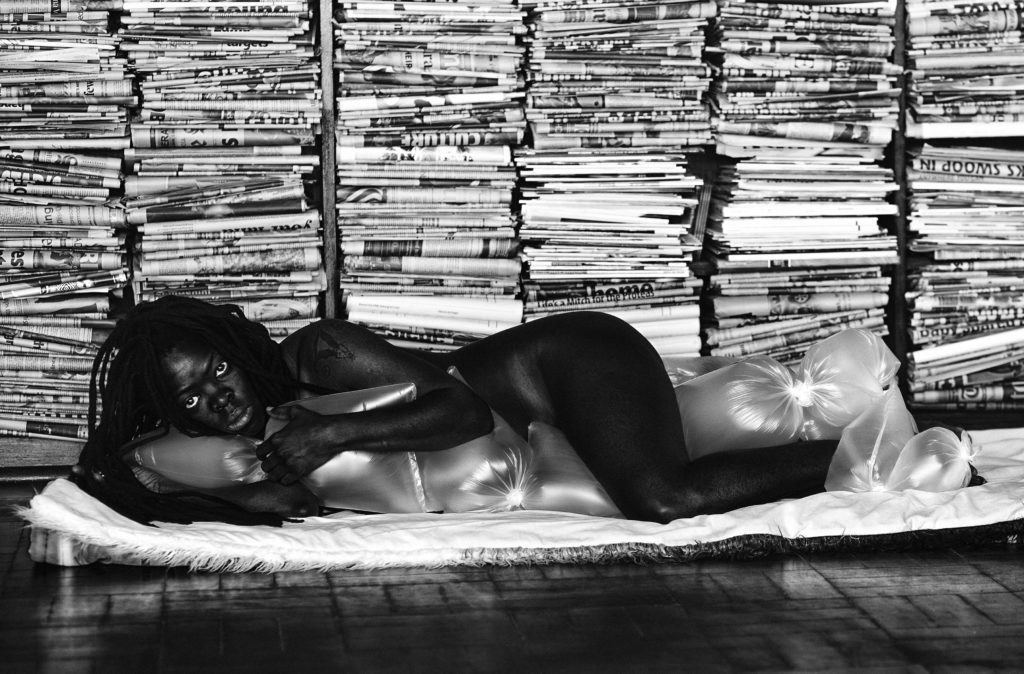

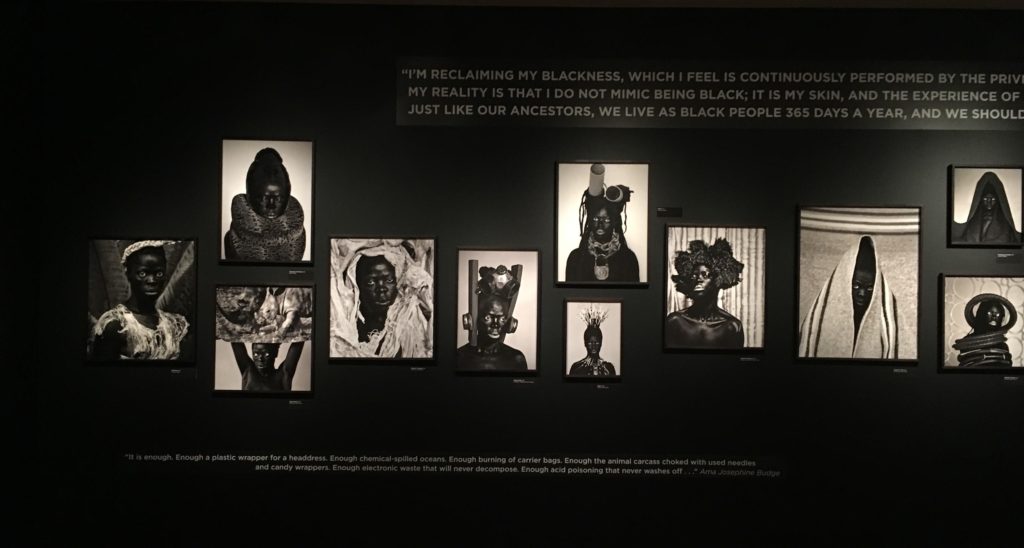

Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness

South African superstar artist Zanele Muholi bursts out of the Jacob Lawrence and Gwen Knight corner gallery at the Seattle Art Museum: “I’m reclaiming my blackness.” Their exhibition “Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness,” spills into four adjoining spaces.

First, we see the huge signature self-portrait visible from several galleries away, invading our experience of the work of mild white men in adjacent galleries. The artist wears a headdress of sheepskin that takes a lion’s mane to the next level of luxuriance. Keeping in mind that it is the male lion that has a mane, this lioness identifies as they. They look to the side, focusing beyond us.

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape

Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

Turning around, we see the artist posing in a mural scaled photograph in what evokes a classical reclining nude posture, until we realize that it contradicts that tradition of exploitation. Lying on their side and holding tightly to multiple plastic pillows that cover all specifically sexual body parts, they displace and occupy the reclining nude tradition constructed for male eyes throughout art history.

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape

Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

Moving into the next space, another 4-foot self-portrait evokes the statue of liberty, with the crown replaced by large coils of black foam and the gaze directed skyward. Again, the icon is redefined, reoccupied, remythologized. As “liberty” has become an empty word, this upward gaze expresses that impatience and absurdity.

The oblique gazes accent the whites of the eyes in every image in the show. As we enter the main gallery, painted entirely in black on two walls, we experience these intense looks over and over, trapped as though by pincers on four walls of self-portraits. In each work the artist transforms into a goddess, a miner, a queen, a king, and even a rocky cliff or forest. The artist collects found materials from various places: buying from stores, clothing from friends, items found in hotels or friends houses. The props enable layers of metaphors and political references that range from historical to contemporary, from personal to public

.

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

For example, in a self-portrait with South African money pinned to their head, a cow’s skin pinned on their shoulders, the references can be to the “bride price,” the selling of woman like cattle, but defiance and resistance embodies the posture and the gaze, even as it seems to suggest surrender.

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape

Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

In another work, an homage to her sister, a gentle and proud Muholi wears a crown and necklace of rubber inner tubes that confer majesty, and a defiant inversion of the violent history of rubber in Africa, where the Belgian King Leopold ruthlessly killed thousands to satisfy his thirst for that “natural” product. We can draw a straight line to the exploitation in the Congo today to obtain the minerals for our electronic gadget

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape

Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

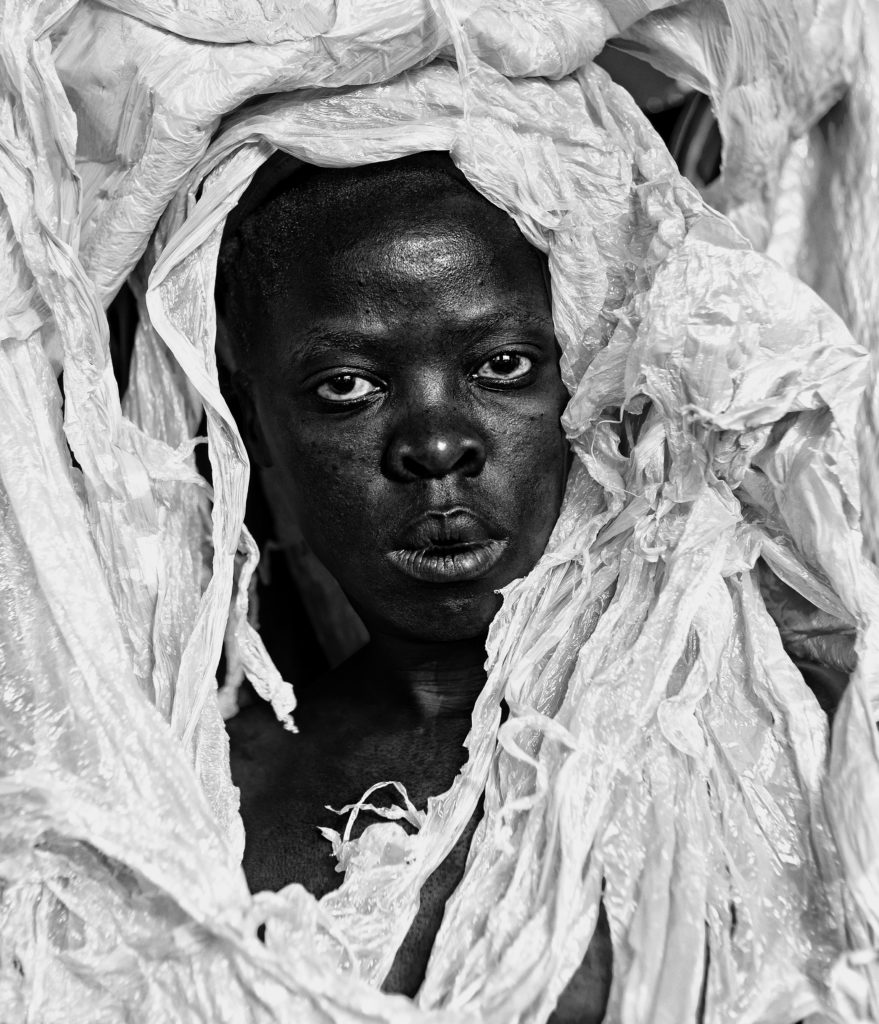

Every single image can be approached with layers of meanings, as brought out by the intense and indispensable series of essays in the catalog. About the portrait “Kwanele, Parktown 2016 it is enough,” a face surrounded by plastic detritus, Ama Josephine Budge writes:

“Enough a plastic wrapper for a headdress. Enough chemical spilled oceans. Enough burning of carrier bags. Enough the animal carcass choked with used needles and candy wrappers. Enough electronic waste that will never decompose. Enough acid poisoning that never washes off. Enough villages under sand. Enough sand stolen for cement. Enough salinized cropland. Enough desertification. Enough brown bodies on the shoreline. Enough plastic wrappers forced migration. Enough polyethylene saran-wrapped suitcases—everything I could grab in a moment—abandoned at the immigration centre. Enough tear gas in the eyes of protestors. Enough extinct species. Enough plastic-strewn beaches. Enough. Enough. Enough. Enough. Enough. How many times must I say, ‘kwanele’ it’s enough, before what you hear is not more but too much.”

The directness of the artist’s bold head shots controls us as we look back seeing the steely gaze, the power, the anger, the courage. Muholi speaks of occupying public space, the spaces given to white people. As a South African, Muholi is particularly aware of the segregation of public space and its history in apartheid, but the entire planet is rapidly becoming an apartheid state with migrants imprisoned at militarized borders or drowned at sea.

Prior to this series, Muholi in an ongoing series photographs the LGBTQIA people of South Africa in a series with the title Face and Phases . They are honoring those murdered and those living amid murders and crimes against their community. Their own studio was ransacked, and unprinted work deliberately destroyed.

Turning the camera back on their own face in these portraits, Muholi allows no objectification of the other, deliberately negating a long tradition of the black body in ethnography, anthropology, tourist and so called “documentary” photography. The body is Muholi’s, the narrative is Muholi’s.

The statement is both local and global: the artist has constructed the images all over the world and identified each image by city, and in isiZulu, their native tongue. Working in black and white (albeit with color film) is another political reference to photography as created by white eyes and cameras calibrated in F stops for white skins. Here the subtle tones of black emphasize the many nuances of dark skin colors.

We are caught in the web of these layered metaphors that defy the state of our present world with brilliant defiance. “Hail the Dark Lioness”! (until November 8).

Don’t miss the videos behind the “Lioness” and read the articulate catalog!

This entry was posted on September 23, 2019 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Feminism, Uncategorized.