South African superstar photographer Zanele Muholi at the Seattle Art Museum

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness

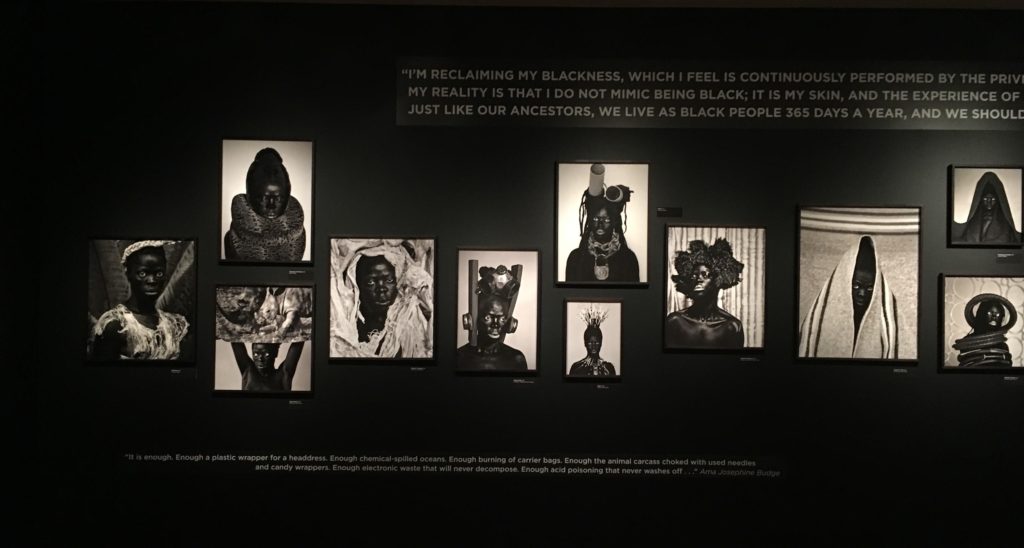

South African superstar artist Zanele Muholi bursts out of the Jacob Lawrence and Gwen Knight corner gallery at the Seattle Art Museum: “I’m reclaiming my blackness.” Their exhibition “Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness,” spills into four adjoining spaces.

First, we see the huge signature self-portrait visible from several galleries away, invading our experience of the work of mild white men in adjacent galleries. The artist wears a headdress of sheepskin that takes a lion’s mane to the next level of luxuriance. Keeping in mind that it is the male lion that has a mane, this lioness identifies as they. They look to the side, focusing beyond us.

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape

Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

Turning around, we see the artist posing in a mural scaled photograph in what evokes a classical reclining nude posture, until we realize that it contradicts that tradition of exploitation. Lying on their side and holding tightly to multiple plastic pillows that cover all specifically sexual body parts, they displace and occupy the reclining nude tradition constructed for male eyes throughout art history.

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape

Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

Moving into the next space, another 4-foot self-portrait evokes the statue of liberty, with the crown replaced by large coils of black foam and the gaze directed skyward. Again, the icon is redefined, reoccupied, remythologized. As “liberty” has become an empty word, this upward gaze expresses that impatience and absurdity.

The oblique gazes accent the whites of the eyes in every image in the show. As we enter the main gallery, painted entirely in black on two walls, we experience these intense looks over and over, trapped as though by pincers on four walls of self-portraits. In each work the artist transforms into a goddess, a miner, a queen, a king, and even a rocky cliff or forest. The artist collects found materials from various places: buying from stores, clothing from friends, items found in hotels or friends houses. The props enable layers of metaphors and political references that range from historical to contemporary, from personal to public

.

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

For example, in a self-portrait with South African money pinned to their head, a cow’s skin pinned on their shoulders, the references can be to the “bride price,” the selling of woman like cattle, but defiance and resistance embodies the posture and the gaze, even as it seems to suggest surrender.

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape

Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

In another work, an homage to her sister, a gentle and proud Muholi wears a crown and necklace of rubber inner tubes that confer majesty, and a defiant inversion of the violent history of rubber in Africa, where the Belgian King Leopold ruthlessly killed thousands to satisfy his thirst for that “natural” product. We can draw a straight line to the exploitation in the Congo today to obtain the minerals for our electronic gadget

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape

Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

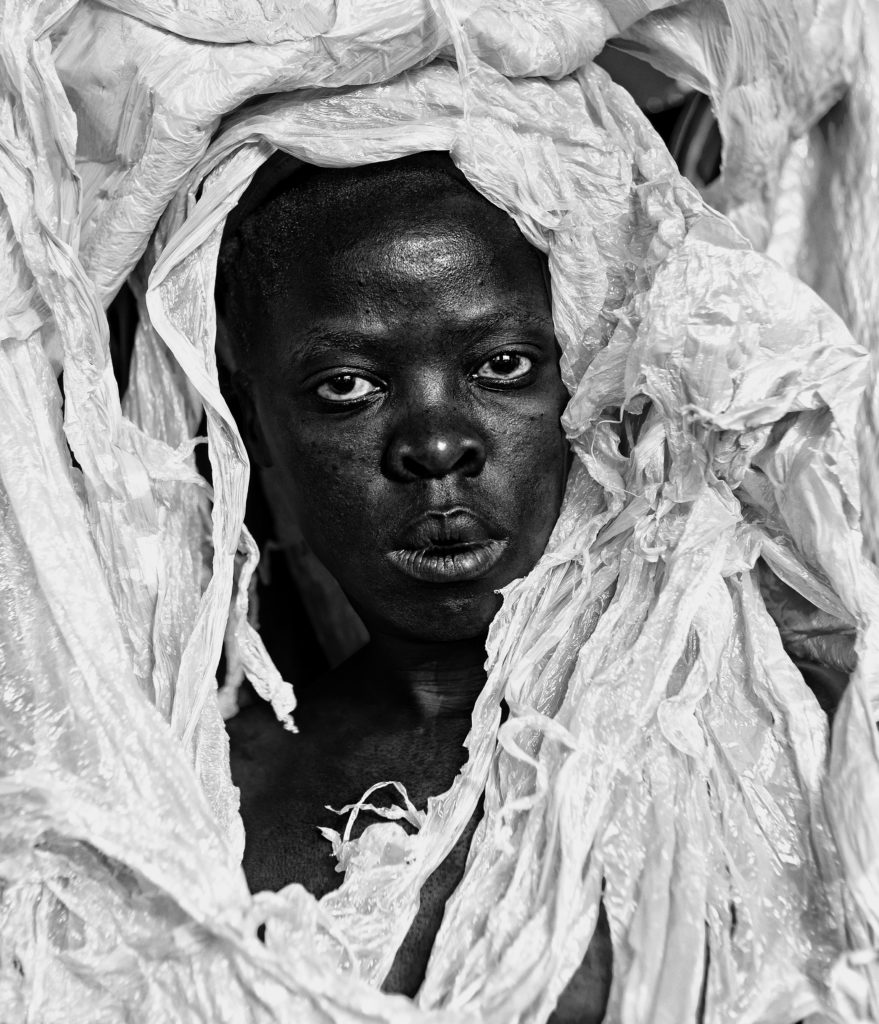

Every single image can be approached with layers of meanings, as brought out by the intense and indispensable series of essays in the catalog. About the portrait “Kwanele, Parktown 2016 it is enough,” a face surrounded by plastic detritus, Ama Josephine Budge writes:

“Enough a plastic wrapper for a headdress. Enough chemical spilled oceans. Enough burning of carrier bags. Enough the animal carcass choked with used needles and candy wrappers. Enough electronic waste that will never decompose. Enough acid poisoning that never washes off. Enough villages under sand. Enough sand stolen for cement. Enough salinized cropland. Enough desertification. Enough brown bodies on the shoreline. Enough plastic wrappers forced migration. Enough polyethylene saran-wrapped suitcases—everything I could grab in a moment—abandoned at the immigration centre. Enough tear gas in the eyes of protestors. Enough extinct species. Enough plastic-strewn beaches. Enough. Enough. Enough. Enough. Enough. How many times must I say, ‘kwanele’ it’s enough, before what you hear is not more but too much.”

The directness of the artist’s bold head shots controls us as we look back seeing the steely gaze, the power, the anger, the courage. Muholi speaks of occupying public space, the spaces given to white people. As a South African, Muholi is particularly aware of the segregation of public space and its history in apartheid, but the entire planet is rapidly becoming an apartheid state with migrants imprisoned at militarized borders or drowned at sea.

Prior to this series, Muholi in an ongoing series photographs the LGBTQIA people of South Africa in a series with the title Face and Phases . They are honoring those murdered and those living amid murders and crimes against their community. Their own studio was ransacked, and unprinted work deliberately destroyed.

Turning the camera back on their own face in these portraits, Muholi allows no objectification of the other, deliberately negating a long tradition of the black body in ethnography, anthropology, tourist and so called “documentary” photography. The body is Muholi’s, the narrative is Muholi’s.

The statement is both local and global: the artist has constructed the images all over the world and identified each image by city, and in isiZulu, their native tongue. Working in black and white (albeit with color film) is another political reference to photography as created by white eyes and cameras calibrated in F stops for white skins. Here the subtle tones of black emphasize the many nuances of dark skin colors.

We are caught in the web of these layered metaphors that defy the state of our present world with brilliant defiance. “Hail the Dark Lioness”! (until November 8).

Don’t miss the videos behind the “Lioness” and read the articulate catalog!

This entry was posted on September 23, 2019 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Feminism, Uncategorized.

A visit to the home of Alfredo Arreguín and Susan Lytle June 2019

Appropriately, a tangle of ivy hid the doorbell, but I knew I was in the right place because of the small pale red ceramic pig on the porch. As soon I entered the simple brick home of Alfredo Arreguín and Susan Lytle in North Seattle, I was immersed in a wonderland that echoed the jungles in Arreguín’s paintings. I immediately sensed the many layers of his life with Susan Lytle. Their connection flows through every surface in the house, filled with carved wooden sculpture and ceramics, rabbits, elephants, dogs, turtles, and composite beasts (those wonderful carvings from Oaxaca) arranged in careful ensembles throughout the living room and dining room.

The unity among many cultures and the universality of the creative impulse is a theme of the house and of the art created there.

First, Susan introduced me to the delicate “Queen of the Night” flower, a type of cactus that blooms for only one night with an exotic blossom. They are one subject of her paintings. (I of course immediately thought of Mozart’s Queen of the Night and her extraordinary aria, like a one night exotic blossoming itself). Nearby on a table was a Jewel Orchid, a lush jungle plant with delicate flowers.

Figure 2 Anonymous painting of a kitchen

Arreguín pointed out a long brick stove in an anonymous painting in his dining room, remarking that he fed sticks of wood into a stove like that while living with his maternal grandparents who raised him in Michoacán Mexico. His grandfather first bought Alfredo paint supplies and encouraged his art. He also took Arreguín along as a small child on a trip to Las Canoas deep in the jungle. It made a deep impression.

After his grandparents died in 1948, Arreguín moved from one family member to another, initially living with his mother, then an aunt, then his father, a boarding house, and finally another aunt. While still a teenager, as an assistant to engineers, he had a more immersive exposure in the intricacies of life in the jungle, this time in Guerrero. He would never forget that experience.

But by extraordinary serendipity he was invited to live in Seattle by a family he met when they were lost as tourists in Chapultepec park. As a result, he came to the US in January 1956. Then he was drafted into the army, and sent to Korea. Fortuitously, while serving in Asia, he was able to visit Japan. The rhythms and patterns of Japanese art as in the waves of Hokusai, for example, permeate his art to this day.

On his return, Arreguín earned two degrees at the University of Washington.

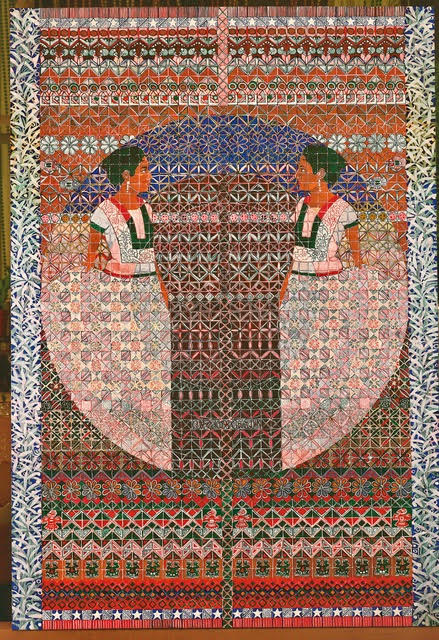

Figure 3 Alfredo Arreguín Tehuanas 1982, 64 x 43” Courtesy of the Artist

As we spoke in the dining room I was facing an early painting Tehuanas from 1982 in which two female dancers face one another, their white dresses forming two separated sides of a circle, the space between them charged with energy. The dancers, static and stately, seamlessly occupy a single flat space with a dense pattern of green, blue, red, orange, pink and lilac. These patterns and colors invoke the spirit of indigenous art in Mexico, a life long reference point for the artist.

Arreguín explained that this was an early example of his use of pattern when it took him hours to create the repeated geometric shapes.

Now, he says, it just flows from his fingers.

I was amazed when I went to the simple basement studio and saw that Arreguín and Lytle shared a single long room. There was a slight demarcation created by a pile of Alfredo’s paint tubes and Susan’s easel. Such a permeable barrier between two working artists suggests intense focus, as well secure interconnections. They met in 1974 at the Blue Moon Tavern, a longtime hangout for beat poets most famously, Jack Kerouac.

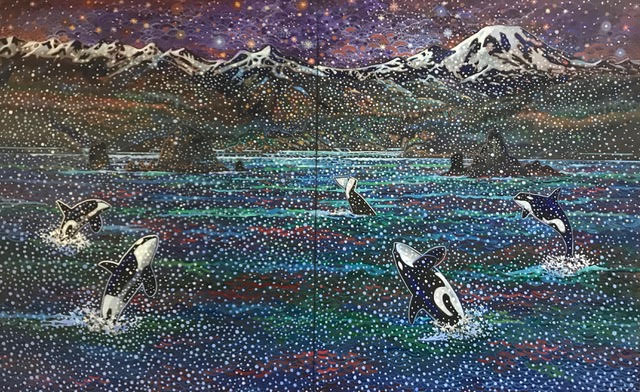

Figure 4 Alfredo Arreguín Twilight 2019 60 x 96”

On Alfredo’s easel was a large painting of leaping orcas called Twilight. As we looked at the painting he now and then added a white dot to the surface. Arreguín’s many paintings of wildlife in jungles and the sea speak to his great sense of the loss of our rich biodiversity. As he stated, “We are the most dangerous animals on the planet.” The mighty orca whale in our Southern Resident pod about which Lynda Mapes has written so eloquently in the last two years in the Seattle Times, numbers only about 73 today, and they are starving for lack of the chinook salmon they need to survive. The salmon, like the orca, are dying out, both threatened by environmental challenges from pollution to noise.

I felt deep sorrow permeating the painting, reinforced by its gentle lighting between day and night. The leaping orcas were celebrating the birth of a new baby, but I felt the threat hanging over the joy. Only last summer a baby orca born to our Southern Resident Pod died in less than an hour, and then was carried for 17 days by its mother in a tragic epic journey. This summer we have heard that the Pod has left our region in desperate search for food, and three more orcas have probably died.

In the other end of the studio several of Susan Lytle’s completed paintings of the “Queen of the Night” hung on the wall, and a work in progress on her easel. Seeing these paintings at the end of my tour, fit perfectly with my introduction to the one night bloom and death of the Queen of the Night flower as I entered. Lytle carefully explores the rapid transformations and intricacies of these briefly surviving blooms in sequences of small paintings.

Figure 5 Susan Lytle Queen of the Night 2016, 30 x 24”Courtesy of the Artist

Figure 6 Susan Lytle Night Bloom 2016, 18 x 14” Courtesy of the Artist

Figure 7Alfredo Arreguín Birds of Paradise 2012 42 x 50” Courtesy of the Artist

As I left, I looked at Birds of Paradise, hung directly opposite the front door. The multicolored birds fly and perch on branches against a background suggesting a sea and sky. The composition subtly suggests the Asian influence in his works. These birds fly joyfully in counterpoint to the leaping of the huge orcas who seem weighted with sadness. Arreguín said this painting has just been purchased by 4 Culture for the Children and Family Justice Center. He wanted to bring a feeling of freedom into a dark place. Here is his narrative:

“Birds have flown the skies since time immemorial. These beautiful creatures have inspired artists for centuries, not only with their graceful flight, but also with their song and plumage. As an artist, I am no exception. I have been fascinated with these flying miracles most of my life, and they appear in my paintings as memories of my childhood, of my travels and my daily walks and communion with Nature. This painting, Birds of Paradise, is an attempt to describe my amazement and delight upon discovering these flying jewels from Indonesia and Australia. As an artist, I would never try to compete with Nature’s creations. So, in Picasso’s words, I paint the lie that makes us see the truth.”

So on this visit, I experienced Arreguín, the man, who sorrows for the loss of the connected intersecting web of life on our planet, and Arreguín, the painter, who celebrates life in all its forms.

His partner of many years, Susan Lytle introduced me to the exotic habits and intricate beauty of the “Queen of the Night.”

Together they sing a song that goes straight into the heart.

This entry was posted on August 20, 2019 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Thank you Ludovic Morlot

Last night we heard Ludovic Morlot our brilliant music director of the Seattle Symphony conduct his final concert as director at Benaroya Hall, Richard Wagner, Claude Debussy and Leos Janacek. It was on the theme of love. It was a stunning concert that seem to be caressing us with one beautiful complex work after another. The music reached into every corner of the orchestra, we heard outstanding brass, woodwind, strings, drums and voices coming together in his final gift of his conducting to us and to Seattle. We could also sense the orchestra playing better than ever as a gift to Ludovic himself. He chose a choral piece as part of the concert in order to include the Seattle Symphony Chorale and the Northwest Boys Choir.

I was bathed in the music.

At the same time I was holding the memory of Pieter Vance Wykoff, in my mind. He died last week in his mid forties from brain cancer. He was a bass trombone player with the Hong Kong Symphony, a delightful young man whose life was cut short. Every time the bass trombones played last night I thought of him.

To give a sense of Morlot’s work in Seattle here is an article I wrote about just one week in March, 2019|

“In the last few weeks, our Grammy award-winning Seattle Symphony has outdone itself performing difficult contemporary music and presenting FOUR world premieres!

The Chamber Music concert featured Tessa Lark in a preconcert (they always have a free recital before the main concert.) Lark is a violinist, but she played fiddle inspired violin music. Her humorous dialog explained the intersections of the blue grass music of Appalachia with classical music. She also played pieces of her own and an impossibly difficult contemporary work by John Corigiano. Then in the main concert the highlight was Leoš Janáček String Quartet No. 1 “Kreutzer Sonata” led by Grammy award nominated violin player (and artistic director of the Seattle Chamber Music Festivals) James Ehnes. This intense piece of music featured crashing conflicts played by the two violins, cello and viola, inspired by a Tolstoy novella about infidelity sparked by a violinist falling in love with a pianist while performing Beethoven’s Kreutzer Violin Sonata. That was thrilling!

We were so fortunate to go to “Celebrate Asia,” friends gave us their fabulous center of the orchestra tickets. It included a stunning succession of Asia related and/or composed pieces including a world premiere by Chia-Ying Lin, a 28 year old Chinese composer who won a competition for young composers sponsored by the Seattle Symphony. The highly experimental work Ascolsia, featured instruments and musical tones inspired by folk music of Taiwan. Shiyeon Sung, a South Korean born conductor, dynamically led the orchestra. A brilliant piano player, Seong-Jin Cho, also originally from Korea, played Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. It was stupendous. Katherine Kim then sang a wildly contemporary song cycle by Unsuk Chin, also Korean, based on Alice in Wonderland. Then the undauntable Symphony gave us Pubbanimitta for Orchestra by Thailand’s most famous composer, Narong Prangcharoen. Wow!

But there is even more. Later that week we heard another amazing pianist, Jonathan Biss, who had commissioned contemporary composers to create works inspired by Beethoven concertos. First he played Beethoven’s third concerto and then a SECOND concerto, the World Premiere by Caroline Shaw, inspired by the Beethoven, but totally avant-garde of course.

And last, and maybe the most thrilling of all, was the Silkroad Ensemble with Kinan Azmeh, a Syrian clarinetist, originally from Damascus. It was a truly international concert, inspired by “Beyond Borders,” a Seattle Symphony concert two years ago reacting to that original dreadful travel ban (Azmeh performed then also, barely able to get back in the country). Sandeep Das, from South Asia, gave us staggering drumming, and the world-renowned Chinese composer Wu Man performed several solos on the Pipa, a stringed instrument like a lute. Expanding our geography further, we heard the dynamic Venezuelan Christina Pato on Galician bagpipes, playing a fast moving “Latina 6/8 Suite” that included brilliant musicians from the symphony performing solos on the bass, viola, cello, and violin.

Again, the Seattle Symphony had commissioned premieres, one by the award winning Chinese composer Chen Yi (she had been composer in residence at Seattle Symphony in 2002–03). Then Kinan Azmeh transported us as he played his own new work, a clarinet concerto with the Symphony. As he played, I felt the deep tragedy of Syria in his music, in his life.

We are incredibly fortunate to have this amazing Symphony and its commitment to contemporary music. They are even launching a new venue Octave Nine, at Second and Union, which will feature an acoustic system that uses 42 speakers and 30 microphones, modular surround screens and movable panels that will immerse the audience.”

I couldn’t help thinking as I listened to the concert last night that classical performers are still dominantly white, we have quite a few Asians in the strings, one African American cello player, and of of course the incredible Demarre McGill, the African American flute player. The Boys choir was a sea of white faces, except I think one Asian. Knowing the schedules of my own daughter and her family, each of those boys came from the privilege of having a parent who could support them extensively, both logisiticaly and financially. My grandchildren fortunately have a very good music program in their public school in Nutley New Jersey, but carrying and delivering for an intense commitment like a choir is not on their horizon.

In 2006 we heard from the Young Eight, an entirely African American ensemble of classical musicians put together by Quinton Morris, our world famous violinist who teaches at Seattle University, originally came from Renton and is committed to reaching out to low income neighborhoods with music education in his Keys of Change. I wondered why there was no sign of him at the Symphony since that performance.

But the strength of Ludovic Morlot’s tenure was reaching out to many communities in Seattle, collaborating with groups such as Path with Art, offering free concert attendance to youth and teens accompanied by their parents, artists in residence, new commissions, encouraging young composers. Who knows how much of this will continue.

Thank you Ludovic Morlot for your generous 8 years in Seattle.

This entry was posted on June 24, 2019 and is filed under Uncategorized.

“Cecilia Vicuña: About To Happen” at the Henry Art Gallery

The Henry Art Gallery’s exhibition of Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña gives new life to found materials. On two walls and a large floor area, Vicuña placed over 100 Precarios, very small sculptures created from detritus gathered on beaches since the 1960s. Precarios refers to the delicacy of the tiny sculptures, but they also speak metaphorically of fragile indigenous recovery from colonial erasure, and the planet’s current threatened condition.

As with the idea of Precarios, Vicuña’s art moves from micro to macro in scale and concept. The Balsa Snake Raft to Escape the Flood wends through the center of the gallery with a wild range of materials: bamboo, willows, twigs, fishing line, beads, rope, net, styrofoam, plastic, feathers. As we look at this long shape, the snake seems to explode into the air, its fragile materials unable to support us.

Vicuña weaves words as well as objects. High at the top of two facing walls Vicuña placed a poem in one single long line. Underneath is a case filled with her poetry books and “Book Objects,” tiny sculptures with brief handwritten texts that offer enticing tidbits of ideas. This tiny book is called “Des a par e cer (Disappear) 1980s. It says “To appear is to be in pairs/ To Disappear is to unpair.” Well you can think about that.

Caracol Azul (Blue Snail), a large bail of unspun blue wool, partially unrolled on the floor, creates a giant image of a snail trail. From an indigenous perspective unspun wool “stands for cosmic gas and interstellar dust that gave birth to galaxies and water.” And the snail trail connects to the beginning of writing.

At the far end of the gallery, the installation Burnt Quipu made of orange, brown and yellow lengths of wool that hang from the ceiling, creates a dense forest like environment that we are invited to walk through. It commemorates the forest fires of last summer.

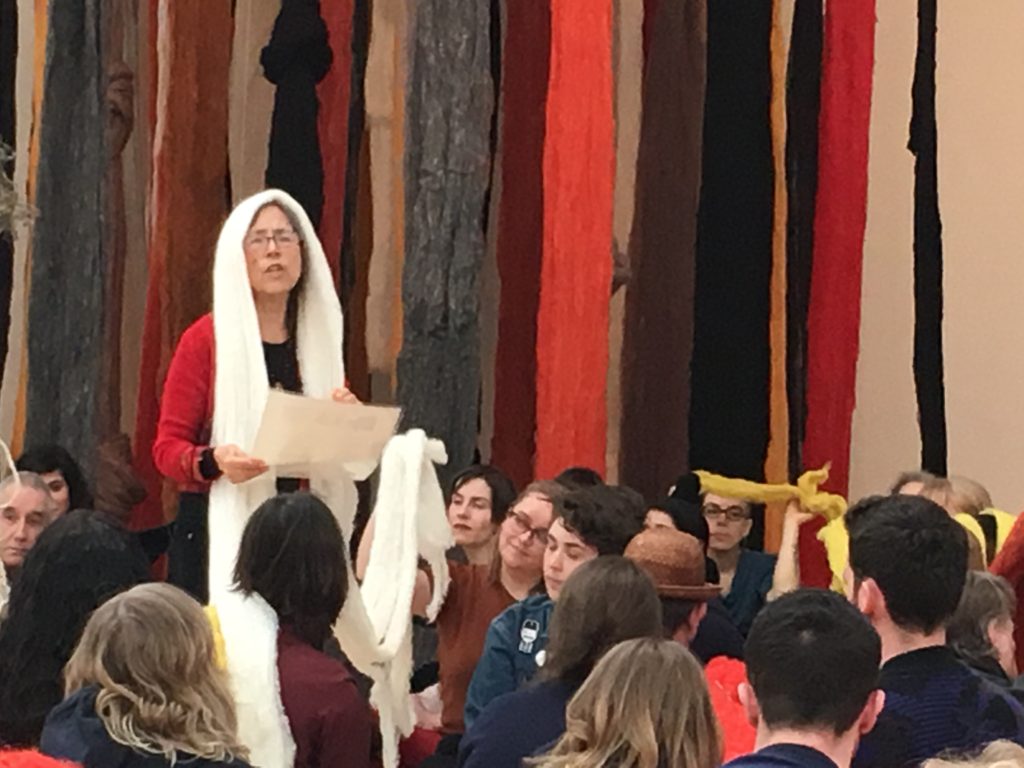

Vicuña incorporated several long Quipu in a performance at the museum: we passed them from one person to the next creating a connection and community among the almost 100 people there, as she sang a poem wearing a white Quipu.

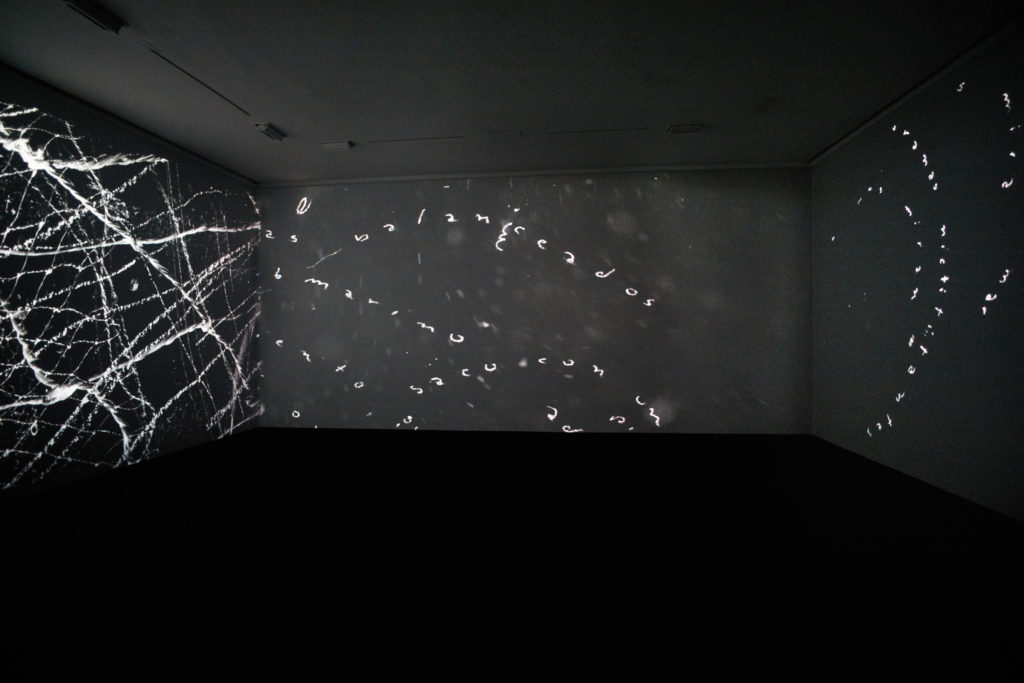

Vicuña references climate change in several media. Her long raft suggests the difficulty of surviving sea level rise. A three channel digital video La Noche de las Especies, (Night of the Species) animates her drawings of microorganisms and immerses us in both their wonder and their extinctions. Finally, there are six short films in the auditorium. In one of them , she collects seeds while she sings “Semiya,”a seed song (which you can also hear in a Precarios installed in a corner of the gallery) .

As I moved through the exhibition, I felt the poetry both visual and textual, permeating me. The changing scales from large to tiny, the resurrection of the most humble materials into extraordinarily fascinating sculptures, the singing, the films, weave an experience that is more than just viewing. Walking through the gallery is a walk through a forest, but this forest is constructed from words and found materials only some of which are natural ( as the forests and nature in general today is so often littered with plastic).

It speaks of the past and the present, but leaves a question mark hanging over the future.

This entry was posted on June 11, 2019 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and N Scott Momaday

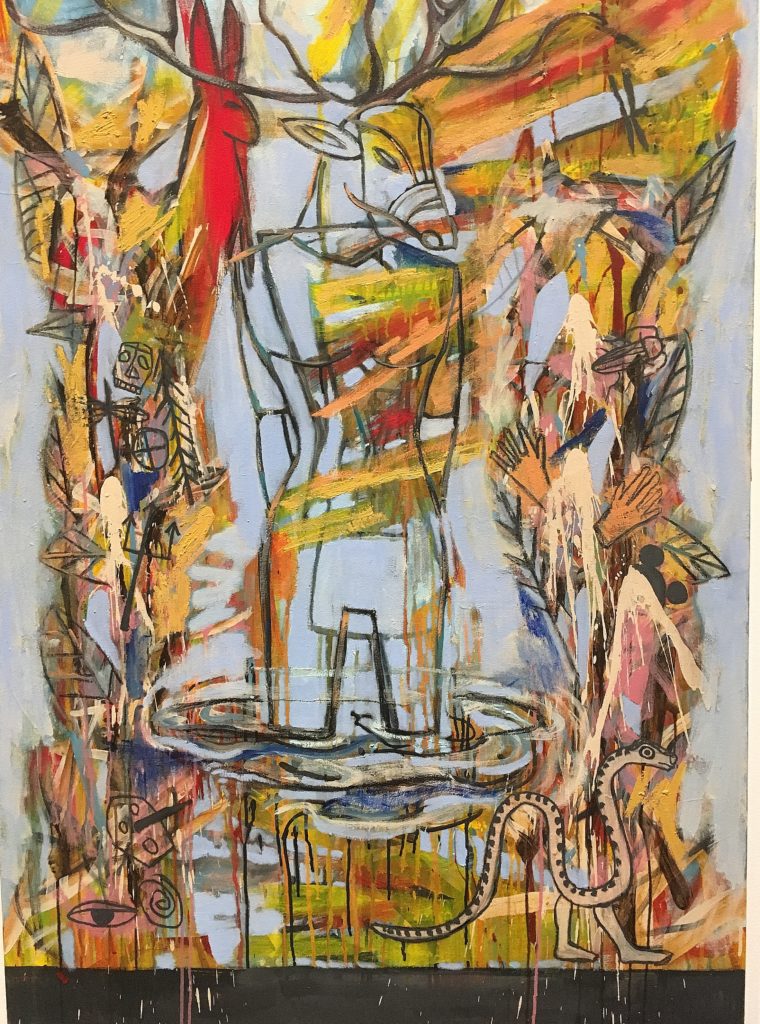

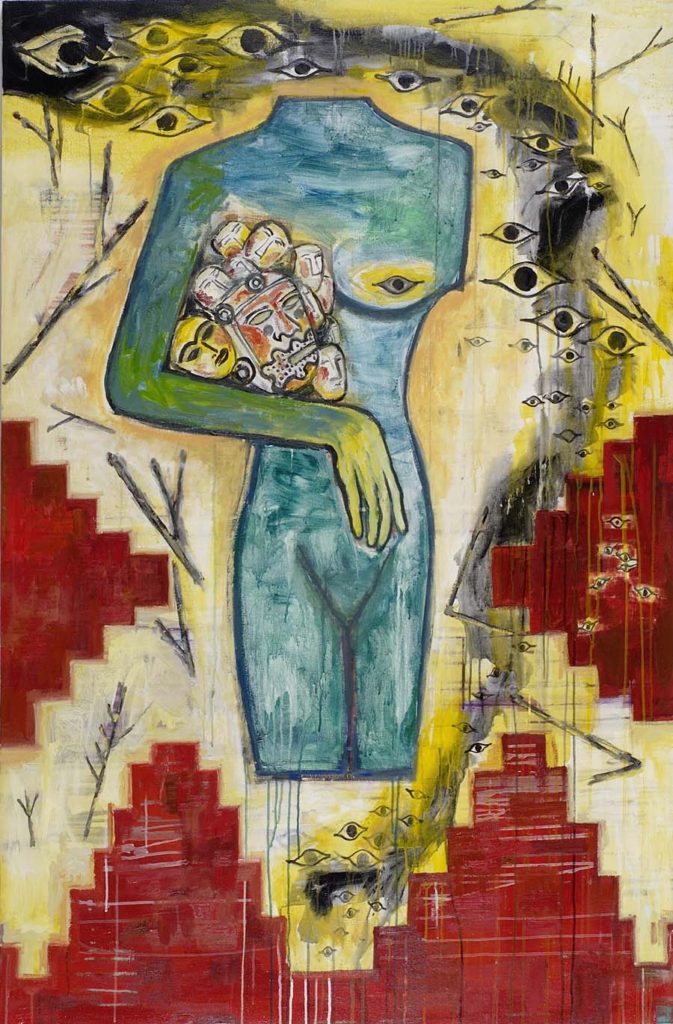

“Jaune Quick-to-See Smith In the Footsteps of my Ancestors) at the Tacoma Art Museum (until the end of June) confronts us immediately with her deep connection to the natural world and what we are doing to it as colonial extractors. The Swamp, 2015, puts the current crisis right in our face in both the styles of white modernism, and native abstractions.

The art work is described as follows: “A figure both human and animal stands in a swamp, wreathed by symbols of the vivid life one finds in swamps. Humans and animals are caught up in the stew of action, just as none escapes thoughtless decisions that poison the air and water that everyone needs. This painting acknowledges the importance of swamps within our ecosystems, their cleansing waters, and their rich habitat.”

In the central figure, Smith stated that she “created an elk anthropomorphic female figure, converted from a male elk love medicine.” As we look at it, we feel ever more deeply entangled and disoriented. The central figure is standing knee deep in a pond (a stew). The most distinct creature is a walking snake, in the lower right that seems to be walking away from the devastation. Embedded in the hot yellows and reds are fragments of masks, feathers, a pair of hands, an “Indian” stereotype profile yellow face with a single feather headdress. Oops there are the ears of Mickey Mouse ( an obvious reference to Disney, here standing in for corporate takeovers)!, In the upper left a majestic trickster rabbit ( named Nanabozho) oversees the entire disaster.

According to Gail Tremblay’s catalog essay ” “Nanabozho was sent to earth by Giche Manitou who assigned him to name all the plants and animals and to creat a system of mnemonic mark-making that would help humans remember the order of things in ceremonies and stories”

We feel the spilling of blood, the disruption of the sun, the pallid blue background indicating a vast space on which we have laid spoil to the planet. We can also see the devastation wreaked on native tribes on this continent in the last 350 years embodied in the paint strokes and the cascading images. Linear outlines suggest pictographs, but not literally, more invented, there is a Mexican mask, a bomb.

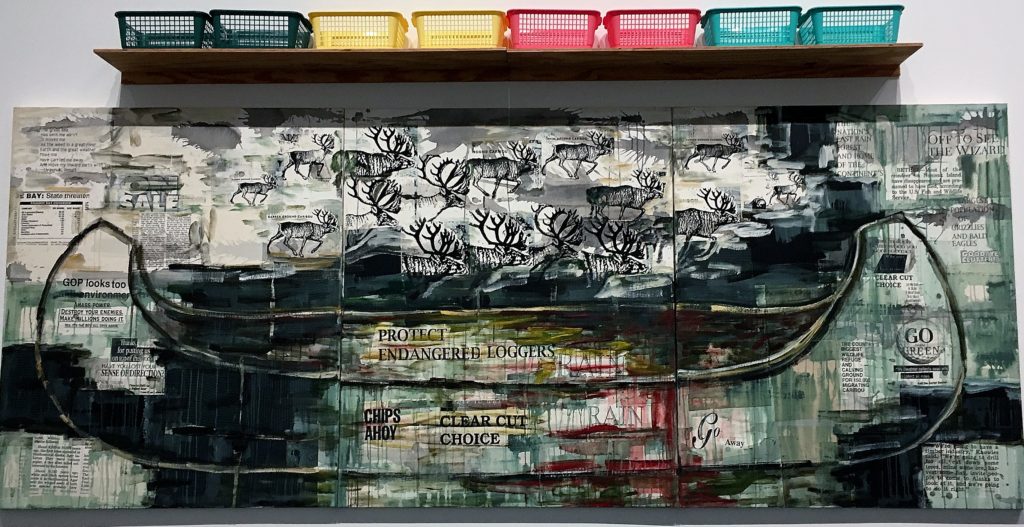

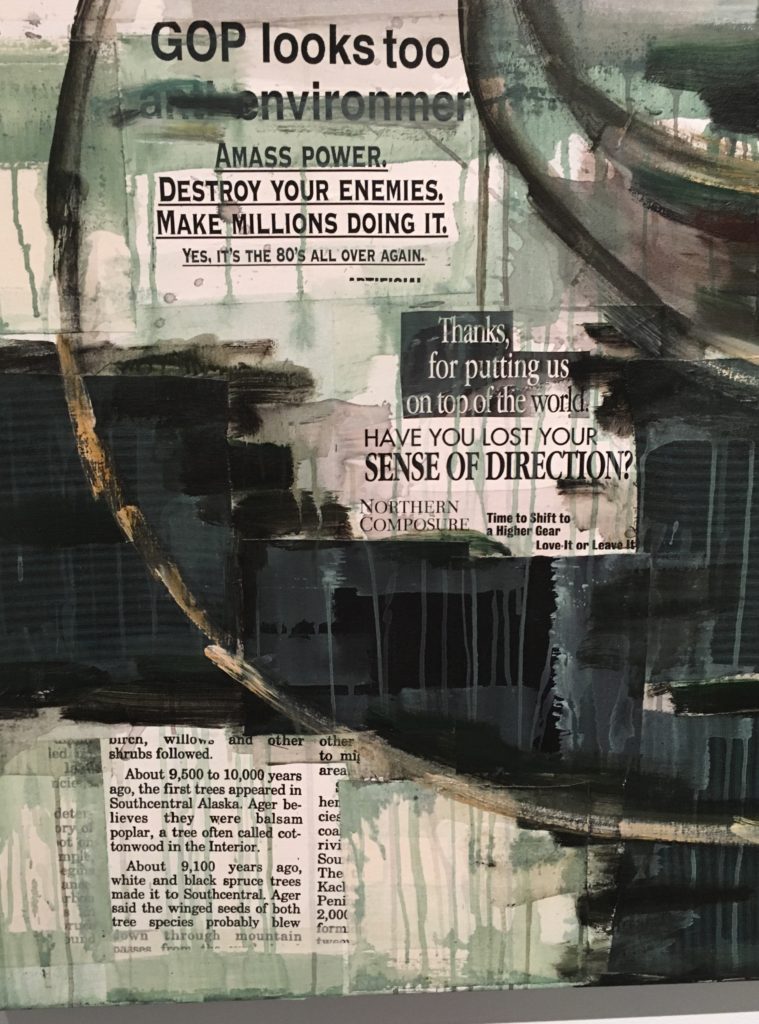

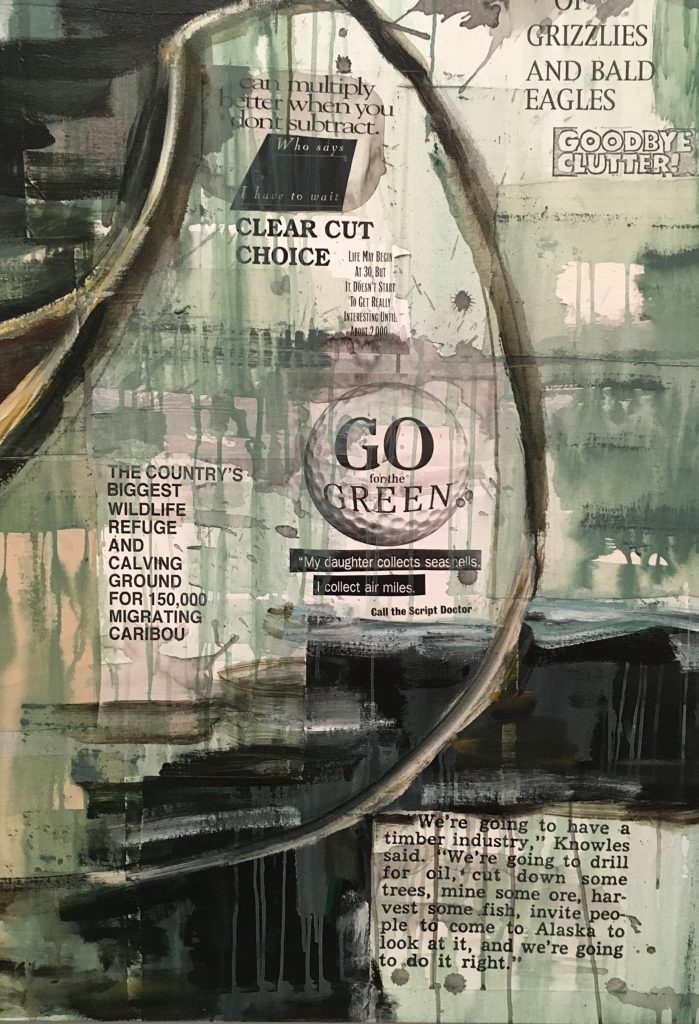

And that is only one painting! I give you Tongass Trade Canoe. This astounding ecological statement from 1996 is chillingly pertinent to our present catastrophe. It refers to the Tongass National Forest in Alaska, the calving ground of many caribou where oil is being drilled.The plastic laundry baskets suggest the trivial products that come from the destruction of the natural environment.

According to the Southeast Alaska Conservation Council “The Tongass contains nearly one-third of the old-growth temperate rain forest remaining in the world, as well as the largest tracts of old-growth forest left in the United States. Old-growth temperate rain forests hold more biomass (living stuff) per acre than any other type of ecosystem on the planet, including tropical jungles. The Tongass alone holds 8 percent of all carbon stored in U.S. national forests and is recognized as a globally significant carbon storage reserve.

” In fact, the Tongass is the last National Forest to allow large-scale clear cut logging of ancient old-growth trees, and according to draft plan released this year, will continue to permit this outdated practice for another 15 years. “

Here is a detail. Surrounding the huge canoe image are references to the devastation being wrought on the environment as a result of greed, exactly our problem today. This huge painting was completed more than 20 years ago. Its genius is the deadly ( literally) serious issue, the calving grounds of caribou, that you see marching across the top of the painting.

But it also has humor, ” Protect Endangered Loggers,” “Chips Ahoy” “Grizzlies and Bald Eagles, Goodbye Clutter” “Clear Cut Choice”

I wrote about Jaune Quick-to-See Smith in my book Art and Politics Now in the ecological chapter which addresses the huge difference of “enlightenment” attitudes to nature – that it is separate ( and inferior) from humans- and the indigenous perspective that we are part of nature. But in my book I illustrated “Fear,” also in the Tacoma exhibition, a powerful anti war work, her excruciating images of war overwhelm us with their detail and specificity.

Here is a series of four prints that bring together humor and tragedy. The US tried very hard to obliterate the native point of view, the native peoples, the native cultures of this country. Thank goodness we white people failed in that endeavor, we may have only their perspective to save us now, from our own ways.

In the movie recently screened at the Seattle Public Library, “Words from a Bear” about N. Scott Momaday, we were once again confronted with both the ongoing strength of the Native American message of our embeddedness in the land, in nature. Beside that we learned of the US efforts at genocide: slaughter of buffalo and horses,the banning of religion, especially the Sun Dance, forced marches to reservations far from familiar lands, boarding schools- the effort to make native children white by removing them at the age of four from their families; allotments which broke up tribal territories, then after World War II there was the urbanization which isolated natives again from their culture and families, on and on.

But Momaday was lucky. He did not go to a boarding school, his parents were story tellers and writers and painters and teachers, he got a full scholarship to Stanford and received a Ph.D. in 1963.In 1969 he won the Pulitzer Prize for his book House Made of Dawn. This astonished him and thrilled the entire indigenous community, as one writer declared we moved

“beyond the ethnographic past.”

The main theme of the movie though is that he “invested himself in his landscape.” He stated “I am who I am because of the land.” His voice is crucial in today’s world as we are increasingly alienated from nature. He says we cannot separate from the land. It is that insight that we all need as our culture increasingly is devolved into looking at life through a small screen filled with scarce metals taken from the earth.

This entry was posted on May 30, 2019 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Edgar Arceneaux at WaNaWari

Our library models are on the stairs

Photograph by Inye Wokoma

WaNaWari is a new cultural center in the Central District. Located at 911 24th avenue on the site of Inye Wokoma’s grandmother’s house, it is “Reclaiming Space for Black Art and Stories.” Four people are collaborating: Inye Wokoma and Elisheba Johnson are African American artists affected by gentrification and displacement . Jill Freidberg and Rachel Kessler, are white artists using art and stories to challenge white supremacy, especially as it is expressed through gentrification and displacement.

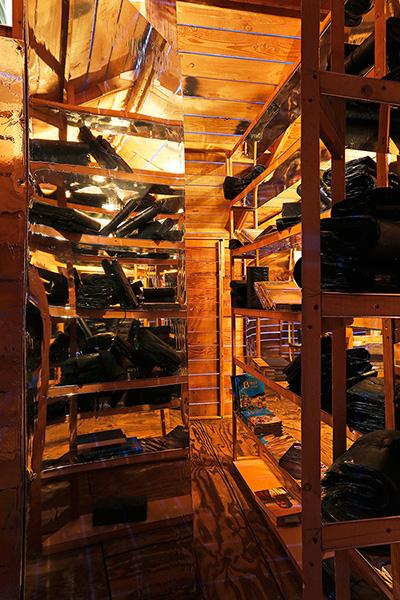

A week ago we gathered for a special event with Edgar Arceneaux, visiting artist from Los Angeles with a current exhibition at the Henry Art Gallery “Black Book of Lies” (until June 2 ). The exhibition is a space that looks from the outside like a wooden structure of hard to characterize design somewhere between slave cabin and space ship.

Inside is a labyrinth filled with books in various conditions.

As we wind through it, it is a tight space, a bit claustrophobic. You can barely pass between the shelves filled with many types of books: first of all are burnt scroll-like objects, a reference to the burning of the Library of Alexandria. Then you run into your own reflection on a shiny surface. Whoops! are we intruders or destroyers or tourists or book lovers filled with horror? As we wind into the space (a labyrinth with a false ending, a center, and a way out) the books on the shelves change, first there are altered books on contemporary art, particularly the book Arte Povera, about contemporary Italian conceptual art, which lends itself easily to other sardonic titles ( I leave it to your imagination), Seven Pillars of Wisdom by T.E. Lawrence ( of Arabia) Darwin’s Origin of the Species, Lenin, Chaucer, Descartes, Bible stories, volumes of the Encylopedia Brittanica,. As we go deeper and deeper into the labyrinth we finally arrive at nine Bill Cosby books that have been stuck together unreadable, an indication of the huge issue with Bill Cosby today, cultural icon to disgraced predator. We are happy to find the exit.

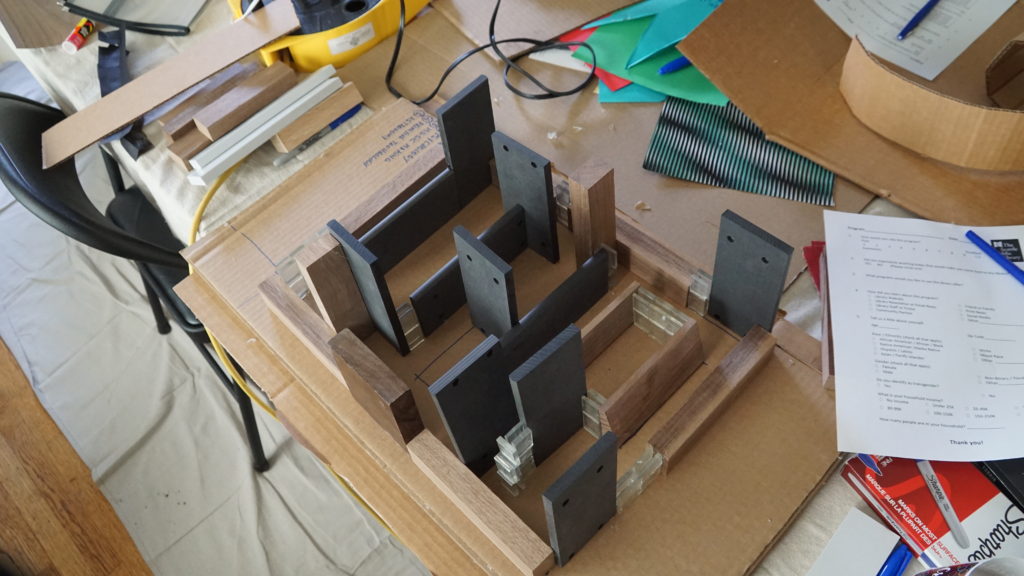

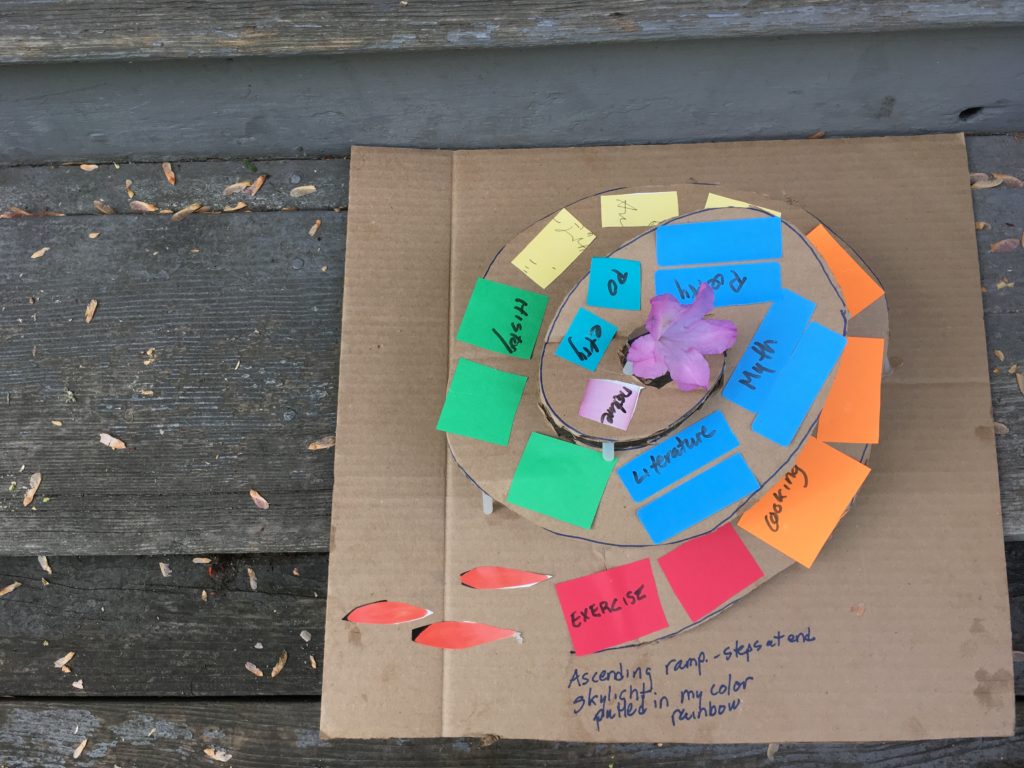

At the workshop we were asked to make our own small models for libraries. Arceneaux spoke of how books can destroy or transform, how they can get thrown out, how they create layers in our lives. With a piece of brown cardboard, some colored paper, magazines to cut up, a few bits of plastic and other things, we were asked to imagine a library building.

The results were astonishing, all sorts of imaginative structures and each of us told a narrative as we briefly presented them.

I was pretty intimidated as I am a writer, not an artist, but Edgar was super helpful and encouraging. My library, which everyone immediately compared to the Guggenheim of course, rises up through rainbow colors to a culmination in nature with a flower at the top. We were asked to include a reference to a book we were given and to have at least 5 different categories, mine were fairly obvious, exercise, cooking, art, history, literature, myth, poetry and nature. Other people had wonderfully imaginative categories such as giants for example.

My culmination of the spiral in nature is both an homage to my father who was a naturalist, and my love of nature. That sounds like such a cliche, but it is more and more true for me as I am increasingly concerned about alienation from nature as we plug something in our ears and look at our phones all the time. I feel privileged to remember to listen to the free concert of birds (thanks to my birding friends) and enjoy eating fruit and vegetables from a bounteous garden behind our house that my husband has developed ( I am from New York City so knew nothing about soil, fertilizer, etc).

Edgar gave me the flower on the top. Thank you Edgar. Thank you WaNaWari.

This entry was posted on May 26, 2019 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Yəhaw̓!

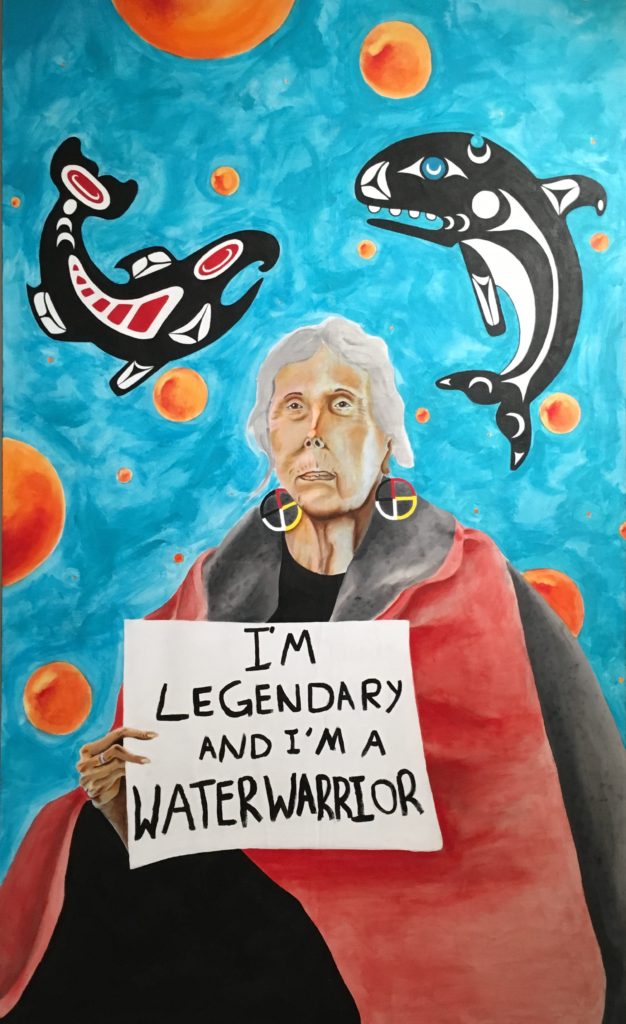

Contemporary Indigenous Art in Seattle’s King Street Station Inaugural Exhibition

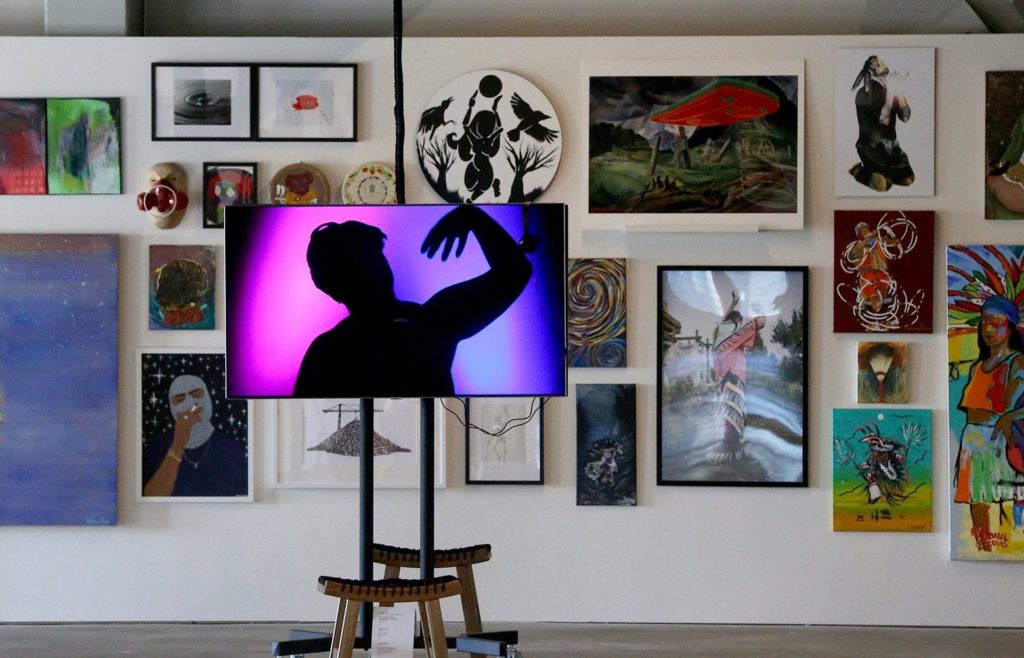

Prepare to be delighted and overwhelmed! As you enter the huge exhibition of contemporary Indigenous art on view at the new art space ARTS at King Street Station, the first work you see is an accumulation of objects hanging over the front desk by Catherine Cross Uehara (Uchinanchu/Hapa/Okinaway American) “between you & me & the Ancestors…” It includes photographs of her ancestors, a wedding dress kimono, memorabilia and much more.

Turn around and on the opposite wall is an archival film of the famous Vi Hilbert, (Upper Skagit) who singlehandedly saved the Lushootseed language from extinction, encouraging a community audience to “lift the sky” together. In her telling: “The Creator has left the sky too low. We are going to have to do something about it, and how can we do that when we do not have a common language? …We can all learn one word, that is all we need. That word is yəhaw̓—that means to proceed, to go forward, to do it.”

So, go forward and plunge into the exhibition of 200 artists from 100 tribes. The curators, Asia Tail (Cherokee), Tracy Rector (Choctaw/Seminole) and Sapreet Kahlon, accepted all indigenous submissions. They include children and elders, professional artists and beginners, all media from traditional cedar, bead work and dolls to digital and audio. We see sculpture, painting, photography, printmaking, text, cartoons, games, performance, skateboard, maps. There are all styles from realism to surrealism, to abstraction, to traditional, but mainly there are many mixes as well as approaches that need new names, rather than these tired Euro-American terms.

To enjoy the exhibition simply embrace its mind-expanding diversity, then immerse yourself in one wall at a time, each a compact exhibition. But the exhibition works as a whole as well. Large paintings and sculpture of all sizes animate the large space. Gaps between the walls allow a view through to another part of the exhibition.

Timothy White Eagle (White Mountain Apache), performance: “Songs for the Standing Still People”

Timothy White Eagle (White Mountain Apache) performed “Songs for the Standing Still People” within a space hung with jingles and chains that we are all encouraged to shake to create our own music. He called us to action against the “vast forces” that “will ravage us if we do not act” though a story of rocks that came together and changed the world.

Traditional indigenous media mix with contemporary media throughout the entire exhibition. Cedar hats demonstrate stunning dexterity and expertise by Kimberly Miller (Skokomish), Nancy Burgess (Grand Ronde/Umqua/Dakota), Roquin-Jan Quichocho Siangco (CHamoru) and Celeste Whitewolf (Cayuse/Nez Perce/Nisqually/Pitt River’Karuk’Hawai’ian/Confederate Tribes of Umatilla).

Hanging in the stairwell is a mixed media homage to weaving by Sara Siestreem (Hanis Coos/Confederated Tribes of Coos/Lower Umpqua/Siuslaw) “Eagle Machine dancing the beautiful.” It combines a cotton wood bark skirt with her photographs and mixed media references to indigenous history.

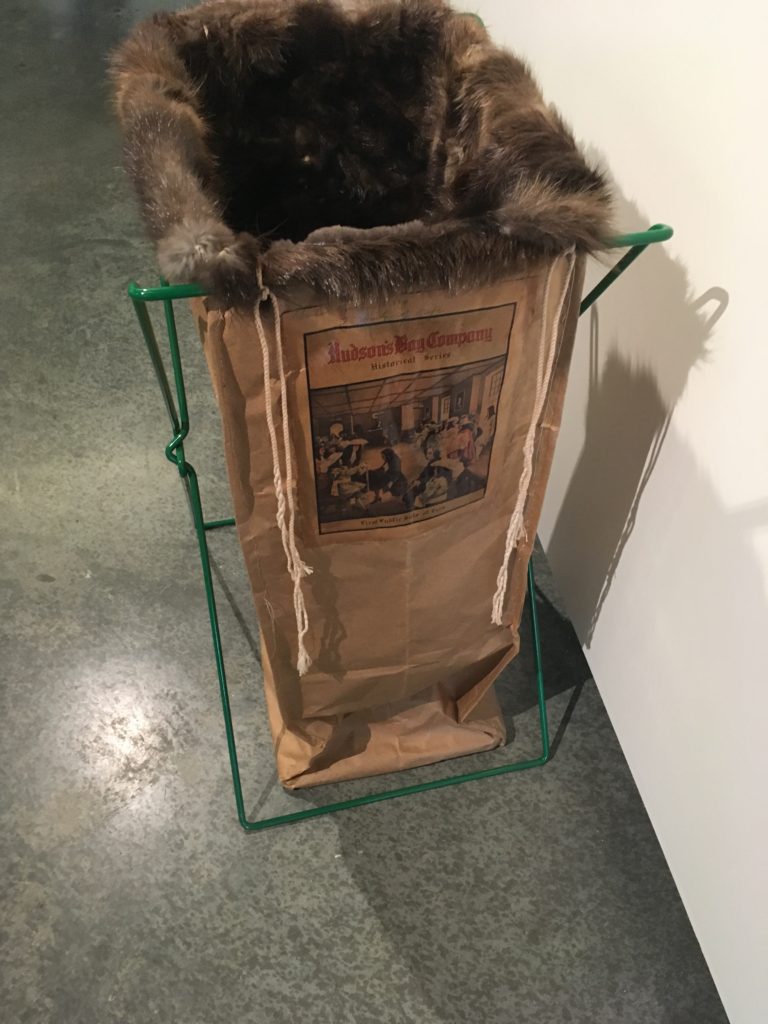

Other favorites include: Maureen Gruber’s (Inuvíaluít) “Colonial Shopping Cart” made from a large Hudson’s Bay bag and lined with fur;

Adam Sings in the Timber’s (Apsáalooke) photographs of young women in regalia re-asserting indigenous presence in various locations in Seattle;

Susan Ringstad-Emery’s (Iñupiat) Nalukatuq, 9 foot banner with a little girl tossing a star back into the sky (based on a folk tale), and celebrating children as the future of change;

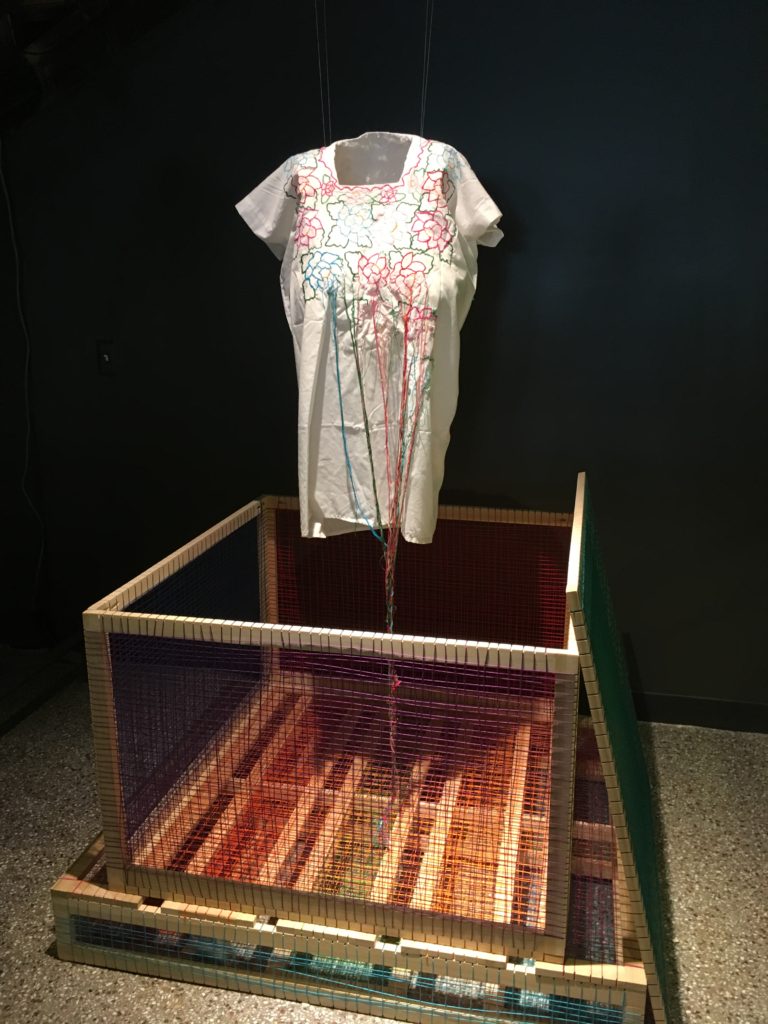

Priscilla Dobler’s (Mayan) “El renacimiento de la Sociedad: The rebirth of society” in the stairwell, commentary on traditional Mayan embroidery as its threads unravel into a contemporary geometric enclosure;

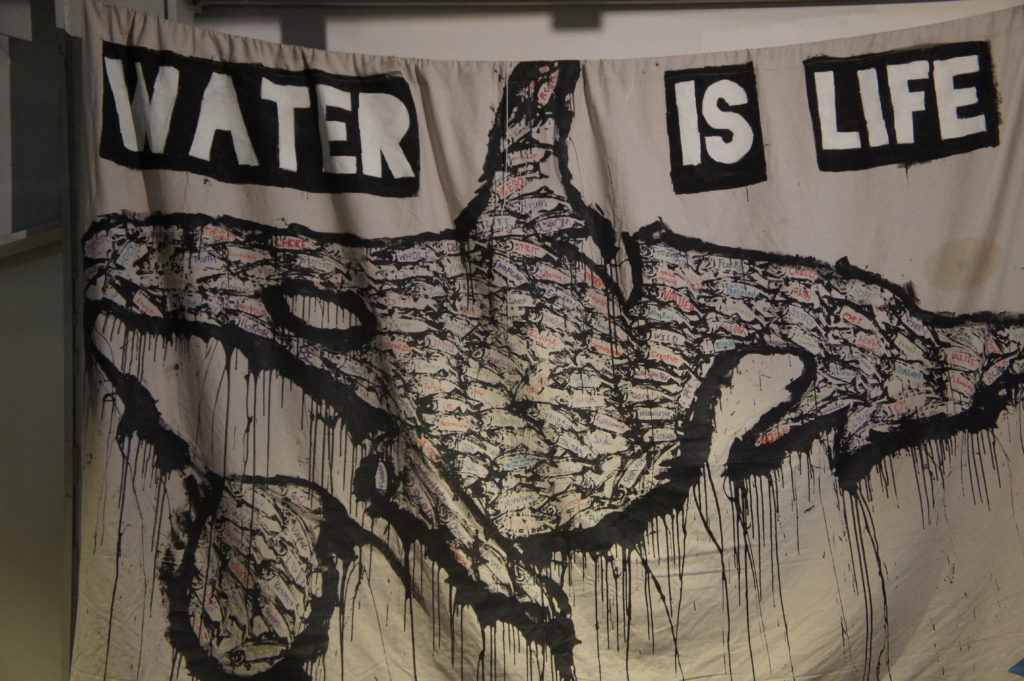

Jacob Johns’s (Hopi) “Water is Life” banner that speaks of freeing the Snake River, a reference to our threatened salmon and orcas because of the many dams on the Snake.

One of the most striking works is by HollyAnna “Cougar Tracks” de Coteau Littlebull (Yamama/Nez Perce/Cayuse/Cree) who upcycled 15,190 pieces of plastic to create a twelve by three foot “Big Foot” who “Lifts the Sky.”

The representation of elders in paintings and sculpture like “Ode to Ramona Bennett” by Taylor Dean (Puyallup) and the carved wood portrait mask of Vi Hilbert by Taylor Wily Krise (Squaxin), spiritually imbue the entire exhibition with their powerful spirits.

In addition to this huge exhibition there is a series of three Latinx/indigenous exhibitions at the Vermillion Café. The year-long exhibit also encourages new native curators at many venues, workshops for young native artists, films, and much more.

ARTS at King Street Station covers 7500 square feet, sponsored by the Seattle Office of Arts and Culture (ARTS) whose offices are in the same space. ARTS is dedicated to supporting and exhibiting people of color. Located at 303 S Jackson Street, it is open Tuesday to Saturday 10am–6pm and First Thursdays 10am–8pm.

This entry was posted on May 7, 2019 and is filed under Uncategorized.

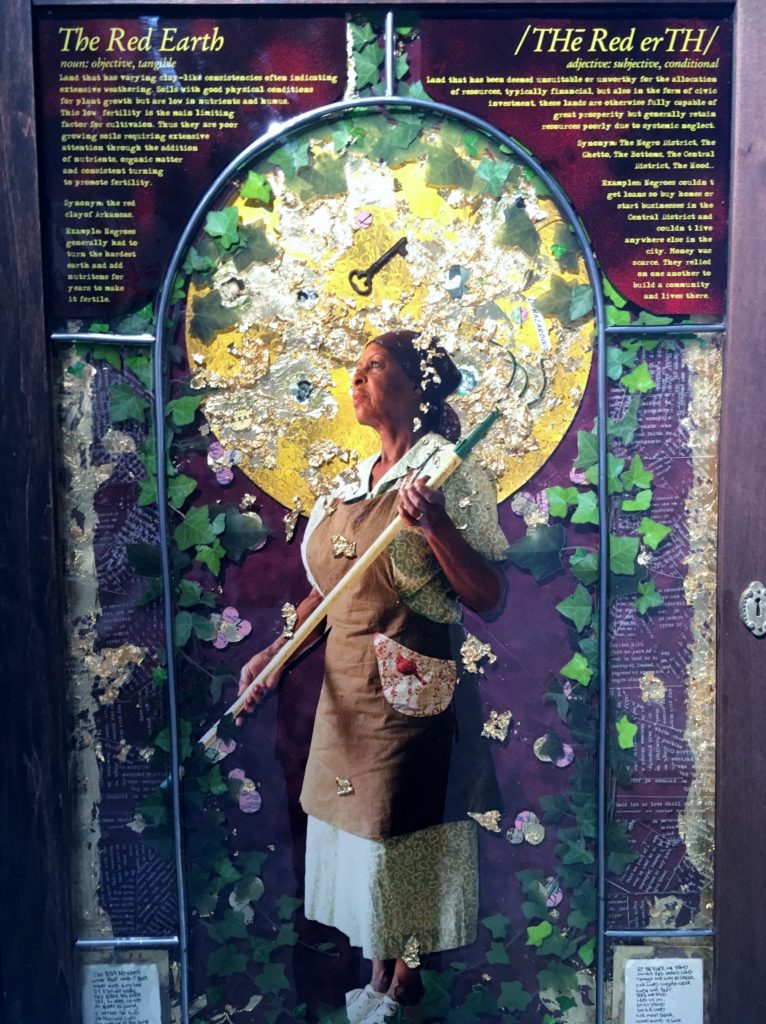

Inye Wokoma’s Amazing “Turning the Earth” at Liberty Bank Building

Inye Wokoma’s four mixed media art works inside the Liberty Bank Building lobby will be visible only to those who live there. So I am taking this opportunity to introduce these four intricate art works. Inye gave me an overview of their significance. The wall on which they are installed has two sides.

On the side you see is The Infinite Earth on the left and The Black Earth on the right.

On the other side of the wall is The Red Earth and The Green Earth. I have primarily quoted Inye’s articulate explanations here.

“It is a story of transformation and transcendence in four chapters based on the central metaphor of making barren land that fertile. Through this metaphor I am exploring the systemic racism African American faced upon migrating to Seattle in the 20th century, how we as a people confronted those challenges to build a community and the role Liberty Bank played in that story. “

“The visual motif references both Christian and Ifa spiritual traditions as a way to acknowledging the depth and complexity of our collective story as a people of the African Diaspora. I am both drawing from and expanding on these traditions by anchoring the imagery with deific figures that are rooted in the Central District daily life and mythical at the same time. “

Each piece has a story and together they comprise the larger story of the African American experience both coming from the South and living in the Central District.

The first part of the story is The Red Earth which he explained as the red clay earth of Alabama, for example. It is difficult to work , and low in nutrients making it low in fertility. He parallels this with the area of the city that was lacking in civic investment, and systematic neglect, as in the “Negro District, the Ghetto, the Bottoms, the Central District, the Hood” which created the difficulties of building community.

We see a woman who is both a maid and a farmworker holding a fork. Around her head is a huge halo, in the center of which we see a key, the key to a home, a home that is only a dream because loans for homes were not available in the Central District until the Liberty Bank was founded in 1968. She is both an Orisha of the Sankofa religion and a deity in Christianity, this strong black woman.

“The Red Earth – Rooted in our collective history of confronting housing discrimination and redlining, this panel connects this history with the agrarian lives many of our left behind in the south by paralleling working poor soil with building community under economic deprivation. The Red Earth is a visual metaphor for what it meant to build community with intentionality under the harshest circumstances. It establishes the conditions that made institutions like Liberty Bank necessary”

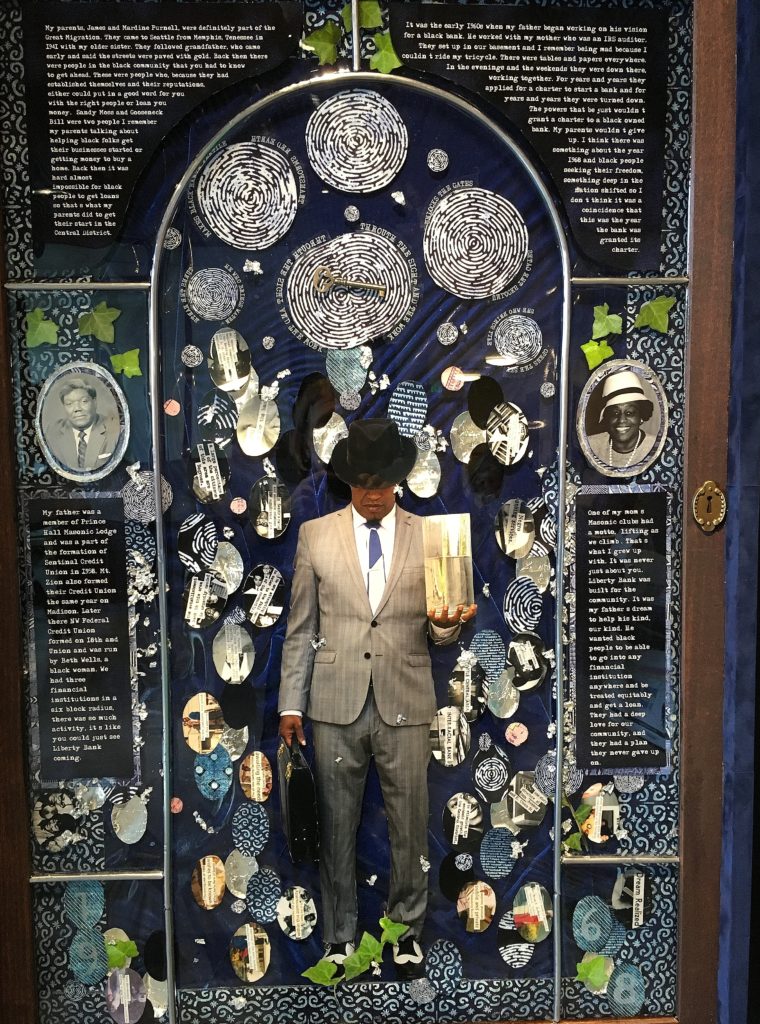

Next is the “The Black Earth,” the story of the founding of the Liberty Bank, black earth is rich in nutrients, that can nourish a community. The nourishment came from the founding of the Liberty Bank, and the story is told by the daughter of the founders, James and Mardine Purnell, whose photographs you see. Credit Unions preceded the bank in the 1950s and in 1968 the Purnells and seven strong community members came together to create the bank. We see James Purnell carrying a jug of water against a blue background that also suggests flowing water. The details of the process and deeds of sale are in the rain drops.

“The Black Earth – A more direct retelling of the founding of Liberty Bank, this panel uses the metaphor of black soil as a symbol of fertility. It evokes the bringing of water as a catalyzing force activating soil that has been prepared for cultivation and connects this to the Purnells’ mission to establish a bank that would bring much needed resource to the community African Americans were actively building in the central district. “

Next is The Green Earth which does not have a central figure. It embodies a coherent community, more abstract and more chaotic, with its roses and a gold wreath at the bottom, and a collage of photographs of events and people of the community.

“The Green Earth – A visual allegory for earth that is fertile and bountiful. It evokes the African American community in the Central District at its height and centers Liberty Bank’s role in that story. This panel is all about the complexity of a living social ecosystem. ”

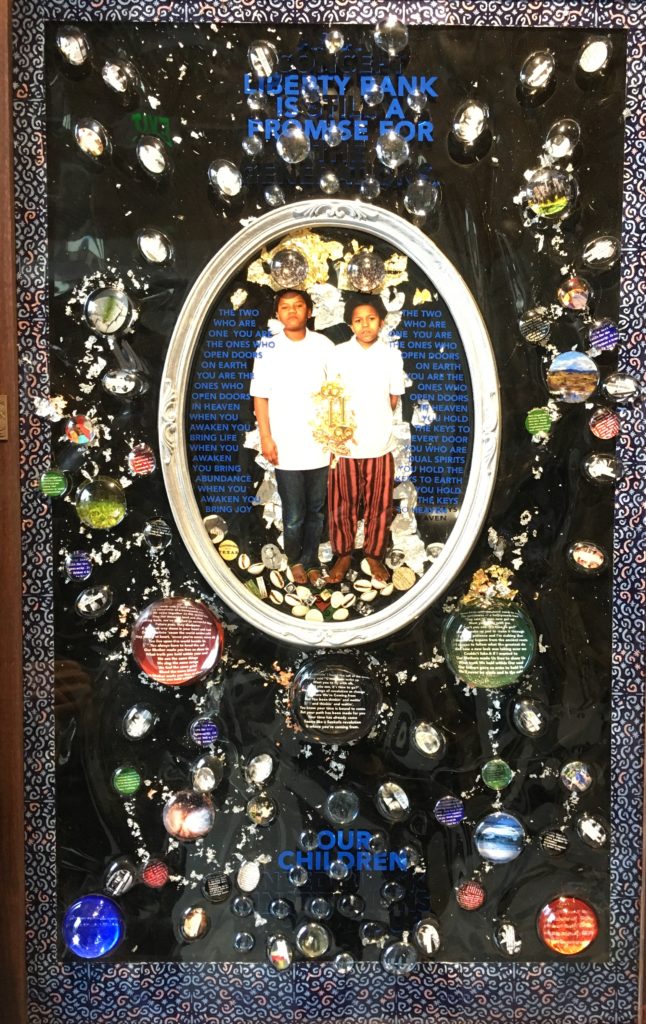

Last is The Infinite Earth . We see twins who will carry on the legacy of the bank, there are references to music, Sankofa, abundance, fertility, birth. Looking hard we can see photographs of Civil Rights Leaders like Malcolm X, and even photographs from the Hubble telescope inserted into some of the bubbles. It includes all the elements and the solar system. The cowrie shells refer to both currancy and abundance.

“The Infinite Earth – The panel explores the possibilities of the future by anchoring that potential in learning from the best that our collective past has to tell use. It evokes themes of transformation, endurance, connectedness, communal love, service, and vision as the heart of the of Liberty Bank story. “

This entry was posted on and is filed under Uncategorized.

Art and Regeneration at the Liberty Bank Building in the Central District

As we approach the new Liberty Bank Building on Union we can see from a block away that it is special. Its bold white with orange and brown accents stands high above surrounding buildings, a dramatic contrast to the innocuous developments on two corners of 23rd and Union, what was once the heart of the black community in the Central District.

Coming closer we see a striking African inspired pattern on the roofline overhanding the sidewalk. On the wall of the building is a “brisket” weave pattern interrupting the regular rows of bricks. The older bricks of the pattern come from the original Liberty Bank, the first African American owned bank in the Pacific Northwest, opened in 1968.

As a result of red lining, this neighborhood in the center of Seattle, became a concentrated black neighborhood. In 1968 national civil rights legislation made discrimination in housing, sales and rentals illegal and the Seattle City Council unanimously adopted the same laws. In that same year Liberty Bank made it possible for African Americans to buy homes in the Central District, or anywhere else if they wanted.

When I moved to 20th and Union in 1997 ( an early but not the earliest white here, some of my neighbors came a good ten years earlier), middle class professional blacks who survived the crack epidemics of the 1980s and early 1990s were still here. But they were mostly elderly. In the next twenty years, the neighborhood has become dominated by white “settlers” not unlike the innundation of whites who almost destroyed the indigenous population in Seattle in the 1850s. At the same time, the cost of housing has escalated, affected by the massive tech boom here, and the character of the housing, increasingly closed off condominiums with private garages, has destroyed neighborliness. Many small buildings with neighborhood businesses have been sold to developers who build larger, more expensive spaces. We treasure those landlords who are resisting this trend (I am so fortunate on my block on Union between 20th and 21st to have three such landlords).

Enter the six story Liberty Bank Building! It is on the site of the original Liberty Bank. Not only are the people involved committed to enabling African Americans to return to their historic roots with affordable and low income housing, they also built the Liberty Bank Building with 30 percent Women and Minority Owned Business Enterprises (WMBE). 87 per cent of the apartments have Black renters. All the commercial spaces are going to Black owned businesses, most notably Earl’s Cuts and Styles who has been across the street for decades.

This success would not have been possible without massive efforts on the part of many different groups, notably Africatown, Capitol Hill Housing, Byrd Barr Place and the Black Community Impact Alliance. Africatown has been particularly visible, and vocal under the dynamic leadership of Wyking Garrett, son of the irrepressible Omari Garrett and grandson of one of the original founders of the Liberty Bank.

He is seen here speaking at the ribbon cutting. See my husband’s article about that in the Leschi News.

My main focus here is to examine the stunning art installations some easily visible to the passerby, others inside the lobby and partially visible from the street.

I can’t think of a building since the government supported art projects of the 1930s with such an extensive art program focused on narrative. All the pieces address either the history of the Liberty Bank or the Central District.

To begin with the outside. Esther Ervin inset an original safe deposit box into the center of her “drum benches” along Union. She has smoothed them off to make a comfortable place to site and patterned the wood in a basket weave. She highlighted the top of the base with a tile design in Afrocentric colors.

Look up at the building and you see the etched glass panels by Ervin that outline the red lined Central District. In the right weather they reflect onto the building where you see plaques with poems by one of my favorite poets, Minnie Collins. Here are two of them.

Walk around to the entrance of the building framed by a square open gate with more safe deposit boxes inserted into the two sides (including their original hinges).

Dominating the façade is Al Doggett’s stunning mural celebrating creativity in the Central District, music, dancing and political resistance. It sweeps above our heads, filling the entire six floors of the orange façade. Doggett explained the design challenge of keeping the flow of the design in spite of all the windows.

Just beyond the entrance and visible from the street ( through a window) is Aramis Hamer’s mural ”Liberty” with multicolored hands reaching for a gold chain spelling out Liberty, referring at the same time to freedom from the chains of slavery, the chains of prison and the gold chains of hip hop performers. In the sky bills fly with the faces of the founders of the Liberty Bank.

In the courtyard Esther Ervin’s three bronze salmon with swirling designs “Struggle Against the Current” swim over reeds in a channel that will fill with water when it rains. They point directly to the difficulties that African Americans face in life.

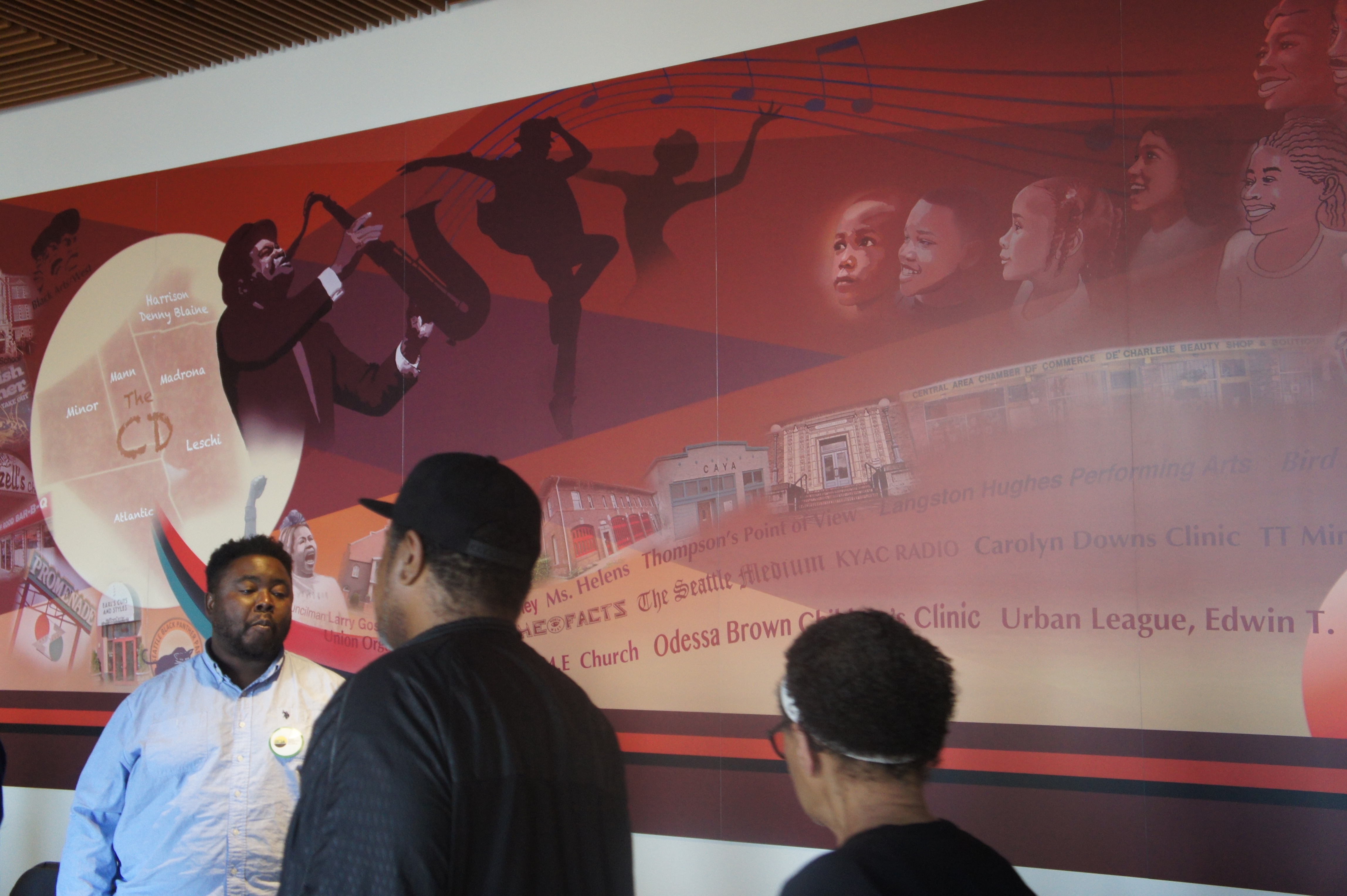

Inside the building the art visible only to those who live there or those who visit features Al Doggett’s large mural that details the history of the Central District. It names and depicts businesses, places, and people, some of whom are still with us. He unifies the complex composition with an undulating musical line emanating from a saxophone player and dancers and culminating with a choir of children and adults.

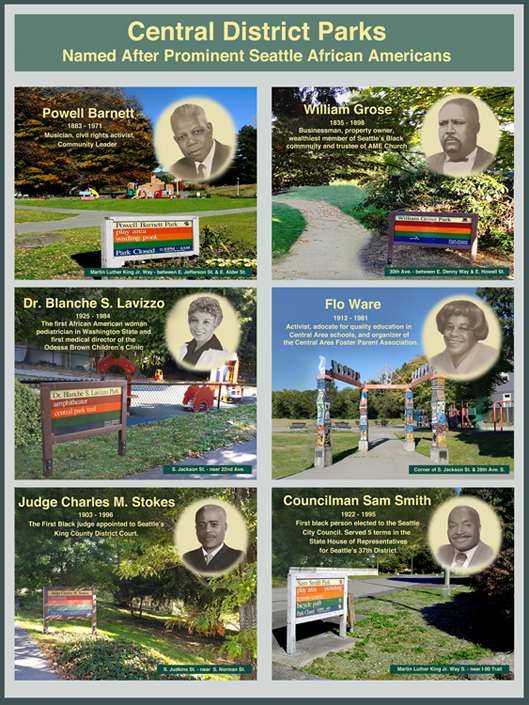

Doggett was also responsible for the panels outside the elevators identifying the twelve parks in the neighborhood named for outstanding African American leaders who lived here.

Opposite the elevator doors Doggett created one more mural called Ancestral Masks of Diversity, which honors the range of different ethnic groups of the CD, Native American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Mexican.

Just inside the main door of the building is a large concrete support that includes the door of the original bank vault and four intense works by Inye Wokoma. The next blog post gives more detailed discussion about these works.

Lawrence Pitre depicts African Americans as they get loans from the bank,

Ashby Reed used a palette knife to invoke the streets of the CD in a semi abstract composition.

Finally Lisa Myers Bulmash created collage portraits of the architect of the original bank, the new Liberty Bank Building, and all nine of the multicultural founders of the bank. These collage portraits include a volume of an encyclopedia at the center, inset with a oval metal coin purse opening with varying images of the Statue of Liberty. The bow tie is a drawer knob. Bulmash is a master collage artist and every detail is meaningful from the fabric of the clothes to the background.

The commitment to art at the Liberty Bank Building is impressive. Al Doggett as Creative Director and Esther Ervin as Project Manager spent three years on the project, including their own significant contributions. So often these days art is an afterthought on new construction, or an afterthought, or non-existent.

In the Liberty Bank Building we have the start of the new Central District proudly establishing a unique presence,and pointing to the future.

Across the street, Africatown and others will be in charge of part ofthe full block to be developed. The original development here was part of the 1960s initiative to stimulate inner city growth.

This entry was posted on May 3, 2019 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Mary Coss’s “Groundswell” Tells About Salination and Climate Change

During a recent residency, Mary Coss was growing barnacles on Willapa Bay, the second largest estuary in the United States (over 260 square miles!)

During a recent residency, Mary Coss was growing barnacles on Willapa Bay, the second largest estuary in the United States (over 260 square miles!)

The artist described the process to me in detail: first she coated a wire mesh with cement snags to attract the barnacles, then dragged it over an oyster bed and left it for the barnacles to forage for food. Barnacles grow very slowly so a resident scientist kept track of the barnacles growth after she left.

Then she met scientist Roger Fuller † through the “Surge” project, a pairing of scientists and artists organized through the Museum of Northwest Art by former Executive Director, Christopher Shainin.

She learned that barnacles are the “canary in the coal mine” for water salination.

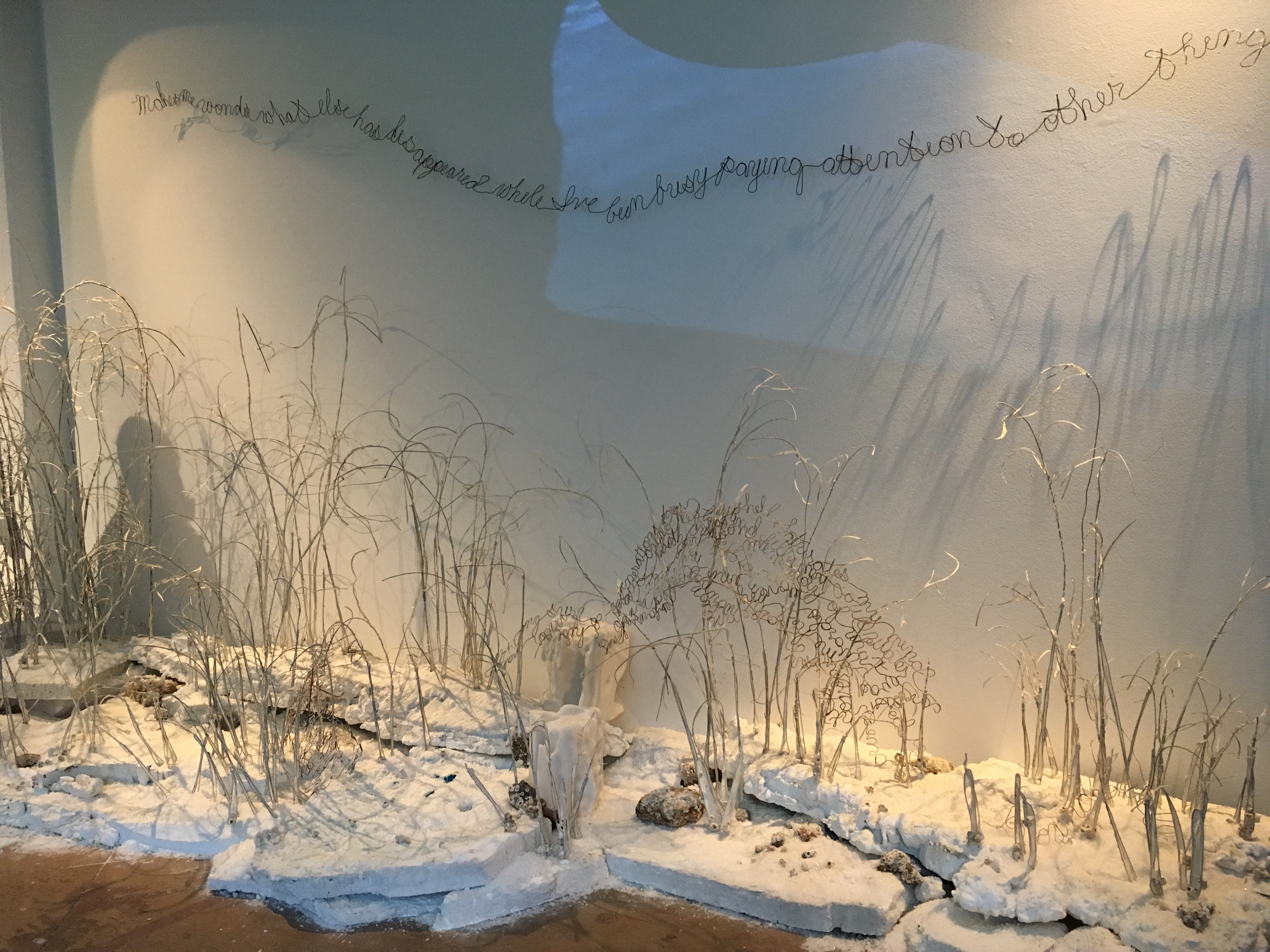

Groundswell, the last of a trilogy of works called Silent Salinity

(see her website for information on the other two), dramatically presents the first step of salination in the wild: barnacles attaching to fresh water sedge, a three sided grass.

Sedge likes freshwater and it is being starved as the fresh water rivers recede with decreasing rainfall leading to decreasing flow. This is a specific on the ground visualization of one manifestation of climate change .

Coss recreates that changing landscape in her gallery installation: the sedge is wire and paper pulp), and salt invades not only the sedge, but encroaches on us in the corners of the gallery.

Coss referred to it as a “dystopian landscape.”

Hanging above the salinated sedge you see a single line of writing in wire quoted from Roger Fuller’s essay on salination:

Silent Salinity: Net Loss

Scientist Roger Fuller’s pondering the state of the estuaries and the impact of global warming:

“I was out stomping through the mudflats in my hipwaders today, and discovered a bulrush ghost meadow. A small field of stumps, like a miniature forest clearcut. In the upper intertidal zone of brackish estuaries, tall, dense, verdant meadows of bulrushes grow, creating a tidal jungle of vegetation that hosts a myriad of critters and a far-reaching food web that spreads its strands through birds, crabs, and fish, even reaching as far as our dinner table.

But this was a ghost meadow I found, a slim reminder of a lush ecosystem once present, now vanished. Poking up from the deep, brown mud were stumps…3 inches tall, less than an inch thick, triangular, almost woody, stumps. Coated by years of mud and algae. A few sprouted barnacles. Easy to miss. Here and there a small plant poked up, but the tall, lush meadow was long gone.

There has been no meadow here for at least 8 years of my memory, and aerial photos confirm that I haven’t lost my mind, yet. I never noticed the change until today, the gradual retreat of a once lush ecosystem.

Makes me wonder what else has disappeared while I’ve been busy paying attention to other things? Perhaps that first barnacle was a sentinel of change, marking a salinity threshold silently crossed as the interplay of river and tide shifted. Or was it a shift in the food web, a small change in some quiet, unobserved corner of the complex web of life in which the bulrush is enmeshed?

It reminds me of the idea of “shifting baselines”…we think what we see today is the way it’s always been, when in fact things are slowly shifting and changing, right beneath our rubber waders. Without data, we have no sense of what we’ve lost, of what we’ve gained.

Far up the shore there is still a remnant of marsh, pinned against the dike with no place left to shift. How long will this remnant last? Will anyone notice when this meadow too slips away, when it becomes a ghost meadow?”

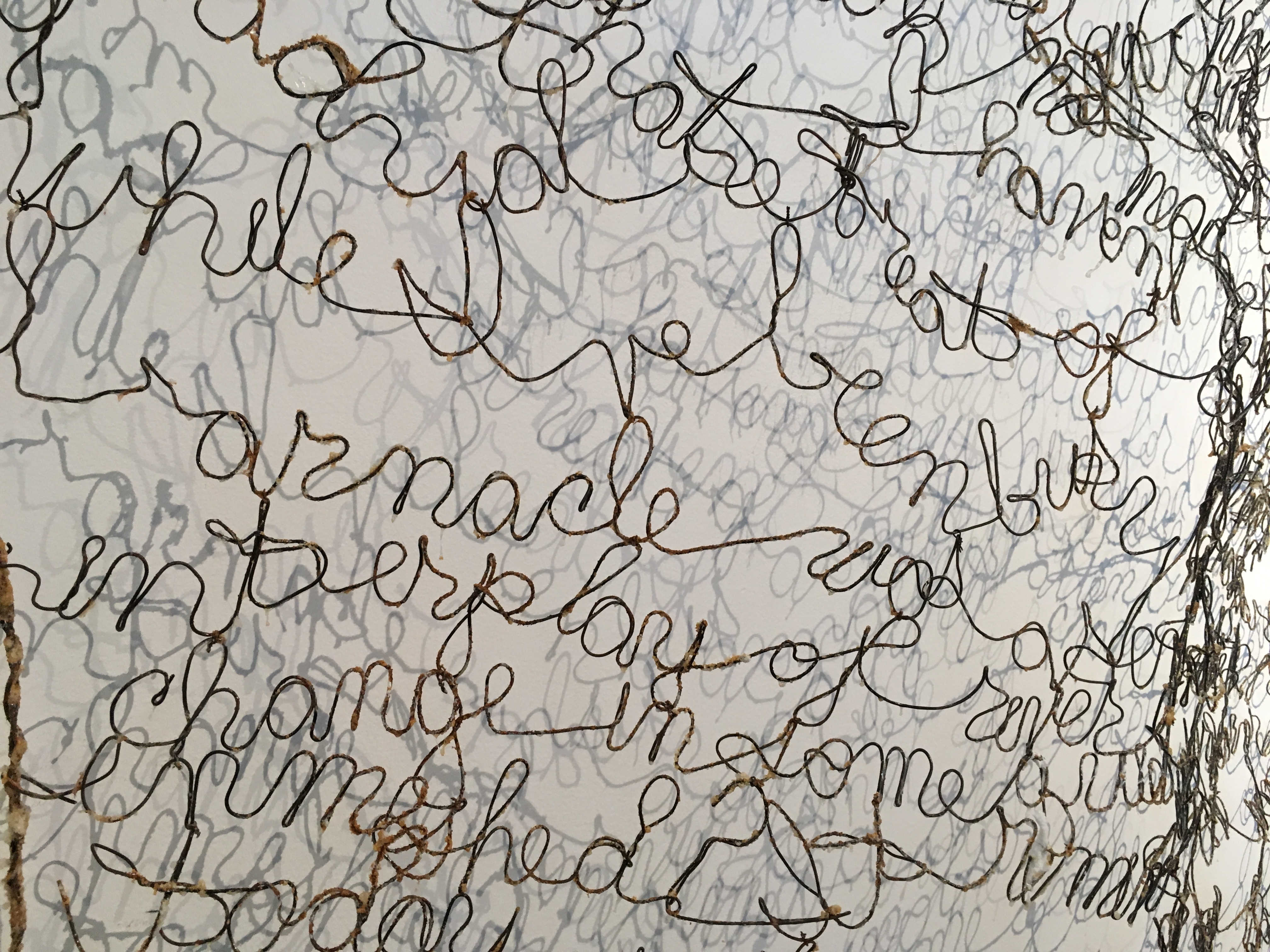

The entire poem is written in wire on the end wall. Here is a detail where you can read the word “barnacle”

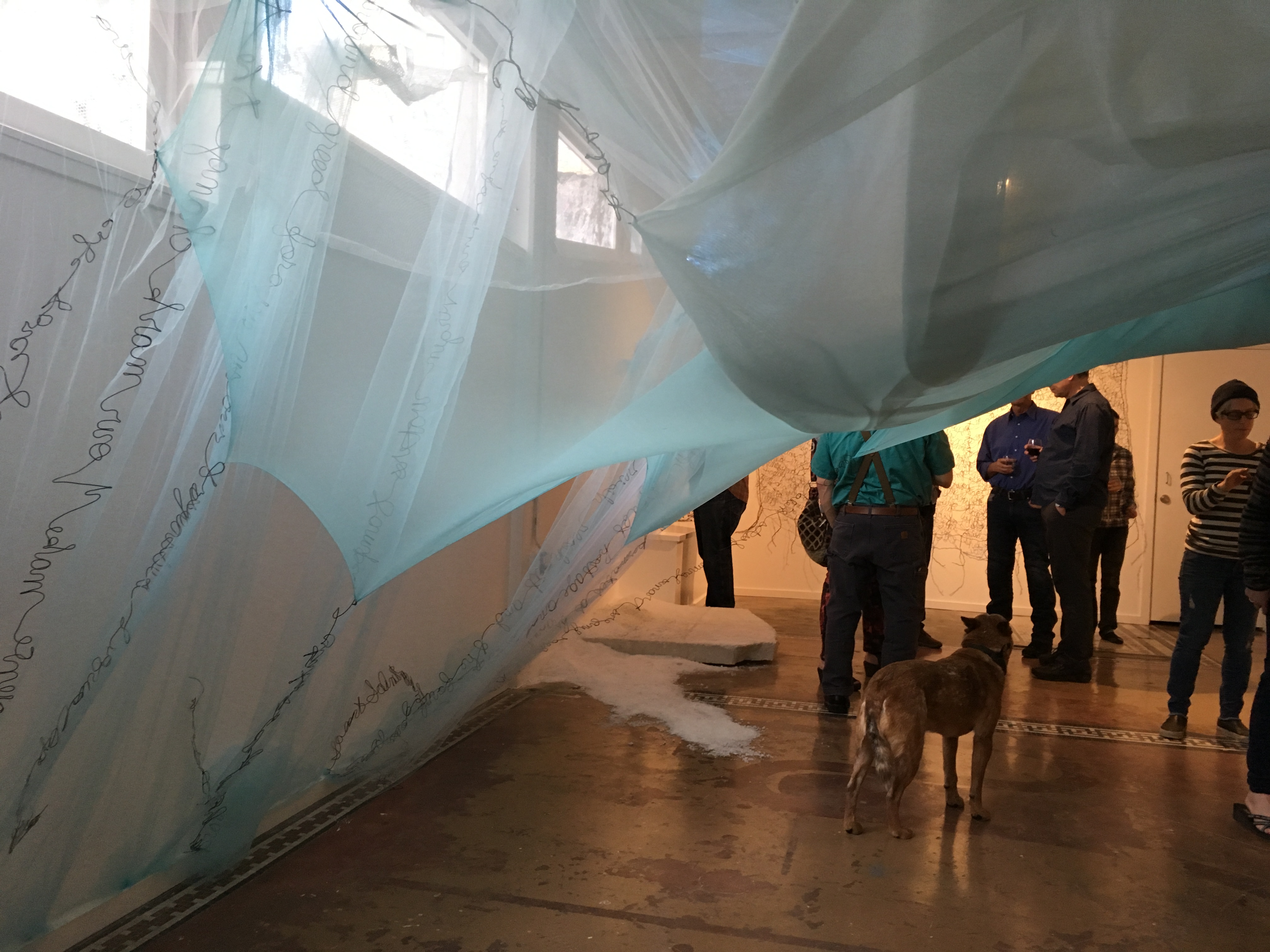

In addition to the salt encrusted sedge, and wire poetry, the installation includes a large wave which Coss described as “nature itself coming through”. The wave is manifested in a large structure of wire hung with billowing blue fabric. On it the artist projected flowing water. The wave seemed to be actually overcoming us in the gallery as it descended from the ceiling and, at the same time, the salt is spreading toward us on the floor.

The second image is the view from the window on the street. We see a salt encrusted screen and the wave. Coss inserted wire writing with her own poetry into the wave.

Coss succeeds in giving us what she calls a “visceral” reaction to climate change. The salt makes the huge story of climate change and global warming intimate. Perhaps that is because we all know salt, it is both physically part of our bodies, and a substance that we experience daily in our lives.

We also know that too little can kill us and too much, as we see in Groundswell, can also kill.

‡Scientist Roger Fuller works at the Skagit Climate Science Consortium and is a spatial ecologist with Western Washington University’s Huxley College of the Environment. He has expertise in estuarine ecology, restoration ecology, climate change impacts, climate change adaptation, and decision-support tools.

PS Read the book Salt: A World History by Mark Kurlansky to really understand how crucial salt has been historically.

This entry was posted on March 23, 2019 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.