Protesting Detention for Activist Leaders, Asylum Seekers, and ICE victims

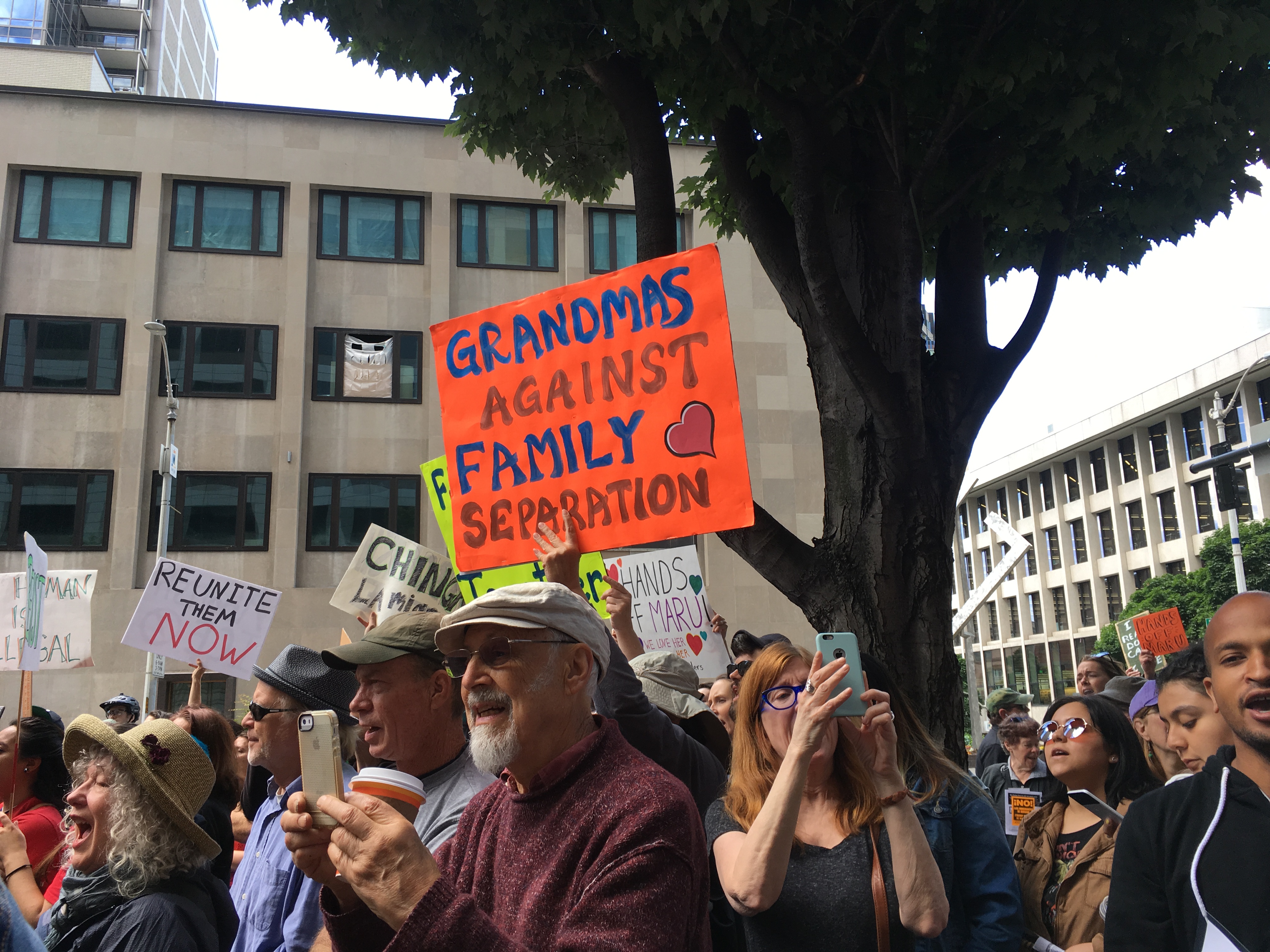

Last week was a big week for protest, but we are just beginning! We have to keep on, keeping on. Immigration as we are all focusing on, is the foundation of our country. On the eve of this 4th of July, I want to speak of some of the powerful support that immigration is receiving from we the people, at the same time that the administration is gaining more power every day. We have to stay in the streets as much as we can. Everyone.

So our first protest was to support Maru Mora Villalpando, who is the articulate and generous spirited leader of the Northwest Detention Center Resistance. She was served with a notice to appear at a Deportation hearing at her home in Bellingham, not long after the beginning of the year. It was during the time that the Dept of Licensing was cooperating with ICE.

One of Maru’s great strengths is that she constantly reminds us of all the people who do not have her prominence, who are suffering the threat of deportation, the nightmare of detention, and the separation of their families. We need to stand up for every one.

This was her second hearing, in a nationwide policy to deport leaders of the resistance to illegal actions.

Almost 200 people gathered on the street outside the building in which ICE holds their hearings for deportation. Maru spoke to us before she went in, with no idea if she would come out.

As her hearing was going on, we heard from local activist leaders, who held a People’s Tribunal and spoke of the evils of ICE, suprematist racial profiling, the public private partnerships of ICE, the for profit dehumanization of people of color throughout our history ( slave trade, Indian removal, Asian American detentions- which were about grabbing valuable farmland), They reminded us that the first detention center was created in 1882 to hold migrants from China (Angel Island),

They reminded us the gigantic profits that GEO, the private company that runs so many detention centers and prisons makes, from 42 to 144 million increase in one year and even the “alternatives” to detention are for profit ( ankle monitors have to be paid for with a monthly rent, foster care generates income also)

Our local campaign against spending millions on a new youth jail is connected to this opposition to incarceration for black and brown children.

The People’s Tribunal demanded the close of NW Detention Center and all detention centers and found ICE guilty of violating basic human rights. They called on Martin Selig to stop renting space to ICE and Governor Inslee to stop all collaboration between state agencies and ICE.

But in fact, we are all guilty, because any money we have in retirement accounts is probably invested in GEO ( look into it)

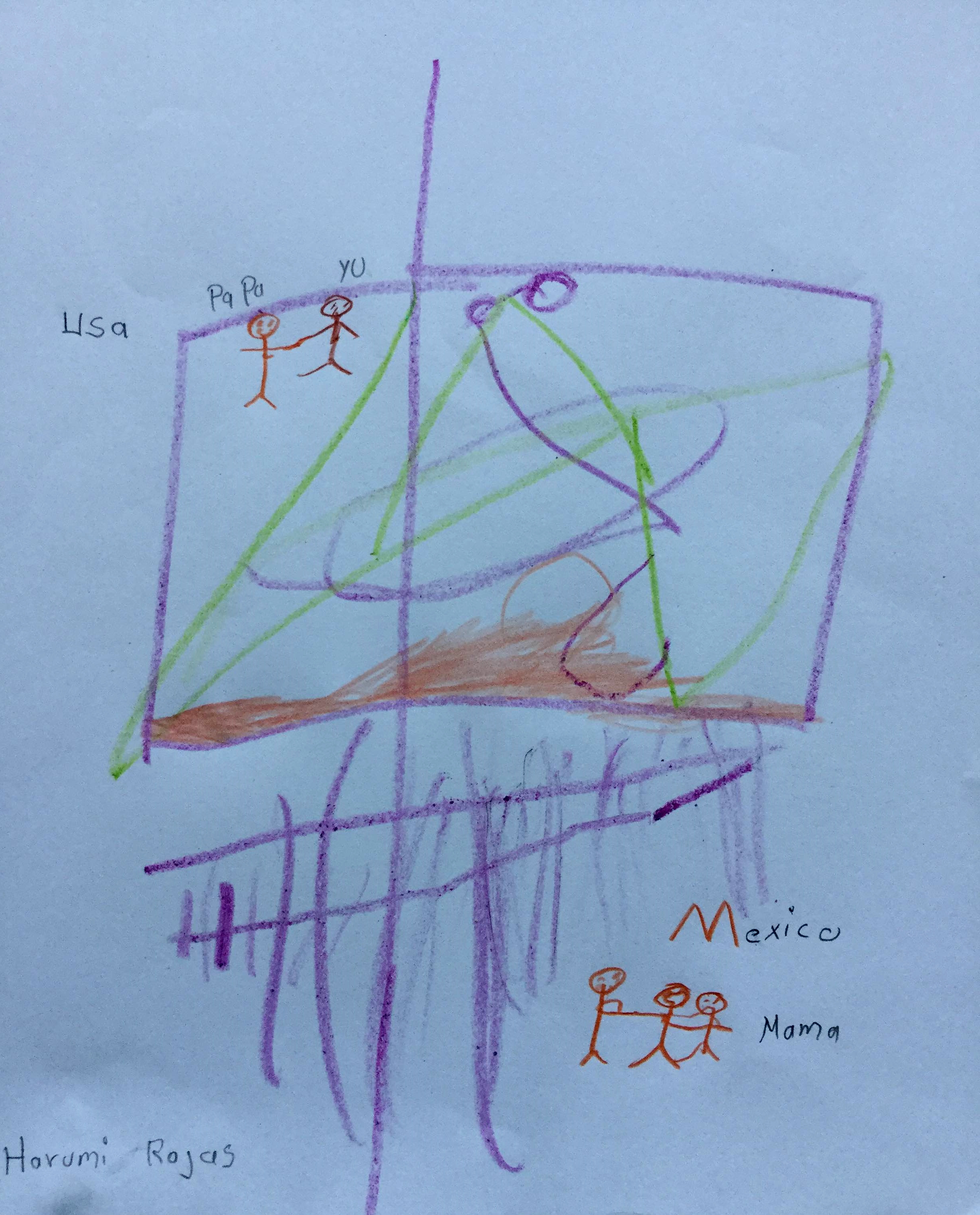

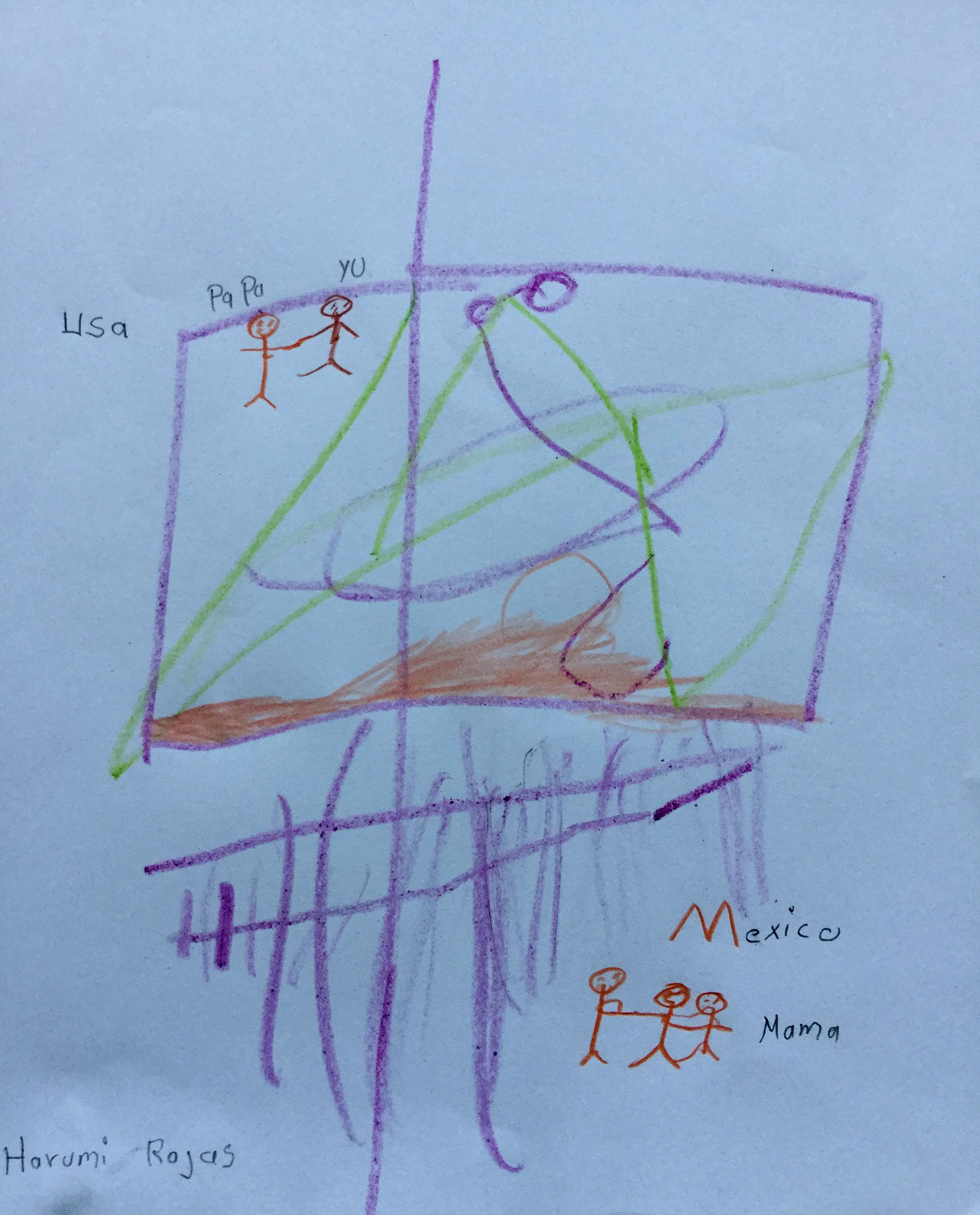

When Maru came out, she had a good result, her case was continued until January 2019 and because her daughter will be 21 in July, she can apply for a green card. But her words addressed the families in the hall awaiting hearing, the children crying, those who do not have a lawyer, or any opportunity for relief. As the ghastly administration tightens or eliminates all options for asylym ( Recently domestic violence and gang violence were eliminated as grounds for asylyum) , the situation requires our constant protest. We need to think of all of the undocumented immigrant families who give so much to our country and are now being so horribly torn apart. Here are a few children’s drawings.

s

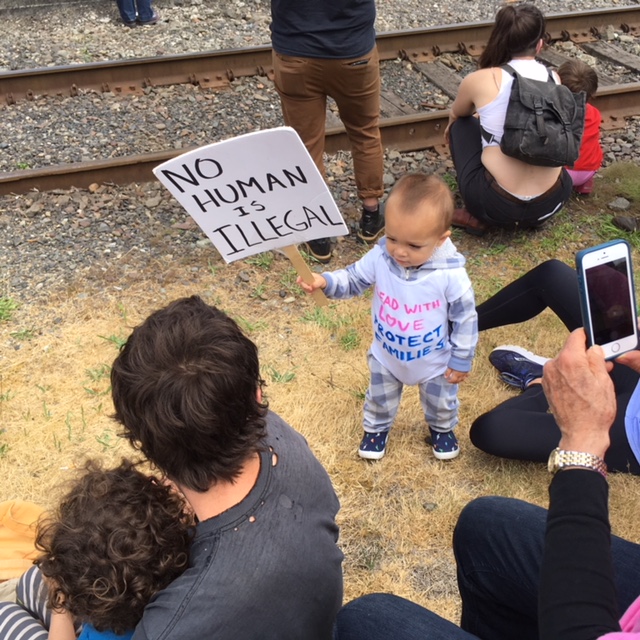

On Saturday, we joined 10,000 people at the Federal Prison near Sea-Tac, to protest detention, some of the thousands of parents separated from their children are being held there ( although they said if they are transferred to the Northwest Detention Center, they are treated much worse). And of course there were thousands and thousands protesting all across the US, although barely reported in the media except for Democracy Now.

And on Sunday we joined the extremely energetic protest outside the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma. It was led by the Northwest Detention Center Resistance. We heard from a mother of five children whose husband was in the detention center, leaving them in financial straits. He has very serious health problems that they delayed in treating causing more health problems.

We heard from a brave mother who had an “ankle monitor” speak of the nightmare of conditions there and we heard from a Cuban, ( they no longer have special status), who was detained inside for many weeks.

I have been to many of protests at the Northwest Detention Center, and this was the most successful in chanting long and loud outside the center ” you are not alone” ( in spanish), challenging employees entering to quit their jobs, and staying for a long time.

The Occupy movement is still alive and well, and is now Occupying ICE, in Philadelphia, San Francisco, and nation wide, particularly successful in Portland, where they managed to shut down ICE for several days.

KEEP ON, WRITE LETTERS, PROTEST

This entry was posted on July 6, 2018 and is filed under Uncategorized.

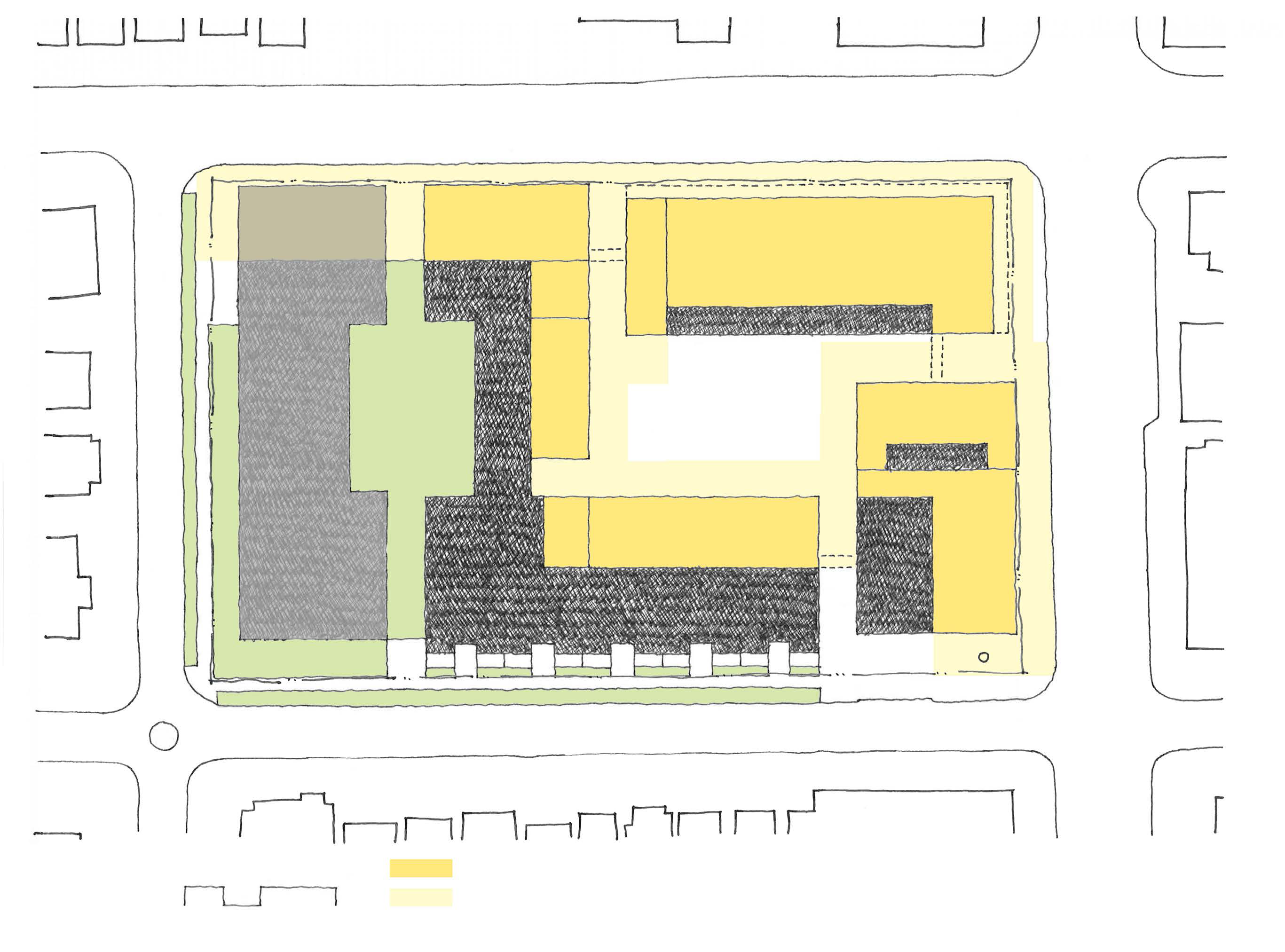

Gentrification in the Central District: A Snapshot

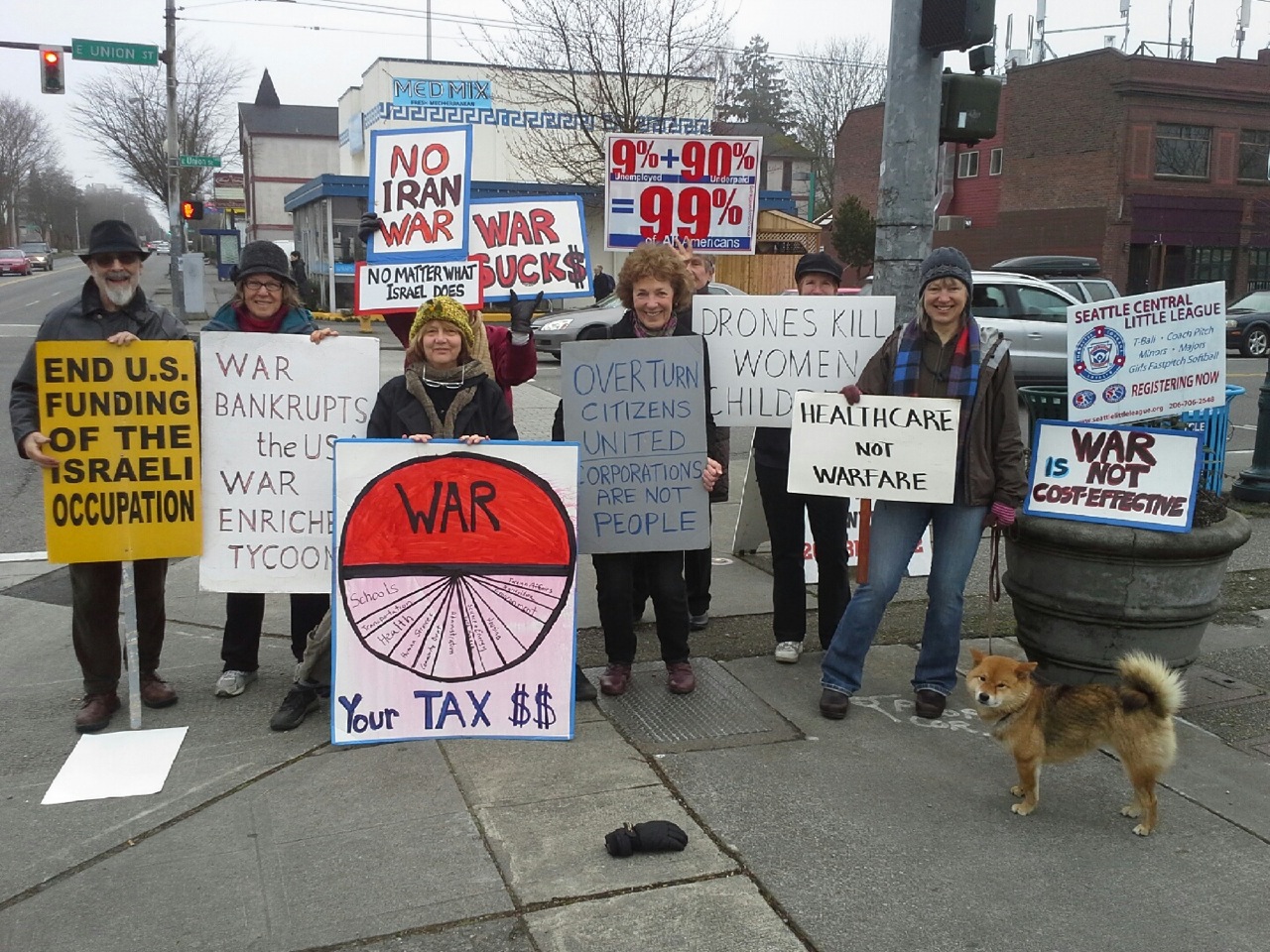

This week we went to a meeting about a development on the corner of 23rd and Union ( top as it looks now), near us. It is the South east corner, an historic corner owned formerly by the Bangasser Family, known as Midtown Center. Above is a gathering from a few years ago demonstrating this crucial corner as a gathering place.

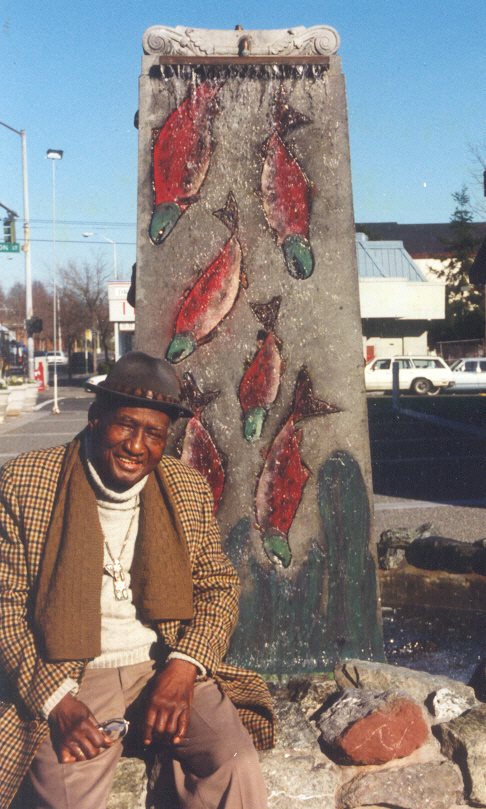

It was a starting point for a Black Lives Matter march also (below first photograph) . Second photo shows the famous Fountain of Triumph by James Washington originally located there.

It was sold last year to the Lake Union Partners, who declare “Our focus on neighborhood context and the user experience is always at the forefront of design decisions. We strive to create viable financial strategies for each individual project based on those design drivers, including special emphasis on the street level experience – making sure our retail tenants complement the unique profile of each project.”

Well they have not encountered a neighborhood like ours, with its organized Africatown, and many articulate African Americans speaking up for the historic neighborhood.

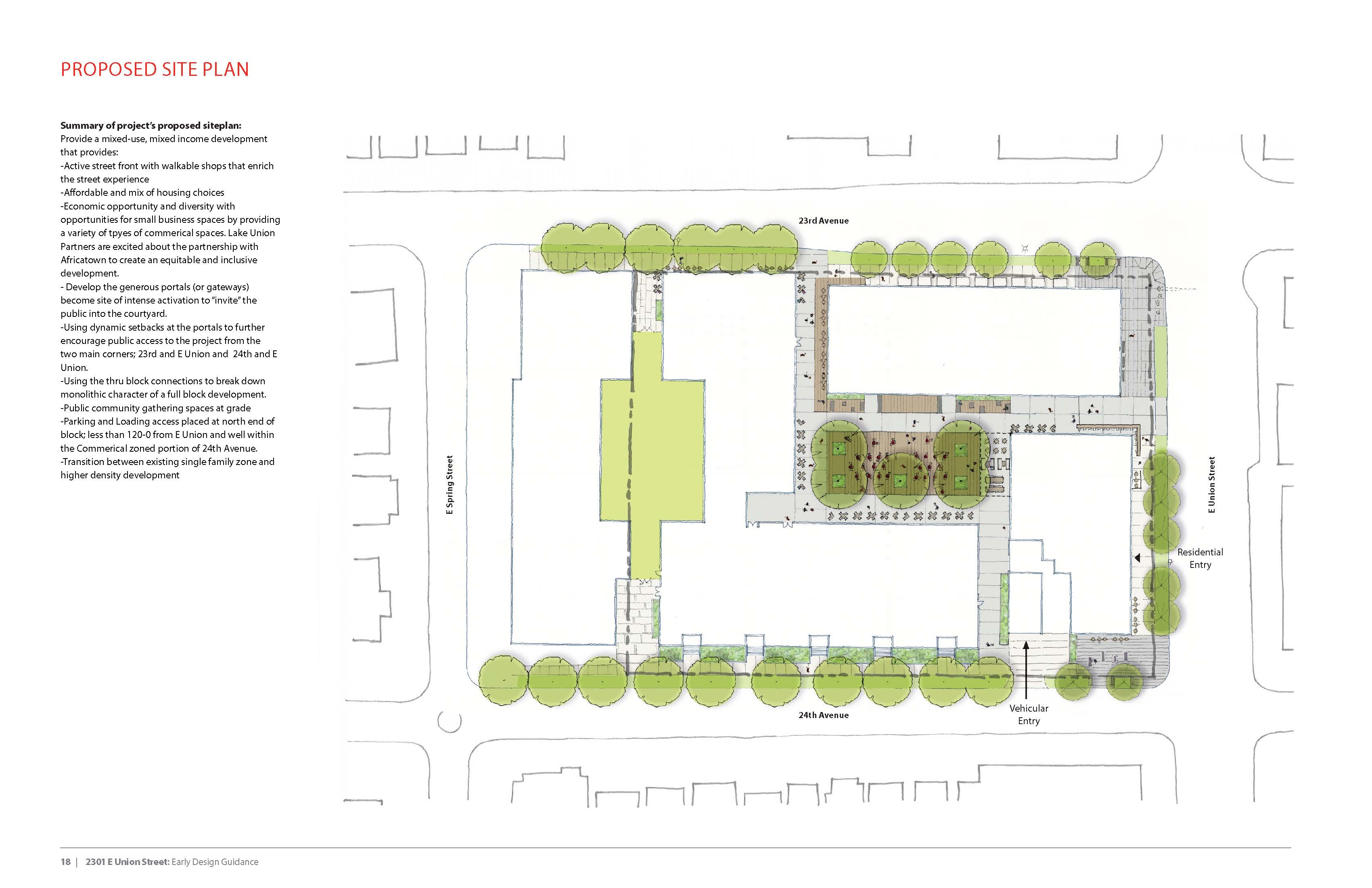

Even before they started their presentation, Omari Garrett and several others started objecting to the fact that although one quarter of the block had been sold to Africatown to develop, it became a de facto act of segregation to have a separate development. You can see the Africa Town portion is on the far left in drawing, but in the presentation it was omitted entirely. The LUP development stopped at a semi circle ( above it is a rectangle, that was “was going to be a shared private space with the other part of the development”

Furthermore LUP was romping ahead with big funds and big access to process, while the other building was moving slower because of lack of experience. Why did not LUP do more to enable the other section to move forward was one question??

They have already developed two other corners at this intersection:

Above is the Northwest corner, below is the Southwest corner. Across from the second photograph you can see the third corner that was the subject of our meeting. Not bad looking buildings, but definitely designed for the well off.

This corner was orginally developed as an urban renewal zone in the 1960s with all black businesses. Tom Bangasser, who spoke at the meeting, spoke about recruiting the post office and a state liquor store which could not be red lined, in order to have anchor tenants.

He has a long time commitment to supporting African American businesses and also commissioned James Washingon ‘s beautiful fountain for the property.

That fountain was on 23rd just south of Union, it will now be on 24th and Union in a small private park, an idea that was much objected to by many people there. Indeed it was originally a gathering place and a focal point, now it will be a “quiet area”.

Before the development of the Southwest corner, a major public art work linked to the web told stories of the “corner”

Another aspect of the corner that I am connected to ( gentrifying white person) is weekly anti war demonstrations there for about ten years.

The city put in a public sculpture only a couple of years ago as part of the 23rd ave improvement project. It is by Martha Jackson Jarvis, from Washington, DC. She is honoring the community.

So back to SLU rhetoric

Here is more ( above is Patrick Foley, Principle of LUP who presented their plan):

“Our management team relies on a solid understanding of market fundamentals to direct our investment strategy and our extensive network and brand allow us to source considerable off-market opportunities.

LUP develops strategies customized to specific real estate asset classes. We recognize there are opportunities for our investors at any stage of a real estate cycle. Primarily, our partners are local family companies and we tailor each project to meet their short and long term goals.

We develop with integrity and invest in the community’s future. We are engaged in vibrant neighborhoods and have a knack for finding up and coming locations. We tend to invest in these areas before other developers – discovering livable, walkable and thriving communities.”

I went to one of these type of meetings about the Paul Allen development at Jackson and 23rd. Well off white people presenting to impoverished locals. Proudly those presenters declared they were incorporating an African American motif in order to “honor the history of the neighborhood. ” In that case, people said, what about all the other people and ethncities here?

In the case of 23rd and Union, one question was, in what way will your building reflect African American references. Across the street, another new development by Africatown Community Land trust, includes art work by major African American artists from the neighborhood. It is the real deal. It is on the site of Liberty Bank first black owned bank west of the Mississippi, so this site has a lot of significance. They also own the 25 per cent of the 23rd and Union site.

LUP touted their public square in the middle of their development, with access to the street. Where those green ovals are ( now reduced to one tree). The idea is that all along the street level of these building will be lively little shops. Of course given our weather, how much time people spend outside there is a question. Another question for me is that “Ike’s” pot shop is right across the street, and this has been a corner for drug use for a long time. I wonder if that will be the main function of this public square.

It depends on lots of lively little cafes and stores to make it a draw for people. They will undoubtedly be little yoga/pilates studios, ice cream stores, and overpriced single product stores such as those filling up Capital Hill.

The real center of energy not far from that corner is Chucks Hop Shop at 20th and Union ( that’s Chuck there) , a wildly successful family oriented place.

Beer, ice cream and food trucks.

Also Katy’s cafe is a major center of action across the street ( lucky me this is my corner).

These two businesses together plus our 2020 bike shop, Central Wellness Chiropractor, Central Ice Cream, Central Cinema and Communitea Kombucha factory, make for a vibrant block.

I wonder if LUP can make these type of buisnesses happen around their central plaza. I fear their rents will be too high. The reason these businesses survive is because the people who own the buildings are not greedy and have committed to keeping ordinary small business owners here. None of them are owned by African Americans though. The ice cream store is Filipino owned. Chuck’s is owned by an Asian American. Obviously, there is a good reason why Africatown is standing up for African American businesses and presence. When we first moved here in 1998, there were quite a few.

I fear for our small businesses all over Seattle. Downtown they are all being wiped out invisibly inside old buildings.

We heard about Bernie Utz Hats, that is only the tip of the ice iceberg. My hairdresser has been displaced twice in ten years because each of the entire buildings he had his small business in on fourth avenue was bought by big corporations and all small businesses displaced. ( The jewelry on street level has been given a temporary reprieve. )

Anyway here’s hoping LUP can create the vibrant plaza they are hoping for.

PS and guess what, Africatown is showing them the way!! Here is the newly repainted plaza as of last Sunday. And a link to their mural project “Coming Soon” as described in the Seattle Times.

This entry was posted on July 2, 2018 and is filed under gentrification central district, Uncategorized.

Greenpeace Arctic Sunrise

We had the thrill of touring the Greenpeace Arctic Sunrise ship on Sunday. I am holding the “Wave of Resistance #stop the pipelines Orca solidarity bracelet they gave us.

It has just come back from Antarctica where it took scientists to study the way to create a marine protected area in the midst of the drilling and resource extraction that is escalating at both the Antarctic and Arctic in the face of the melting of the polar ice caps. On the ship we learned that it was an ice breaker that breaks ice by pounding down on the ice with the rounded hull! That means it is very tippy in general ( they nicknamed it the “washing machine”). The ship actually dates to 1975.

Here is a description of their history from Greenpeace website:

“The Arctic Sunrise’s first trip took it to the North Sea and the northeast Atlantic, where Greenpeace documented marine pollution by oil from offshore installations. Since then it has worked everywhere from within 450 miles of the North Pole, to Antarctica’s Ross Sea, and has navigated both the Congo and the Amazon.”

There have been major push backs against the important Greenpeace missions.A Greenpeace boat was bombed and exploded by French scuba divers when it was protesting nuclear testing off New Zealand.

They were boarded by Russian armed militia and the entire crew imprisoned for several months, released at the beginning of the Sochi Olympics in 2014 (when the Pussy Riot protesters were also released).

They carry 35 -40 people from many countries in the world on their trips.

Our tour included the control room with both old fashioned and up to the minute controls.

We also had a presentation on the resistance to the expansion of the tar sands pipe line in BC ( the one the Canadian government just declared that they were buying), as well as facts about the production of tar sands ( vast amounts of fresh water to burn tar out of sand, then toxins to make it flow in the pipeline. A spill will lead to a massive die off in the sea as it is so dense nothing can be recovered and nothing can survive.

Here you see the cut out banner added for the Seattle stay “Chief Seattle is Watching”. They are going on from Seattle to Tacoma to support the protest of the liquified “natural” gas facility there that is being built without a permit on the Puyallup land by Puget Sound Energy. Puyallup Tribe is leading the protest. Puget Sound Energy is “owned by an Australian utility claiming to be a leader in green energy, but 60 percent of its supply comes from coal and “natural gas”, most of it fracked. Gas has been called a “Bridge” fuel in the transition to renewables, but methane released during extraction and transport means its as bad for the climate as coal because methane has 80 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide” quote from brochure handed out at Arctic Sunrise event . It ends are you in the blast zone? find out at Frackno253.com . It looks like the entire Northwest Detention Center is certainly in the blast zone.

if you want to see the industry PR, here is a link

and then you can text Governor Inslee to protest it.

This entry was posted on June 27, 2018 and is filed under ecology, economic imperialism vs democracy, Uncategorized.

“In the Fields of Empty Days: Intersections of Past and Present in Iranian Art,”

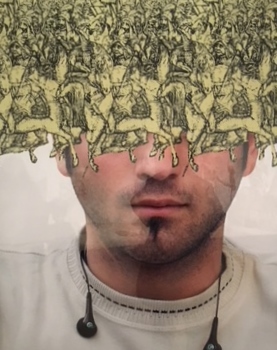

“In the Fields of Empty Days: The Intersection of Past and Present in Iranian Art” at The Los Angeles County Museum is a show on a crucial topic. Although much of the work is contemporary, note that the title does not say that. Tirafkan’s image speaks volumes of the intersection of past and present that is the theme of the exhibition: the young man is blinded by the warriors of the past, his earbuds hanging around his neck.

As curated by Linda Komaroff, it includes photography, both historic and contemporary, drawing, video, valuable manuscript pages, historical paintings, sculpture, and animations. Only a few of these artists have been shown in the US before ( note the Gray Art Gallery in New York City has an outstanding collection of Iranian modern art)

from the Series” Underground”

The curator’s decision to have absolutely no informative labels was slammed by the Washington Post critic. I disagree with that point of view. It was intriguing how much we engaged with these extremely political works without information. We could understand the critique in the work without polemic. Look at the work above. From the title it is obvious what is happening, the British Ambassador holds a leash and a whip, the Shah is wearing female clothes.

Many of the works are in the permanent collection of the museum, shaped by the same perspectives seen in the exhibition. In a brilliant review published in Iran, the critic Mahsa Farhadi reveals the Orientalism that underlie the curatorial theme of past and present as well as the choice of works in the collection and in the exhibition. She sees the exhibition as overgeneralizing those categories of “past” and “present.”

The title of the exhibition is a quote from a modern poet Mehdi Akhavan-Sales’s famous poem, “The Ending of Shahnameh.”

Shahnameh, (Persian: شاهنامه )“The Book of Kings”), the famous 50,000 line Persian epic poem by Ferdowsi written in the tenth and eleventh century. Bringing back Iranian history and the Persian language, it tells the myths and history of Persia from the dawn of time to the Islamic conquest in the seventh century. Illustrated versions of the Shahnameh represent the finest examples of the art of the book. The quote from the modern poem is

“Oh, henceforth we are

Like hunchbacked, old conquerors.

On the ships of waves, sails of froth.

Our hearts bound by the memory of the lambs

of splendor, in the fields of empty days,

Our swords rusty, worn out, and weary.

Our drums, forever silent,

Our arrows, broken winged.

We are the conquerors of the cities gone with the wind

We relate the forgotten stories

In a voice too weak to come out of the chest.

Nobody will pay attention or spare a copper for our coins

As if they are of a foreign king. Or, a prince whose dynasty is overthrown.

Siamak Filizadeh’s Underground , a series of huge photographs opened the exhibition, filling a long wall and a short wall. They feature the 19th Shah Nasir al-Din Shah, imagined as ruling an underground city. This Shah, like the Ottoman shahs of this time, engaged with Europe, and participating in modernizing. Reference is made to these trips in various ways, but the overall sense of the series is derogatory. The Shah appears ridiculous in Coronation, for example in which the throne is held up by two pairs of red stockinged legs and the shah is holding a rabbit.

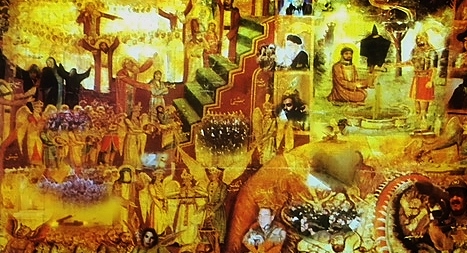

The next artist who mesmerized me was Shoja Azari. He inserts video into a wall size projection of a manuscript page and a “coffee house painting” .

Here you can see some black and white figures in the center, as well as a nearby contemporary person. And near the upper right the famous Abu Ghraib image of torture is represented.

Another bizarre and fascinating combination of references appears in this propaganda poster from World War II based on the Shahnama with Goebbels as Satan as cook as monkey. It is drawn from an actual event in the Shahnama when Satan embeds himself as a cook at the court then through bribery enters the shoulders of the Shah Zahhak as serpents, causing the Shah to do many evil acts throughout his reign.

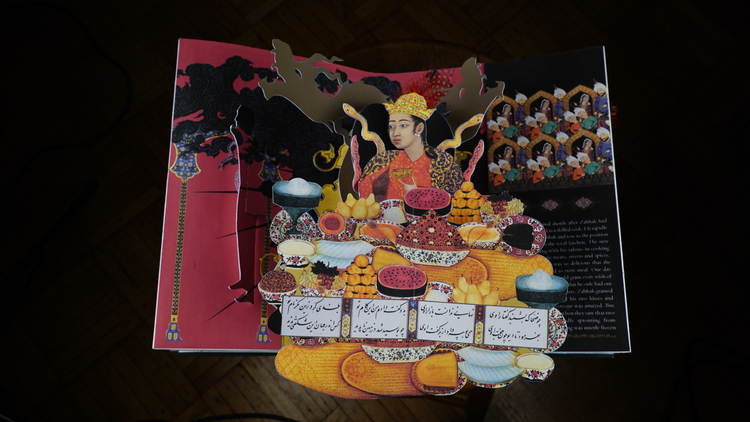

There is a wonderful cut out paper pop up of this story. Cut out artist is Simon Arizpe, amazing pop up book artist.

One of my favorite pieces was Yasmin Sinai, a large ensemble of cardboard figures, almost life size recounting the story of a female warrior from the Shahnama.“But one of those within the fortress was a woman, daughter of the warrior Gazhdaham, named Gordafarid. When she learned that their leader had allowed himself to be taken, she found his behaviour so shameful that her rosy cheeks became as black as pitch with rage. With not a moment’s delay she dressed herself in a knight’s armour, gathered her hair beneath a Rumi helmet, and rode out from the fortress, a lion eager for battle. She roared at the enemy ranks, “Where are your heroes, your warriors, your tried and tested chieftains?”

There were not many women in the exhibition. Aside from Yasmin, they were familiar, Shirin Neshat and Shadi Ghadirian for example we know well.

Also familiar were Parviz Tanavoli, although best known as a sculptor and here seen in a painting and weavings.

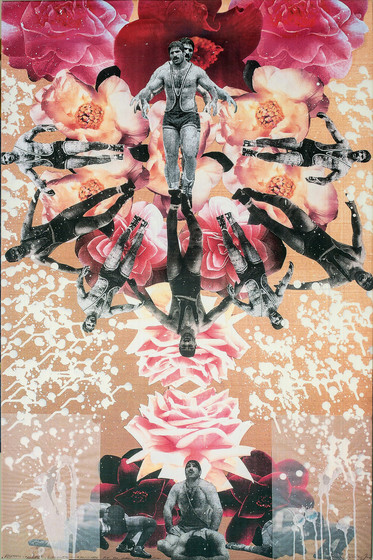

This work by Fereydoun Ave was also familiar, another reference to both the male wrestling tradition and the Shahnameh epic hero Rustam.

The theme of male wrestling appeared repeatedly.

There were also stunning works by other well known Iranian modernists such as Charles Hossein Zenderoudi and Khosrow Hassanzadeh as well.

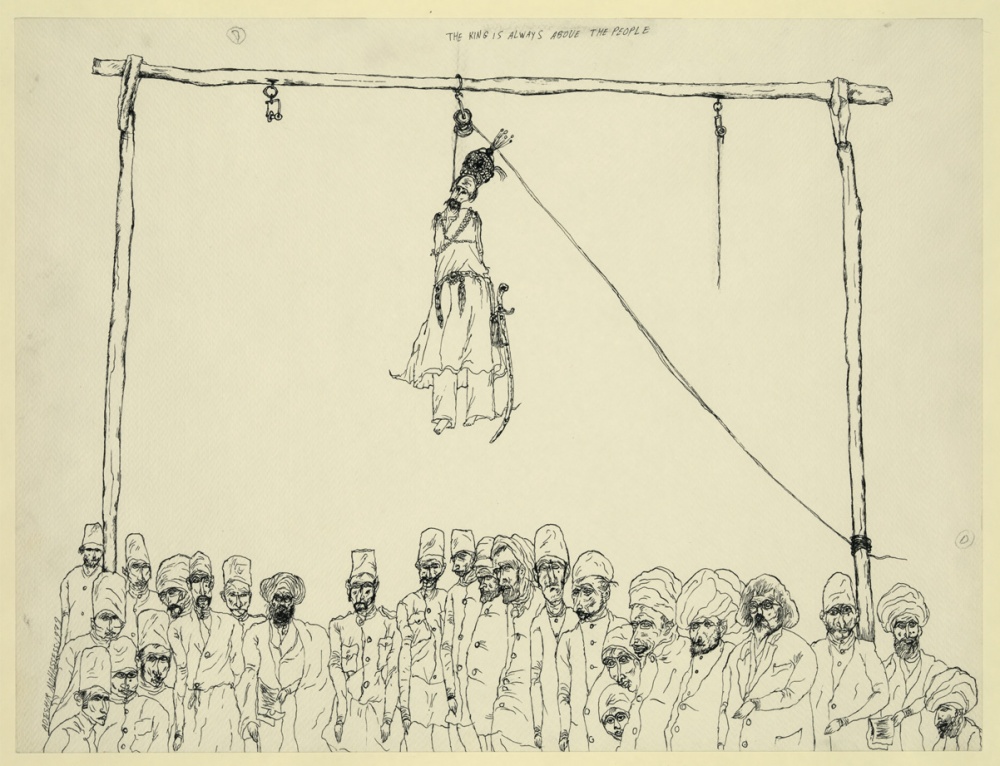

The juxtapositions of various epochs of art continued in the intricate and sardonic drawings of Ardeshir Mohassess, in a series from the 1970s borrowed from the Library of Congress! He uses late Qajar imagery to make reference to the Shah’s demise in the 1979 revolution.

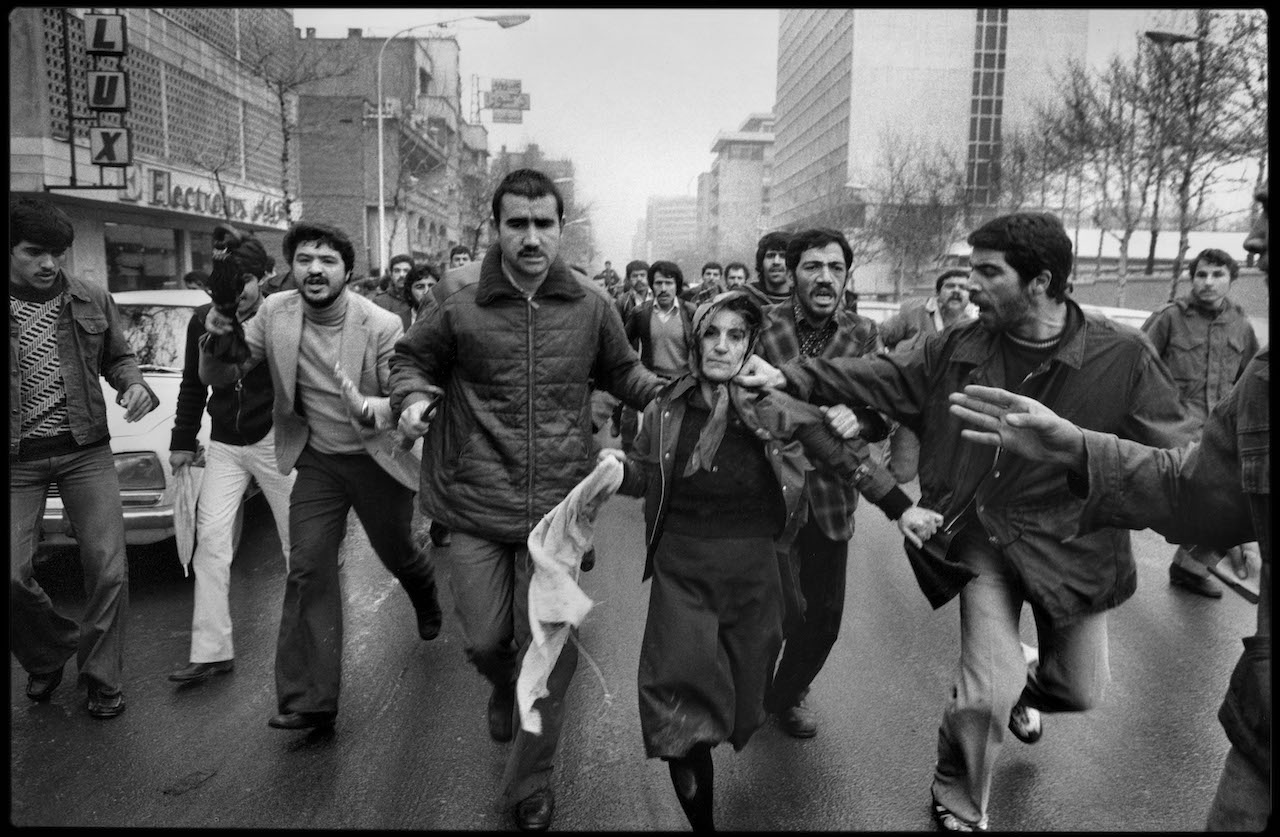

After a demonstration at the Amjadiyeh Stadium in support of the Constitution and of Shapour BAKHTIAR, who was appointed Prime Minister by the Shah before the left the country, a woman, believed to be a supporter of the Shah is mobbed by a revolutionary crowd.

See also ABA1979006W00011/05AR

That revolution and its convolutions came alive in the famous photographs of Abbas (above) , Kaveh Golestan, and Maryan Zandi. We see both the protests of the Shah and his supporters in mass crowds and up close.

As with all revolutions ( such as the Arab spring) , the joy led to tragedy, as the Islamic leaders followed an oppressively conservative direction subsequently challenged by the same people who were happy at the departure of the shah.

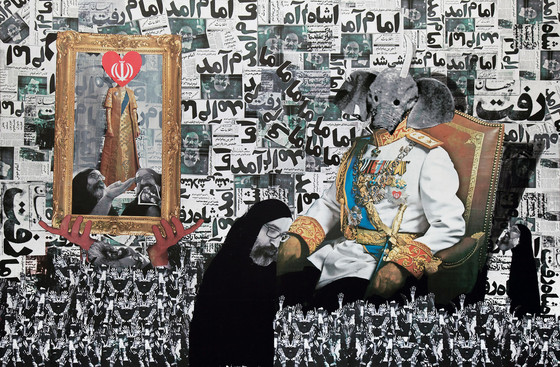

One of my favorite images that focuses on the craziness of the Revolution is by Ramin Haerizadeh

Perhaps that is why the curator chose to include fabulous animations.

Or the imaginative work of Makekeh Nayiny

Although they also make reference to early myths, the metaphors of contemporary life and politics are obvious. In All in the Pink, Nayiny gives us a child in a grotesque mask, a demon mask, a reference to the demons defeated by the hero Rustam in the Shahnama. Now though this disturbing masked child challenges us to wonder who the real demon actually is (you can see the historical depiction in the wallpaper in the background).

This subtle show offered us new insights into Iran. Most of the art works were direct satires or protest masked in historical and mythical themes. The photographs from the time of the revolution we now see in the light of subsequent events as deeply sad and ironic.

Given the one dimensional knowledge that most people in the US have of Iran today, visiting this exhibition provides an opportunity to understand the complexity of Iranian history as well as its present moment. The resonant phrase “In the Fields of Empty Days,” invokes a desolate end to an empire that can apply to not only the situation in Iran, but also elsewhere on the planet as misguided policies kill, torture and brutally damage humans and the earth.

Full Photo credits:

Sadegh Tirafkan The Loss of Our Identity no. 1 Boy 2007, fromthe Series, The Loss of our Identity, 2007, chromogenic print, Brooklyn MuseumMuseum Collection Fund, by exchange

Siamak Filizadeh, The British Ambassador, The Coronation and Anis al-Daula from the series “Underground”, 2014, inkjet print, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by Kitzia and Richard Goodman through the 2016 Collectors Committee, © Siamak Filizadeh, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Shoja Azari The Day of the Last Judgment (Coffee House Painting,)

2009 video projection, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, gift of Leila Heller

Kevin Evan Marengo, Ahriman-Goebbels disguised as Zahhak-Hitler’s cook causes serpents wiht the faces of Mussolini and Tojo to grow out of his shoulders, 1942, offset lithograph on paper, LACMA purchased with funds provided by Shidan Taslimi

Yasmin Sinai, The Act of Gurdafarid, the Female Warrior, 2015 cardboard paper glue, LACMA, gift of Lynda and Stewart Resnick through the 22017 Collections Committee

Parviz Tanavoli, Lion and Sword III, 1976, Bijar weave, 62 1/4 × 91 in., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Hope Warschaw through the 2018 Collectors Committee, courtesy of the artist, © Parviz Tanavoli, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Fereydoun Ave, Untitled from the series Rostam in Late Summer—Revisited, 2009, inkjet print on canvas, 59 1/2 × 39 1/2 in., Mohammed Afkhami Foundation, Switzerland, © Fereydoun Ave, photo courtesy of Janet Rady Fine Art

Ardeshir Mohassess, The King is always above the people from the series Life in Iran, 1978, ink on paper, Prints an Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Kaveh Golestan, The Shah Left, 1979, printed 2015, gelatin silver print, 24 × 30 in., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of the Estate of Kaveh Golestan, © Estate of Kaveh Golestan, digital image © Museum Associates/LACMA

Ramin Haerizadeh, He Came, He Left, He Left, He Came, 2010, mixed media and collage on canvas, 78 3/4 × 118 1/8 in., The Farook Collection, Dubai, © Ramin Haerizadeh, photo courtesy Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde

Malekeh Nayiny, All in Pink, 2007, dye coupler print, 47 1/4 × 35 3/8 in., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by Nina Ansary, © Malekeh Nayiny

This entry was posted on June 25, 2018 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Iran, Iranian protests, Iranian Women, Uncategorized.

Art and Politics in films at the Seattle International film Festival

Warrior Women is a gripping documentary about radical activist leader Madonna Thunder Hawk, and her daughter Marcy Gilbert. Thunder Hawk ran a school for youth that educated them about Native History in the early days of the Civil Rights movement. Thunder Hawk’s own story spans from the era of native boarding schools that stripped indigenous people of their cultures, to the Wounded Knee confrontation, Alcatraz Island sit in, and finally Standing Rock, in South Dakota. It is a remarkable story of persistence in the face of the difficulties of being a radical leader: arrest, travel away from her family ( or with her family to radical events), lonely nights on the road, dramatic confrontations with hostile opponents, and much more. What is most remarkable is that her daughter grew up in this atmosphere and herself chose to also become a radical.

William Kaysaywaysemat III

Bee Nation as in Spelling Bee documents the first Canadian First Nation engagement in the national spelling bee of Canada. It follows several young participants from their reservation life to the hotbed of a Toronto competition. The film begins with the youngest of the contestants preparing to dance in a pow wow ( see above , thus setting the stage for the intersection of traditional and white culture that this spelling bee represents. ( I wonder how white children would have done in a native spelling contest?)

Mohammad Bakri and his son Saleh Bakri as father and son (and real father and son)delivering wedding invitations in Nazareth

Wajib ( Palestinian). wajib refers to a muslim obligation, in the case of this movie by Annemarie Jacir, it refers to the act of personally delivering wedding invitations by men of the family of the bride in Nazareth. The movie weaves together many contemporary concerns about the situation for Palestinians as a father who lives in Nazareth and his son, who lives in Italy, forced to leave as too radical, deliver the invitations to relatives and friends.

As they do so, the issue of inviting the Israeli supervisor of the father raises enormous tension between father and son, as the son states the man is a spy. Many other issues and tensions arise between father and son, particularly the mother who has left the country, her two young children and her husband, years before. She is perhaps coming to the wedding perhaps not. Also hotly debated is the issue of leaving as an expatriot vs staying in Nazareth and being subservient.

The brilliantly filmed sequences of interior and exterior spaces in Nazareth convey both the constrictions of life there and the generous spirit of the people who live under those constrictions.

Falling ( Ukrainian) Falling is both literal and metaphorical in this film set in the Ukraine after the uprising that led the Russians to invade and take over the Crimea. It is always notable that movies from Europe move slower and are not about violence, but often about love. The two protagonists circle around one another, but ultimately fail to connect.

Razzia ( Morocco) Set in Casablanca, with the famous movie echoing through it, Razzia gave us the tensions of secular and Islamists starting with redoing the education system to conform to the Koran. But more important was the sense of the many fragments of secular life that were tangentially affected by a changing society.

Noble Earth ( set in Tuscany) was a huge disappointment, basically the film recorded the good life for elites in Italy and finally had the previously almost silent female star spout out a political speech that was obviously why the filmmaker made the film. Awkward

This is Home ( Syrian refugees in Baltimore) beautiful documentary about several families who are adjusting to life in Baltimore.

Nona, a film about human trafficking also disappointed me, it seemed to be a series of single shots representing various stages of migration, without a believeable central core. A young woman without a family decides to go North with a stranger who pays her way to the border where he blindfolds her and disappears. She ends up in a brothel from which she runs away. Again as in Noble Earth, the politics emerge at the end with a blond “lawyer”? who goes on in English about all the political issues of human trafficking as she is ostensibly questioning her young victim who understands no English at all. This movie could have been so much better. It is a crucial subject.

The Crime of Monsieur Lange ( 1936 return of Jean Renoir film). Jean Renoir’s socialist era film from the mid 1930s in France, the workers form a cooperative and make a business financially successful when the capitalist exploiter returns. Lots of male exploitation of females.

But the key to the film is its appearance of spontaneity, As one critic, Pascal Mérigeau, puts it

“The tour de force accomplished by Renoir with Lange amounted to giving the illusion of improvisation while structuring chaos — without ever ceasing to be chaos.”

I saw an exhibition of Renoir father and son in Philadelphia. We saw how the impressionism of the father affected the eye of the filmmaker, but we also saw what an acute director he was in all sorts of films (none of them with any politics compared to Lange that dates from the height of the Popular Front in France).

This entry was posted on June 19, 2018 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Bearing Witness to Migration Nightmares

Raoul Deal

As we all follow the horrifying details of the administration policy of forcibly removing children from their parents, I am posting this essay to suggest one way forward, we in the creative community must continue to make visible the nightmares of what is happening to immigrants forced from their homes by violence, gang wars and climate change.

Oscar Magallanes

Prelude

Six years ago, a young woman walked into my office in the Grand Central Building on Pioneer Square. She had seen a big poster on the open door for my just-published book, Art and Politics Now, Cultural Activism in a time of Crisis. She asked me if she could work for me! I explained to her that I was simply a writer and had no employees.

Then she told me her story: she had just been released from the Detention Center in Tacoma. As a young mother she supported herself, her own mother and her young child. She worked in a tech job, and had been making a good salary, when the police stopped her on the road because she had a taillight burned out. But then they checked her status (at that time police were cooperating with ICE) and discovered she was undocumented. They immediately sent her off to the Northwest Detention Center for deportation.

In 2012 she was able to post bond and get out without a monitoring device (which now must be rented for a huge fee and re-charged every day), but they had taken away her driver’s license and other documents. She was on her way to a lawyer down the hall to try to get working papers. At that time I had never heard of the Tacoma Detention Center. She urgently asked me to publicize the terrible conditions there.

Over the next two months, I encouraged her to join me at various immigration events, including a May Day march. For obvious reasons, she did not want to make a speech, but I introduced her to several groups supporting immigrants. Then suddenly she disappeared and I never saw her again. I have no idea what happened to her. I saw her lawyer a few years later and she told me that her clients often disappear.

Part I Exhibitions

But this impressive young woman had planted the seed that has led me to learn about the dreadful conditions at the Northwest Detention Center (NWDC) in Tacoma, to join the resistance there, and to organize art exhibitions about immigration, accompanied by music, poetry, speeches by activist leaders, and community organizers.

I began by acquiring and framing thirty dramatic prints of the Migration Now portfolio published by Justseeds/CultureStrike, both activist printmaking collectives. I have shown these compelling works by nationally known artists six times in venues ranging from the University of Washington School of Social Work to the little known Karshner Museum in Puyallup, Washington. The imagery is as resonant today as when the artists first created it five years ago. No one looking at them needs an art background to understand the issues of immigration ranging from the large economic forces such as drug wars and climate change to the personal challenges and day-to-day fears.

Every artist wrote an explanation of their art so their intentions were clear. For me that clarity is crucial: this is not the time for subtlety. But these prints are eloquent works of art. Even as they address an issue directly, they do so in ways that elevate the subject from a polemic to a poetic invocation.

For example in the work illustrated at the top of the post, Raul Deal declared: “On a daily basis I witness the awful toll that a broken immigration system takes on Latino students, friends, and their extended families. Nobody is untouched.”

Along with that project, I curated three exhibitions. “Migration” at the Columbia City Gallery with three artists, Deborah Faye Lawrence, Tatiana Garmendia, and Cecilia Alvarez.

Tatiana Garmendia Border Crossing,still from video

I reached out to twenty artists in “Liberty Denied: Immigration, Detention, Deportation” at the Museum of Culture and the Environment, Central Washington University .

center Cecilia Alvarez, foreground Christian French INS game, background right Carina del Rosario

“Immigration: Hopes Realized, Dreams Derailed” in Tacoma, Washington at the Spaceworks Gallery. Here is an installation shot including Eduardo Trujillo reciting spoken word at one of the events See this performance video

Andrea Eaton Guadalupe Garcia

Pavel Bahmatov

Eduardo Trujillo

With each exhibition my understanding of the issues increased, along with my horror. The more I learned, the more urgently I wanted other people to understand the situation.

Part II Activism

My education continued with the group “Aid To Immigrants Northwest,” (AIDNW) an organization that provides assistance to recently released detainees, right outside the Detention Center in Tacoma. They hold bi-monthly roundtables with programs on topics not generally covered in the public press. For example, at one meeting that I attended they talked about the fate of children whose parents are detained or deported. Another explained the difficulties of the visitation rights of families, with changing visiting hours and detainees moved to far away facilities. At a third roundtable the discussion focused on the difficulty and high cost of phone service for detainees.

The NWDC, they explained, had 1500 beds, making it the fourth largest detention center in the country. Run by the for-profit corporation GEO, in contract with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), NWDC is one of the biggest moneymakers in the immigration system. GEO pays detainees one dollar a day to do all the work of the Center and requires different color uniforms, blue, orange, red, green, according to their level of “threat,” generating divisiveness among the detainees.

AIDNW provides released detainees basic necessities such as clothing: they have only the clothes on their backs when detained, if they are released in the winter and have been detained in the summer, they will freeze without additional clothes. In addition, AIDNW provides temporary housing and transportation assistance.

Through AIDNW I signed up to be a visitor at the Detention Center. They matched me with a grandmother about my age. Visiting her was like visiting a prison, multiple security layers, and speaking through a partition on a telephone, as though she were a dangerous criminal. She told me of her problems with the diet, high salt, high sugar, making her sick, and raising her cholesterol. She had to wait for weeks for an appointment for medical attention. Even more important though, she had lived in the US for decades, she had a home and family here. Tragicallly, both her daughter and mother had died since she was detained. She longed to be reunited with her grandchildren.

Detainees do not have a right to a lawyer, since lacking papers is a civil offense, they can only get a hearing with a judge. If they are lucky, a volunteer lawyer represents them, but most of them have to defend themselves, even if they don’t speak English. (One elderly detainee described how she couldn’t even read the documents, since they had taken away her glasses.)

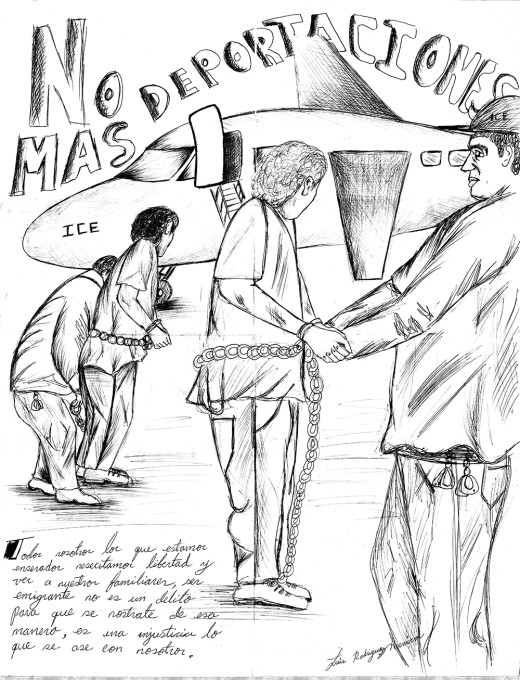

The detainees, like characters in a Kafka novel, live from hearing to hearing, often spending months or even years in the windowless, inhumane facility. Their other choice is to go directly into deportation. The buses wait outside the Northwest Detention Center to take them to the airport to be flown off, at vast expense, to a country they often have not lived in since they were small children. One detainee, Louis Rodriguez Arenival, made this picture of deportation.

The written text in the lower left says: “Todos nosotros los que estamos encerrados necesitamos libertad y ver a nuestros familiares; ser emigrante no es un delito para que se nos trate de esa manera, es una injusticia lo que se hace con nosotros.” The translation is “All of us who are locked up need freedom and to see our relatives; being an emigrant is not a crime, to treat us that way, what is done to us, is an injustice.”

Another current detainee, Pavel Bahmatov, sent art to two of my exhibitions through the intermediary of the Northwest Detention Center Resistance “pen pal” project. Pavel, along with others, alleviated the extreme boredom of the center, which unlike federal prisons has no programming at all, by making art woven from recycled trash such as ramen noodle wrappers. Here is an example of some of his beautiful work. He is originally from Uzbekistan, so there is, to me, definitely a central Asian sensibility in the colors and patterns.

Pavel had a bail hearing with a pro-bono lawyer from the excellent Northwest Immigrant Rights Project, who explained in detail why he deserved to be released. Then the Judge listened to the prosecution declare he was a threat to the community, and denied bail in about thirty seconds. Bahmatov was transferred to a facility in the Dalles, NORCOR, which is actually a county jail. The facility collects daily payments from ICE for the detainees there, without providing even the minimal services of the NWDC. Bahmatov joined a hunger strike there, because there were no other options left to him. Hundreds of local jails across the country are cashing in on the ICE bonanza.

I urgently wanted to find more ways to understand the nightmare of migration policies, so in May 2016 I joined the poet, Raul Sanchez, in organizing a booth before the May Day March. We invited adults and children to write poetry and create artwork in response to the question, hung in a big banner over the booth “How Have Immigration Laws Affected You?/De Que Maniera Le Han Affectado Les Leyes Immigraciones? ”

We were deeply moved by the creativity of those who participated. The drawing illustrated here, by a very young child depicts her mother in Mexico at the bottom right, and herself and her father in the top left, separated by two fences.

In the last five years, I have also joined protests organized by the Northwest Detention Center Resistance (NWDRC). They gather weekly outside the detention center. Here is one of their protests.

The corporation GEO makes enormous profits there through the “volunteer” labor of the detainees, while perpetuating deprivations that are against the law. People who have gone from federal prison to detention often comment on how much worse the conditions are in detention.

The NWDCR protests call attention to the human rights violations, and support hunger strikers, detainees and deportees (sometimes with a cross border telephone call). At one protest, the Vashon-based Backbone Campaign flew a banner that floated over the center reading “Who Would Jesus Deport?”, infuriating the officials inside.

On the Day of the Dead in 2014 Maru Mora Villalpando, a leading Northwest Immigrant Rights activist, dressed up as Calavera Catrina and led a march protesting the conditions in the Center, complete with the GEO House of Horrors ( scaled to the size of a solitary confinement cell) and gravestones marking “families ripped apart” and “orphaned by ICE.”

Villalpando is currently threatened with deportation herself in a nationwide ICE action that targets activist immigration leaders.

Part III Art joins Activism

In the summer of 2017, my activism and art curating came together at Spaceworks Gallery in Tacoma on the project “Immigration: Hopes Realized, Dreams Derailed.” Perhaps because the gallery was located only one mile from the Northwest Detention Center, the exhibition itself, as well as the two evenings of performances in the intimate space, were deeply affecting. The artists, poets and performers included political activists, undocumented immigrants, former detainees, current detainees, DACAs (Delayed Action for Childhood Arrivals), college honors students at University of Washington Tacoma, who and never made art before, self- taught artists, and professional artists.

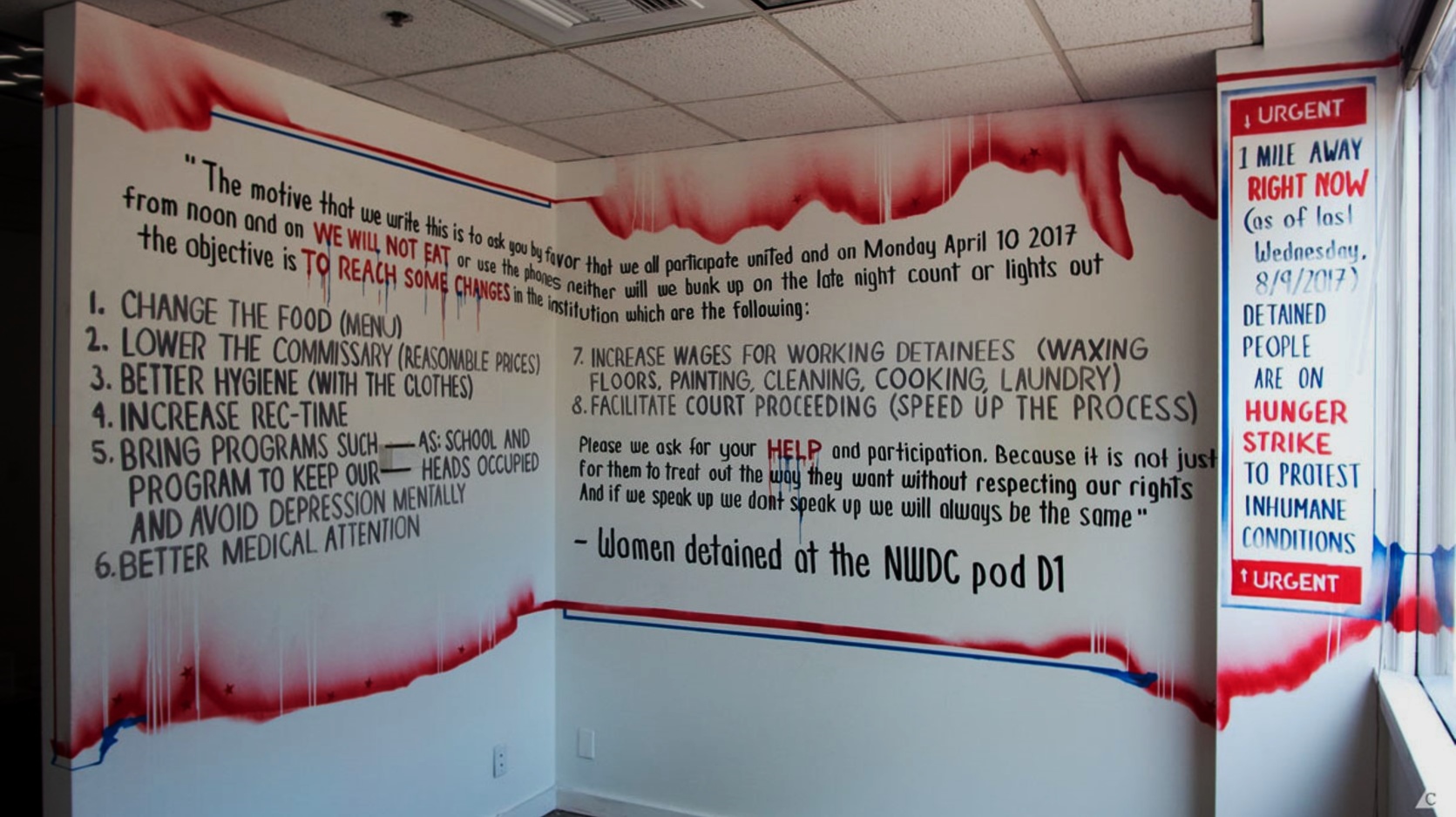

Street muralist David Long created a painting over two walls that listed in bold lettering all the demands of the hunger strikers including improved food, better medical services and hygiene, increased recreation, programming “to keep our heads occupied and avoid depression,” increased wages, and better facilitation of court proceedings.

Spaceworks Gallery is a small community-based space with big windows on the street. People outside stopped to listen to the heartfelt musical performance of former detainee Eduardo Trujillo. He describes himself as “a passionate refugee who seeks a way to bring peace of mind to those incarcerated and or in fear of deportation.” Eduardo brings hope to people through music and spoken word. You can hear him as well as see the exhibition at: https://vimeo.com/226673443

Behind the facts and statistics of immigration and detention, I have learned personal stories of mothers, fathers, children, aunts, uncles, grandmothers and friends who live in fear every time they wake up in the morning, but resolutely go to work, care for their families, and maintain hope. Young people live constricted lives because they lack social security numbers, drivers’ licenses, even library cards. The Delayed Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) has given some immigrants a way forward, but the program is threatened with cancellation and has become a political football for draconian immigration legislation.

At the same time, the deportation of parents makes orphans and/or exiles of thousands of citizen children every year. Hardworking families saving money from two or three minimum wage jobs lose it all to an unsavory lawyer. Savings for a college education goes to enable a deported father to return to his home and family.

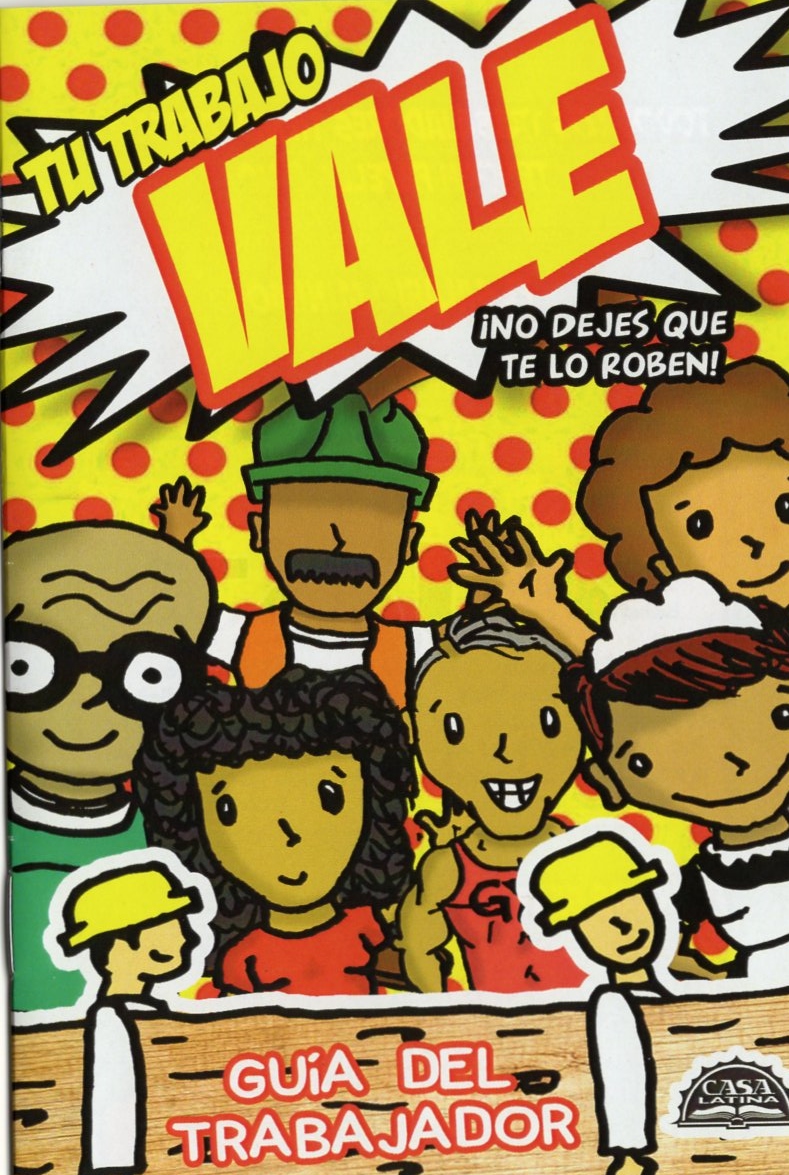

But there are also success stories, stories of resistance, of defiance, of courage. These are even less reported in the media, more frequently stories we don’t hear. I am so thankful that the young woman who stopped in my office six years ago, woke me up to an invisible nightmare that I could play a small part in making visible through art and activism. Above all, I have been profoundly moved at the courage of immigrants as they continue to demand justice, the return of their loved ones, and a means to legal citizenship. Here is a poster from the excellent workers organization Casa Latina demanding an end to wage theft.

This entry was posted on May 10, 2018 and is filed under Uncategorized.

William Kentridge “Triumphs and Laments” in Boston

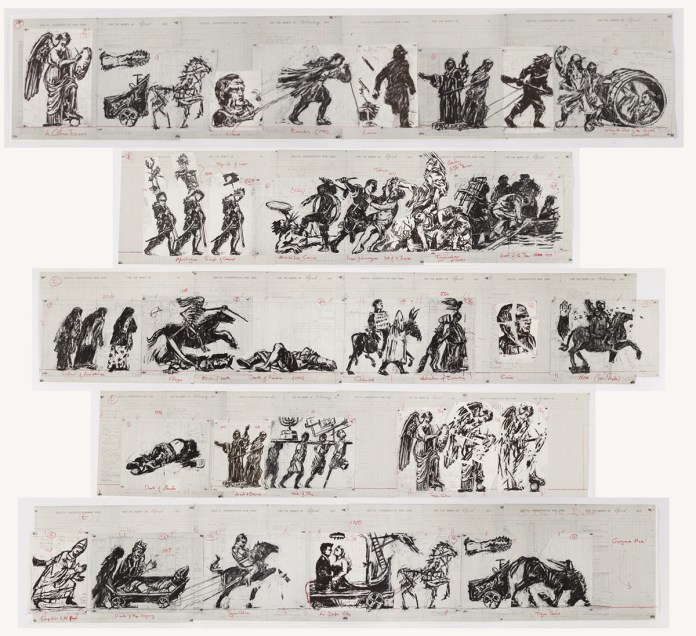

Curator Pam Allara in her exhibition “William Kentridge: Triumphs and Laments” at the Emerson Urban Arts Media Gallery, Emerson College, Boston. The exhibition included seven giant prints (you see two behind her suggesting their scale), steel sculptures on the wall based on huge heads carried in a performance called “Triumphs and Laments,” film clips from the performance which took place on April 21st 2016, and a maquette of the giant “reverse graffiti” frieze in Rome along the Tiber River. This is a sketch of the frieze which Kentridge refers to as “unwinding the Trajan Column”.

Here is Kentridge (on the right) walking beside the wall along the Tiber from “The Triumphs and Laments of William Kentridge” a BBC documentary by Adam Low, 2017. Lone Star Productions.

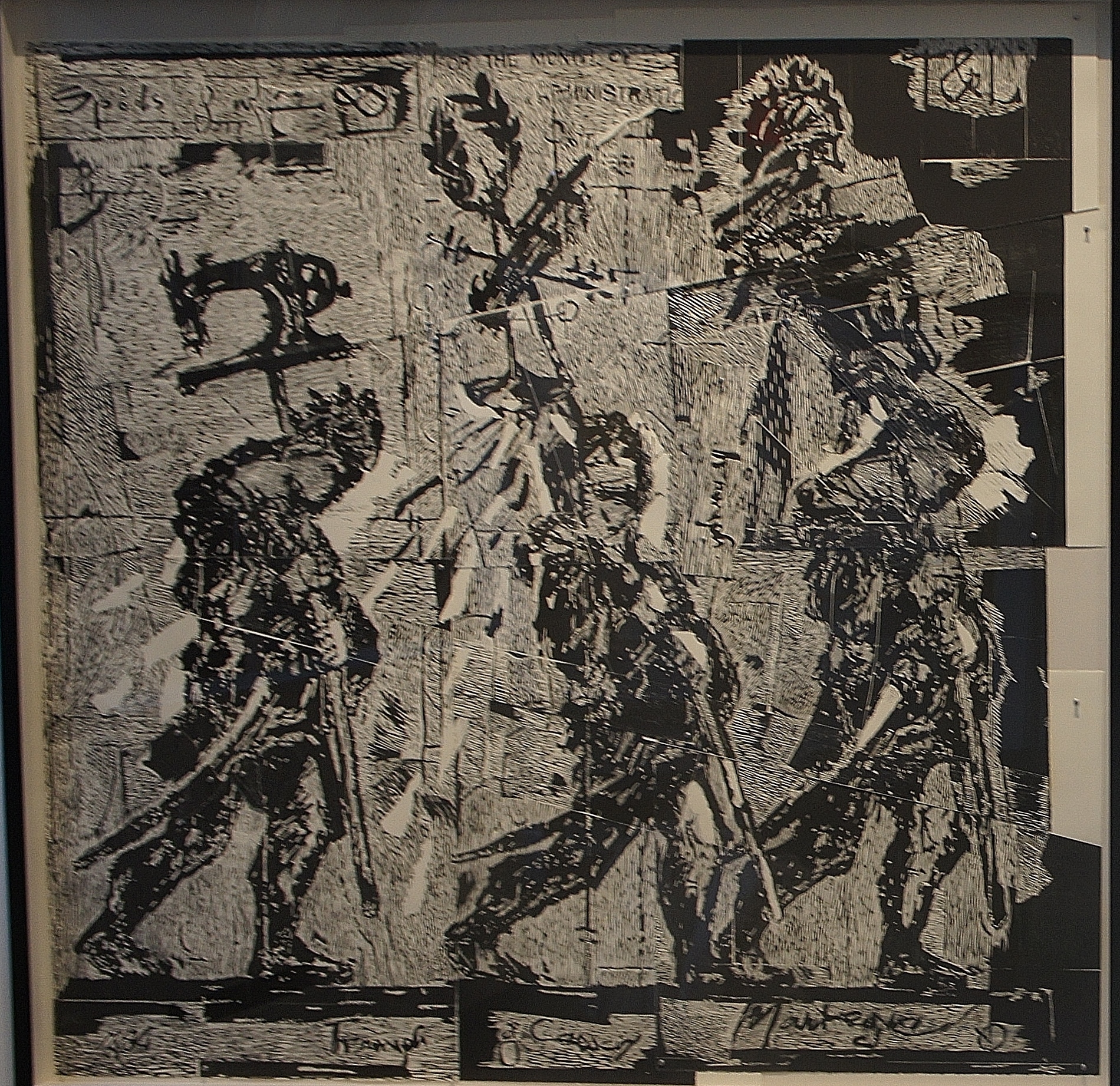

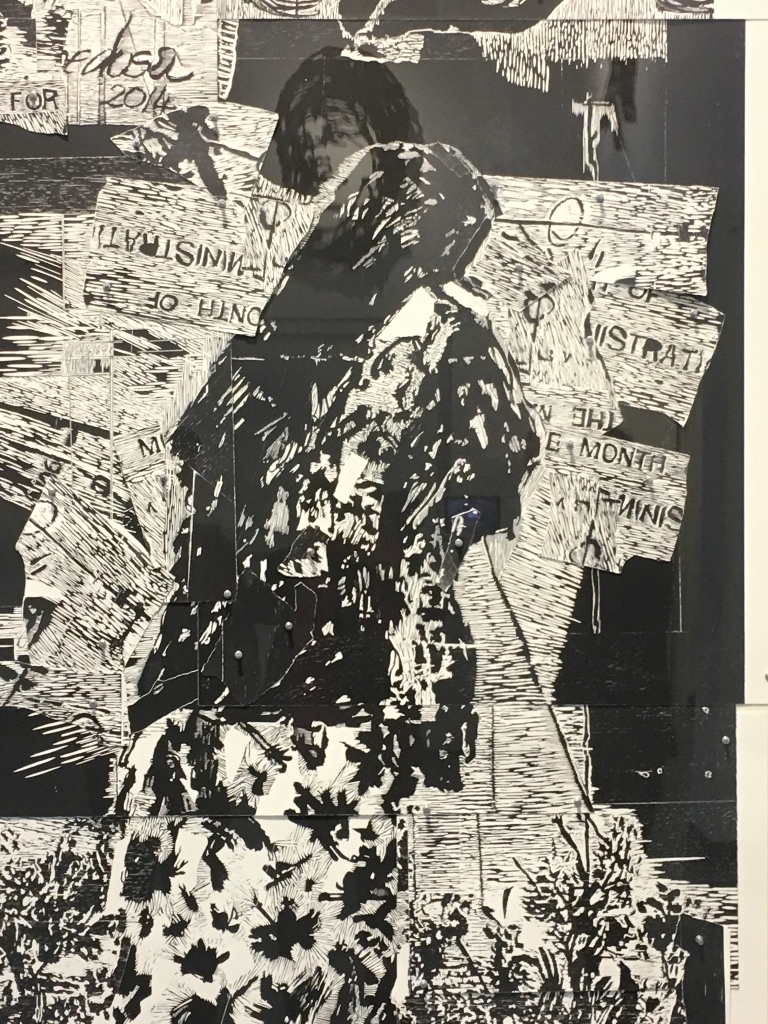

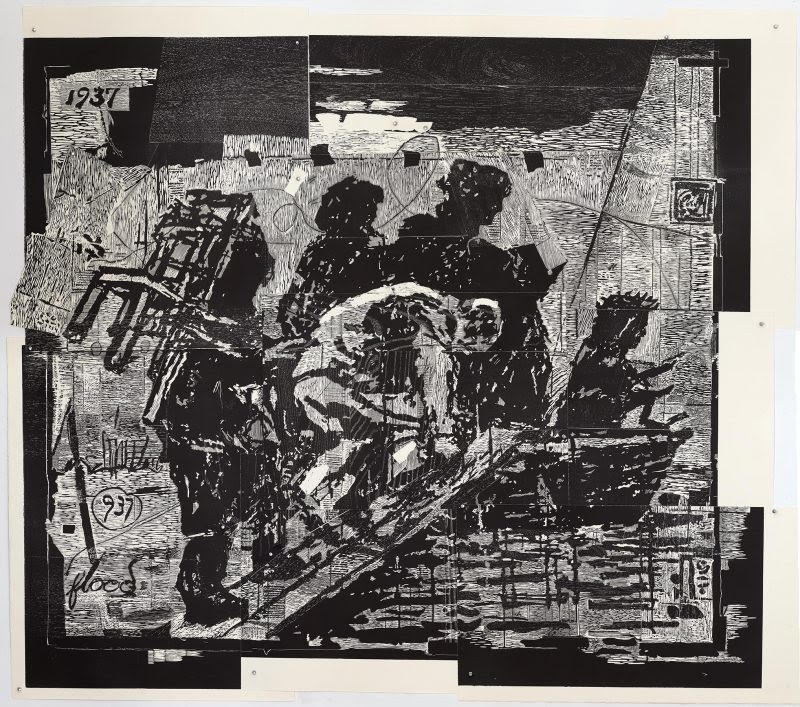

The giant prints themselves are technically spectacular. Here are two of three woodblock prints. They are printed on multiple types of wood, each producing a different texture when cut; the final print is held together with aluminum pins.

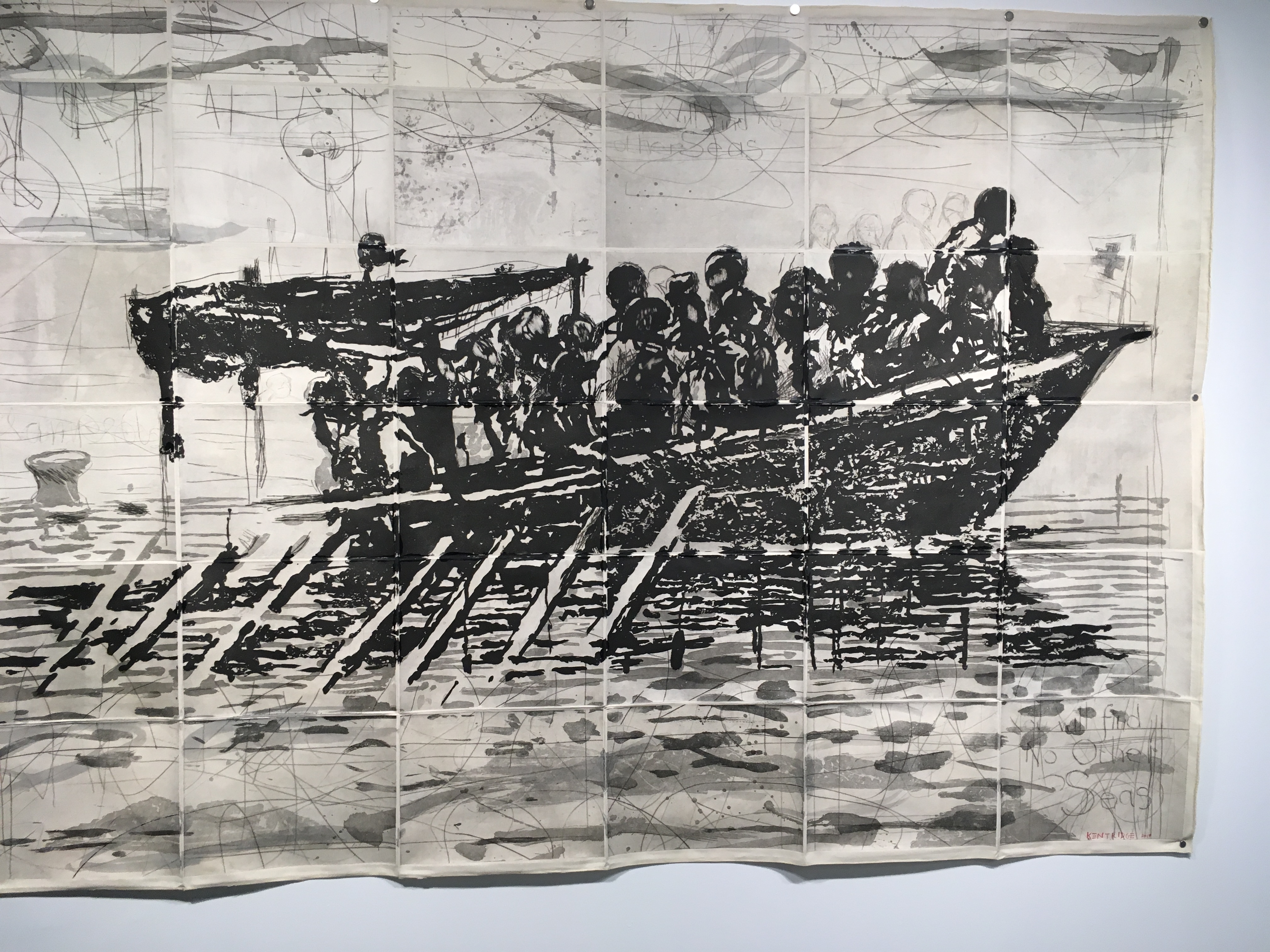

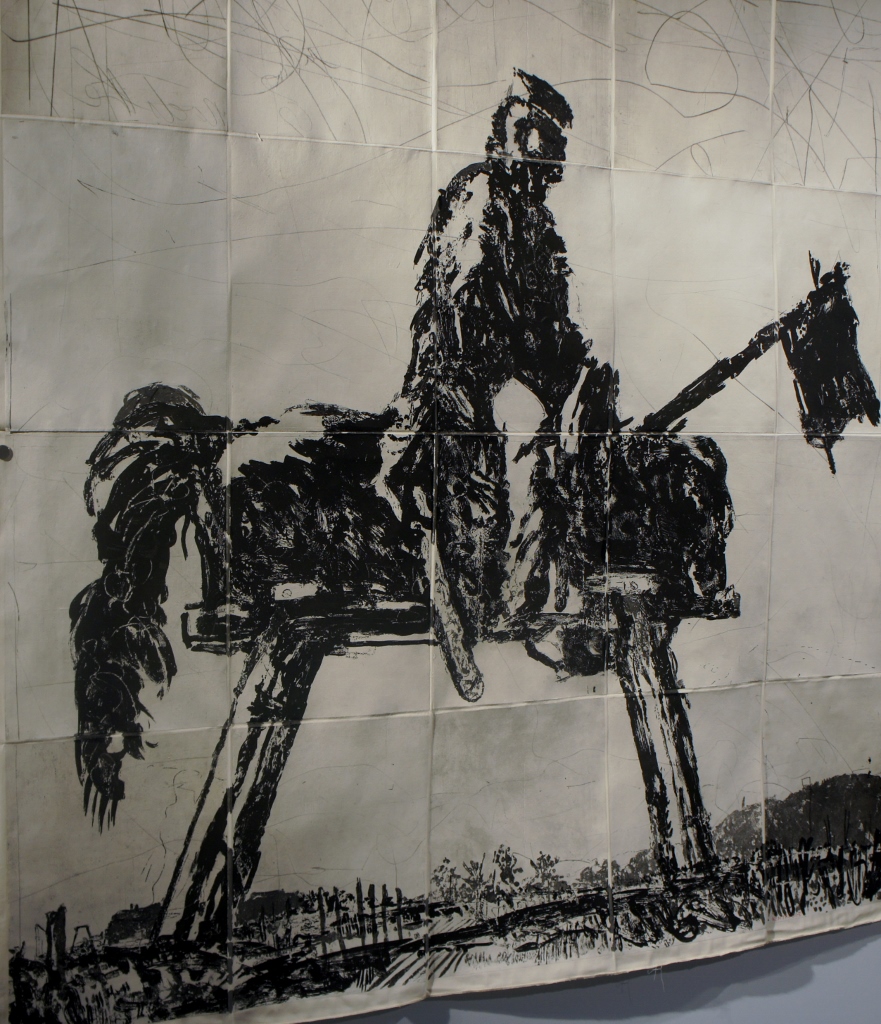

Another four prints came from the Artist Proof Studio in Johannesburg, also landmark printmaking. Lift ground aquatint on handmade paper, they include 20 plates, the print mounted on raw cotton cloth with sketching added by Kentridge.

The seven giant prints draw on the themes of the procession directly: the concept that within the celebrated triumphs or war are laments and tragedies.

So first we have men with booty from a war, based on a work by Mantegna, but they are downtrodden.

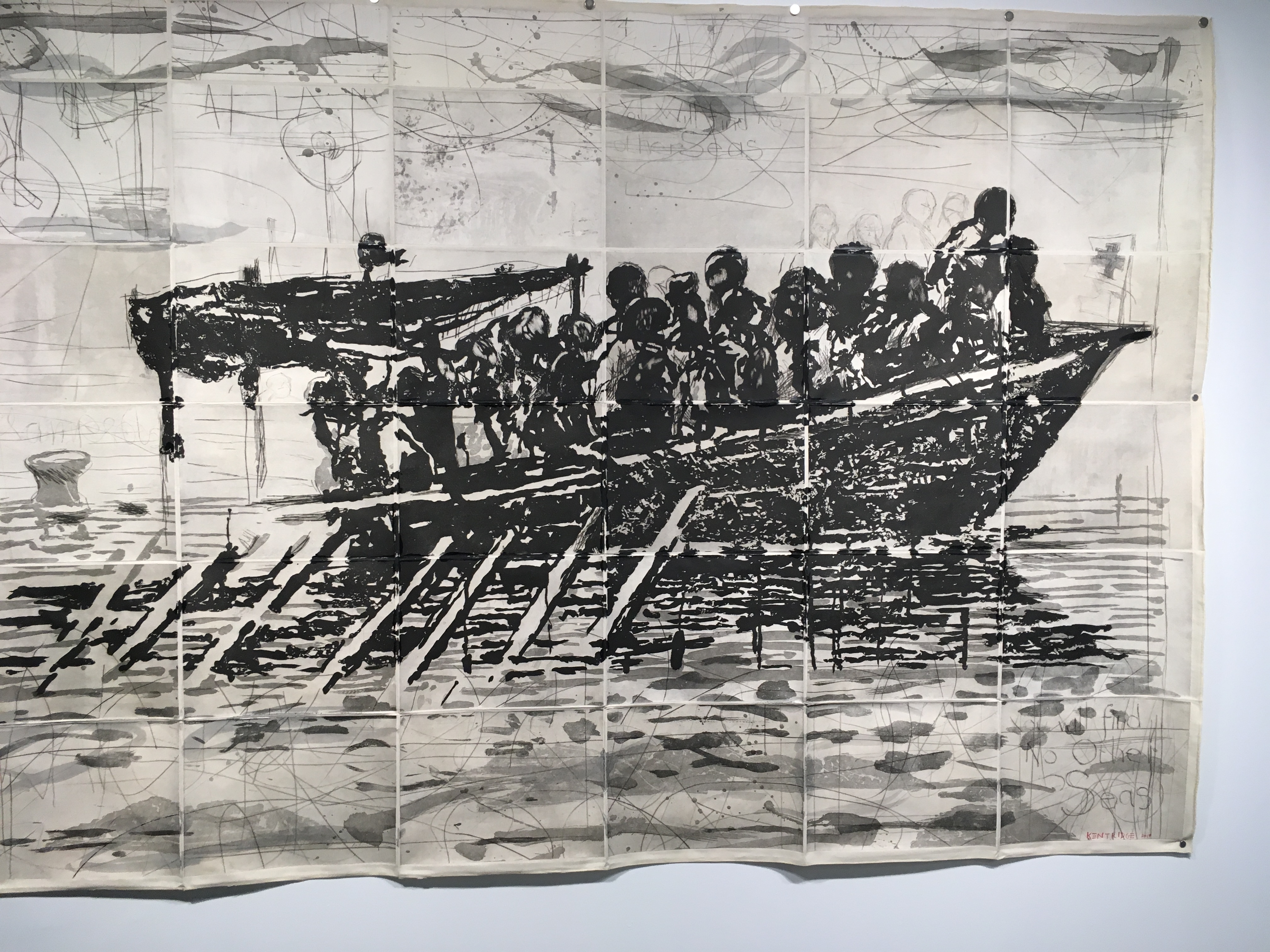

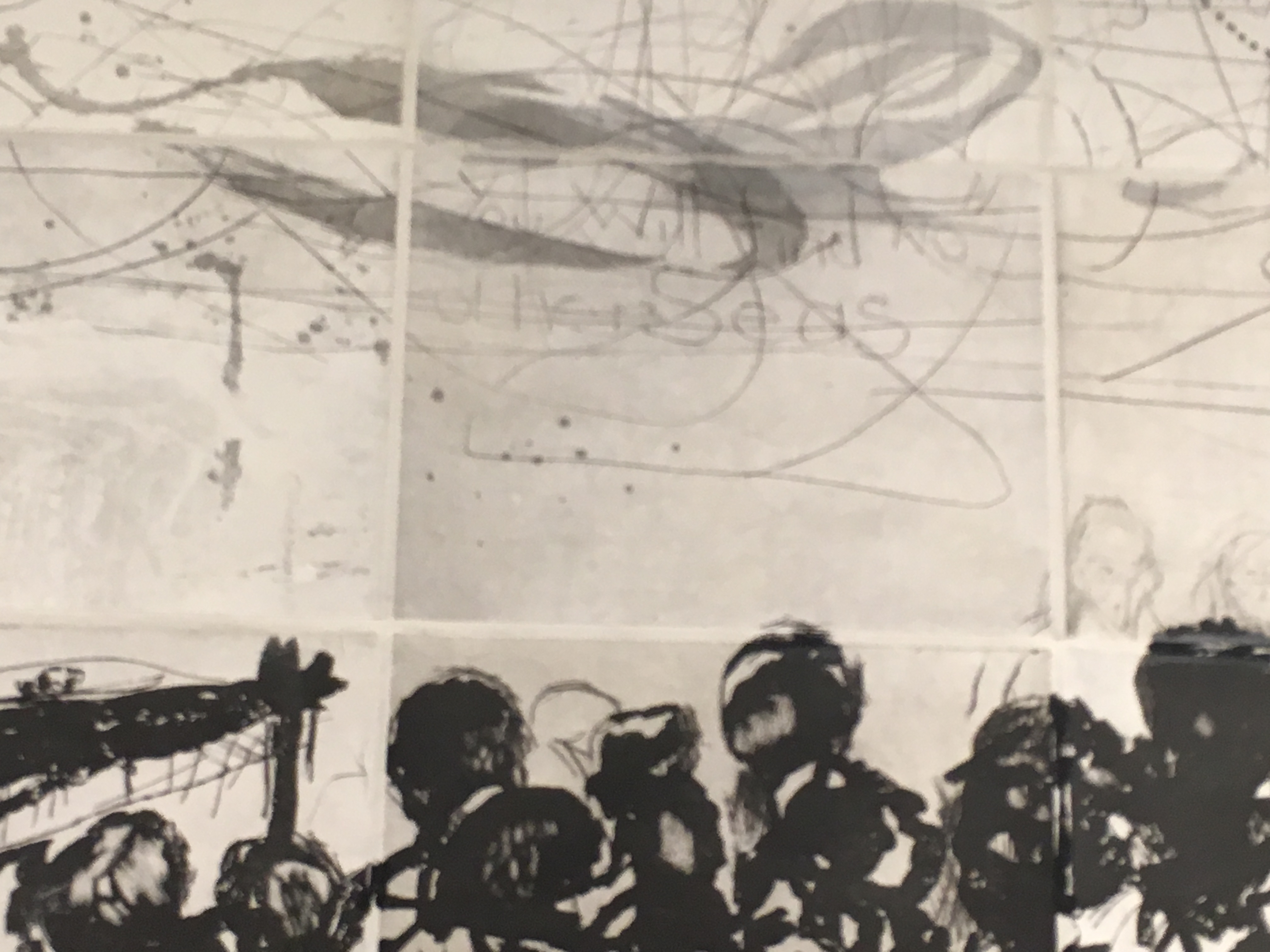

Next is “Lampedusa”, a reference to the contemporary tragedy of migration. In this work a single figure stands on unstable ground. Migration is one aspect of the underside of war and violence. We see it dramatically manifested in the present moment, both on the borders of Europe and the USA. A direct line connects current migrations from Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Central America to migrations of ancient times following the ravages of war.

Next is “Lampedusa”, a reference to the contemporary tragedy of migration. In this work a single figure stands on unstable ground. Migration is one aspect of the underside of war and violence. We see it dramatically manifested in the present moment, both on the borders of Europe and the USA. A direct line connects current migrations from Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Central America to migrations of ancient times following the ravages of war.

Nearby another work called “Flood”, suggests an unstable boat. Lampedusa is the island off of Italy that has received the most boats of refugees from Africa and near which the most refugees have drowned. The central stooped figure seems to echo one of Michelangelo’s anguished sculptures.

It is also the subject of the largest of all the prints, “Refugees, You Will Find No Other Seas”, from the Artist’s Proof Studio, using 36 plates. These desperate migrants crossing from Africa to Italy seem to be both contemporary and ancient. The boat is based on a Roman naumachia, used to fight ersatz battles in the Colosseum!

Here is one photograph of the opening Procession itself.

Procession as a theme is a constant reference point in Kentridge’s work. Usually he creates animations of endless processions of people carrying their lives on their heads in the form of furniture and goods. These processions mark tragedy, oppression, and hopelessness as well as endless perseverance and survival in South Africa, during the era of Apartheid. Kentridge has deep roots in that struggle.

For his giant Tiber frieze, Kentridge rewrote the “triumphs” depicted on Trajan’s column, including the underlying tragedies of every triumph.

Over a period of three years, he created huge figures that make complex references to Roman history, Jewish plunder after the sack of Temple in Jerusalem, the holocaust, (the frieze is at the site of a former Jewish ghetto) , and the disastrous 1937 flood at the site of the frieze itself. These “reverse graffiti” appeared by actually removing the grime of the wall with power washing around stencils of fifty one images (selected from hundreds of possible historical references.) They will gradually disappear over time as the grime returns. To the right of the image above is a blank spot that is labelled ” what we do not remember” in Italian. Much of Kentridge’s work is about how little we remember of history and the distortions of what is remembered.

During the opening event, hundreds of people held giant cut outs of figures, heads and other objects, that were enlarged over the frieze imagery by lighting, suggesting a cyclical, and ever moving procession, accompanied by an orchestra. Here it is on you tube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fqKZ0rZgap4

In the exhibition in Boston, Allara included two clips from the opening performance as well as the maquette of the entire graffiti frieze explaining its complex iconography in an accompanying brochure.

It makes reference to, for example, the founding of Rome in the fratricide of Remus by Romulus.

Also included are references to pathetic dying horses, usually the symbol of victory on many equestrian monuments, here they are referring to the suffering that goes with every victory.

The horses are a major theme in the giant prints. We see Garibaldi the great liberator of Italy on a wooden hobby horse ( apparently the way that equestrian portraits were posed).

On either side of him are “The Triumph of Bacchus” and “Skeletal Horse,” the end of the myths of triumph. Here the horses stand in for the full tragedy and absurdity of war and its consequences. The connection to contemporary processions of people displaced by war is direct and specific in the large prints of “Lampedusa” and “Refugee”.

Skeletal Horse

Triumph of Bacchus

The exhibition “Triumphs and Laments” in Boston, accomplished through Pamela Allara’s perseverance and direct connections to Artist’s Proof Studio, was a rare opportunity to gain new insights into the work of William Kentridge, one of the most important artists working today.

This entry was posted on May 3, 2018 and is filed under "the Kentridge moment", "War and the Body", "War Experience Project" Handspring Puppets, Contemporary Art, Culture and Human rights, Uncategorized.

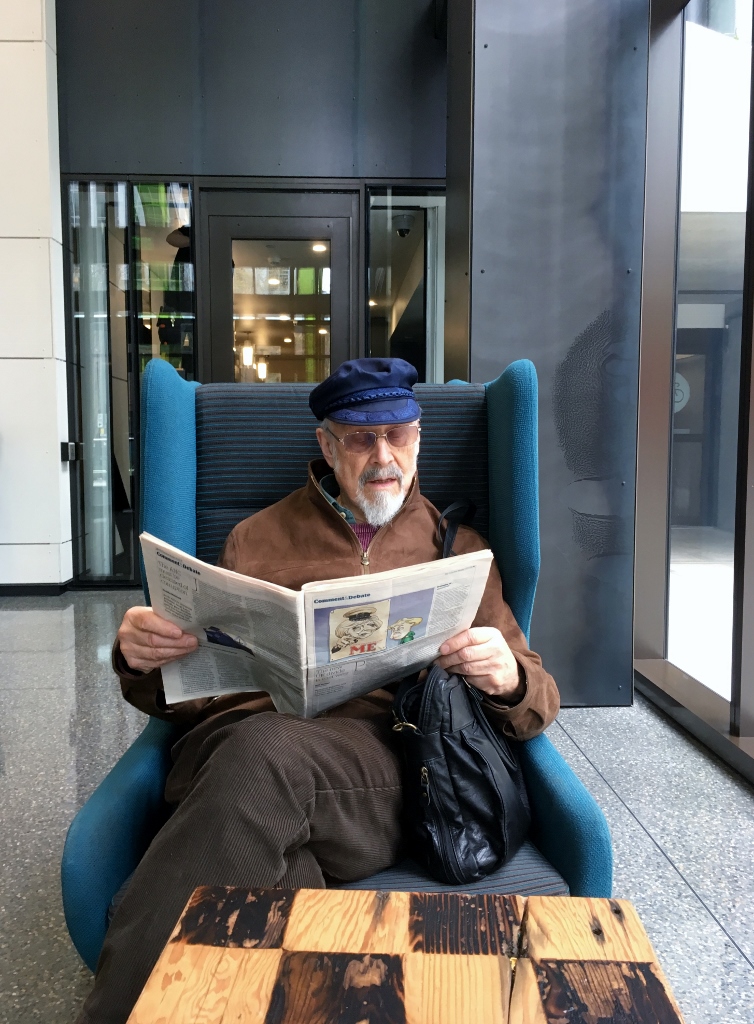

In the belly of the beast

waiting in the comfortable Amazon lobby with soft music playing. Henry is reading The Guardian

This week Henry and I went to visit my dear friend Tim Detweiller who now works at Amazon!! He runs a creative art program there. and being Tim, he is full of ideas and innovation, penetrating the Amazon behemoth with creative classes offered to employees for free.

But first let me set the stage.

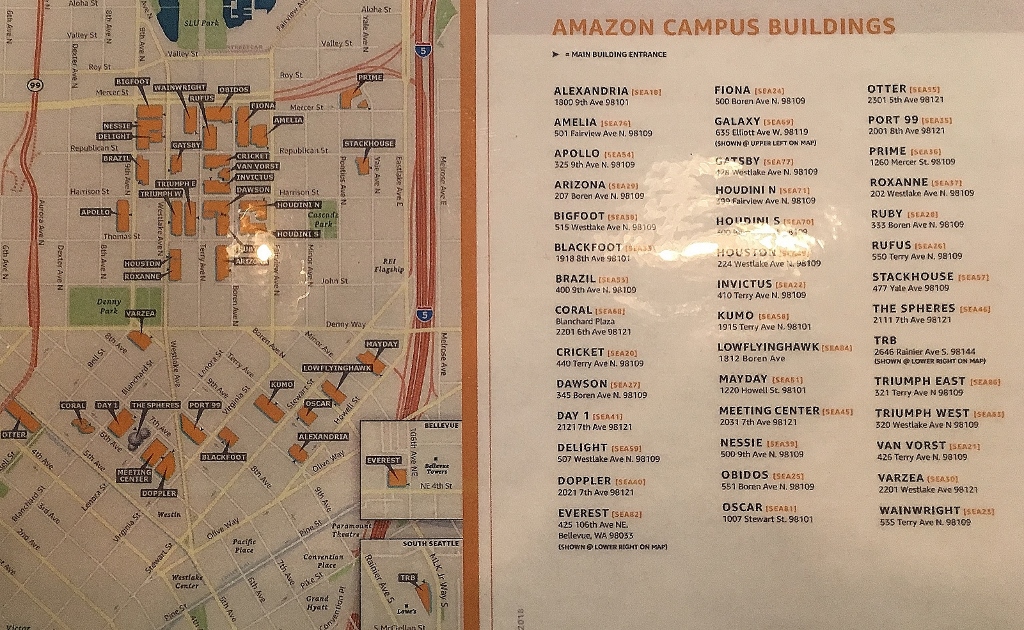

This was a rare opportunity to go inside one of the 42 ( and still building) Amazon buildings on the massive take over of South Lake Union land.

Here is a map of the campus today. We needed an employee with a badge to get through the glass security gates. We went into the Doppler building which is the lowest one on the left in this campus view.

Once inside, we entered a radical new atmosphere for an office building, open floor spaces, a performer playing a guitar, , and a room where nursing mothers can store their milk and nurse their babies.

Soft music played, soft chairs awaited in every direction.

There were food stands with free bananas and outdoor spaces for dogs.

Dogs, Tim explained, were welcome in the offices, providing a means of social interaction. This roof garden had fake hydrants and logs, apparently a secret code saying dog in computer binary code. The art work inside the Doppler was coordinated by the brilliant Sam Stubblefield and it was full of subtleties.

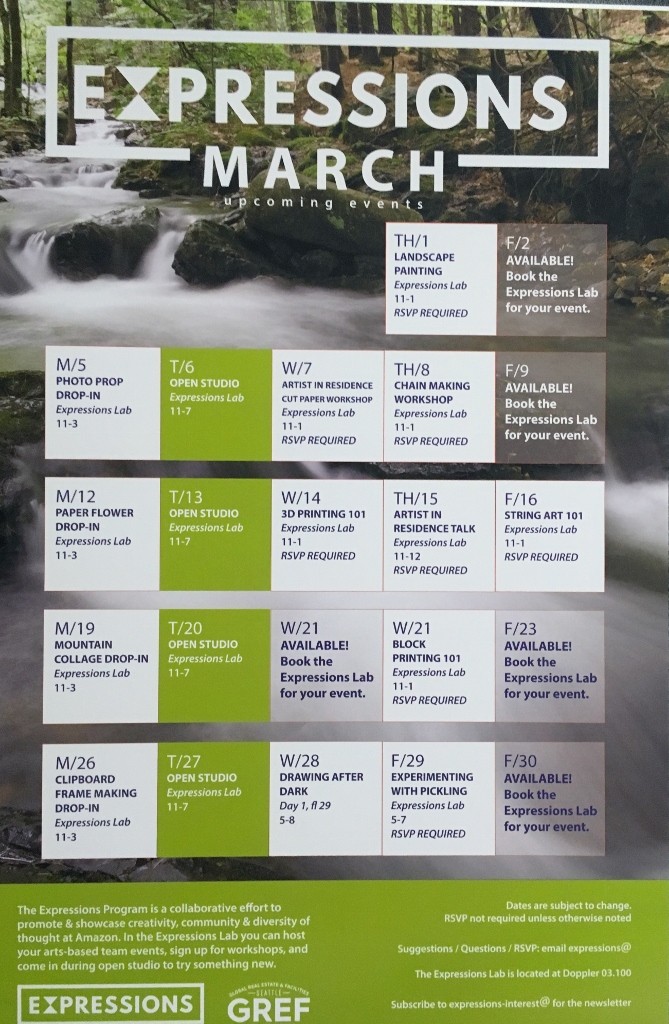

As Tim now defines his cultural program : “The Expressions Program is a collaborative effort to promote and showcase creativity, community and diversity of thought at Amazon.” It is coordinated with a small team of assistants including Joseph Steininger ( left) who is a silkscreen artist.

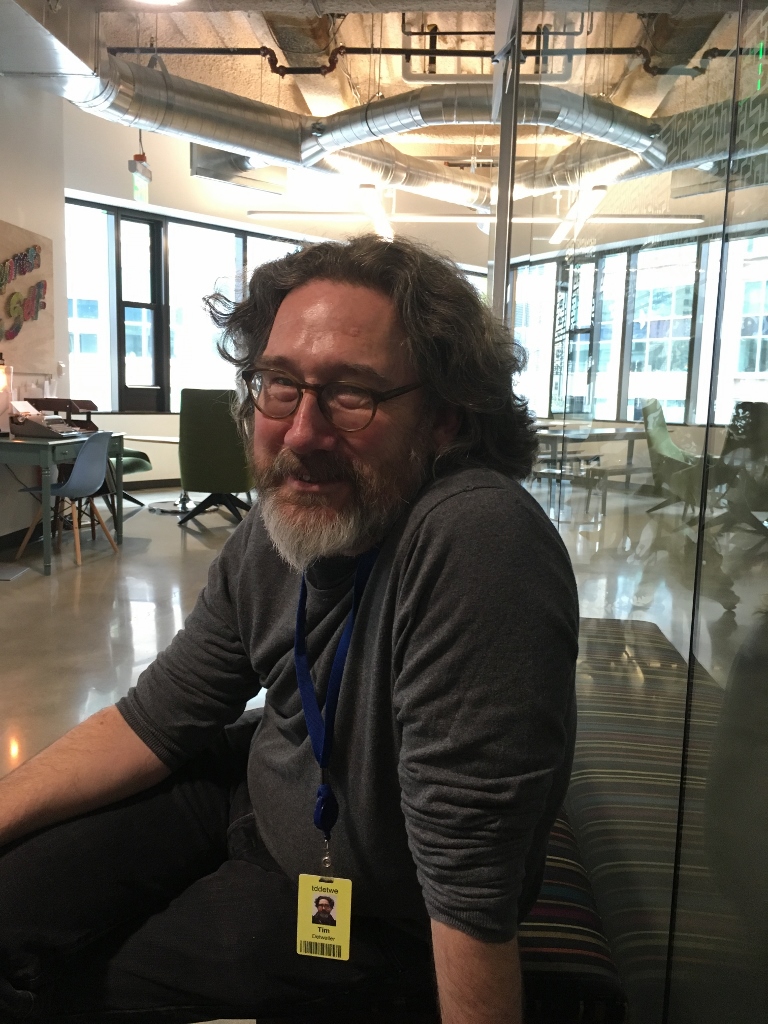

It includes a lab where classes are held, a cart that appears here and there in the building, and a just started artist in residence program. Employees get to take time off to take the classes and they are free. Here is Tim in his lair.

The first artist in residence is Celeste Cooning. Tim took over a room formerly used for ping pong for her studio. Unfortunately there are no public events associated with this residency. But that is true of Amazon as a whole. Privitized, privitized, it it like a country club, very nice for the members who can afford the admission fee.

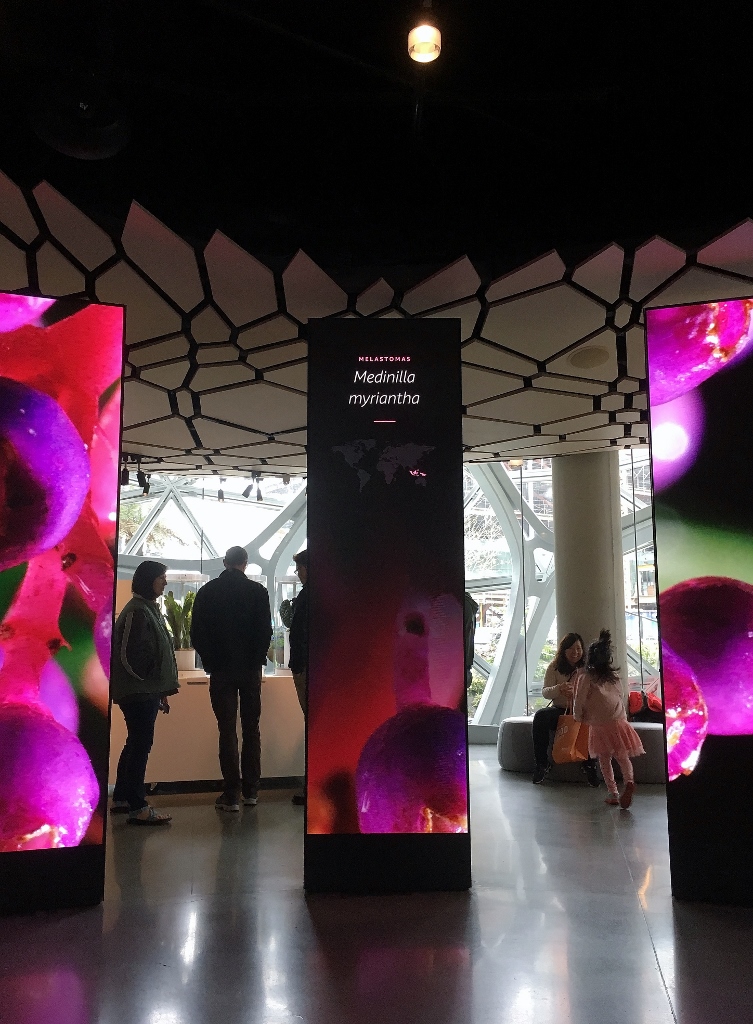

Tim also took us into the spheres, still only available by special permission with an employee.

They were amazing both in terms of engineering and the incredible plant life inside. Apparently there are hundreds of varieties of plants, one sphere has, as the assistant in the small public display area, declared, “old world” and the other has “new world,” a strange out of date classification.

It is coordinated by the chief horticulturalist Ron Galiardo.

with a large team to keep everything at the right temperature and alive (tropical, steamy where we were). There is a 40 year old fig tree in the middle.

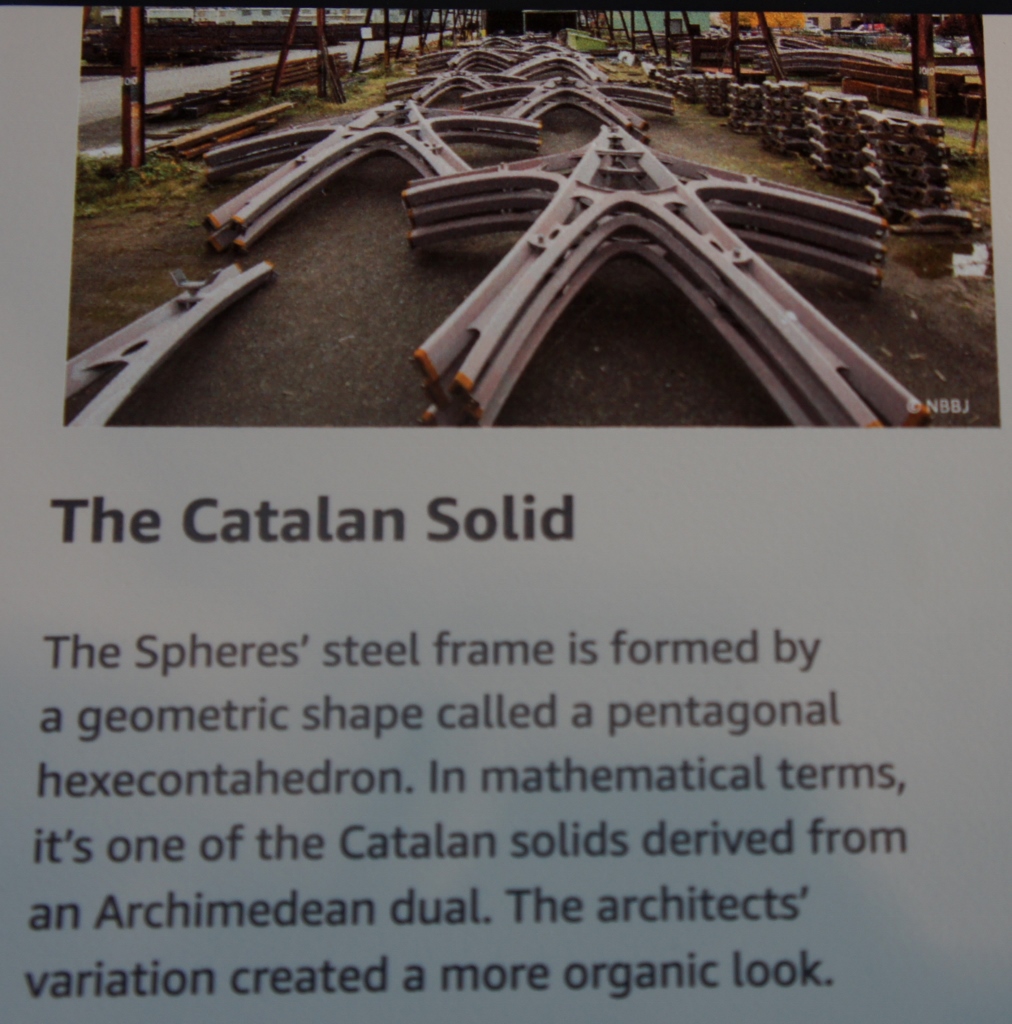

Then we went to a public visitor area on our own where there were giant blow ups of various plants as well as an explanation of the construction of the sphere.

Apparently it is based on the Catalan solid discovered by a Belgian named Maurice Catalan in the nineteenth century.

So what to make of all this

Well. Amazon is certainly trying to make these privileged employees feel comfortable at work. THis building tended to have those affiliated with the more creative side of life, music, film, art.

Of course I have big problems with the extremely contrasting conditions for the non unionized warehouse workers. Hopefully they can at least visit the spheres also. Also creating this monumentally complex environment that is not part of our public sphere makes me uncomfortable. I kept thinking of our beautiful arboretum and Seward Park, how hard those people work to serve ALL of us, not just privileged employees.

Bringing in thousands of plants from various places, apparently they were grown for here, seems a lot of trouble, just to have these weird spheres in our downtown. Their nickname “Bezos Balls” fits them perfectly, they aspire to be iconic like the Space Needle, but of course, this is not part of a fair, or an historic event. Private property can only be a public icon when we can be part of it. As it is, I think it is an intrusion on our city. But then I never buy anything from Amazon ever, since with every purchase, another small business is threatened.

Still, hats off to Tim for bringing creativity and serendipity into Amazon. Hopefully soon he will be able to at least have a public reception for his artist in residence.

I had a corporate week. I also went to Starbucks Annual Stockholders meeting ( I have a few shares in trust for my grandchildren). They are the opposite of Amazon in many respects. They are working to make the community a better place, hiring immigrants, veterans and refugees, giving health care to part time employees, supporting homelessness and being environmentally sensitive. Of course Starbucks is a huge behemoth driving small businesses out also, and neither of these companies allow unions, but at least Starbucks seems to care about the planet. And they seem to have achieved pay equity in some places.

This entry was posted on April 1, 2018 and is filed under Uncategorized.

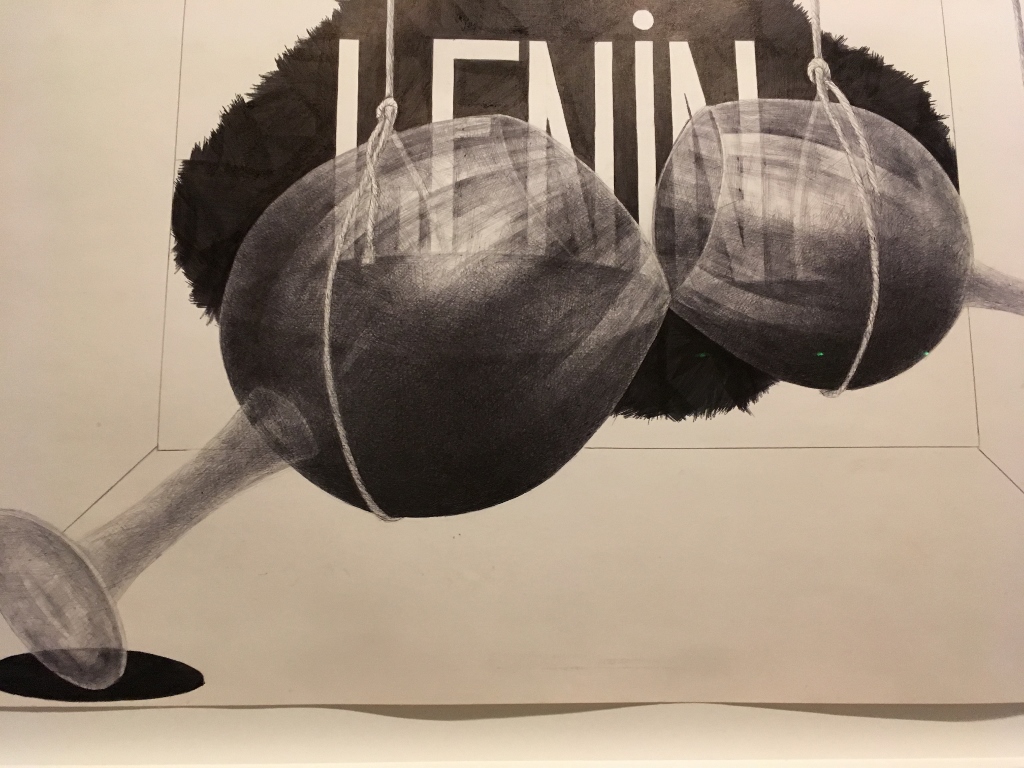

Dmitri Prigov 1940 – 2007 Theater of Revolutionary Action

A brief post. One more celebration of the Russian Revolution in London. Such celebrations seem to absent in the US except among socialists. This fabulous drawing of glasses supspended in nooses in front of a black cloud inscribed with Lenin’s name suggests both where the artist is coming from, as well as where we are today.

Heavens Series with Brooms, 2000

Dmitri Prigov’s exhibition at 22 Calvert in London included some stunning installations. Look closely at this installation. Two upside down brooms hold up a bulging ceiling, placed in a pool of “blood,” the word “Heaven” in Russian in a black cloud coming out of the floor, not where we think of heaven, and an all seeing eye where heaven is supposed to be. It is sardonic, elliptical and provocative. The installation at 22 Calvert is the first time it has been realized. A lot of Prigov’s work are unrealized or “phantom” installations.

He was a poet performance dissident artist in the 1970s, he was institutionalized by authorities in a mental institution in the 1980s. Starting in the 1990s and 2000s he began to create visual art and became well known in Europe.

My knowledge of Russian contemporary art of the 1990s is slight, but what I see here is a direct line to the avant-garde artists who emerged just before and just after the Russian Revolution. Artists like Malevich, Lissitzky, and in his interest in words, Mayakovsky. Boris Groys has written a valuable article distinguishing the lack of purity in Pirov’s messy black splotches compared to, for example, Malevich’s black square. He also connects Prigov to the Dada artists, performance poets.

From the Series Palaces

Prigov represents a despoiled historical world as well. Here the interior of a Russian (Winter?) Palace, perhaps the blood of revolution flowing on the floor in three colors.

Another strange work, based on a pre Revolutionary photograph covered in scotch tape.

In the late 1970s, when Prigov was first performing as part of the underground dissident Russian artists, I had the privilege of taking a course with John Bowlt, then a young professor, now an established and renowned expert on Russian avant garde art.

At that time, Professor Bowlt had just returned from Russia, where he had visited the dissident artists and was able to bring back some of their clandestine work. I still remember when we saw it in class. It was very exciting. Of course the 1970s was long before the great changes in the Soviet Union following the end of the wall in 1989 and the breaking up of the Soviet Union subsequently.

So Prigov’s work of the late 1990s and 2000s that we saw in the exhibition addressed contemporary realities, but he has his roots in that 1970s underground as a performance/poet.

Here is a post Soviet mood, the disintegrating Tower of Babel by Brueghel (using a reproduction), and the all seeing eye.

His emphasis on the all seeing eye, and surveillance, fits with the work of Pussy Riot, discussed in a previous blog. He also, like them, connects to ritual, religion, mysticism, and performance in his work. Eccentric references such as here, are hard to decipher:

The cleaning woman and Angels

The caption reads: “She has bowed her head and does not see what

is happening around her, although, of course, she already knows it all

otherwise would she stand and mutter, “no! no! no!”

What is this about, the hopelessness of cleaning up this mess, perhaps a metaphor for the post-Soviet world. I am not sure.

What is quite clear is that Prigov was something of a megalomaniac. He left thousands and thousands of poems when he died, and lots of unrealized installations.

Fortunately, I went to this exhibition for an evening focusing on feminism and women artists of the 1990s. Katy Deepwell, editor of n. paradoxa, the renowned international feminist journal, spoke about several avant garde women from this era and several artists also spoke. It is clear that the dissident scene in the 1970s was dominated by men, so it was good to see women emerging in the post soviet era. Here is a link to the search page in the magazine, if you type in Russia, you will find many useful articles on Russian women artists in n.paradoxa.

This entry was posted on February 1, 2018 and is filed under Conceptual Art, Feminism, Uncategorized.

Rural England Survives

During our two month stay in the UK, we went on two weekend trips: one to visit my college roommate, whom I haven’t seen in 50 years. The second to Bath and Lyme Regis to visit the grave of Henry’s grandparents and to visit his sister and brother in law near Lyme Regis, a famous seaside community on the South Coast where Mary Anning pioneered the study of fossils in the collapsing cliffs.

My roommate from Mt Holyoke College 1967, Cynthia Parry, lives in an ancient house in Suffolk, a county of East Anglia along the North Sea. Her husband, Martin, is an eminent geographer who has worked on climate change since the 1970s. They are in an idyllic location. We slept in the oldest room, wide oak beams, low ceilings and a little off the horizontal and vertical vertical.

Not far away we visited their local church, St Andrew Ileketshall. The church like many in Suffolk dates back to the Saxon era, is built of flint, and has an unusual round tower. East Anglia has 180 round church towers but they are rare in other parts of England

But most amazing of all are the murals inside, which were painted in the 14th century and rediscovered in 2001. The entire nave was originally covered with paintings, but many were lost or unstable, so only a segment of them have been restored. The result is an extraordinary group of ephemeral drawings, seemingly an underpainting. Of these drawings the most unusual is the Wheel of Fortune. It represents a man pinned to the wheel and others turning it. We see four stages of fortune, pulling up from the left, sitting in majesty on the top, thrown down to the right, underneath the wheel.

There are only two surviving examples in murals, this one and in the Rochester Cathedral form the mid thirteenth century.The subject appears often in manuscripts as Fortune, blind, deaf two faced, giving and taking favors as she pleases, based on a sixth century philosophical text by Boethius. He states though that God’s plan is greater than these random actions

Another mural shows an architectural outline that is more elaborate than existed in any other 12th century wall painting. Cynthia is the church warden of this important church. Rural churches like this one are barely surviving. They have to pay an annual fee to the Church of England to support a visiting minister every three weeks. The church as only about 12 regular attendees. And there are many many of these small rural churches in England like St. Andrews.

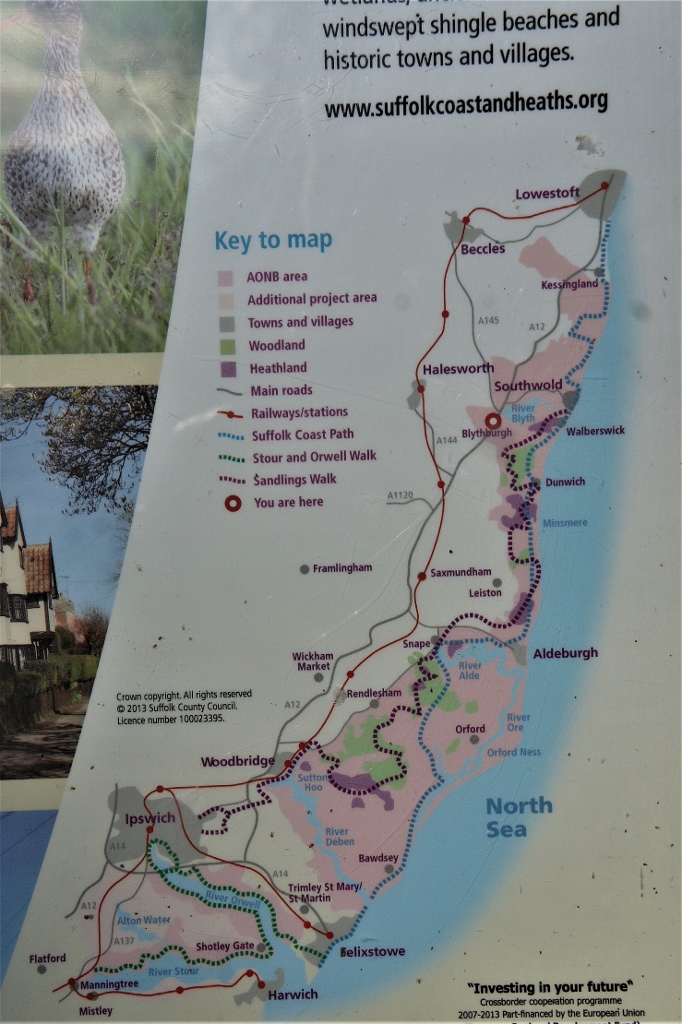

Cynthia and Martin took us on a wonderful tour along the coast ( see map above) We visited a much larger church in Blythburgh entirely made of flint! It had angels carved of wood in the ceiling and other intriguing details like this man ringing a bell. The site shows evidence of burials from the 7th century. The present church is from the fifteenth century.

From there we went to see the Orford Keep from the time of Henry II ( 1133-89). A keep is a fortified tower. It usually is in the middle of a castle ( as a prison). We got there at sunset so did not climb up to the top.

Our last stop with Cynthia and Martin was Snape Maltings, a strange name that means malt used to be made there. Today it is the center of the Benjamin Britten festivals, although no music was going on when we were there. It has ongoing residencies and events. For me the absolute highlight were the sculptures by Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth set against the preserved marsh lands near by.

Part II

We went the next day with Henry’s niece who also lives in Suffolk East Anglia to Ramsholt another even more ancient rural church on the shore. The site of the church dates all the way back to the seventh century although the tower we see today is from the 13th century. You can see that the round tower has been restored. It is unusual because it is buttressed. According to the warden, the bottom was built by Saxons, a little on the rough side, and the rest by the Normans who were skilled with stone building.

Henry’s niece Tig Thomas center and husband Adam, with Henry on cold Suffolk Coast

This entry was posted on January 27, 2018 and is filed under Suffolk East Anglia, Uncategorized.